Barry Lewis / Alamy

In this article you will learn:

- How to assess patients for signs of overdose

- How to manage overdose caused by common illicit drugs

- The risks posed by legal highs

In 2010, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime estimated that between 153 million and 300 million people aged 15–64 years had used an illicit substance at least once in the previous year, and there were between 99,000 and 253,000 drug-related deaths (DRDs) globally. Not all cases of overdose ultimately result in a DRD but it can be a useful surrogate marker in determining both the drugs involved in overdoses and their relative potency.

Heroin or morphine was indicated in one in four of all DRDs reported in England and Wales for 2012–2013[1]

. Other drugs most commonly related to DRDs include methadone and other opioids such as tramadol, benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, amfetamine-type substances including novel psychoactive substances (NPSs), and cocaine.

Multiple drug use remains a significant problem in drug overdoses, and is mentioned on the death certificate in 40% of drug poisoning cases in England and Wales. Alcohol or long-term alcohol misuse was mentioned, in addition to another drug, in 30% of cases.

Men continue to be more at risk of a DRD than women (69% compared with 31% of cases in England and Wales in 2013, respectively). Only one in five poisonings reported to the National Poisons Information Service (NPIS) in 2013–2014, including illicit drug overdose, were reported as being intentional[1]

.

Groups identified as being at high-risk for illicit drug overdose include:

- Injecting drug misusers (especially during first use of opioids and opioid misusers who have HIV or liver disease);

- Multiple drug misusers (especially when sedatives are used in combination with opioids or benzodiazepines);

- Alcohol misusers (supplementary effect with opioids or benzodiazepines and formation of coca-ethylene with cocaine);

- Male sex;

- People dependent on opioids;

- People with reduced tolerance to opioids (e.g. those released from prison, discharged from inpatient or residential detoxification, or have stopped dependent opioid use);

- Drug users who use on their own (fatal overdose risk increased).

An ambulance should be called in all cases of suspected overdose.

Prevalence of drug misuse in the UK

In 2013–2014, one in 11 adults aged 16–59 years had taken an illegal drug in the past year in England and Wales, and around 11.2 million adults were estimated to have used an illicit drug in their lifetime[2]

. Prevalence rates were similar in Scotland, where 8.5% of the population had used an illicit drug in 2012–2013[3]

. In Northern Ireland, the prevalence of illicit drug use in 2010–2011 was 6.6%[4]

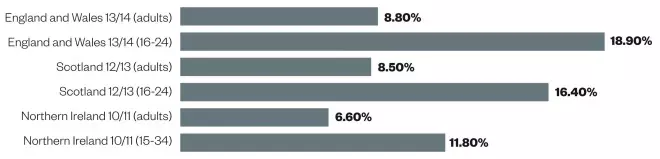

. In all areas of the UK, young people were around twice as likely to have used an illicit drug in the past year compared with all adults (figure 1).

Figure 1: Illicit drug use in the past year in England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland

Opioids

Worldwide, there are an estimated 69,000 deaths a year from opioid overdose. Non-fatal overdose is around 23 times more common[5]

. Injecting drug users (IDUs) are at an elevated risk of overdose, in addition to opioid naïve and polydrug users.

Opioid overdose has a well-recognised clinical presentation with a clearly defined management strategy. Patients experiencing severe opioid toxicity will present with:

- Central nervous system (CNS) depression (e.g. drowsiness, stupor, slow to respond)

- Respiratory depression (shallow breathing)

- Pinpoint pupils

- Hypotension

- Bradycardia.

Milder opioid toxicity can produce a variety of other symptoms. In addition to a less severe presentation of the symptoms mentioned above, these may include gastrointestinal upset, sweating or runny nose or tearing, anxiety, agitation, tremor, bone or joint aches, euphoria, dysphoria, depression, paranoia and hallucinations.

