Courtesy of Innovative Eye Care

Dry eye, also known as keratoconjunctivitis sicca, is one of the most common chronic eye conditions. The current widely accepted definition of dry eye is: “a multifactorial disease of the tears and ocular surface that results in symptoms of discomfort, visual disturbance and tear film instability with potential damage to the ocular surface. It is accompanied by increased osmolarity of the tear film and inflammation of the ocular surface”[1]

.

This definition was put together as part of a consolidation of the evidence about dry eye by the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS) and published as the DEWS report in 2007 (an updated version is due to be published in 2017).

Symptoms of dry eye include irritation, grittiness, burning, soreness, watery eyes and visual disturbances generally affecting both eyes[1],[2],[3],[4],[5]

. Dry eye is initiated through mechanisms of tear film hyperosmolarity and tear film instability and is broadly divided into two types: aqueous deficiency and evaporative dry eye[1],[2],[3],[4],[5],[6]

.

Evaporative dry eye is associated with an insufficient lipid oily layer coating to the tear film, such as when the meibomian glands (located along the lid margins) that produce it are damaged[7]

. Aqueous deficient dry eye, on the other hand, is a disorder in which the lacrimal glands fail to produce enough of the watery component of tears to maintain a healthy eye surface[1],[2],[3],[4],[5],[6]

. Dry eye is a continuum between these two states, with some treatments targeting evaporative dry eye (such as liposomal sprays[8]

) and others targeting the aqueous form (such as punctal plugging[9]

).

Large population epidemiological studies of dry eye have reported the prevalence to range from about 5% to more than 50%, with generally higher values in some Asian populations, although different definitions of dry eye between studies make comparisons difficult[10],[11],[12],[13]

. However, it is expected that the number of dry eye patients encountered in clinical practice may increase as the population ages.

In the community pharmacy

A recent unpublished survey by The Pharmaceutical Journal (see ‘Supplementary information [PDF]’) found that around two thirds of community pharmacists (n=227) spoke with patients about a dry eye condition more than once a week. However, mystery shopper studies have shown that differential diagnosis of dry eye conditions in UK pharmacy practices is poor[14]

. In one study, a diagnosis was given in the majority of consultations, suggesting that pharmacy staff members have confidence in their own ability to identify eye disease, which was supported by the lack of referrals advised to optometrists or GPs. Indeed, in The Pharmaceutical Journal survey, 81% of community pharmacists reported that they felt somewhat or very confident in diagnosing dry eye conditions. However, in the mystery shopper study, only 42% of pharmacy staff gave a correct diagnosis of dry eye[14]

.

The average number of questions asked by those giving a correct diagnosis was not dissimilar to those who gave an incorrect diagnosis but, notably, those who got the diagnosis correct were more likely to ask about the duration of symptoms, severity, laterality (one or both eyes affected) and whether or not there was any “dryness”

[14]

. Therefore, it appears from this study and from previous research[15]

that the specific questions asked, rather than the number of questions, is more important in formulating the correct diagnosis, and that certain answers carry more weight than others.

The diagnoses given by pharmacy staff also included sore eyes, tired eyes, hay fever, irritation, foreign body and infection. However, sore eyes, tired eyes and irritation are not considered diagnoses but symptoms of dry eye that may be present in other eye conditions. The packaging on some of the non-specific treatments using terminology such as “suitable for tired, uncomfortable and irritated eyes” may not help and could lead to the use of inappropriate treatments.

Risk factors

The 2007 DEWS report identified the risk factors for dry eye and classified them based on the quality of evidence (see ‘Table 1: Evidence for dry eye risk factors’)[12]

. Since the report, additional risk factors have been identified, including poor self-rated health, oral steroid use, benign prostatic hyperplasia (and the medicines used to treat it) and untreated thyroid disease. Lower risk was associated with sedentary lifestyles or use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Additionally, many medicines used to treat various ocular and systemic disorders may affect ocular surface health

[10]

.

