Shutterstock.com

After reading this learning article, you should be able to:

- Understand the difference between gastro-oesophageal reflux and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease;

- Identify the signs and symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease;

- Identify the ’red flags’ and when to refer;

- Understand the treatment options.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) is the involuntary passage of gastric contents into the oesophagus[1]. In children, it is often a simple physiological phenomenon — especially in infants in cases of regurgitation that appear to happen unnoticed by the child. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) occurs when the reflux of gastric contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications. It is one of the most common causes of foregut symptoms across all paediatric age groups[1,2].

In clinical practice, the terms GOR and GORD are often used interchangeably by healthcare professionals and families. There is no simple, accurate and reliable diagnostic test to confirm whether the condition is GOR or GORD, which affects research and clinical decisions. It is therefore difficult to identify patients who have GORD, and to estimate the real prevalence and burden of the condition. Regardless of the exact definition, GORD affects many children in the UK and, as parents and carers commonly seek medical advice, it constitutes a health burden for the NHS[3,4].

Physiological GORD occurs in around 40–65% of all otherwise healthy infants aged between 1 and 4 months[1]. Symptoms may begin before 8 weeks of age and become less frequent over time in around 90% of affected infants before they are 1 year[1].

It is important that pharmacists are aware of the symptoms and management of GORD in children, as they may need to assist in providing complex, tailored treatment plans as part of the multidisciplinary team.

