CAIA IMAGE/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, individuals should be able to:

- Recognise the signs and symptoms of asthma in children and young people;

- Understand the pathophysiology and diagnosis of asthma in children and young people;

- Know how pharmacists can support children and young people and their families with asthma.

Introduction

Asthma is defined clinically as variable wheeze, breathlessness, chest tightness and sometimes excessive cough[1]. There are different ‘asthmas’ (see pathophysiology) variably associated with airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness, as well as episodes of airflow obstruction from oedema, bronchospasm and increased mucous production[2].

It is the most common long-term condition in children and young people aged 6–17 years in the UK, with 1.1 million children receiving treatment and 1 in 11 children and young people living with asthma[3,4].

The UK has the highest asthma mortality rates compared with other countries in Europe and asthma is one of the top ten causes of emergency hospital admissions for children and young people in the UK[5]. There are several reasons why this may be the case, including erroneous diagnosis and poor adherence to guidelines by healthcare providers. Asthma is often trivialised as a condition and it is essential to reiterate to patients, their families and/or carers, and healthcare professionals that it is a potentially fatal disease[6].

This article is the first in a two-part series and focuses on asthma in children and young people. It provides an overview of the condition, diagnosis and the role pharmacy can play in supporting patients and their families. The second article will focus on the pharmacological management of asthma in children and young people.

Pathophysiology

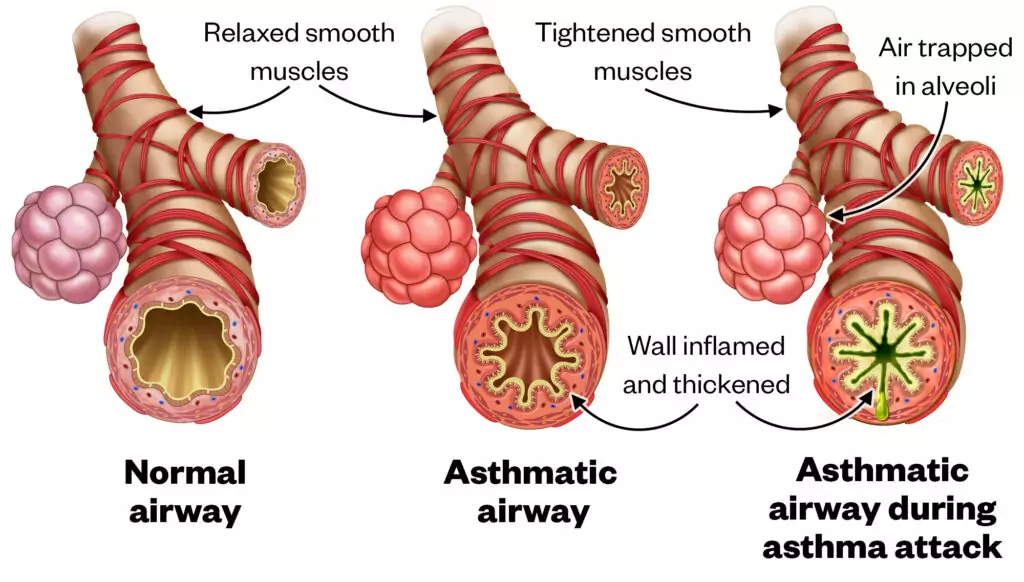

The pathophysiology of asthma involves airway inflammation, airway hyperresponsiveness, the release of chemicals that cause bronchoconstriction. If uncontrolled, asthma can lead to increased mucous production, which can cause mucous plugging (see Figure 1).