| Table 1: Evidence for dry eye risk factors | ||

|---|---|---|

| Source: Smith JA, Albeitz J, Begley C et al. Ocul Surf 2007;5:93–107[12] | ||

| Mostly consistent | Suggestive | Unclear |

| Older age | Asian race | Hispanic ethnicity |

| Female sex | Tricyclic antidepressants | Cigarette smoking |

| Postmenopausal oestrogen therapy | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | Anticholinergics |

| Omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids deficiency | Diuretics | Anxiolytics |

| Antihistamine medicines | Beta blockers | Antipsychotics |

| Connective tissue disease | Diabetes mellitus | Alcohol |

| Laser refractive surgery | HIV/HTLV1 infection | Menopause |

| Radiation therapy | Systemic chemotherapy | Botulinum toxin injection |

| Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation | Large incision corneal surgery | Acne |

| Vitamin A deficiency | Isotretinoin | Gout |

| Hepatitis C infection | Low humidity environments | Oral contraceptives |

| Androgen deficiency | Sarcoidosis | Pregnancy |

| Ovarian dysfunction | ||

Diagnosis

The report of the DEWS diagnostic methodology subcommittee provided a thorough assessment of dry eye disease parameters, and compiled and evaluated a comprehensive database of assessment techniques for disease diagnosis and monitoring. These efforts resulted in a searchable database of tests for diagnosing and monitoring dry eye disease, with individual tests compiled and assessed by experts in the field and presented within standard templates (available at

www.tearfilm.org/dewsreport

)[16]

.

The report also highlighted the importance of differential diagnosis of dry eye to exclude conditions that have similar signs or symptoms that can confuse the diagnosis. The diagnostic methodology subcommittee determined that, from the numerous tests that were being used for diagnosing and monitoring dry eye disease, non-invasive tear film break-up time (the time taken to observe the first complete disruption in a light reflection off the tear film surface after a blink) represented the best means of evaluating tear film stability, with moderately high sensitivity and good overall accuracy[16]

.

Objective measures of dry eye, however, were largely unavailable and current tests are hindered by shortcomings. Problems include selection bias (how sensitive and specific a test appears depends on the inclusion or exclusion criteria chosen to select the population to test) and spectrum bias (a test is more likely to differentiate a group with severe disease than one with mild disease from healthy controls). Using a combination of symptomology and clinical tests is currently the most effective way to identify the signs and symptoms of dry eye and its subtypes. This information is critical if appropriate treatment is to be initiated for patients suffering from these conditions[16]

.

Management of dry eye to date has generally been informed by the presumed severity of an individual’s dry eye using grading tables, such as those devised by the Delphi Panel Report[17]

, which was adopted and modified by DEWS. This severity grading table includes symptoms (discomfort, severity and frequency), visual symptoms (mild to disabling or constant), ocular redness, staining of both the cornea and conjunctiva, tear film debris and corneal damage, eyelid gland blockage (meibomian gland dysfunction) or damage, tear film instability and tear volume[1]

.