Symptoms

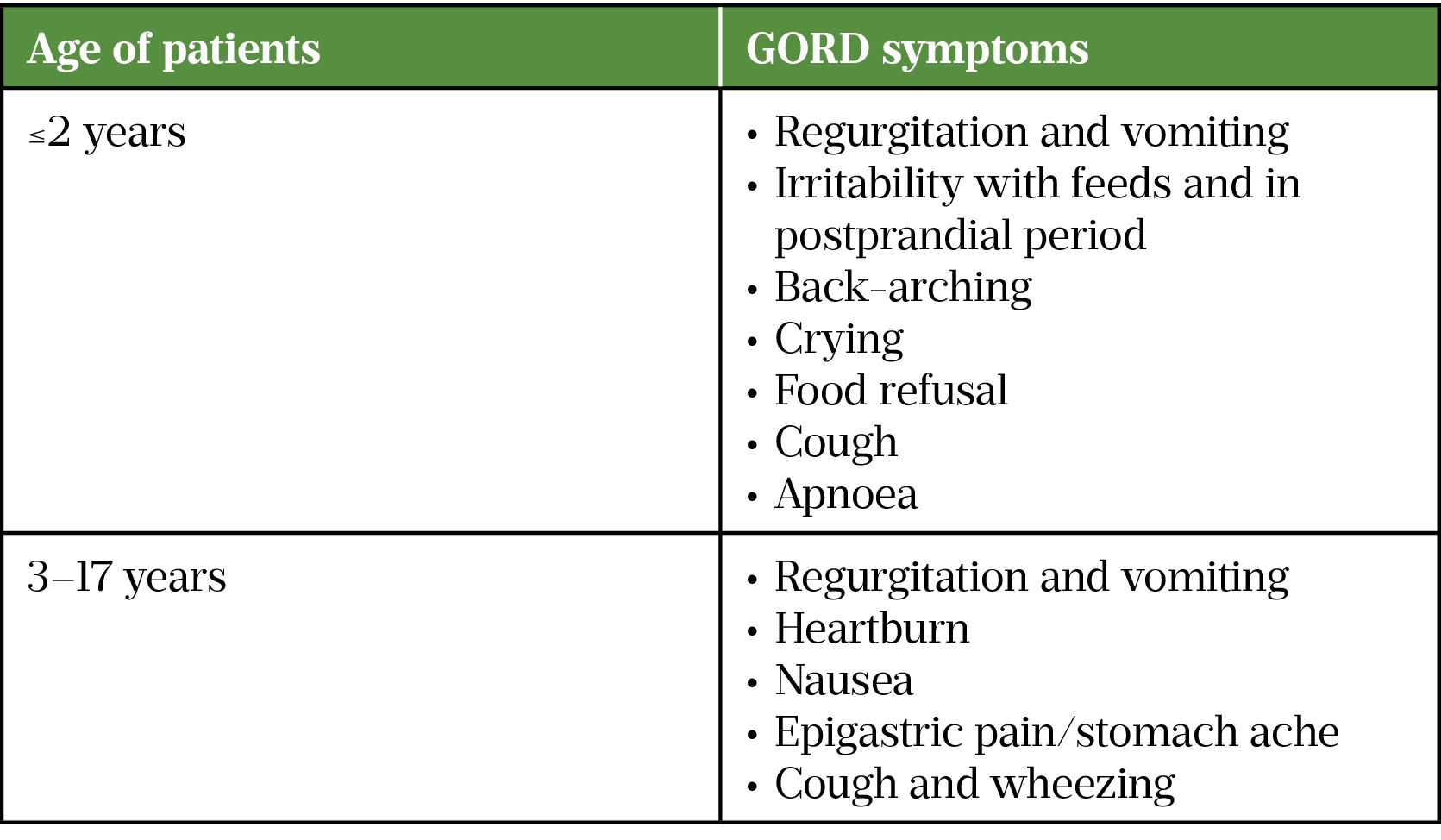

The symptoms of GORD can affect an individual’s quality of life and cause pathologic complications[1]. Symptoms may be frequent: 5% of those affected have as many as six or more episodes each day[3]. A list of common symptoms can be found in Table 1[1].

Infants and small children are unable to verbalise their symptoms, so non-verbal symptoms and signs have been used as a guide[1]. Irritability and back-arching in infants is thought to be an equivalent of heartburn in older children[1].

Symptoms are often non-specific and can either mimic or be caused by other infancy-related conditions, such as cow’s-milk protein allergy, pyloric stenosis, malrotation, overfeeding, tracheo-oesophageal fistula or constipation. Therefore, taking a thorough patient history is crucial for appropriate diagnosis and treatment[1].

The following factors are associated with an increased prevalence of GORD:

- Premature birth;

- Parental history of heartburn or acid regurgitation;

- Obesity;

- Hiatus hernia;

- History of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (repaired);

- History of congenital oesophageal atresia (repaired);

- Underlying neurodisability[3,4].

Diagnosis

Owing to GORD’s multifaceted clinical presentation and recurrent episodes of regurgitation in otherwise healthy children, discriminating ‘physiological’ GOR from ‘pathological’ GORD can be challenging, particularly in infants. However, making the distinction is crucial for the correct management of GORD, as it determines further investigations and treatment plans[1] .