The effects of any opioid overdose may also be potentiated by the simultaneous ingestion of alcohol or other CNS depressants, particularly benzodiazepines. In 2003 in London, 82% of the DRDs where heroin was implicated also involved alcohol or benzodiazepines[6]

.

Naloxone can often be used to prevent death caused by opioid overdose. It is a very safe drug, with the only known contraindication listed as hypersensitivity.

Naloxone can be administered by any person in an emergency for the purpose of saving life. Access to naloxone is critical in preventing opioid-induced deaths and a number of national and international bodies support its widespread distribution to patients and other people who may witness opioid overdoses[7],[8]

.

Naloxone is administered intramuscularly at an initial dose of 400µg; if there is no response after one minute, the patient can be given a further 800µg. If there is still no response after another minute, a further 800µg dose should be given. If there is still no response, the patient can be given a 2mg dose (4mg for seriously poisoned patients). If there is still no response, the diagnosis of opioid-induced toxicity should be questioned.

For children aged under 12 years, a dose of 100µg/kg should be given (maximum 2mg), repeated at intervals of one minute to a maximum dose of 2mg.

Naloxone intravenous infusion tends to only be used in hospitals in cases where an opioid with a long half-life has been ingested (e.g. methadone), and treatment requires a sustained antagonist effect. Patients who have taken an overdose of methadone or illicit opiates also require a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) and continuous cardiac monitoring, liver function tests (LFTs) and a urine toxicology screen. Arterial blood gases (ABGs) should also be assessed for patients who have taken methadone if respiratory depression or hypoxia is suspected[9]

.

Monitoring of overdose patients

The National Poisons Information Service (NPIS) recommends the following steps are taken for all cases of overdose:

- Ensure a clear airway and adequate ventilation is in place if consciousness is impaired;

- Every four hours (may need to be more frequent if patient is symptomatic) record the patient’s temperature, pulse and respiratory rate (TPR), blood pressure, oxygen saturation levels (SaO2) and perform a consciousness assessment;

- Measure creatinine and urea and electrolyte (U&E) levels9.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are often non-toxic when taken alone. However, a synergistic effect occurs when benzodiazepines are mixed with other CNS depressants. There is now a strong body of evidence that benzodiazepines increase the risk of fatal overdose in heroin users and patients on opioid substitution therapy[10]

.

The primary toxic effect of benzodiazepine overdose is CNS depression. Patients present with drowsiness, ataxia, dysarthria and nystagmus. Severe overdose can also cause rhabdomyolysis and hypothermia.

Coma, hypotension, bradycardia and respiratory depression occasionally occur but are seldom serious if the drug is taken alone; respiratory depression can be more serious in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Flumazenil is a benzodiazepine antagonist that is used to treat overdose when only benzodiazepines are involved (unlicensed indication). The summary of product characteristics for flumazenil states caution is necessary in mixed-drug overdose, especially when cyclic antidepressants are involved. This is because certain toxic effects such as convulsions and cardiac arrhythmias that are caused by these antidepressants emerge less readily with concurrent administration of benzodiazepines and, therefore, may be exacerbated with its administration[11]

.

Flumazenil has a half-life of around one hour, and an infusion may be required. The recommended initial dose of flumazenil is 0.3mg intravenously. If the desired level of consciousness is not obtained within 60 seconds, a repeat dose of 0.1mg intravenously may be administered. If necessary, this may be repeated at 60-second intervals up to a total dose of 2mg.

If drowsiness recurs, a second bolus injection of flumazenil may be administered. An intravenous infusion of 0.1–0.4mg per hour can be used. The dosage and the rate of infusion should be adjusted individually.

If no clear effect on awareness and respiration is obtained after repeated dosing, it should be considered that the intoxication is not due to benzodiazepines.

Infusion should be discontinued every six hours to verify whether resedation occurs.

Contraindications include hypersensitivity to the active ingredient or excipients and administration in patients who have been given a benzodiazepine for a potentially life-threatening condition.

