Harry Sheridan / Alamy

In this article you will learn:

- How to measure temperature in young children

- How to assess whether children are at risk of serious illness

- What to recommend to manage childhood fever

Fever in children is one of the most common clinical symptoms managed by paediatricians and other healthcare providers and is a frequent cause of parenteral concern[1]

. However, serious illness is uncommon in children presenting with fever, with a reported prevalence of serious illness of 0.8% in primary care and 7.2% in secondary care in the UK[2]

. However, despite advances in healthcare, infections remain the leading cause of death in children under the age of five years[3]

.

Fever is defined as an elevation of body temperature above the normal daily variation[2]

. A child is usually regarded as having a fever if his or her temperature is 38â—‹C or above; however, in children aged under five years, a temperature of 37.5â—‹C or above may be considered a fever[4]

. Fever is not an illness; it is a normal physiological response to illness that facilitates and accelerates recovery, reducing the growth and reproduction of bacteria and viruses, enhancing neutrophil production and T-lymphocyte proliferation, aiding the body’s acute phase reaction[5]

.

Fever in young children usually indicates underlying infection. Common conditions include upper respiratory tract infections, flu, ear infections, tonsillitis, urinary tract infections, chicken pox, or whooping cough.

Other reasons for a raised temperature in a child include teething or vaccinations. Parents and carers should be reassured that fever and a local reaction (e.g. pain, swelling and redness) are normal reactions to vaccination and are not harmful.

Assessment

Fever in young children can be a diagnostic challenge because it is often difficult to identify the cause. In most cases, the illness is caused by a self-limiting viral infection. However, fever may also be the presenting feature of serious bacterial infections such as meningitis or pneumonia[3]

.

Routine assessment of a child with fever in primary care should include measurement of temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate and capillary refill time. The parent or carer should also be asked about the child’s history, including recent use of antibiotics, recent vaccinations and vaccination history, recent travel, recent exposure to sick individuals, or previous illness and onset and duration of fever.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recognises that the scope of practice for the majority of non-medical practitioners, such as pharmacists, does not include the physical examination of a young child and therefore assessment will largely be an interpretation of symptoms rather than physical signs[3]

.

Body temperature can be measured in the mouth, ear, axilla (armpit), rectum or on the forehead. Although the oral and rectal sites give the most accurate measurements of core temperature, they are not recommended in children younger than five years of age because of concerns about their safety (e.g. causing bowel perforation or the child biting the thermometer)[6]

. Measurement of temperature using forehead thermometers is also not recommended as it has been shown to be inaccurate, providing a measure of skin temperature rather than core temperature[6]

. The updated NICE guidance on feverish illness in children recommends:

- In children less than four weeks of age, measurement of temperature should be performed using an electronic thermometer in the axilla;

- In children aged four weeks to five years of age, measurement of temperature should be performed using either an electronic thermometer or a chemical dot thermometer in the axilla, or an infra-red tympanic thermometer;

- In children over five years of age, measurement of temperature should be performed using either an electronic thermometer or a chemical dot thermometer in the axilla or mouth, or an infra-red tympanic thermometer[3]

.

Digital thermometers give rapid measurements and are inexpensive. They can be used to measure temperatures from either the axilla or the mouth. Tympanic thermometers can be used to measure temperatures from the ear; however the reading may not be accurate if the thermometer is not correctly placed, or if there is a large amount of wax in the ear.

When to refer

Pharmacists should be aware of the signs and symptoms of meningitis. These include nausea and vomiting, non-blanching rash, neck stiffness, bulging fontanelle, decreased level of consciousness, or seizures. Children presenting with any of these symptoms should be taken directly to hospital. Children with nausea and vomiting who are unable to hold down fluids should be referred to a GP on account of the risk of dehydration. NICE also recommends that immediate transfer to hospital should be arranged for any child with immediately life-threatening features (e.g. compromised airway, breathing, or circulation, or reduced level of consciousness)[3]

.