European and North American Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN) guidelines list the conditions that put patients at a high risk of GORD complications (see Box 1).

Box 1: Conditions related to high risk of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease complications

- Neurologic impairment;

- Obesity;

- History of oesophageal atresia (repaired);

- Hiatal hernia;

- Achalasia (post-treatment);

- Chronic respiratory disorders (e.g. asthma, laryngitis, chronic cough);

- Bronchopulmonary dysplasia;

- Idiopathic interstitial fibrosis;

- Cystic fibrosis;

- History of lung transplantation;

- Premature birth[4,5].

Age-specific, symptom-assessing questionnaires would help the clinical diagnosis of GORD. However, to date, no single symptom or collection of symptoms has been shown to reliably identify patients with GORD or predict response to treatment[1].

Pharmacists should recognise that regurgitation of feeds is very common and normal in infants. It does not necessarily require any investigation or treatment and is managed by advising and reassuring parents and carers (see Box 2)[3].

Box 2: Advice about gastro-oesophageal reflux and how to reassure parents and carers

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux is very common (it affects at least 40% of infants);

- It usually begins before the infant is eight weeks old;

- May be frequent (5% of those affected have 6 or more episodes each day);

- Usually becomes less frequent with time (it resolves in 90% of affected infants before they are 1 year old);

- Does not usually need further investigation or treatment[1,3].

