This content was published in 2008. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

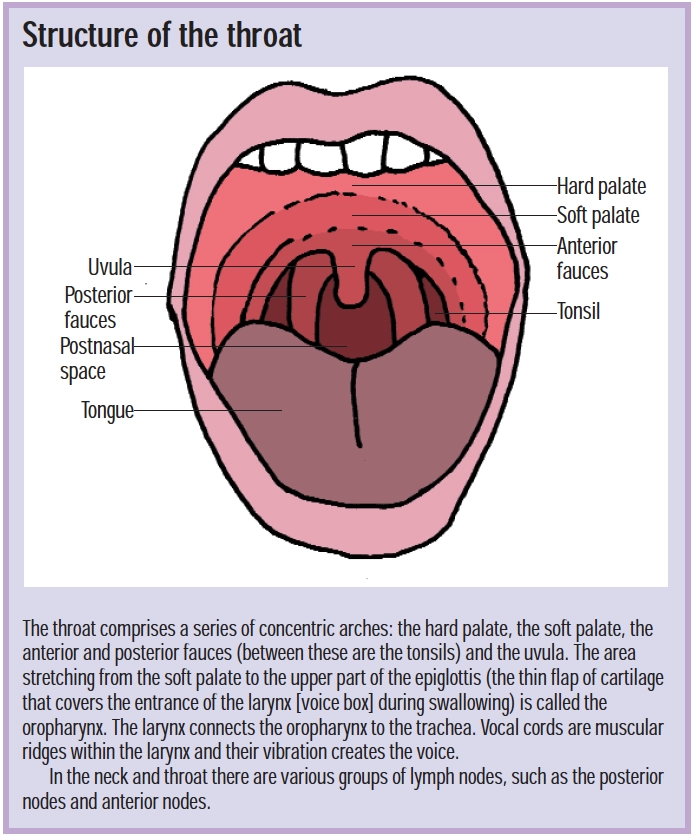

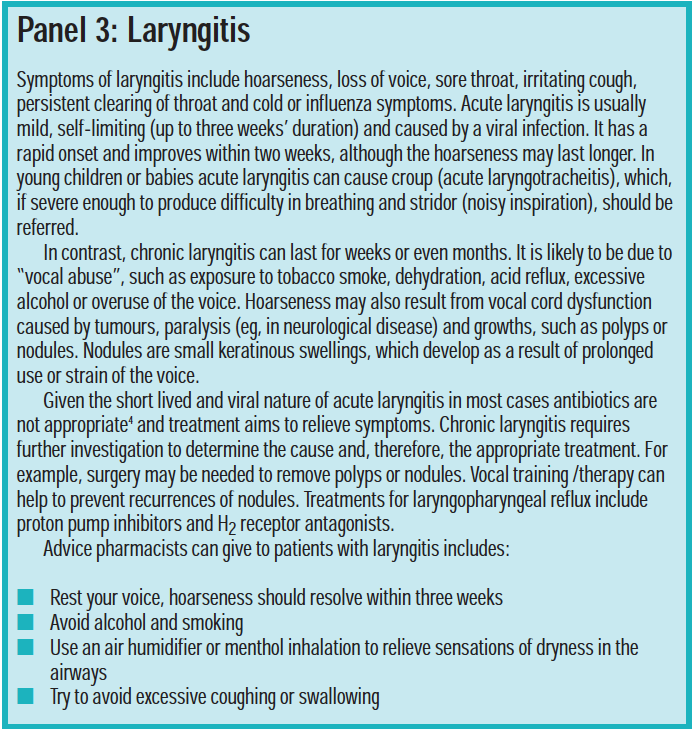

People use the term “sore throat” to describe pharyngitis, tonsillitis and laryngitis. Tonsillitis is inflammation due to infection of the tonsils, whereas pharyngitis is inflammation of the oropharynx only but, in practice, the distinction between the two can be unclear and they can occur simultaneously. “Laryngitis” is used when there is hoarseness with soreness lower down in the throat.