Although the benefit of activated charcoal as a gastric decontamination treatment is termed “uncertain” by Toxbase, it is still considered a potential intervention. Provided the patient presents within one hour of ingestion of a toxic dose and the airway can be protected, a charcoal dose of 50g for adults or 1g/kg for children can be administered.

Amfetamine-related substances

Amfetamine-related overdoses include the use of MDMA (ecstasy), methamfetamine (crystal meth) and NSPs, which are often the active ingredients in ‘legal highs’. Legal highs are often regarded as safer than illicit drugs by their users, and a national survey in England found that 20–40% of young people have tried NPSs[12]

.

Toxic effects of NPSs will be based on the individual drug and its contents and purity which are often unknown. The range of NPSs is constantly changing and they are supplied with varying purity levels and contents[12]

, meaning it is often difficult to identify NPSs and treat overdoses.

The pan-European ReDNet project provides a registered text mail service to support clinicians in managing the difficult task of identification and treatment of overdoses with NPSs[12]

.

Amfetamine-like psychostimulants may cause euphoria, increased alertness and an intensification of emotions and self-esteem. Other adverse effects include tremor, sweating, dilated pupils, agitation, confusion, anxiety, vomiting, abdominal pain, seizures, hallucinations or delusions, together with cardiovascular symptoms such as chest pain, palpitations, hypertension and tachycardia.

In severe cases, stroke, myocardial infarction, severe hyponatremia, rhabdomyolysis and renal failure may occur. Serotonin syndrome may also occur, especially if the NPS is taken with other legal or illicit drugs that may contribute to an increased serotonergic burden (see ‘Serotonin syndrome’).

Serotonin syndrome

Serotonin syndrome can result from patients taking two or more drugs that increase the levels of serotonin in serotonergic synapses (e.g. selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors, serotonin and noradrenaline re-uptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, tramadol, triptans and stimulant drugs of misuse).

Patients will present with central nervous system effects (including agitation or coma), autonomic instability (including hyperpyrexia) and neuromuscular excitability (including clonus and raised serum creatine kinase levels).

The management of serotonin syndrome includes stopping all potentially offending drugs, monitoring urea, electrolytes and chronic kidney disease, and treating agitation and delirium.

Death is normally caused by hyperpyrexia-induced multi-organ failure. It is therefore important to rapidly lower the patient’s temperature if it is higher than 39 degrees centigrade.

There is no specific antidote for amfetamine-related substances and novel psychoactive substances. Treatment is based on the presenting symptoms.

In addition to general monitoring (see ‘Monitoring of overdose patients’), cardiac rhythm and body temperature should be monitored at least every 30 minutes. A 12-lead ECG should be performed and repeated as needed, especially in symptomatic patients. LFTs and measurements of creatine kinase (CK) levels and international normalised ratio (INR) should be carried out if signs and symptoms of toxicity are present.

Agitation in adults can be managed with oral or intravenous diazepam, or haloperidol in elderly patients. Midazolam may also be used in children or young adults. This may be delivered buccally (0.2–0.3mg/kg to a maximum of 10mg) or intravenously (0.05–0.1mg/kg to a maximum dose of 10mg). Intravenous lorazepam (0.01mg/kg) may also be used as an alternative.

Cocaine

Cocaine (powder) was the second most common drug of misuse by adults in England and Wales, after cannabis in 2013–2014. There was a 22% rise in deaths involving cocaine in England and Wales in 2013[13]

. As with most illicit drugs, cutting (diluting) with numerous other products can sometimes create complications with cocaine poisoning. For example, haematological complications have been reported to NPIS associated with the use of contaminated cocaine.

The features of cocaine toxicity may include euphoria, agitation, tachypnoea, sweating, ataxia, dilated pupils, nausea, vomiting, headache, delirium and hallucinations.