When to refer

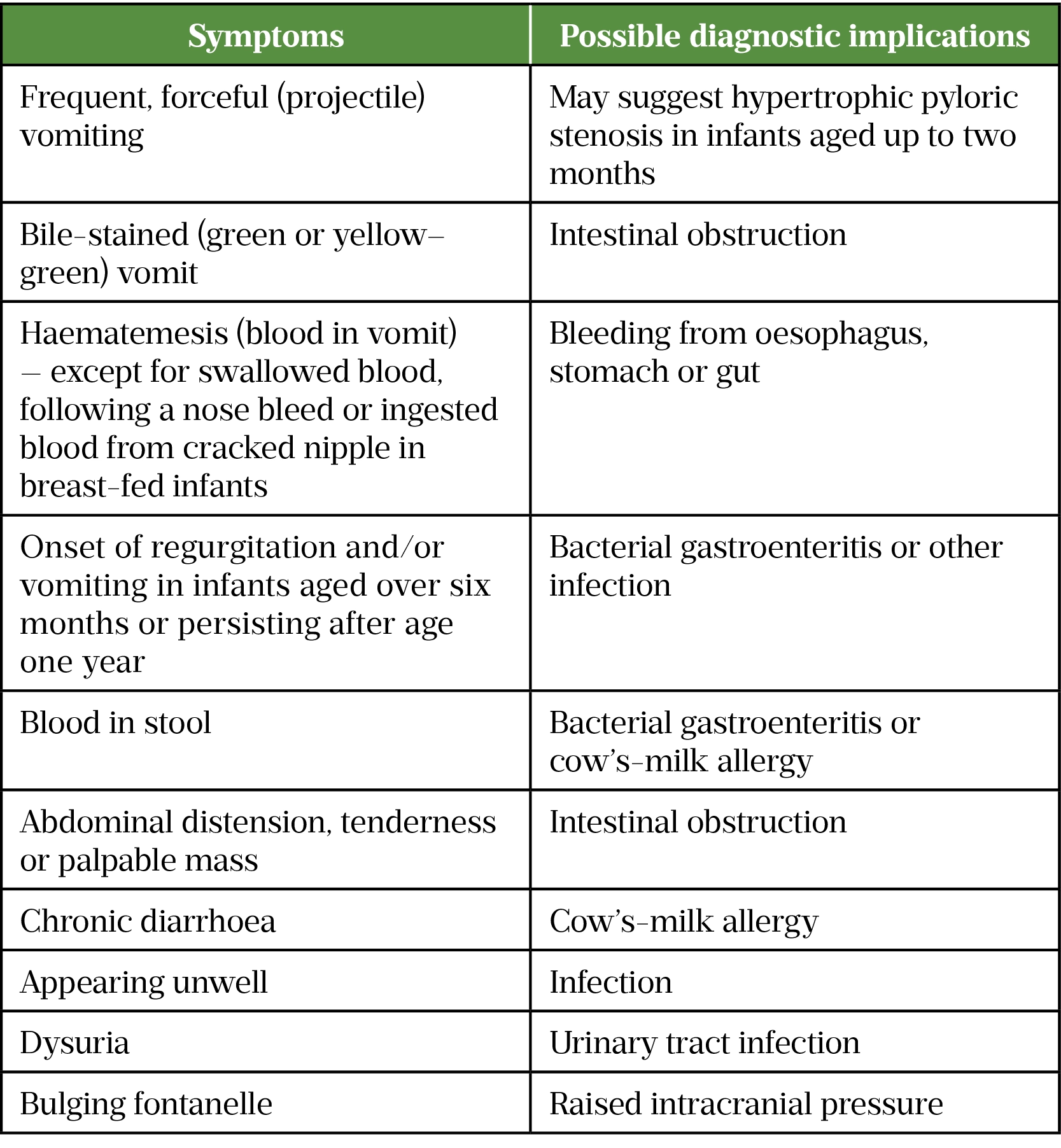

Children should be referred when:

- The regurgitation becomes persistently projectile;

- There is bile-stained (green or yellow–green) vomiting or haematemesis (blood in vomit);

- There are new concerns, such as signs of marked distress, feeding difficulties or poor weight gain;

- There is persistent, frequent regurgitation beyond the first year of life[3].