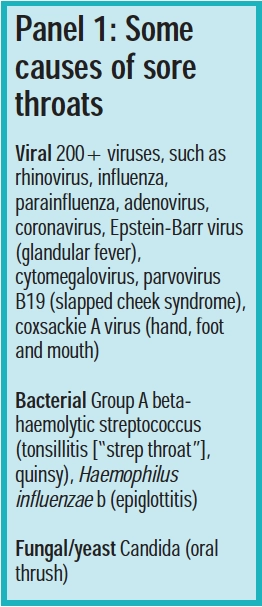

Sore throats are mostly minor and self-limiting and are often associated with a viral upper respiratory tract infection (at least 70 per cent of sore throats are the result of cold or influenza viruses1). However, there are numerous other infective causes (see Panel 1), including glandular fever.

A sore throat is often an early sign of chickenpox, mumps or measles. The most common bacterial pathogen is group A beta haemolytic streptococcus (GABHS), also known as Streptococcus pyogenes.

Non-infective causes include irritation by tobacco smoke, overuse of the voice (often seen in teachers or singers), laryngopharyngeal reflux, scalding (eg, after drinking hot liquids), some drugs (eg, steroid inhalers causing oral thrush in patients with asthma) and malignancy.

Adults experience two or three sore throats each year but incidence in children is higher. Children aged between five and 10 years and young adults aged between 15 and 25 years are the most frequently affected.2

Identify knowledge gaps

- Which ingredient in products for sore throats has antibacterial and antifungal activity?

- Why should a person with a sore throat not usually be prescribed a broad spectrum penicillin?

- Why should patients complaining of a sore throat and taking carbimazole be referred to their GP immediately?

Before reading on, think about how this article may help you to do your job better. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s areas of competence for pharmacists are listed in “Plan and record”, (available at: www.rpsgb.org/education). This article relates to “common disease states” (see appendix 4 of “Plan and record”).

Symptoms and diagnosis

In addition to a painful throat a person might complain of discomfort on swallowing, fever, headache and general malaise. Other possible accompanying symptoms include earache (pain or infection can spread along the Eustachian tube), loss of appetite and loss of voice or changes in voice. Glands in the neck may be tender and enlarged. Children often experience high fever, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting.

On examination, the tonsils or oropharynx may be red and swollen and flecks of whitish pus or a coating may be visible on the tonsils. GPs use an otoscope but pharmacists could keep a small torch at hand to make looking at a sore throat easier if they wish.

A sore throat is often the first sign of a cold or influenza. If this is the case, it is likely to pass within 48 hours and be followed by other symptoms, such as aches and a runny nose.

Classic streptococcal tonsillitis is common in schoolchildren. It is acute in onset and thesore throat is accompanied by headache and abdominal pain. There is intense redness of the tonsils and pharynx, with yellow exudate and painful swollen glands. However less than one third of patients exhibit these signs. A red rash (see below) is a further indication of streptococcal infection.

It is difficult to distinguish between a viral and bacterial infection. Throat swabs are rarely taken by GPs from patients suffering from sore throats, because they fail to differentiate between infection and carriage (6 to 40 per cent of the population is likely to carry GABHS, without symptoms2). In addition, the delay in processing results means they are of little use in routine diagnosis. However swabs may be useful when treatment has failed or in high risk patients (eg, those who are immunodeficient or who have diabetes).

Blisters on the throat may indicate hand, foot and mouth disease, while white patches on the mucosa of the mouth and soft palate may indicate candida infection.

When to refer

In most patients, a sore throat will resolve within a week. Pharmacists should refer a patient to his or her GP if:

- He or she cannot swallow liquids

- The sore throat is recurrent or lasts more than seven days

- He or she experiences prolonged (over three weeks) or repeated bouts of hoarseness

- He or she develops a red rash

- Earache, which does not resolve within 48 hours, develops

- The throat is painful, has not improved within 48 hours and there are no symptoms of cold or influenza

- Glands in the neck are swollen with no other symptoms or fail to go down within three weeks of a sore throat clearing

- He or she has had rheumatic fever

Young children may need earlier referral.