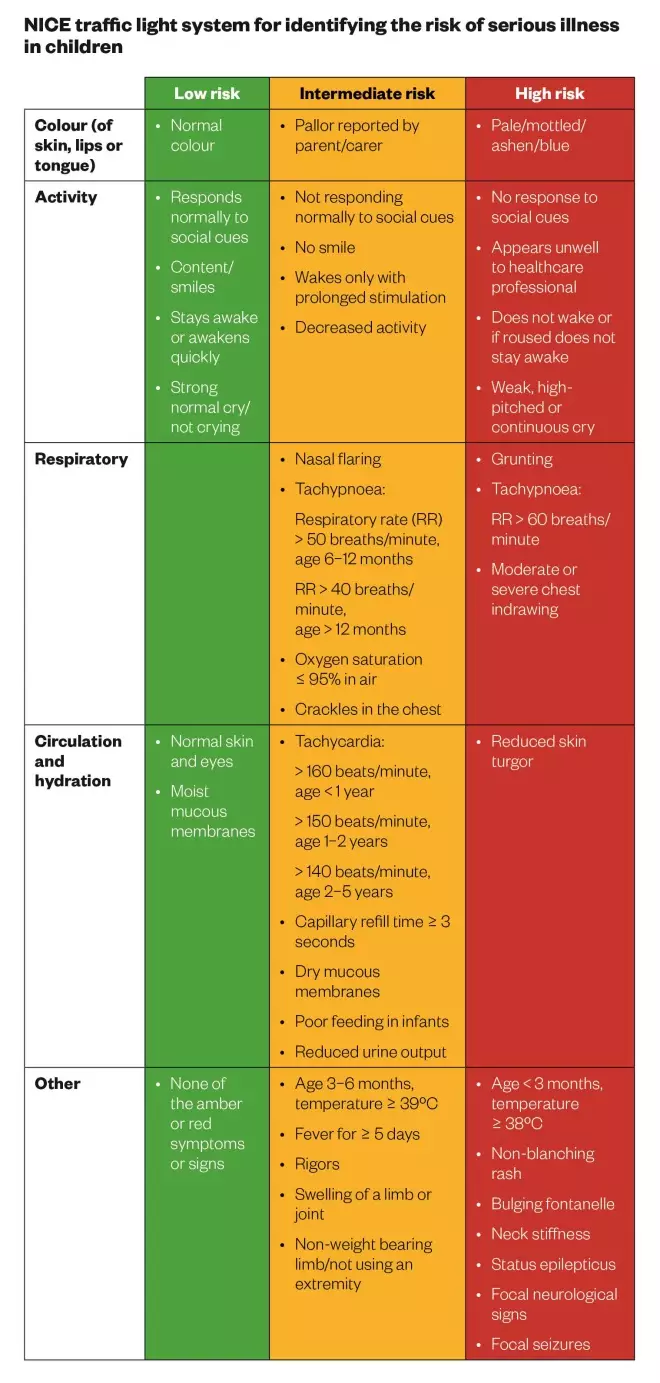

Source: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Feverish illness in children [3]

If there are no immediately life-threatening features, the NICE ‘traffic light’ system should be used for identifying the risk of serious illness in children younger than five years of age (see ‘NICE traffic light system for identifying the risk of serious illness in children’). The purpose of the system is to assist clinicians in identifying those children who may have serious infection in a timely manner. The NICE recommendations are based on systematic review of the best available evidence and cost-effectiveness. When minimal evidence is available, recommendations are based on the guideline development group’s clinical experience and opinion of what constitutes good practice. While the NICE ‘traffic light’ system applies to children aged under five years, NICE considers it reasonable to extend the recommendations to older children[7]

.

The management of children with fever should be directed by the level of risk. If there is any doubt regarding risk, the child should be referred to a GP.

Red symptoms or signs mean the child is at high risk of serious illness and should be referred directly to hospital for urgent assessment (within two hours). This includes all babies less than three months of age with fever of 38â—‹C or above.

Amber symptoms or signs and no red symptoms mean the child is at intermediate risk of serious illness. These children should either be referred to hospital, or can be treated at home as long as one or more of the following steps are followed:

- The parent or carer are given verbal or written information on warning symptoms;

- Further follow-up is arranged;

- Arrangements are made with other healthcare professionals to provide direct access if further assessment is required (e.g. to the GP or directly to hospital, based on clinical judgment).

Green symptoms or signs

and no amber or red symptoms mean the child is at low risk of serious illness. These children can usually be managed at home, and pare

nts or carers should be given appropriate advice about when to seek further medical advice (e.g. if more serious symp

toms develop).

Treatment

Parents and carers are frequently concerned with the need to maintain a ‘normal’ temperature in children with fever[1],[2]

. However, NICE recommends that antipyretic agents should not be used with the sole aim of reducing body temperature in children with fever, as there is no evidence that they prevent febrile seizures[3]

.

Pharmacists should advise parents that paracetamol alone or ibuprofen alone may be used if the child appears to be distressed or in pain; combination use of paracetamol and ibuprofen is not recommended, since the clinical benefit is considered to be too small, although parents and carers can be advised to switch to the alternative medicine if the child’s distress is not alleviated[7]

.