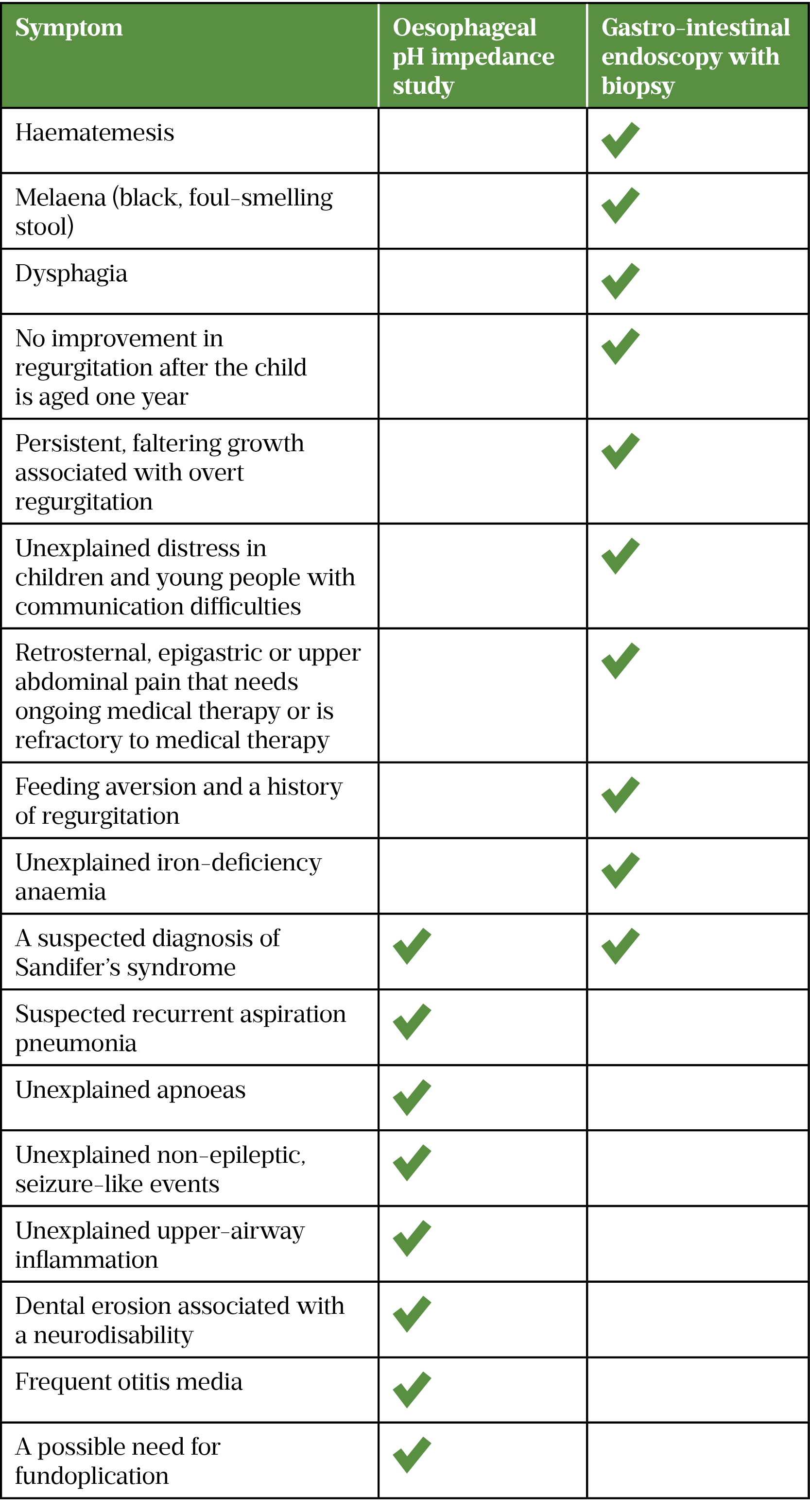

Red flag symptoms that require further investigations are listed in Table 2 and symptoms that warrant further investigation via oesophageal pH impedance study or gastro-intestinal endoscopy with biopsy are shown in Table 3[1,3,4].