Shutterstock.com/The Pharmaceutical Journal

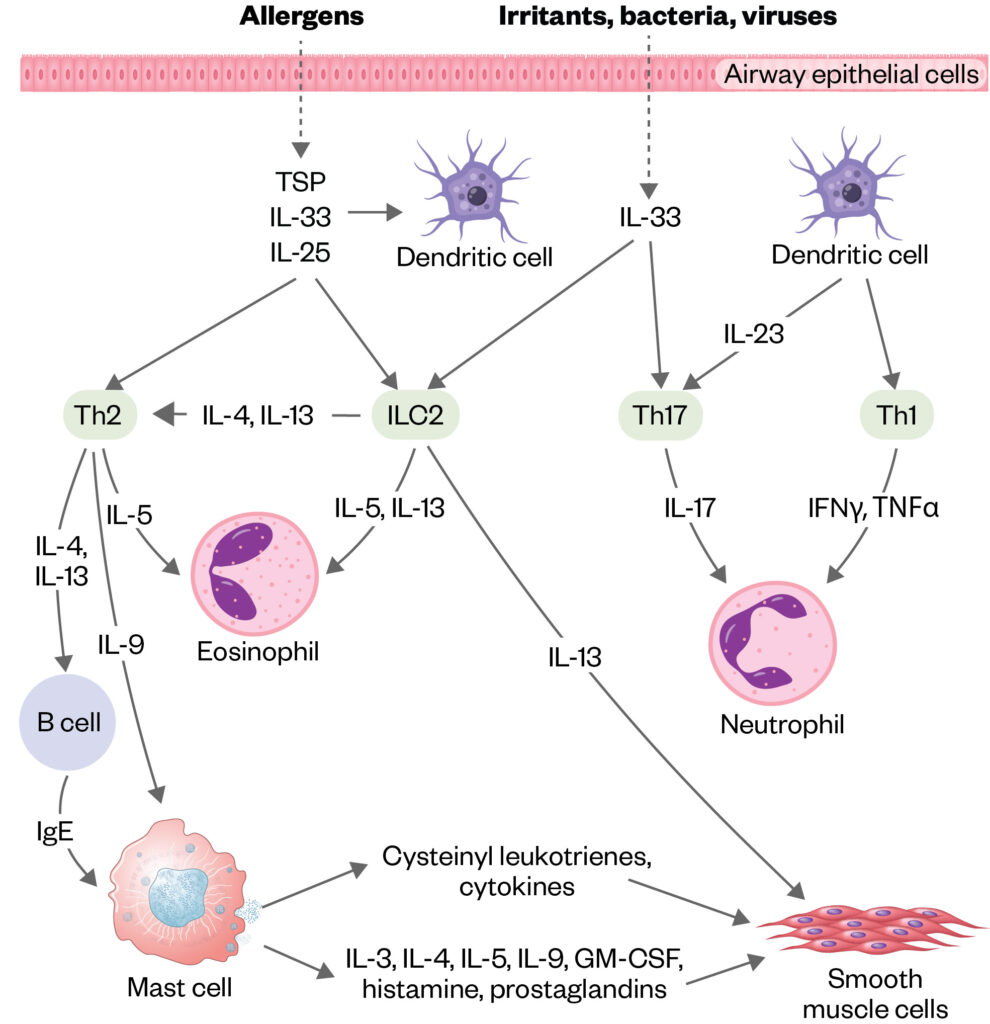

Asthma is a heterogenous condition and can be differentiated into phenotypes and endotypes that can aid diagnosis and targeted treatment[7]. Phenotypes are determined by interactions between an individual’s genotype and environmental factors[8]. Phenotypes are typically defined as eosinophilic (i.e. a higher than normal level of eosinophils) or non-eosinophilic[7,8].

Endotypes are distinct subgroups at a cellular and molecular level. Key endotypes for asthma are type 2 high and type 2 low asthma[7,9]. Type 2 high inflammatory asthma often starts in childhood, at which age airway and peripheral blood eosinophilia, raised total and specific IgE and raised fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FENO) are observed and response to low-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) is usually good[7,8]. Typical type 2 cytokines that orchestrate this pattern are IL4, IL5 and IL13. Much less is known about type 2 low asthma in children and, in general, there are few treatment options (see Figure 2[10])

Shutterstock.com/The Pharmaceutical Journal

Phenotyping leads to non-specific treatments whereas endotyping leads to more targeted, precision medicine[8,9].

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of asthma include wheeze, breathlessness, chest tightness and cough, and can be triggered by viral respiratory infections, changes in the weather, aero-allergens, such as house dust mite, mould, animals, pollen, air pollution, smoking and vaping[11,12]. These symptoms typically present in the preschool years, but in some cases can present in later childhood.

Severity of asthma can be determined by consideration of several factors, including symptom frequency, lung function tests, frequency of use of reliever therapies, activity limitation, number of exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids, hospital admission rates and unscheduled healthcare visits[13]. It is recommended that the severity of current symptoms can be judged by validated questionnaires, such as the ‘Children’s asthma control test’ (cACT) for children aged 4–11 years or the ‘Asthma control test’ (ACT) for those aged 12 years and older, but it should be noted that these results are subjective[2,12,13]. The British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network ‘British Guideline on the Management of Asthma‘ provides more information on severity of an attack, while the International European Respiratory Society and American Thoracic Society guidelines advise on evaluation and treatment[12].