Cardiovascular complications are potentially the most serious adverse effects. These may include hypertension, chest pain, myocardial ischemia or infarction, cardiac dysrhythmias, coronary artery dissection, aortic dissection, subarachnoid and intracerebral haemorrhage and cerebral infarction. Patients may also experience convulsions, hyperpyrexia, rhabdomyolysis and serotonin syndrome.

There is no specific antidote for cocaine overdose. Patients should be treated with general supportive measures, including the use of activated charcoal if any amount of cocaine has been ingested in the past hour. Cardiac rhythm (including a 12-lead ECG) and body temperature should also be monitored, in addition to LFTs and CK levels.

Agitation and convulsions can be controlled with diazepam (or lorazepam for convulsions) or phenothiazines; haloperidol and droperidol should be avoided as they may lower the threshold for convulsions and may worsen hyperthermia.

Hypertension in agitated adults often settles following the administration of diazepam but, if it persists, intravenous nitrates or calcium antagonists may be administered. Sodium nitroprusside or labetalol are other alternatives.

Ongoing management

All patients who have previously experienced a non-fatal overdose should be given advice on how to reduce the risk of an overdose in the future. This may include education on the risk of injecting drug use or use of multiple drugs, or the effects of combining alcohol and cocaine.

Patients at risk of an opioid overdose can be prescribed naloxone if appropriate, or referred to local schemes. This should be combined with basic life support training for users and their carers[14]

.

If the overdose is deliberate, the patient should receive a psychiatric assessment and be provided with appropriate treatment or signposting.

Local drug services provide a suite of services for drug and alcohol misusers, so a referral to an appropriate service should be considered for all presentations. Patients starting methadone opioid substitution therapy are at increased risk of overdose in the first two weeks of treatment. However, the risk of death significantly decreases for people in treatment (four times less likely to die compared with people not in treatment)[15]

.

Patients who overdose while currently receiving opioid substitution therapy should be referred to their prescriber or care coordinator for an assessment of current treatment.

Graham Parsons BPharm(Hons), PGDip (Comm Pharm), IPresc MRPharmS is a pharmacist with a special interest in substance misuse at Devon Clinical Commissioning Group

References

[1] National Poisons Information Service. National Poisons Information Service Report 2013/14. London: NPIS 2014.

[2] Home Office. Drug misuse: Findings from the 2013/14 crime survey for England and Wales. London: Stationary Office 2014.

[3] Robertson, L. 2012/12 Scottish crime and justice survey: drug use. Edinburgh: Scottish Government 2014.

[4] Regional Drug Task Force (Ireland) and health and Social Care Trust (Northern Ireland). Drugs use in Ireland and Northern Ireland: bulletin 2. Belfast: DHSSPSNI 2012.

[5] World Health Organization. Community management of opioid overdose. Geneva: WHO 2014.

[6] National Treatment Agency. A taxonomy of preventability of overdose death: a multi-method study. London: NTA 2007.

[7] Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Consideration of naloxone. London: ACMD 2012.

[8] Public Health England. Take-home naloxone for opioid overdose in people who use drugs. London: PHE 2015.

[9] National Poisons Information Service. Guide to observations and investigations for the toxicology patient. London: NPIS 2010.

[10] Ford C & Law F. Guidance for the use and reduction of misuse of benzodiazepines and other hypnotics and anxiolytics in general practice. London: SMMGP 2014.

[11] Electronic Medicines Compendium. Flumazenil 0.1mg/ml solution for injection: Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC). 2015.

[12] Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Consideration of the novel psychoactive substances (“legal highs”). London: ACMD 2011.

[13] Office for National Statistics. Deaths related to drug poisoning in England and Wales, 2013. London: ONS 2014.

[14] National Treatment Agency. The NTA overdose and naloxone training programme for families and carers. London: NTA 2011.

[15] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence. London: NICE 2007.

You might also be interested in…

Voice of the Voiceless: co-produced materials to help reduce stigma for people receiving opioid substitution treatment in pharmacies

PJ view: The government’s approach to illegal street drugs should focus on treatment and prevention