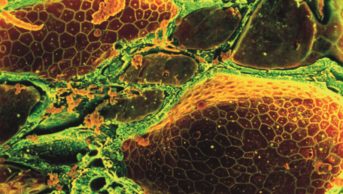

Barbara Galati/Getty Images

In this article you will learn:

- The groups of patients at risk of type 2 diabetes and when patients should be screened

- The signs and symptoms of diabetes

- How diabetes is diagnosed

Around 3.2 million people in the UK have been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus[1]

and there are an estimated 633,600 people with undiagnosed type 2 diabetes throughout the UK[2]

. Combined, this means around one in 17 people in the UK has diabetes. There are a further 11.5 million people in the UK who are at high risk of developing diabetes, many of whom could reduce their risk by improving their lifestyle through diet and exercise.

Type 1 diabetes typically affects children and young people, and is most commonly diagnosed at 10–14 years of age[1]

. It is an autoimmune disease that destroys the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas.

Type 2 diabetes accounts for nearly 90% of people with diagnosed diabetes. It is more common in older people and is a multifactorial disease resulting from the interplay of genetic and environmental factors, including obesity, excessive and unhealthy eating habits, lack of physical activity and stress. A key pathophysiological feature of type 2 diabetes is insulin resistance, the inability of normally-secreted insulin to move glucose into the cells for effective metabolism. This results in an initial overproduction of insulin, followed by a progressive decline in insulin production[1]

.

At-risk groups

Type 2 diabetes has clear modifiable risk factors, the most important of which is being overweight or obese (see ‘Risk factors for type 2 diabetes’). These also include poor diet and lack of physical activity.

There are also non-modifiable risk factors. Type 2 diabetes is six times more common in people of South Asian ethnicity, and three times more common among people of African and African-Caribbean ethnicity than the general population. Women who have a history of gestational diabetes have a 30% lifetime risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) states that providing structured lifestyle interventions in high-risk adult populations can prevent or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes[3]

.

In 2012, a UK expert committee recommended that people with a glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) of 42–47 mmol/mol (6.0–6.4%) should be considered as ‘high risk’[4]

. Patients with an impaired glucose tolerance or raised fasting glucose carry an increased risk of progression to type 2 diabetes and associated vascular complications.

Risk factors for type 2 diabetes

- Being overweight or obese (especially around the waistline)

- Poor diet

- Lack of physical activity

- Family history of type 2 diabetes

- Increasing age

- Hypertension or cardiovascular disease

- South Asian, African or African-Caribbean ethnicity

- High socioeconomic deprivation

- Impaired glucose regulation and/or raised HbA1c

- History of gestational diabetes

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- Taking antipsychotic medicines

Some individuals have blood glucose levels that are above the normal defined range but not high enough to be diagnosed as having type 2 diabetes. These people are described as having impaired glucose regulation or prediabetes. People with prediabetes are at higher risk of progressing to type 2 diabetes than the general population, and at a modest increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease.

Type 1 diabetes risk factors are less clear than those for type 2 diabetes. Although 85% of cases of type 1 diabetes occur in patients with no family history, there is a genetic link, and people with variations in the HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQB1 and HLA-DRB1 genes are at a greater risk of type 1 diabetes than the general population.

Patients who have a family member with type 1 diabetes are 15 times more likely to develop the condition than the general population (see ‘Risk of type 1 diabetes by affected family member’).

Environmental factors, such as exposure to Coxsackie B4 virus, rotavirus and cytomegalovirus, may also increase a patient’s risk of developing type 1 diabetes.

| Affected family member | Risk of developing type 1 diabetes |

|---|---|

| Source: Diabetes UK | |

| Mother | 2–4% |

| Father | 6–9% |

| Both parents | 30% |

| Sibling | 10% |

| Non-identical twin | 10–19% |

| Identical twin | 30–70% |

Signs and symptoms of diabetes

There is a general lack of awareness among the general population of the signs and symptoms of diabetes. In a survey of members of Diabetes UK with type 2 diabetes, only 16% received their diagnosis because they were alerted by their symptoms and asked their GP to investigate[5]

.

The insidious nature of type 2 diabetes means that up to 50% of patients will already have diabetic complications by the time they are diagnosed with the disease[2]

. This means the first presentation of type 2 disease might be a medical emergency, such as heart disease, stroke, blindness, renal disease, or peripheral vascular disease that could require limb amputation.

Almost a quarter of new cases of type 1 diabetes in children and young people, and almost 30% of cases in children under three years of age[6]

, will present with diabetic ketoacidosis. This is a potentially life-threatening condition that causes significantly elevated blood glucose levels, the presence of ketones in the blood and urine, and acidosis. Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis require emergency treatment with intravenous insulin and fluids, close monitoring in hospital and supportive management.

It is therefore essential for more people, particularly parents, to be aware of the signs of diabetes.