Diagnosis

A detailed medical history is essential to the diagnosis, including symptom variability over time.

A list of points to cover during a consultation with a young person showing symptoms of asthma can be seen below.

Box: Points to cover in initial consultation with a young person and their family and/or carer

Does the patient wheeze and what type of wheeze is it?

Wheeze is a term that is often used imprecisely: many often call any form of noisy breathing a wheeze. An expiratory wheeze would usually be present in asthma but is not always the case. Use of the children and young people’s video footage from a parent/carer’s mobile phone should be considered to determine the noise being described.

Do they have a cough during the day or night?

A dry persisting cough is common in uncontrolled asthma particularly at night; however, an isolated dry cough without wheeze, chest tightness or breathlessness is rarely, if ever, caused by asthma.

Are symptoms worse at night?

This is a sign of uncontrolled disease.

What triggers the symptoms?

Common triggers include allergies (such as house dust mite, pollen, pets), viral illness, cold weather, mould, indoor (smoking and vaping) and outdoor air pollution or pests.

Is there a family history of asthma?

Atopy (i.e. predisposition to allergies) in first-degree relatives is common.

What is the patient’s social history?

Issues with damp, mould in the house, air pollution, smoking and vaping can exacerbate symptoms.

What treatments for the symptoms have been tried and with what response?

This is an important question to ask to inform any future treatments.

Although history taking is crucial, additional tests — such as spirometry and fractional exhaled nitric oxide FeNO — are recommended to both confirm an asthma diagnosis and monitor the effectiveness of treatment[14]. The interpretation of these tests is outside of the scope of the article; however, a raised FeNO result signifies high levels of eosinophilic inflammation in the airways that should respond well to steroids[15]. A reduced FEV1 (i.e. volume that has been exhaled at the end of the first second of forced expiration)/FVC (i.e. forced vital capacity) ratio, which is part of the spirometry reading, can be used to confirm the diagnosis and demonstrates obstruction that should be reversed by beta agonists. More information can be found in the ‘Association for Respiratory Technology and Physiology statement on pulmonary function testing’[15].

If the patient is not responding to treatments as expected, it is important to exclude diagnosis of other conditions that present with similar symptoms, such as vocal cord issues, enlarged tonsils, bronchiectasis or breathing pattern disorder[13]. Diagnosis of such conditions is outside the scope of this article and referral to an appropriate clinician is advised in this circumstance.

Pharmacy support following diagnosis

Training

The ‘National bundle of care for children and young people with asthma‘ has summarised actions and support systems to control and reduce the risk of asthma attacks and to prevent avoidable harm in children and young people. The training is based on a national capability framework for the care of children and young people with asthma divided into tiers based on different roles. The training can be accessed through ‘eLearning for Healthcare’ website[16].

The components are based on patient pathways and include environmental impacts, accurate and early diagnosis, effective preventative medicine, managing exacerbations, severe asthma, data and digital and asthma competencies, training and education needs.

It is important that pharmacists involved in the care of children and young people with asthma should be trained appropriately[17]. Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians can play a vital role in ensuring that children and young people with asthma get the basics right.

Education

Education should be provided on the importance of taking ICS regularly and when to take reliever medication, why they need to take/give the medication, and how the different medications work. This could also include information on triggers, air pollution, the green agenda and the risk of asthma exacerbations explained[13].

Information can be provided at any time the young person and their parents and/or carers present to the pharmacy to collect medication or for a pharmacy consultation.

The most important points to cover during a pharmacy consultation include inhaler technique, the importance of taking medication, and checking whether or not the patient has a personalised asthma action plan (PAAP) and ensuring they are adhering to it.

Various websites, such as Asthma and Lung UK, Moving On Asthma, Rightbreathe UK and Medicines for Children, can be used as reference sources and information downloaded from them to give to patients if required.

Inhaler technique

Data show that 80% of patients globally cannot use their inhalers correctly, which contributes to poor symptom control, risk of exacerbations and increased health economic burden[13,18]. It is important to demonstrate inhaler technique face to face and at every opportunity, particularly when a new device is started. To improve adherence, it is important that children and young people can and will use an inhaler.

To ensure effective use of the inhaler:

- Choose the most appropriate device for the patient considering physical problems and dexterity;

- Check the inhaler technique and ask children and young people/parent/carer to demonstrate how to use the inhaler;

- Correct technique where appropriate and recheck up to two or three times if necessary;

- Confirm that they can demonstrate correct technique[13].