Paracetamol and ibuprofen, when used at appropriate doses, are generally regarded as safe and effective agents for short term use in children. However, as with all drugs, there is the potential for toxicity caused by unintended inappropriate dosing, and data show up to 50% of parents and carers administer incorrect doses of paracetamol and ibuprofen[8]

. Therefore, parents and carers should be advised on measurement and administration of the correct dose, and the importance of not exceeding the maximum daily dose (see ‘Oral doses of paracetamol and ibuprofen in children’). They should also be counselled on appropriate measuring devices (e.g. spoons or syringes), recognising other products that may also contain paracetamol or ibuprofen, and keeping medicines out of reach of children.

Ibuprofen is contraindicated in children with renal, hepatic, or cardiac impairment, any risk factors for gastric ulceration or bleeding, hypersensitivity to ibuprofen or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or asthma that has previously been precipitated by an NSAID.

Additional advice for parents and carers managing a child’s fever at home should include ensuring adequate hydration, avoiding tepid sponging, since this can cause vasoconstriction and shivering, and ensuring suitable clothing so the child is neither too hot, nor too cold[9]

. Babies can continue to breastfeed during feverish illness.

Oral doses of paracetamol and ibuprofen in children

| Paracetamol | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age of child | Dose | Maximum daily dose |

| *For OTC products, parents and carers should be advised to follow instructions on the bottle. | ||

1 to 3 months | 30-60mg every 8 hours | 60mg/kg in divided doses |

3 to 6 months | 60mg every 4-6 hours | 4 doses in 24 hours |

6 months to 2 years | 120mg every 4-6 hours | 4 doses in 24 hours |

2 to 4 years | 180mg every 4-6 hours | 4 doses in 24 hours |

4 to 6 years | 240mg every 4-6 hours | 4 doses in 24 hours |

6 to 8 years | 240-250mg every 4-6 hours | 4 doses in 24 hours |

8 to 10 years | 360-375mg every 4-6 hours | 4 doses in 24 hours |

480-500mg every 4-6 hours | 4 doses in 24 hours | |

| Ibuprofen | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age of child | Dose | Maximum daily dose |

*For OTC products, parents and carers should be advised to follow instructions on the bottle. Source: British National Formulary for Children | ||

1 to 3 months | 5mg/kg three times daily | |

3 to 6 months | 50mg three times daily | 30mg/kg daily in 3-4 divided doses |

6 months to 1 year | 50mg three to four times daily | 30mg/kg daily in 3-4 divided doses |

1 to 4 years | 100mg three times daily | 30mg/kg daily in 3-4 divided doses |

4 to 7 years | 150mg three times daily | 30mg/kg daily in 3-4 divided doses |

7 to 10 years | 200mg three times daily | 30mg/kg (max 2.4g) daily in 3-4 divided doses |

10 to 12 years | 300mg three times daily | 30mg/kg (max 2.4g) daily in 3-4 divided doses |

Case Study:

Callum McTavish, a four-year-old boy, is brought to the community pharmacy by his mother who is very concerned. Callum has had a high temperature and been irritable for the past 24 hours. The mother explains she has given two doses of paracetamol, as directed on the bottle, which has not reduced the fever.

The mother explains that she has been monitoring Callum’s temperature using a digital thermometer to measure readings from the axilla and she explains that the readings have been consistently above 38

â—‹C for the past 24 hours. Callum does not have any amber or red signs or symptoms according to the NICE traffic light system and has not been vomiting.

How should Callum be managed?

Referral to a doctor is not necessary at present. You should advise Callum’s mother to ensure he remains well hydrated and to continue to monitor for fever, and to check on him throughout the night. Callum’s mother should also be advised that, if there is no improvement within the next 48 hours, she should seek further medical advice and can contact the NHS 111 non-emergency contact number if she is concerned. Callum can continue taking paracetamol if he appears to be distressed or in pain.

Faye Chappell is Pharmacist Paediatric Infectious Diseases, Evelina London Children’s Hospital.

References

[1] Sullivan JE & Farrar HC; the Section on Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Committee on Drugs. Fever and Antipyretic Use in Children. Pediatrics 2011;127(3):580–587.

[2] Fields E, Chard J, Murphy MS et al. Assessment and initial management of feverish illness in children younger than five years: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 2013;346(2866).

[3] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Feverish illness in children: assessment and initial management in children younger than five years, 2013.

[4] National Health Service (NHS) Choices. Fever in children. Available at: www.nhs.uk/conditions/feverchildren/Pages/Introduction.aspx (accessed August 2015).

[5] Adam HM. Fever and host responses. Pediatr Rev 1996;17(9):330–331.

[6] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Feverish children — risk assessment, 2013.

[7] National Institute for Healt h and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Feverish children — management, 2013.

[8] Li SF, Lacher B & Crain EF. Acetaminophen and ibuprofen dosing by parents. Pediatr Emerg Care 2000;16(6):394–397.

[9] Axelrod P. External Cooling in the Management of Fever. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31(5):224–229.