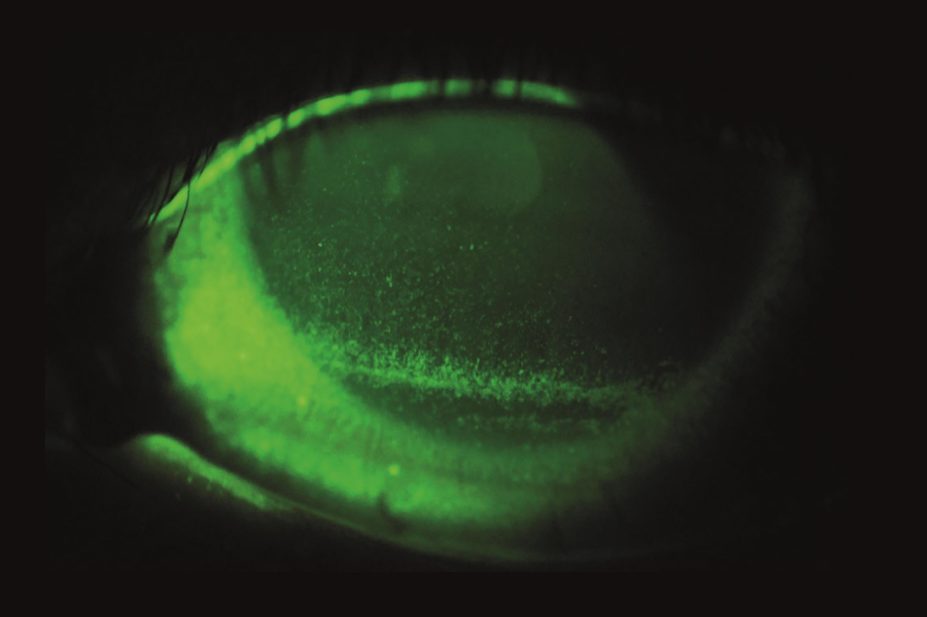

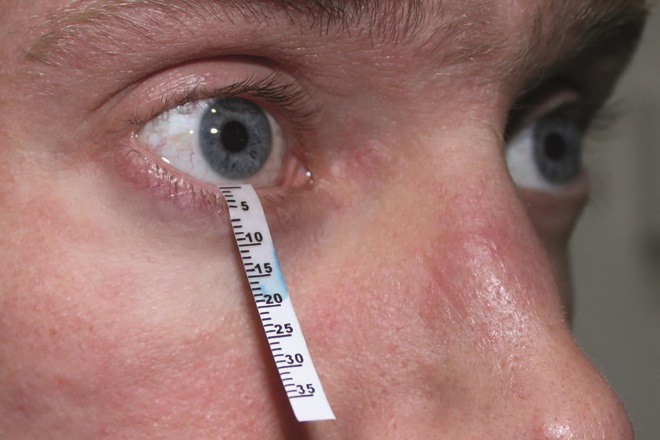

The two main diagnostic tests reported on the NHS Choices website are the fluorescein dye test (a vital dye thought to stain dead and dying cells principally on the cornea) and the Schirmer’s test (an invasive filter paper strip folded over the lower lid to absorb the tear film for a period of five minutes)[18]

. Despite the use of these tests as part of many dry eye clinical trials, neither ocular surface damage or tear volume are part of the current definition of dry eye

[1]

.

Source: Courtesy of Innovative Eye Care

The Schirmer’s test is an invasive filter paper strip folded over the lower lid to absorb the tear film for five minutes

The Optrex blink test and Systane non-invasive tear break-up time test require an individual to report how long they can prevent their eyes from blinking while staring at a screen, with ≤10 seconds leading to a suggestion that they may have dry eye. The results of both tests should not be considered a diagnosis, but may prompt a discussion with the pharmacist or healthcare professional. These tests seem to be imitations of tear break-up time clinical measures where a distortion in the tear film on the ocular surface ≤10 seconds has been associated with dry eye — but this does not necessarily trigger a blink[19]

. Although it is known that the blink rate is greater in dry eye, this reduces on staring, which is a requirement for the test[20]

. Hence, research would be needed to assess the efficacy of such a test as a diagnostic tool.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for dry eye disease are numerous[21]

. Conditions to consider include:

- Conjunctivitis (allergic, bacterial, giant papillary, medicamentosa and viral, as well as atopic and vernal keratoconjunctivitis);

- Sjögren’s syndrome (an autoimmune disease that damages mucosal glands, such as salivary and lacrimal glands, with lymphocytic infiltration) or connective tissue disorders (such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus or systemic sclerosis);

- Filamentary keratitis (a condition in which strands composed of degenerated epithelial cells and mucus develop on and adhere to the corneal surface causing pain and foreign body sensation);

- Infectious diseases (chlamydia, herpes simplex and herpes zoster);

- Corneal abnormalities (abrasion, erosion, foreign body and mucous plaques);

- Other keratitis (interstitial) and keratopathies (neurotrophic and pseudophakic bullous).

Hence particular attention needs to be paid to ‘red eye’ conditions and eyelid disease.

Factors that can assist in the differential diagnosis are[14],[22]

:

- Symptoms described in the patient’s own words: burning and dryness are common in dry eye conditions. Itchiness suggests allergic disease, and pain or a foreign body sensation suggests another cause;

- Quality of vision: visual quality is dependent on a smooth tear film over the ocular surface and so variability in vision between blinks is indicative of a dry eye condition;

- Duration and severity: dry eye severity typically varies with environmental conditions, such as humidity and wind speed, but is a chronic condition and is unlikely to have a sudden onset;

- Dry mouth and other mucosal tissues (such as swollen salivary glands for more than three months): this is indicative of Sjögren’s syndrome;

- Stickiness, crusting and discharge of the eye is an indication of an infectious cause, not a dry eye condition;

- An incident associated with the start of the symptoms, such as ocular surgery, starting contact lens wear, a foreign body entering the eye or starting a new medicine, can be indicative of a dry eye cause;

- Systemic conditions (such as allergy and connective tissue disorders) may induce dry eye. This will be alleviated by treatment of the root cause, although temporary treatment of the ocular surface dryness may still be appropriate in the meantime;

- One or both eyes affected: dry eye would generally affect both eyes so one painful or red eye increases the level of suspicion that this condition is not dry eye. However, the use of preservatives in eye drops, particularly benzalkonium chloride, can exacerbate dry eye[23]

. Therefore, a patient using this type of eye drop unilaterally may show greater signs and experience greater symptoms in the treated eye.