Resources on inhaler technique for pharmacists include Asthma and Lung UK, Rightbreathe and the Centre for Postgraduate Pharmacy Education (CPPE) package on inhaler technique.

Spacers and devices

Patients can have differences in preference for inhaler devices and inhaler technique should be assessed for suitability with different devices. The most commonly prescribed delivery system for inhaled treatments is the pressurised metered-dose inhalers (pMDI) (e.g. Ventolin Evohaler, Clenil Modulite). This should be prescribed with a suitable spacer device for all CYP to optimise treatment delivery and negate the need for coordination of inhalation and device activation. A spacer device is excellent for taking medication at home but often it is not very portable for reliever medication.

- Children aged under three years should use a spacer with mask, making sure a good seal over mouth and nose is created. Link to video demonstration from Asthma and Lung UK (with mask) or Rightbreathe for healthcare professionals;

- Children aged three years and over with no additional needs are encouraged to use a spacer without a mask. Children aged over three with additional needs should be assessed on an individuals basis. Link to video demonstration from Asthma and Lung UK (without mask) or Rightbreathe for healthcare professionals.

- For young children (typically aged under 5 years) the ‘Rafi-tone’ app by Clin-e-cal Ltd. with a flo tone spacer (a training device that guides patients on correct pMDI use) is a useful aid to guide the child[5].

Children with neurodiversity may require extra time to adapt to their inhalers and transition to different devices; the Rafi-tone app is a very useful tool in these cases as it can reduce stress and anxiety around these medicines by making their use fun and interactive.

Some patients may prefer a breath-actuated device (e.g. Salamol Easi-breathe) or dry powder inhaler (e.g. Bricanyl Turbohaler); however, it is essential that patients are assessed as competent to use these devices. As a result, they are more likely to be prescribed to older children/teenagers, because younger children can not inhale strongly enough to get a full dose of medication. Ideally, similar device types should be prescribed for maintenance and reliever therapies.

Environmental factors, such as the carbon footprint of the device, should also be considered, but the appropriateness for the individual and asthma control is the primary concern[19].

Personalised asthma action plan (PAAP)

The use of a personalised asthma action plan can educate and support children and their parents and/or carers to appropriately self-manage their asthma. The plan, which is usually provided by a GP, asthma nurse or pharmacist, provides personalised information detailing regular treatment and what to do if asthma is getting worse or if the patient has an asthma attack. This plan should be created in collaboration with the children and young people/parent/carer, and it needs to be regularly updated and include what to do in an emergency[20].

Adherence

Poor adherence to asthma medication has been identified as a risk factor for life-threatening asthma attacks and, as a result, is the most important modifiable intervention to improve outcomes[6,21]. Medication adherence is complex and can be intentional or non-intentional often based on the behaviours and beliefs of individuals. There are three broad reasons for non-adherence based on the COM-B model; these are based on capability, opportunity and motivation[22]. Good adherence in asthma is defined as taking 80% of the prescribed medication[23].

Pharmacist interventions based on the ‘perceptions and practicalities approach’ (PAPA) has shown to be effective and using a shared decision making three talk method, based on “team talks”, “option talks” and “decision talks”, can help guide these interventions. More information on this method can be found in Elwyn et al. [23–26].

Pharmacists can help to identify poorly adherent patients by checking prescription records and identifying factors that may cause non-adherence. Prescription pick-up rates or medication possession ratios (calculated as the ratio of the number of days a patient is stocked for their medication to the number of days a patient should be stocked for their medication) may be used to assess adherence where poor adherence is suspected. However, electronic monitoring devices (EMDs) attached to inhalers are more accurate, although may not be available in routine clinical practice [27,28].

Smoking cessation and vaping

Children and young people may be exposed to second hand smoke exposure or may even be actively smoking or vaping. Some young people may not want to reveal if they smoke or vape in front of their parents, so it can be helpful to provide consultations they are able to attend on their own, especially as they are ready to transition to adults[12].

The number of young people vaping has increased in recent years, with 9% of those aged 11–15 years in the UK using e-cigarettes in 2021 compared with 6% in 2018, while experimental use of e-cigarettes in those aged 11–17 years has also increased to a staggering 50%, compared with the previous year, although this number may be inflated owing to inaccurate reporting[29]. The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health is urging the UK government to implement an outright ban on disposable e-cigarettes owing to potential health risks and the serious environmental impact[30].