Treatment

Therapy for paediatric GORD is based on a combination of conservative measures (i.e. lifestyle and dietary modifications), pharmacological and, rarely, surgical treatment.

Non-pharmacological management

Conservative management is the current first-line approach. It includes feeding and posture modifications, and modifying maternal diet (for breastfed infants)[3]. Prone or left lateral positioning has been shown to reduce GOR symptoms, as the gastro-oesophageal junction is clear of fluid in this position[6]. This may be possible in the neonatal nursery, as infants are monitored and continually observed (e.g. apnoea, cardiorespiratory and oxygen saturation monitoring). Outside of this environment, babies should be left to sleep on their backs.

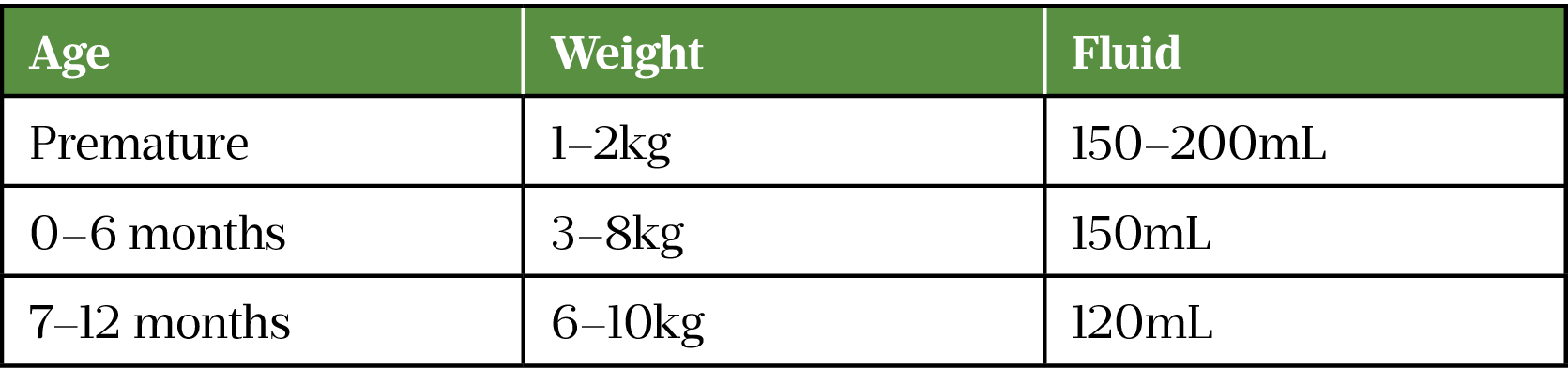

For otherwise healthy infants with GOR, the feeding management strategy has been proven to be effective[3]. It involves modifying feeding frequency and volume, and ensuring the intake of feed per kilogram of weight is appropriate (see Table 4)[7]. There is some evidence for the efficacy of the addition of feed thickeners (e.g. corn starch, rice starch, locust bean gum or carob bean gum) for one to two weeks on reducing the frequency of visible regurgitation[3].

If nutrition intake is still inadequate (failure to thrive) then tube feeding may be considered. This is usually considered alongside pharmacological treatment and will be based on consultation with parents and carers, considering the practicalities and support required.

Pharmacological management

Alginates, anti-secretory acid suppression and prokinetic drugs can be used to treat GORD. In infants, however, these agents must be reserved for patients with objectively assessed GORD and increased oesophageal acid exposure. Anti-secretory acid suppression drugs are the backbone therapy for GORD in infants[3].

