This content was published in 2011. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance

Key points

- Final graft function can range from excellent to fairly poor — as long as the patient does not require haemodialysis the transplant is considered a success.

- Prescribing post-transplant will be affected by the eGFR achieved.

- Acute transplant rejection or deterioration can present as a loss of urine output and rising serum creatinine.

In end-stage renal failure, drug and dietary therapy is no longer sufficient to manage poor kidney function and renal replacement therapy (RRT) with dialysis or a transplant is necessary. The latest Renal Registry figures report that in 2009 there were 49,000 patients on RRT in the UK, with just over half maintained on haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.

Current UK Renal Association guidelines1 state that transplantation is the treatment of choice for those who are fit for the major surgical procedure and lifelong immunosuppression. Life expectancy and quality of life are both substantially improved by transplantation and purchasers are spared the typical £30,000 annual cost per patient of providing haemodialysis. Since transplantation is only performed in 25 UK centres, good referral systems, communication and review of patients on the waiting list (held by NHS Blood and Transplant; NHSBT) are essential.

In March 2011 there were 6,900 patients waiting for a kidney in the UK. The mean wait for a cadaveric kidney is about three years. Patients referred for transplantation have their suitability for surgery and cardiac health reviewed, are encouraged to lose weight and stop smoking where needed, and are screened for viral infections, such as hepatitis B and cytomegalovirus (CMV). Patients not previously exposed to varicella zoster are vaccinated but this takes months to complete.

Patients must be made aware that transplantation carries a risk of death and, despite screening, transplanted kidneys can introduce a serious infection or malignancy into the patient. Immunosuppression also raises the risk of malignancy and infection generally.

Donor types and list criteria

Success (a working graft in a living patient) is about 95 per cent at 12 months and the mean duration of function is at least a decade, depending on factors including the donor’s health and age, tissue match and comorbidities in the recipient. The time the kidney is out of the body is also significant. Kidneys start to decay once their blood supply ceases. “Warm ischaemic time” (before the kidney is chilled with a cold perfusion solution) is limited to an hour. After removal and chilling, transplantation must take place within a day —“cold ischaemic times” of 10–20 hours are acceptable but longer periods are associated with poorer outcomes. Living donors now provide a third of all kidneys and are preferred due to better outcomes (possibly because those in poor health are excluded) and shorter ischaemic times. The availability of a living donor can also shorten waits, often allowing transplantation before haemodialysis is initiated. Tissue match is less important than in cadaveric donation, and it is even possible (although still uncommon) to transplant a live-donor kidney into a non-ABO blood group matched recipient.

Kidney donation generates complex psychological, legal and ethical issues, and requires careful preparation and consent, but it does not usually affect donors’ long-term health. Donors, typically parents, siblings or partners of the recipient, are in hospital for about a week and return to work after about a month. Where willing and able donors are not a match for their chosen recipient, NHSBT can arrange paired or pooled donation.

Cadaveric organ supply still provides two-thirds of kidneys. Most come from patients certified brain dead in intensive care units — and where ventilation and organ perfusion continues — but because these kidneys cannot meet demand, most centres are expanding the use of non-heart-beating donors. Donation after cardiac death involves the rapid removal of organs after a predicted cardiac arrest, within the allowed warm ischaemic time and, since this is not precisely predictable, hospitals are faced with challenges to provide theatres and staff at short notice.

Patients without a suitable living donor are held on the waiting list. They are unlikely to be listed if their co-morbidity and history predicts either a life expectancy or a graft survival of less than five years. Listing is also unlikely for those with a history of noncompliance, psychosis or drug abuse, or recent malignancy or chronic infections.

Deceased donor kidneys are allocated according to criteria which aim to help those who will benefit most. Children with complete matches are allocated kidneys preferentially because they will need several transplants throughout their lives and it is important to avoid sensitisation to foreign proteins. NHSBT allocates kidneys favouring, among other factors:

- Those who have waited longest;

- Well-matched transplants for younger patients;

- Closeness in donor and recipient age;

- Recipients located closer to the donor (i.e., minimising cold-ischaemic time)2.

Surgery and recovery

For live-donor transplants, surgery can be planned and the patients admitted the evening before. The graft is cross-matched with the recipient (to avoid unexpected incompatibility that would lead to a hyper-acute rejection) and his or her fitness for the operation is checked and consent obtained.

For cadaveric transplants, once a kidney becomes available, several prospective recipients may be located and brought to the transplant centre. This ensures availability of a suitable recipient but means those not eventually selected will be disappointed. Surgery typically takes three to four hours. In some ways, transplanting a kidney is a simpler procedure than removing one. The original kidneys are usually left alone and the graft placed low in the front of the abdomen and attached to the ileac artery and vein.