The ‘NHS long-term plan’ identifies smoking and vaping as a modifiable factor in preventing lung disease and smoking cessation in all age groups[31]. Pharmacists play an important role providing young people and their parents and/or carers with advice on smoking cessation and identifying young patients that may be addicted to vaping[32,33]. The five ‘A steps’ can be used for successful intervention: ‘Ask’, ‘Advise’, ‘Access’, ‘Assist’, ‘Arrange’[34].

Vaccinations

Public Health England recommends flu vaccinations for children with asthma because flu causes serious complications, such as pneumonia, meningitis, encephalitis or death, and patients with asthma are at a higher risk[35]. Encouraging uptake of all childhood vaccinations is another important role that pharmacists can play and reduces attack rate[35,36].

New medicines service and discharge medicines service

The new medicines service and discharge medicines service offer pharmacy teams an opportunity to address all the points above. Structured medication reviews can be used to address the points above and promote shared decision-making conversations[37]. Examples of structured medication templates can be found on EMIS and System One and the CPPE website[37–39].

Annual review templates can be found on the national asthma bundle websites and various GP systems. It is recommended that reviews should be conducted face to face and include inhaler technique checks, adherence to ICS, review of short-acting beta agonist (SABA) overreliance, a review and/or a co-created PAAP, medicines optimisation with a collaborative approach and shared decision making.

Identifying children and young people at risk of asthma exacerbations

Pharmacists can identify patients/families that do not pick up regular ICS, use more than three SABAs per year, use more than three courses of steroids per year owing to an asthma exacerbation, and flag these to the patient’s GP to trigger an asthma review.

Summary

Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians play an important role in supporting children and young people and their families with asthma through education, training and adherence to medication. Children and young people with asthma still continue to die through lack of basic knowledge and checks, and pharmacists can play a vital role to ensuring asthma deaths in children and young people do not happen.

Useful resources

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline [NG80]: ‘Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management‘;

- British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network ‘British Guideline on the Management of Asthma‘;

- Global Initiative for Asthma;

- Irish College of GPs ‘Asthma – Diagnosis, Assessment and Management in General Practice Quick Reference Guide‘.

- 1Pavord I, Beasley R, Agusti A, et al. After asthma: redefining airways diseases. Lancet 2018;391:350–400. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30879-6

- 2Asthma Clinical Knowledge Summary. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2022.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/asthma/ (accessed Jul 2023).

- 3Ferrante G, La Grutta S. The Burden of Pediatric Asthma. Front. Pediatr. 2018;6. doi:10.3389/fped.2018.00186

- 4Keeble E, Kossarova L. QualityWatch Focus on: Emergency hospital care for children and young people – What has changed in the past 10 years? . Nuffield Trust. 2017.https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-10/1540142848_qualitywatch-emergency-hospital-care-children-and-young-people-full.pdf (accessed Jul 2023).

- 5Shah R, Hagell A, Cheung R. International comparisons of health and wellbeing in adolescence and early adulthood. Nuffield Trust. 2019.https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/international-comparisons-of-health-and-wellbeing-in-adolescence-and-early-adulthood (accessed Jul 2023).

- 6Why asthma still kills. Royal College of Physicians. 2015.https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/why-asthma-still-kills (accessed Jul 2023).

- 7Martin J, Townshend J, Brodlie M. Diagnosis and management of asthma in children. bmjpo. 2022;6:e001277. doi:10.1136/bmjpo-2021-001277

- 8Bush A. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Asthma. Front. Pediatr. 2019;7. doi:10.3389/fped.2019.00068

- 9Kuruvilla ME, Lee FE-H, Lee GB. Understanding Asthma Phenotypes, Endotypes, and Mechanisms of Disease. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol. 2018;56:219–33. doi:10.1007/s12016-018-8712-1

- 10Pijnenburg MW, Fleming L. Advances in understanding and reducing the burden of severe asthma in children. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2020;8:1032–44. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30399-4

- 11Bush A. Asthma: What’s new, and what should be old but is not! Pediatr Respirol Crit Care Med. 2017;1:2. doi:10.4103/prcm.prcm_11_16

- 12BTS/SIGN British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. The British Thoracic Society. 2019.https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/ (accessed Jul 2023).

- 13Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Global Initiative for Asthma. 2022.www.ginasthma.org (accessed Jul 2023).

- 14Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2017.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80 (accessed Jul 2023).