Some of these factors were discussed at a recent panel meeting about identifying and managing dry eye conditions in community pharmacies, held at the London headquarters of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, the professional membership body for pharmacy in the UK. Experts suggested several questions that may be useful in helping establish whether or not patients have a dry eye condition[24]

.

Other tests that help confirm the diagnosis but require specialist equipment include[16],[25]

:

- Slit lamp biomicroscopy: this involves high magnification observation of the eye with specific illumination techniques to observe and grade variations in ocular redness, meibomian gland ducts, tear film debris and tear meniscus height;

- Tear film stability: this is observed from the (specular) reflection off the tear film and how long after a blink this takes to break up;

- Tear volume: measured using filter paper strips (Schirmer’s test) or a thread with a pH indicator (phenol red test) hooked over the lower lid (for 5 minutes or 15 seconds, respectively);

- Ocular surface damage: identified using ophthalmic dyes to examine the cornea (sodium fluorescein) and conjunctiva/lid margins (lissamine green);

- Osmolarity: the tear film is susceptible to evaporation, increasing the relative salt content with damaging effects to the ocular surface. There is now a clinical test that can determine the osmolarity in the small volume of the tear film using electrical conductance;

- Laboratory testing: for conditions such as for Sjögren’s syndrome. For example, salivary function tests for salivary duct dilatation and delayed or absent secretion of labelled saliva; full blood count for anaemia; serology for antibodies to Ro or La antigens, or both.

Pharmacy staff should base their preliminary diagnosis on the factors outlined in the differential diagnosis section above. However, any cases where there is a reasonable level of uncertainty in the history and symptom-informed differential diagnosis should be referred to an optometrist (preferably one known to specialise in the condition), who can send the patient back to the pharmacist with an appropriate management plan. This will also allow the sub-classification of dry eye, such as aqueous deficiency or evaporative, to be identified and inform treatment. It can also be argued that symptomology alone is not a sensitive method for monitoring treatment effects[26],[27],[28],[29],[30]

so the pharmacist and optometrist should work in partnership.

Despite the NHS Choices website statement[18]

that “your GP should be able to diagnose dry eye syndrome based on your symptoms and medical history”, GPs do not generally have the specialised equipment necessary to diagnose and monitor dry eye disease any more than pharmacists do. However, patients may need to return to their GP to gain access to subsidised or prescription-only medicines if the optometrist or pharmacist are not qualified independent prescribers. Ophthalmologists may be involved in the management of very severe dry eye[31]

but NHS clinics generally do not have the capacity to deal with mild-to-moderate dry eye disease.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), in its clinical knowledge summary for dry eye syndrome, indicates an urgent same-day referral is required if a serious eye condition, such as acute glaucoma, keratitis or iritis, is suspected because of pain or photophobia, marked unilateral redness or reduced vision[32]

. Additionally, NICE recommends a routine referral or the provision of specialist advice where symptoms are uncontrolled despite appropriate treatment for four weeks, where vision deteriorates, where there is an indication of corneal damage, or where specialist assessment or management is required.

Information about the management of dry eye conditions in community pharmacies will be available in another article.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Lemp MA, Baudouin C, Baum J et al. The definition and classification of dry eye disease. Report of the definition and classification subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Workshop. Ocul Surf 2007;5:75–92. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70081-2

[2] Rieger G. The importance of the precorneal tear film for the quality of optical imaging. Br J Ophthalmol 1992;76:157–158. doi: 10.1136/bjo.76.3.157

[3] Goto E, Yagi Y, Matsumoto Y et al. Impaired functional visual acuity of dry eye patients. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;133:181–186. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01365-4

[4] Begley CG; Chalmers RL, Abetz L et al. The relationship between habitual and self-reported symptoms and clinical signs among patients with dry eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003;44:4753–4761. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0270

[5] Vitale S, Goodman LA, Reed GF et al. Comparison of the NEI-VFQ and OSDI questionnaires in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome related dry eye. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004;2:44. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-44

[6] Baudouin C. The vicious circle in dry eye syndrome: a mechanistic approach. J Fr Ophthalmol 2007;30:239–246. doi: JFO-03-2007-30-3-0181-5512-101019-200700462

[7] Nichols K, Foulks G, Bron A et al. The International Workshop on Meibomian Gland Dysfunction: Executive Summary. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2011;52:1922–1929. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997a

[8] Craig J, Purslow C, Paul J et al. Effect of a liposomal spray on the pre-ocular tear film. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2010;33(2):83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2009.12.007

[9] Sy A, O’Brien K, Liu M et al. Expert opinion in the management of aqueous Deficient Dry Eye Disease (DED). BMC Ophthalmology 2015;15(1):133. doi: 10.1186/s12886-015-0122-z