Induction therapy

As discussed in the CPD article (‘A rough guide to transplant medicines’) almost all patients receive some degree of immunosuppression induction to protect the kidney and enable doses of nephrotoxic calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) to be reduced. Practice varies between units but most patients receive 500mg–1g of intravenous methylprednisolone or equivalent perioperatively, and many also receive either two intravenous doses of basiliximab (Simulect) or two subcutaneous injections of the more potent alemtuzumab (MabCampath; “off-label”), often preceded by intravenous steroids, antihistamines and paracetamol.

Immediate post-operative period

Patients stay in hospital for five to 10 days. In the immediate post-operative period opioids are given by epidural or intravenous routes, often using patient-controlled analgesia pumps. Oral formulations are used once patients can swallow again. They may not be needed by discharge.

Intravenous fluids are tailored to meet normal needs and urine output, which may be either low or high. Laxatives, antiemetics and agents to prevent venous thromboembolism are used until no longer needed. Wound drains are removed within a couple of days.

Doses of renally cleared medicines are corrected for improving kidney function and oral maintenance immunosuppression, infection prophylaxis and sometimes aspirin (to prevent thrombosis in the new “renal artery”) are started.

Maintenance and prophylaxis

The most frequent choice for maintenance seems to be a combination of a CNI (commonly tacrolimus) and a mycophenolate preparation, both in twice daily formulations. Combination therapy aims to allow optimum immunosuppression with minimum adverse events. Some units still add in oral prednisolone, but often plan to withdraw it as quickly as possible to minimise adverse events.

Doses of CNI are initially weight-based, but following trough drug concentrations (initially performed several times a week) doses can be adjusted to within target range. In the longer term, trough level monitoring can be performed quarterly if there are no problems. Supplementation with (unlicenced) oral magnesium may be necessary to maintain normomagnesaemia while CNIs are prescribed. Patients should understand that:

- They need to stay on the same brand and formulation of CNI; in addition to Prograf and Advagraf there are now other brands of tacrolimus and the small differences in individual patient response can cause graft loss if inappropriate substitution occurs (Opinion is more divided on the interchangeability of mycophenolate brands);

- CNIs have a plethora of interactions, including with herbal products and grapefruit juice;

- Good adherence is necessary, and any adverse events should be reported and dealt with before self-alteration of regimens;

- Infections and malignant diseases are more likely now that they are immunosuppressed and sensible lifestyle measures are required;

- Any signs of graft dysfunction (eg, drop in urine production) should be reported quickly to enable a rapid response to rescue and preserve kidney function.

Prescribing prophylaxis against infection has become more common as the potency of immunosuppression has risen. Most patients receive six months’ therapy with low dose cotrimoxazole (e.g., 480mg od), which is cheap and prevents both Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia and toxoplasmosis, or dapsone.

If a patient who has not had CMV receives a CMV-positive kidney, three to six months of oral valganciclovir is usually given. This is an expensive medicine with five dose bands depending on clearance and requiring constant adjustment. Some units are starting to use this drug even when the recipient is CMV-positive. Oral nystatin, aciclovir and antituberculosis prophylaxis may also be used.

Outcomes

With regard to changes to medicines used before the transplant, no standard approach is possible due to variable outcomes. Grafts can take from hours to several weeks to begin to optimise functioning, especially those from older donors who died from cardiovascular disease or those with a long cold ischaemic time.

Final graft function can range from excellent to fairly poor but as long as the patient does not require haemodialysis the transplant is considered a success. Restoration of all kidney functions also varies, even though overall function may be good.

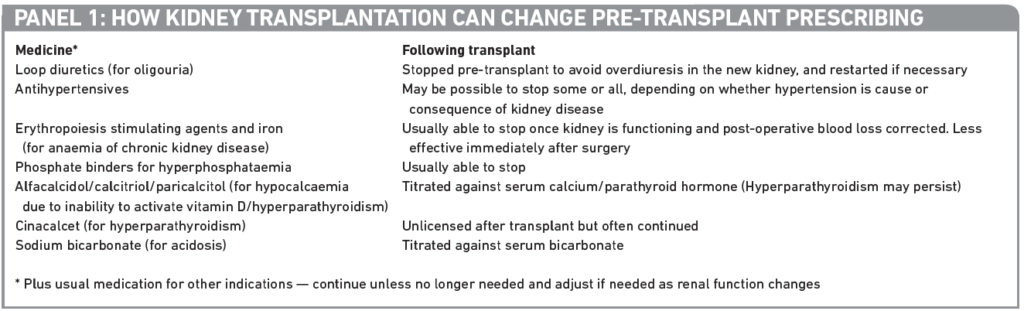

Pre-existing diseases, such as ischaemic heart disease, hypertension and diabetes mellitus, will still require treatment. Some pre-transplant medicines may, therefore, need to be continued, even if at a different dose. Typical changes to medication are shown in Panel 1.

Loss of graft function

Patients are intensively monitored during the first three months after transplantation, when acute rejection is most likely. Some patients will need higher drug levels than others, more potent immunosuppression, or even the introduction or reintroduction of oral steroids.