Alginates

Gaviscon (Reckitt) is the most used alginate and is often enough to calm any reflux burning sensation and slightly thicken the feed. Its use also allows the parent or carer to know that they are helping their child in a way that is generally risk-free. As it thickens the feed mixture, parents should be made aware that they may need a teat with a larger hole for bottle feeds. Other means of thickening formula should be stopped if offering an alginate to avoid over-thickening[3].

Acid suppression

Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2-receptor antagonists are the main systemic treatments for problematic GORD. They should not be used to treat overt regurgitation in infants and children that occurs as an isolated symptom. Many of the products have licences that vary with age, therefore much of their use is off-label.

If using any of these treatments, a four-week trial is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)[3]. Owing to supply issues with ranitidine in 2021, PPIs have become the mainstay of treatment. Other H2-receptor antagonists are available, but none are licensed in infants and children, whereas some PPIs are[8].

Originally, solid-dose forms of PPIs were mixed with sodium bicarbonate to make solutions that could be divided into aliquots or dispersed in water to enable administration to children. Now, there are licensed products that fulfil these requirements and enable appropriate administration of any dose, can meet swallowing need and allow administration through gastric tubes[8].

Prokinetics

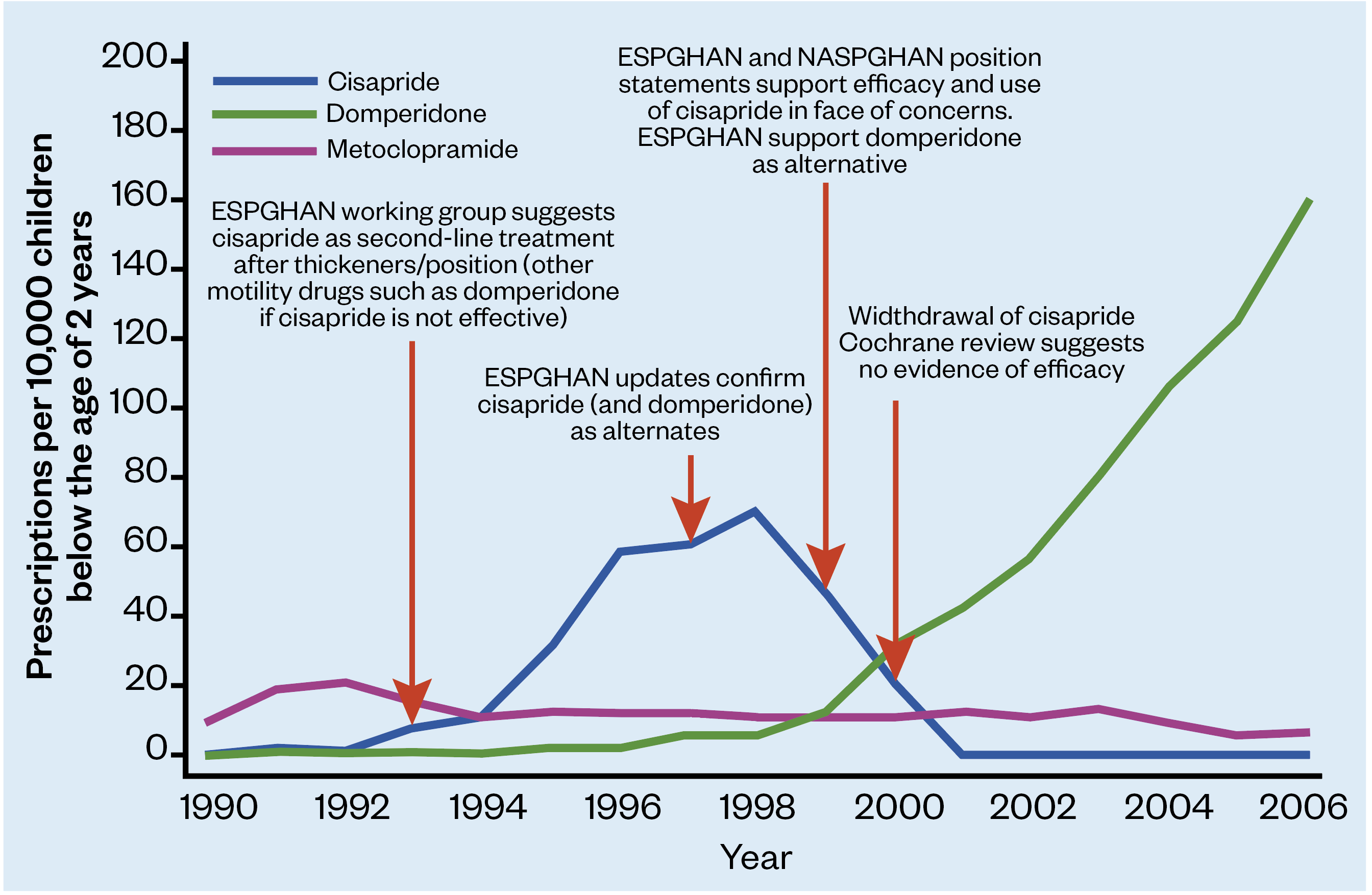

Cisapride (a licensed prokinetic) was removed from the market in 2000 owing to concerns of arrythmias in some children (9). Domperidone (off-label) was then used instead, but by 2012 there were national warnings alerting again to concerns of arrythmias. Domperidone is still occasionally used, but it should only be initiated by specialists and after careful consideration of the risks and benefits. Figure 1 shows the change between products based on the alerts supplied[9].

ESPGHAN: European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition

NASPGHAN: North American Society of Pediatric, Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition

Metaclopramide (off-label) should be reserved for serious vomiting, as children are more prone to the extrapyramidal side effects (e.g. drug-induced motor disorders) than adults[3].

Low-dose erythromycin is used as a prokinetic (off-label), but its efficacy and safety are poorly defined[10]. Use should only be initiated by a neonatal or paediatric specialist. Although it is seen as a relatively safe drug, the risk profile (e.g. hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, cardiac arrythmias and potential effect on a neonatal immune system) must be weighed against the risks of GORD[10].