The classic signs of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes are the ‘4 Ts’: toilet, thirsty, tired and thinner. These symptoms typically occur more slowly in type 2 diabetes and may be missed by the patient, leading to a delay in diagnosis.

Toilet — someone developing diabetes will be passing more urine than normal, may need to uncharacteristically use the toilet at night, may wet the bed, or for babies/infants may have heavier nappies than normal. This is because the glucose in the blood exceeds the renal glucose threshold and is therefore excreted in the urine, which in turn causes increased water loss in urine.

Thirsty — as a result of passing more urine, the affected individual will feel thirsty and drink more fluids than normal. Passing more urine (polyuria) and increased thirst (polydipsia) are also known as osmotic symptoms.

Tired — the individual lacks the ability to utilise glucose for energy, which often causes tiredness.

Thinner — the body attempts to compensate for a lack of glucose in cells by metabolising protein and fat, which may result in weight loss.

Patients with diabetes may present with blurred vision, which is caused by a change in lens refraction due to hyperglycaemia. This normally improves once a patient’s glucose levels are normalised, and patients recently diagnosed with diabetes should not buy new glasses or contact lenses for the first three months after diagnosis.

Patients with diabetes are also at risk of recurrent infections (particularly fungal infections and urinary tract infections), which may be caused by the higher glucose concentration in blood and urine impairing phagocyte activity, and poor wound healing.

Screening and diagnosis

Systematic population screening for diabetes is not recommended by the UK National Screening Committee[7]

. However, NICE recommends that validated type 2 diabetes risk assessment is carried out in:

- All non-pregnant adults aged over 40 years;

- People aged 25–39 years of South Asian, Chinese, African-Caribbean, black African and other high-risk black and minority ethnic groups;

- Adults with conditions that increase the risk of type 2 diabetes (e.g. cardiovascular disease; hypertension; obesity; stroke; polycystic ovary syndrome; a history of gestational diabetes)[3]

.

NICE says staff working in community pharmacies are in an ideal position to carry out these risk assessments and to refer anyone with a high score to their GP for blood sugar tests[3]

. Pharmacy staff unable to carry out a risk assessment can advise patients to use validated self-assessment tools.

Patients who are suspected of having diabetes should be assessed further to confirm the diagnosis. Patients with diabetes will normally have a raised blood glucose level, a raised HbA1c (which is more likely to be markedly higher for those with type 2 diabetes) and glucose present in the urine. Patients with type 1 diabetes will also have ketones present in their urine and blood.

A patient is diagnosed with diabetes if they have symptoms of diabetes and any one of[8] ,[9]

:

- a random plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/l

- a fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/l (whole blood ≥ 6.1 mmol/l)

- a two-hour plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/l (taken two hours after a 75g glucose challenge in an oral glucose tolerance test)

- HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) on two separate occasions (usually taken two to four weeks apart).

In addition, patients can be diagnosed with prediabetes if they have any one of[3] ,[8] ,[9]

:

- a fasting plasma glucose of 6.1–6.9 mmol/l

- a two-hour plasma glucose of 7.8–11.0 mmol/l

- HbA1c of 6.0–6.4% (42–47 mmol/mol) on one occasion.

Patients diagnosed with prediabetes should be advised to improve their lifestyle, with a particular focus on improved diet and increased physical activity.

Pharmacists should recommend any person with two or more risk factors for diabetes to undergo diabetes screening tests every three years.

Elizabeth Hackett is principal pharmacist for diabetes and Winston Crasto is senior registrar in diabetes, both at University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust.

References

[1] Diabetes UK. Diabetes Facts and Stats [Online]. 2014 Available at: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/Documents/About%20Us/Statistics/Diabetes-key-stats-guidelines-April2014.pdf (accessed 8 October 2014).

[2] Diabetes UK. Early identification of people with diabetes [Online] 2014. Available at: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/early-identification-of-people-with-type-2-diabetes (accessed 6 October 2014).

[3] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Public Health Guidance 38: Preventing type 2 diabetes: risk identification and interventions for individuals at high risk. London: NICE 2012.

[4] John WG, Hillson R & Alberti SG. Use of haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. The implementation of World Health Organisation (WHO) guidance 2011. Practical Diabetes 2012;29:12-12a.

[5] Diabetes UK. State of Diabetes Care report 2009 [Online]. Available at: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/documents/reports/state-of-diabetes-in-the-uk-2009.pdf (accessed 11 October 2014).

[6] Diabetes UK. The Four Ts [Online] Available at: http://www.diabetes.org.uk/the4ts

[7] UK National Screening Committee. Screening for Type 2 Diabetes. June 2014. Available at: http://www.screening.nhs.uk/diabetes (accessed 6 October 2014).

[8] World Health Organization. Use of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Geneva: WHO 2011.

[9] World Health Organization. Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycaemia. Geneva: WHO 2006.

You might also be interested in…

Thyroid dysfunction and drug interactions