Some drugs (eg, carbimazole, propylthiouracil, gold salts, tolbutamide, phenothiazines) can reduce the numbers of neutrophils in the blood (resulting in neutropenia or, if severe, agranulocytosis), leading to increased susceptibility to infection. Patients taking such drugs and presenting with a sore throat should be referred urgently because this may be the first sign of drug-induced bone marrow suppression.

Patients with a sore throat and breathing difficulties should be referred to hospital immediately. These symptoms, combined with others, such as fever and drooling, may suggest epiglottitis, a rare but potentially life-threatening condition. If suspected, examination of the throat should not be attempted because this can block the airway. Patients with a persistent sore throat, with heavy night sweats and enlarged glands in the neck should be referred because these can be signs of lymphoma.

Treatment

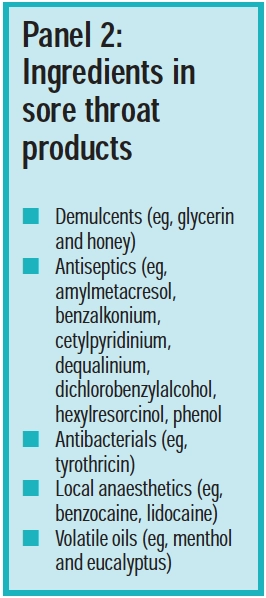

Once serious illness has been excluded, a sore throat can be tackled with over-the-counter products. Analgesics are the first choice. In clinical trials paracetamol and ibuprofen have been shown to be effective in relieving the pain of a sore throat3 and should be taken regularly to maximise pain relief. However, manymore products for sore throats are available. Formulations include lozenges, pastilles, syrups, gargles and throat sprays. Ingredients fall into several categories, including demulcents, antibacterials, local anaesthetics and volatile oils (see Panel 2).

Gargles have a short contact time with affected tissues, making relief transient. In addition, they do not reach the larynx, making them inappropriate in laryngitis (see Panel 3).

Gargles may wash infecting organisms out of the pharynx but studies have shown the level of contamination to be rapidly restored.5 Some people find a warm salty water gargle soothing. Patients should be advised not to swallow mouthwashes or gargles.

Aspirin gargles are a popular, but unproven, remedy for sore throats. One or two soluble aspirin tablets dissolved in a glass of water is gargled for three or four minutes, three or four times a day. The usual cautions and contraindications for aspirin apply.

Demulcents, such as glycerin, relieve irritation. Sucking lozenges or pastilles produces saliva, which soothes inflammation. It may also wash infecting organisms off the throat tissues. Demulcent products are safe for most people to take as often as necessary to relieve discomfort although the sugar content should be borne in mind. For people with diabetes, mouthwashes and gargles may be preferable due to their low sugar content. Sugar-free varieties of lozenges or pastilles are also available (eg, Bradosol, Strepsils sugar free).

Many products contain ingredients that have antiseptic, antibacterial or antifungal action. Tyrothricin is an antibacterial mixture of polypeptides and dequalinium (eg, Dequadinlozenges) has both antibacterial and antifungal activity. Given that most sore throats are caused by viruses, however, the value of such products may lie in their demulcent action.

Local anaesthetics numb the tongue and throat and may be useful for patients who find swallowing painful but sensitisation can occur with prolonged use.

Volatile oils (eg, menthol and eucalyptusoil), may have an analgesic effect as well as easing breathing through congested nasal passages.

Anti-inflammatory agents

Clinical trials have shown flurbiprofen, available OTC in lozenges (eg, Strefen lozenges), to be superior to placebo6 but data comparing this with other treatments is lacking. Flurbiprofen lozenges are contraindicated in children under 12 years old and in those already taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Side effects include taste disturbance and mouth ulcers. To avoid the latter, patients can be advised to move the lozenge around the mouth. Other cautions, contraindications and side effects are similar to those for NSAIDs in general.