[10] McCarty CA, Bansal AK, Livingston PM et al. The epidemiology of dry eye in Melbourne, Australia. Ophthalmol 1998;105:1114–1119. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(98)96016-x

[11] Lin PY, Tsai SY, Cheng CY et al. Prevalence of dry eye among elderly Chinese population in Taiwan: the Shipai Eye Study. Ophthalmol 2003;110:1096–1101. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(03)00262-8

[12] Smith JA, Albeitz J, Begley C et al. The epidemiology of dry eye disease: report of the epidemiology subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Workshop. Ocul Surf 2007;5:93–107. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70082-4

[13] Chao W, Belmonte C, Benitez del Castillo J et al. Report of the inaugural meeting of the TFOS i2 = initiating innovation series: Targeting the unmet need for dry eye treatment. Ocul Surf 2016;14(2):264–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2015.11.003

[14] Bilkhu PS, Wolffsohn JS, Tang GW et al. Management of dry eye in UK pharmacies. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2014;37:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2014.06.002

[15] Julio G, Lluch S, Cardona G et al. Item by item analysis strategy of the relationship between symptoms and signs in early dry eye. Curr Eye Res 2012;37:357–364. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2012.654884

[16] Bron AJ, Abelson MB, Ousler G et al. Methodologies to diagnose and monitor dry eye disease: report of the diagnostic methodologies subcommittee of the international dry eye Workshop. Ocul Surf 2007;5:75–92. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70083-6

[17] Behrens A, Doyle JJ, Stern L et al. Dysfunctional tear syndrome. A Delphi approach to treatment recommendations. Cornea 2006;25:108–152. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000214802.40313.fa

[18] NHS Choices. Dry eye syndrome — diagnosis. Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dry-eye-syndrome/pages/diagnosis.aspx (accessed 11 May 2016)

[19] Mengher LS, Bron AJ, Tonge SR et al. A non-invasive instrument for clinical assessment of the pre-corneal tear film stability. Curr Eye Res 1985;4:1–7. doi: 10.3109/02713688508999960

[20] Argiles M, Cardona G, Perez-Cabre E et al. Blink rate and incomplete blinks in six different controlled hard-copy and electronic reading conditions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015;56:6679–6685. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16967

[21] Wirbelauer C. Management of the red eye for the primary care physician. Am J Med 2006;119:302–306. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.065

[22] Bilkhu P, Wolffsohn JS, Taylor D et al. The management of ocular allergy in community pharmacies in the United Kingdom. Int J Clin Pharm 2013;35:190–194. doi: 10.1007/s11096-012-9742-z

[23] Fraunfelder F, Sciubba J & Mathers W. The role of medications in causing dry eye. The Journal of Ophthalmology 2012;2012:285851. doi: 10.1155/2012/285851

[24] Lawrence J. Multidisciplinary panel of experts agree on best treatment of dry eye conditions in community pharmacy. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2016. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2016.20201187

[25] Smith J, Nichols KK & Baldwin EK. Current patterns in the use of diagnostic tests in dry eye evaluation. Cornea 2008;27:656–662. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605b95

[26] Hua R, Yao K, Hu Y et al. Discrepancy between subjectively reported symptoms and objectively measured clinical findings in dry eye: a population based analysis. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005296. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005296

[27] Moore JE, Graham JE, Goodall EA et al. Concordance between common dry eye diagnostic tests. Br J Ophthalmol 2009;93:66–72. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.131722

[28] Cuevas M, Gonzalez-Garcia MJ, Castellanos E et al. Correlations amongst symptoms, signs and clinical tests in evaporative type dry eye disease caused by meibomian gland dysfunction. Curr Eye Res 2012;37:855–863. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2012.683508

[29] Sullivan BD, Crews LA, Messmer EM et al. Correlations between commonly used objective signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of dry eye disease: clinical implications. Acta Ophthalmol 2014;92:161–166. doi: 10.1111/aos.12012

[30] Nichols KK, Nichols JJ & Mitchell GL. The lack of association between signs and symptoms in patients with dry eye disease. Cornea 2004;23:762–770. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000133997.07144.9e

[31] Valim V, Trevisani VFM, de Sousa JM et al. Current approach to dry eye disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunology 2015;49:288–297. doi: 10.1007/s12016-014-8438-7

[32] The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summary of Dry Eye. Available at: http://cks.nice.org.uk/dry-eye-syndrome#!scenario (accessed 25 May 2016)