- 15Sylvester KP, Clayton N, Cliff I, et al. ARTP statement on pulmonary function testing 2020. BMJ Open Resp Res. 2020;7:e000575. doi:10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000575

- 16National Bundle of Care for Children and Young People with Asthma programme. elearning for healthcare. 2023.https://www.e-lfh.org.uk/programmes/children-and-young-peoples-asthma/ (accessed Jul 2023).

- 17National Bundle of Care for Children and Young People with Asthma: Phase one. NHS. 2019.https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/B0606-National-bundle-of-care-for-children-and-young-people-with-asthma-phase-one-September-2021.pdf (accessed Jul 2023).

- 18Usmani OS, Lavorini F, Marshall J, et al. Critical inhaler errors in asthma and COPD: a systematic review of impact on health outcomes. Respir Res. 2018;19. doi:10.1186/s12931-017-0710-y

- 19Best practice principles for inhaler prescribing. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2022. doi:10.1211/pj.2022.1.151334

- 20Your child’s asthma action plan. Asthma + Lung UK. 2020.https://www.asthmaandlung.org.uk/conditions/asthma/child/manage/action-plan (accessed Jul 2023).

- 21Levy ML. National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD). Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64:564.2-564. doi:10.3399/bjgp14x682237

- 22Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Sci. 2011;6. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

- 23Mes MA, Katzer CB, Chan AHY, et al. Pharmacists and medication adherence in asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:1800485. doi:10.1183/13993003.00485-2018

- 24Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, et al. A three-talk model for shared decision making: multistage consultation process. BMJ. 2017;:j4891. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4891

- 25Murphy AC, Proeschal A, Brightling CE, et al. The relationship between clinical outcomes and medication adherence in difficult-to-control asthma: Table 1. Thorax. 2012;67:751–3. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201096

- 26Santos P de M, D’Oliveira Júnior A, Noblat L de ACB, et al. Preditores da adesão ao tratamento em pacientes com asma grave atendidos em um centro de referência na Bahia. J. bras. pneumol. 2008;34:995–1002. doi:10.1590/s1806-37132008001200003

- 27Jochmann A, Artusio L, Jamalzadeh A, et al. Electronic monitoring of adherence to inhaled corticosteroids: an essential tool in identifying severe asthma in children. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1700910. doi:10.1183/13993003.00910-2017

- 28Pearce CJ, Fleming L. Adherence to medication in children and adolescents with asthma: methods for monitoring and intervention. Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 2018;14:1055–63. doi:10.1080/1744666x.2018.1532290

- 29Decrease in smoking and drug use among school children but increase in vaping, new report shows. NHS Digital. 2022.https://digital.nhs.uk/news/2022/decrease-in-smoking-and-drug-use-among-school-children-but-increase-in-vaping-new-report-shows (accessed Jul 2023).

- 30Children’s doctors call for an outright ban on disposable e-cigarettes. Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2023.https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/news-events/news/childrens-doctors-call-outright-ban-disposable-e-cigarettes (accessed Jul 2023).

- 31NHS Long-Term Plan. NHS. 2020.https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/ (accessed Jul 2023).

- 32NHS community pharmacy smoking cessation service. NHS England. 2022.https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/pharmacy/nhs-smoking-cessation-transfer-of-care-pilot-from-hospital-to-community-pharmacy/ (accessed Jul 2023).

- 33Chatziparasidis G, Kantar A. Vaping in Asthmatic Adolescents: Time to Deal with the Elephant in the Room. Children. 2022;9:311. doi:10.3390/children9030311

- 34Five Major Steps to Intervention (The ‘5 A’s’). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2012.https://www.ahrq.gov/prevention/guidelines/tobacco/5steps.html (accessed Jul 2023).

- 35The national influenza immunisation programme 2022-23. UK health Security Agency. 2022.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/flu-vaccination-programme-information-for-healthcare-practitioners (accessed Jul 2023).

- 36Immunisations – Seasonal Influenza. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2022.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/immunizations-seasonal-influenza/ (accessed Jul 2023).

- 37Structured medication review. NHS England. 2020.https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/SMR-Spec-Guidance-2020-21-FINAL-.pdf (accessed Jul 2023).

- 38Structured medication reviews. Oxford Academic Health Science Network. 2023.https://www.oxfordahsn.org/our-work/respiratory/asthma-biologics-toolkit/asthma-structured-medication-review-template/ (accessed Jul 2023).

- 39Structured medication review. Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education. https://www.cppe.ac.uk/programmes/l/medrev-ec-01 (accessed Jul 2023).