Another anti-inflammatory, benzydamine, is available in a mouthwash and spray form (Difflam). It also has analgesic activity and may work by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis. It has been shown to be effective in reducing the symptoms of sore throat compared with placebo.7 Side effects include numbness and stinging of the mouth. Dilution of the mouth wash with an equal quantity of water can help. The duration of action of benzydamine is short, necessitating application every one and a half to three hours, for a maximum of seven days.

Antibiotics

In 2006, a systematic review showed that viral sore throats resolve by day 3 in 40 per cent of people and within a week in 82 per cent of patients, even if they are bacterial.8 According to this much cited review, the absolute benefit of antibiotics is modest, only shortening the duration of a sore throat by about 16 hours in the first week. However, although the review included some 12,000 subjects, few of the studies reviewed included children — the group that tends to be vulnerable to streptococcal tonsillitis. Clinical Knowledge Summaries recommends that antibiotics are prescribed if:

- There is marked systemic upset, secondary to an acute sore throat

- There is spread of infection to around the tonsils (unilateral peritonsillitis)

- The patient has had rheumatic fever inthe past (infections in these patients maypresent a cardiac risk)

- Other concurrent medical conditions increase the risk from acute infections

Antibiotics seemed to give a greater reduction in symptoms in those with throat swabs positive for streptococcus.8 They are also more likely to be of value when the infection appears clinically significant (eg, the presence of high fever, pus on the tonsils, enlarged painful glands in the neck or in those with a history of ear infections). The benefitof treatment must be weighed against the potential for adverse effects and increased bacterial resistance.

The first-line antibiotic for sore throats is phenoxymethylpenicillin. It has the advantages of efficacy, safety, a narrow spectrum (that includes GABHS) and low cost. Erythromycin is used for people who are allergic to penicillin, or in whom treatment has failed. It can also be used for children who find phenoxymethylpenicillin oral solution unpalatable.

Both these antibiotics are as effective as more expensive broader spectrum drugs. The duration of treatment with either antibiotic is usually seven or 10 days.2 Penicillin and erythromycin may be given four times daily or double the dose may be given twice daily.2 Because phenoxymethylpenicillin must betaken on an empty stomach the twice daily dosage may be more practical for many patients, especially young children.

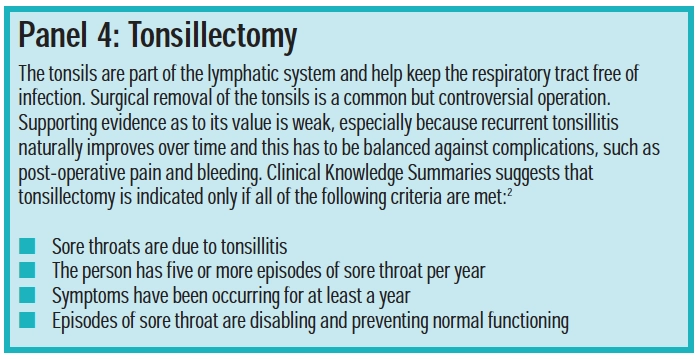

For reasons that are not fully understood,sore throat recurs in some patients treatedwith antibiotics. In severe or recurrent cases larger doses or longer courses may be necessary. Furthermore, tonsillectomy may sometimes be indicated (see Panel 4).

Sore throat can also be a symptom of glandular fever (see Panel 5).

Complications

Complications of sore throat include otitis media (particularly in children under five years), sinusitis, quinsy, scarlet fever, rheumatic fever and acute glomerulonephritis.

Quinsy is an abscess forming around the tonsil, following tonsillitis. Symptoms are acute sore throat (often worse on one side), fever, drooling, and swelling in the neck or face. It can be severe enough to restrict breathing but is rare. Quinsy can be treated with phenoxymethylpenicillin but, if severe, requires hospital admission, intravenous antibiotics and fluids, and drainage of the abscess under local anaesthetic.