Surgery

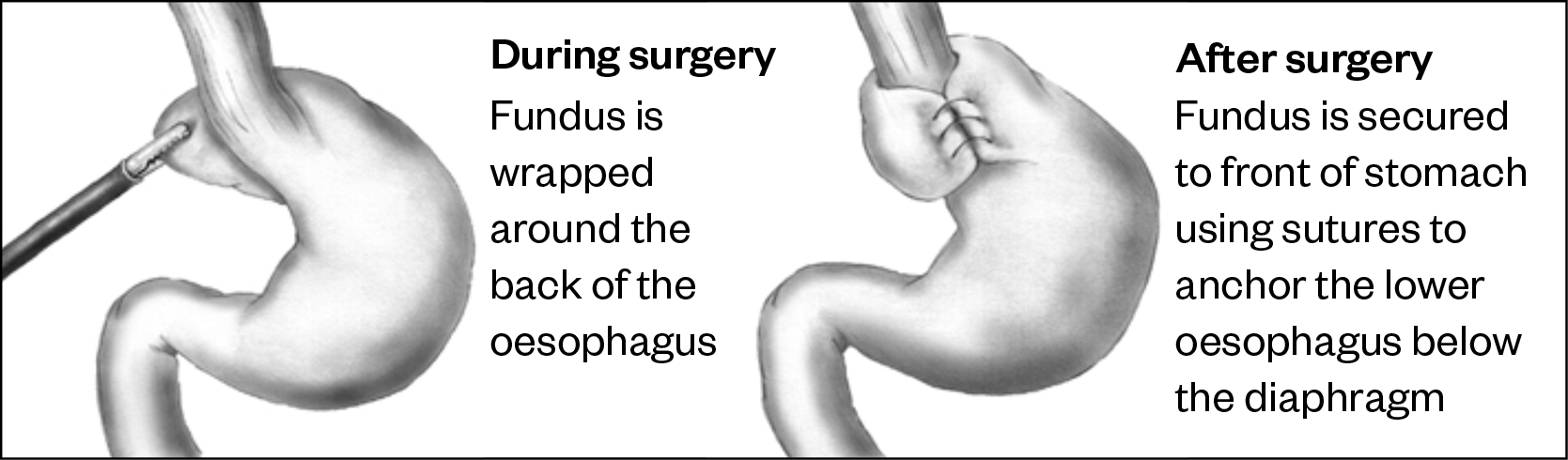

If pharmacological treatment has been unsuccessful, as well as feeding regimens to manage GORD, such as long-term, continuous thickened tube feeding, then surgery may be considered. Surgery — for example, fundoplication (a procedure that involves wrapping a part of the stomach around the lower part of the oesophagus; see Figure 2), may be considered for children with severe intractable GORD (usually assessed as severe failure to thrive and acute oesophagitis).

Duration, treatment review and follow-up

NICE recommends pharmacological treatment for four weeks for infants who have unexplained feeding difficulties (e.g. refusing feeds, gagging or choking), distressed behaviour and faltering growth, as well as for young children with persistent heartburn, retrosternal or epigastric pain. If the symptoms do not resolve or recur after stopping the treatment, referral should be made to a specialist for possible endoscopy.

Summary

It is likely that early identification and intervention in cases of GORD during childhood will result in an improved disease outcome, with fewer lifelong complications and an overall decrease in morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs.

Much of the treatment for GORD is aimed at supporting parents and carers through what is often a self-rectifying disease. Best practice for pharmacists is outlined in Box 3 and additional useful resources and practical advice can be found on the Medicines for Children website.

Box 3: Best practice for pharmacists

- Medicine optimisation is important in the successful management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in paediatric patients

- Pharmacists should:

- Communicate effectively with healthcare professionals across the multidisciplinary team, parents and carers to ensure patients receive maximum benefit from their treatment and that adverse drug events, including drug-drug interactions, are avoided;

- Respect patient, parent and carer preferences, approaching the formulation of management strategies holistically and with an open mind;

- Provide patients, their parents and carers with all the information about potential treatments through effective counselling to enable informed decisions to be made.

This article was reviewed by the expert authors in October 2024 to ensure it remains relevant and up to date, following its original publication in The Pharmaceutical Journal in May 2022.

- 1Rybak A, Pesce M, Thapar N, et al. Gastro-Esophageal Reflux in Children. IJMS. 2017;18:1671. doi:10.3390/ijms18081671

- 2Gold BD. Epidemiology and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux in children. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2004;19:22–7. doi:10.1111/j.0953-0673.2004.01832.x

- 3Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in children and young people: Diagnosis and management [NG1]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng1 (accessed May 2022).

- 4Onyeador N, Paul SP, Sandhu BK. Paediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: Table 1. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2014;99:190–3. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2013-305253

- 5Rosen R, Vandenplas Y, Singendonk M, et al. Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition. 2018;66:516–54. doi:10.1097/mpg.0000000000001889

- 6Corvaglia L, Rotatori R, Ferlini M, et al. The Effect of Body Positioning on Gastroesophageal Reflux in Premature Infants: Evaluation by Combined Impedance and pH Monitoring. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2007;151:591-596.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.06.014

- 7Nutritional Requirements for Children in Health and Disease. 7th ed. London: : Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust 2018.

- 8BNF for Children. Paediatric Formulary Committee. 2022.http://www.medicinescomplete.com (accessed May 2022).

- 9Mt-Isa S, Tomlin S, Sutcliffe A, et al. Prokinetics Prescribing in Paediatrics. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition. 2015;60:508–14. doi:10.1097/mpg.0000000000000657

- 10Patole S. Erythromycin as a prokinetic agent in preterm neonates: a systematic review. Archives of Disease in Childhood – Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2005;90:F301-f306. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.065250

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

excellent presentation