Acute rejection is not the only problem that can present as a loss of urine output and rising serum creatinine. Other common causes of acute deterioration in graft function include concurrent illness, dehydration and CNI toxicity. Investigations include:

- Trough CNI concentrations to check these are in range;

- Ultrasound to check kidney blood perfusion and drainage into the ureters;

- Blood or urine cultures and viral screens to identify infection;

- Biopsy to look at a tissue sample from inside the kidney if the cause is not obvious.

Nephrotoxicity caused by high CNI levels could be due to interactions with enzyme inhibitors (especially introduction of calcium channel blockers, erythromycin and fluconazole) or inappropriate product substitution. Withholding doses followed by dose reduction should restore function.

Low CNI levels, on the other hand, make rejection the most likely diagnosis and similarly could be due to:

- Inappropriate brand or formulation switches;

- Non-adherence (although this could be due to intolerable adverse events, especially gastrointestinal);

- Introduction of an enzyme inducer such as St John’s wort or certain antiepileptics.

Acute rejection is usually corrected with three days of intravenous methylprednisolone and adjustment of the underlying immunosuppression where needed.

Where a rejection is serious and has not responded to pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone, the prognosis for the graft is less optimistic and more aggressive therapy will be needed. Antithymocyte globulin, derived from rabbits, is licensed for this purpose, and rituximab is used in some cases; both require pre-treatment with steroids, paracetamol and antihistamines. Where these drugs are used outside the initial period of anti-infection prophylaxis, it is necessary to restart this.

Life and health after the transplant

It is the job of the transplant surgeon or nephrologist leading follow-up care to manage immunosuppression and other therapy to maintain a healthy patient and a functioning graft. Cardiovascular disease is a major risk and many patients have pre-existing hypertension or diabetes. A target blood pressure of <130/80mmHg is recommended; lower in proteinuria. All classes of antihypertensive can be used, following the usual criteria. Diabetes should be tightly controlled. Not only is it a mortality risk but it damages grafts. It is screened for because tacrolimus and other agents can cause it.

Dyslipidaemia is also common. It can exist before the transplant but is also aggravated by steroids, sirolimus, ciclosporin and, to a lesser extent, tacrolimus. Statins should be used if appropriate, to the same lipid targets as nontransplant patients, even though the evidence of benefit is weaker. Ciclosporin increases the AUC of some statins and a lower dose may be appropriate to avoid myalgia and myopathy. It is contraindicated with rosuvastatin, and the licensed dose of simvastatin limited to 10mg.

Healthy lifestyle advice is important and most units supervise screening programmes for skin and gynaecological cancers, promote avoidance of smoking, overexposure to the sun and contact with people with viral infections, and good food hygiene.

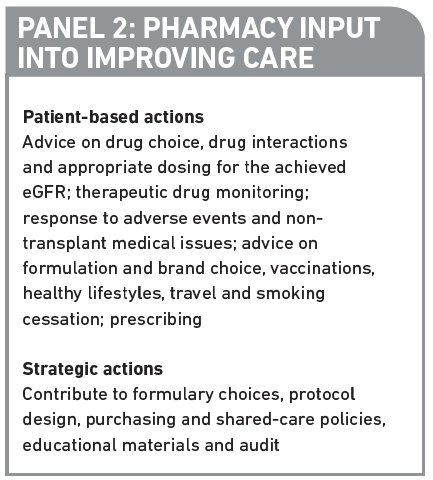

Transplant recipients should not receive live vaccines but they do need influenza vaccine annually and pneumococcal vaccine every five years, even though these may not generate the same response in the immunosuppressed. Patients who are now able to go on holiday (they no longer need dialysis) may seek advice from pharmacists on allowed vaccines for foreign travel, and if antimalarials are needed, interactions and appropriate dosing (for the estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR]). Panel 2 lists other ways in which pharmacists can improve the care of transplant patients. Most over-the-counter medicines can be used after transplant but pharmacists should check that they are not nephrotoxic and do not interact with CNI levels. For example, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and products containing potassium should be avoided.

Fertility improves after transplantation. For female patients, adequate contraception should be practised until the graft has been functioning well for a year or so, and the risks of the various immunosuppressants, some of which are contraindicated in pregnancy, have been discussed with the transplant unit and a specialist obstetrician.

Over time, immunosuppression is reduced where possible. Some units try to convert calcineurin-based therapies to the less nephrotoxic agent sirolimus.

Eventually, a combination of chronic rejection processes, ageing processes, drug toxicity, infections, hypertension and original morbidity conspire to put a finite life on the graft. At that point, immunosuppression is reduced to a minimum to prevent necrosis and dialysis restarted. If appropriate the patient can be relisted for a further transplant.

The citation information is currently unavailable. For more information please contact pharmpress-support@rpharms.com