Some patients with tonsillitis due to GABHS are sensitive to the erythrogenic toxins produced by the bacteria and come out in a red rash, which typically starts at the neck and spreads to the trunk. This is known as scarlet fever. Infection is most common in children between the ages of four and eight years. Symptoms of streptococcal tonsillitis are accompanied by a white coated tongue through which red papillae protrude (a“white strawberry tongue”). Loss of the coating produces a “raspberry tongue” (red with prominent papillae). The face becomes flushed although the area around the mouth is pale.

Treatment of scarlet fever is as for streptococcal tonsillitis. Infection with GABHS can lead to acute glomerulonephritis or rheumatic fever, although these complications are rare in the UK. Some of the surface proteins on GABHS share certain amino acid sequences with some human tissue and it is thought that this leads to patients developing an immune response to their own tissues.

General advice

A GP with a list of 2,000 patients will see about 120 cases of sore throat annually2 and, in 1999, it was estimated that the cost to the NHS of GP consultations for sore throat was in the region of £60m per annum (before any treatment or investigation).10

Advice that pharmacists can give includes:

- Most sore throats are viral and self-limiting

- Symptoms can be relieved by analgesics/anti-inflammatory agents and OTC products if relevant

- Drink plenty of warm fluids

- Rest if you have a temperature

- Avoid cigarette smoke

- Take the full course of any prescribed antibiotics even if you feel better after a couple of days, discard any unused antibiotic at end of course

- Do not share toothbrushes or eating or drinking utensils with others

Action: practice points

Reading is only one way to undertake CPD and the Society will expect to see various approaches in a pharmacist’s CPD portfolio.

- Review your OTC preparations for sore throat and work out with colleagues which you would recommend and why.

- Next time you dispense a prescription for carbimazole check that the patient knows what to do if he or she develops a sore throat.

- With your staff, make a list of questions you would ask a customer requiring an OTC treatment for a sore throat.

Evaluate

For your work to be presented as CPD, you need to evaluate your reading and any other activities. Answer the following questions: What have you learnt? How has it added value to your practice? (Have you applied this learning or had any feedback?) What will you do now and how will this be achieved?

References

- Edwards C, Stillman P. Minor illnesss or major disease? The clinical pharmacist in the community. 4th edition. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2006.

- Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Sore throat — acute. Available at www.cks.library.nhs.uk/sore_throat_acute (accessed on 8 January 2008).

- Kenealy T. Sore throat. BMJ Clinical Evidence 2008;01:1509 available at http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com (accessed on 10 January 2008)

- Reveiz L, Cardona AF, Ospina EG. Antibiotics for acutelaryngitis in adults (review). Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2007. Issue 2. Available at www.cochrane.org (accessed on 8 January 2008)

- Nathan A. Non-prescription medicines. 3rd edition. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2006.

- Blagden M, Christian J, Miller K, Charlesworth A. Multidose flurbiprofen 8.75mg lozenges in the treatment of sore throat: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in UK general practice centres. International Journal of Clinical Practice 2002. 56:95–100.

- Wethington JF. Double-blind study of benzydamine hydrochloride, a new treatment for sore throat. Clinical Therapeutics 1985:7;641–6.

- Del Mar CB, Glasziou PP, Spinks AB. Antibiotics for sore throat (review). Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2006. Issue 4. Available at www.cochrane.org (accessed on 8 January 2008).

- Candy B, Hotopf M. Steroids for symptom control in infectious mononucleosis (review). Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2006. Issue 3. Available at www.cochrane.org (accessed on 8 January 2008).

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of sore throat and indications for tonsillectomy. Available at www.sign.ac.uk (accessed on 8 January 2008).

You might also be interested in…

Risks of nasal decongestant spray overuse need to be made clearer, says RPS

More than 5,000 patients treated for ear problems under community pharmacy pilot