This content was published in 2005. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

Insomnia is a subjective complaint of an inability to obtain adequate sleep. It is characterised by difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep or waking up too early in the morning. It is claimed that some form of chronic insomnia affects more than 20 per cent of us at some time in our lives and pharmacists are commonly asked by sufferers for advice and over-the-counter remedies.

What is insomnia?

“Normal sleep” has not been defined and the amount of sleep that an adult needs to function effectively can range from four to nine hours a night. So insomnia needs to be distinguished from short but healthy sleep by looking for adverse effects, such as impaired daytime functioning and irritability.

Insomnia can be indicated if an individual reports two or more of the following:

- Taking more than 30 minutes to fall asleep

- Difficulty in maintaining sleep — waking up for more than 30 minutes during the night and having a sleep efficiency (ratio of time asleep to time spent in bed) of less than 85 per cent

- Having sleep disturbed more than three nights a week

- Significant impairment of daytime functioning (eg, fatigue, mood disturbances) due to lack of sleep

The duration of insomnia is the most important guide to treatment. Currently, insomnia is classified into three types — transient, short-term and chronic:

- Transient insomnia lasts two or three days and is typically due to extraneous factors (eg, jet lag, shift work, noise — see PJ, 12 February, pp187–90)

- Short-term insomnia lasts up to three weeks and is typically due to emotional trauma or physical illness

- Chronic insomnia can be defined as insomnia on most nights, for three weeks or more (common causes are psychiatric disorders, or drug or alcohol misuse)

Identify knowledge gaps

- What non-drug advice would you offer someone having difficulty sleeping?

- How and when should hypnotics be prescribed for insomnia?

- List three prescription-only medicines that have the potential to disrupt sleep.

Before reading on, think about how this article mayhelp you to do your job better. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s areas of competence for pharmacists are listed in “Plan and record”, (available at: www.rpsgb.org/education). This article relates to “appropriate management of common symptoms” (see appendix 4 of “Plan and record”).

Underlying causes of insomnia

Insomnia commonly occurs secondary to an underlying psychiatric or medical condition or unsatisfactory environmental conditions (such as noise or uncomfortable temperature). For example, a recent survey of more than 2,000 people by PruHealth revealed that four in 10 people suffer sleepless nights worrying about their work or home life. These potential causes need to be addressed before considering specific treatment for insomnia.

One US study found that in a group of patients complaining of insomnia, 30 per cent had been diagnosed with depression, 20 per cent suffered other mental illness and 19 per cent had an organic medical condition — thus only 31 per cent were found to have primary insomnia (that is insomnia where no cause can be identified).1

Pharmacists need to know which drugs have the potential to disrupt sleep, and when discussing sleep problems with a patient finding out about any concurrent medication is crucial. Panel 1 shows the “five P” approach to possible secondary causes of insomnia. Drugs known to disrupt sleep are listed in Panel 2.

Panel 1: The “five P” approach to common causes of insomnia

- Physical (eg, cardiovascular disease, apnoea, asthma, tinnitus, pain, restless legs syndrome, nocturia, perimenopausal hot flushes)

- Physiological (eg, late heavy meals that are high in fat or protein or both, late night exercise, noise, shift work)

- Psychological (eg, stress, tension, grief, abnormal concern about sleeping)

- Psychiatric (eg, anxiety, depression, mania, dementia)

- Pharmacological (eg, caffeine, alcohol, nicotine, medicines)

Panel 2: Drugs that can disrupt sleep

- Some anticonvulsants (eg, phenytoin, lamotrigine)

- Beta-blockers (eg, acebutolol, atenolol, metoprolol, oxprenolol, propranolol, sotalol)

- Antiparkinson drugs (eg, amantadine, levodopa)

- Calcium channel blockers (eg, verapamil, diltiazem)

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (eg, citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline)

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (eg, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, isocarboxazid)

- Decongestants (eg, pseudoephedrine, phenylephrine)

- Corticosteroids (eg, cortisone, dexamethasone, prednisolone, triamcinolone)

- Non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (eg, indometacin, diclofenac, naproxen, sulindac, diflunisal)

- Antipsychotics (eg, chlorpromazine, sulpiride)

- Theophylline

- Levothyroxine (in excessive doses)

- Clomifene

- Sulfasalazine

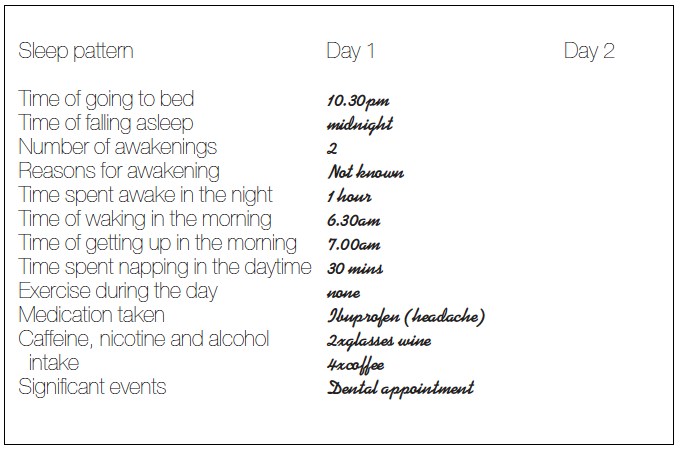

Sleep diaries

To help people with sleep disorders understand their own pattern of sleeplessness (and to help pharmacists or GPs understand an individual’s symptoms), it is valuable for a sleep diary to be kept over one or two weeks. An example of a sleep diary entry is given in Figure 1. However, the patient should not become all-consumed with the fine detail of their sleeping-waking pattern, because this can cause anxiety. In the example, the patient achieves six hours sleep in 24 hours. For many adults, this is sufficient to function effectively, so the next question is: is this patient functioning effectively? The sleep diary also shows that the patient took more than 30 minutes to fall asleep, woke up and stayed awake for more than 30 minutes during the night and has a sleep efficiency ratio of 65 per cent (although the pattern over a longer period should be studied).

The next step is usually to identify what aspect of the insomnia is most troublesome for the patient. A person’s belief about how much sleep he or she needs can also be significant and pharmacists can make sure that this belief is reasonable.

Management of insomnia

Having attended to contributing factors, insomnia can be managed in two ways:

- Non-pharmacologically (changing life-style to include good sleep hygiene, relaxation techniques and day-time exercise)

- Pharmacologically (but drug treatment should be short-term)

In the example given in Figure 1, the first step could be to address the pharmacological factors that may be contributing to the insomnia (ie, alcohol and caffeine).

Adopting good sleep hygiene measuresand following a strict routine for sleeping and getting up can greatly improve sleep. Panel 3 lists recommendations for good sleeping habits. Psychotherapy can also behelpful if anxiety or stress are contributing factors.

Panel 3: Recommendations for good sleep hygiene

DO:

- Go to bed at the same time each day

- Get up at the same time each day (set the alarm and get up, even if you did not fall asleep until late)

- Exercise daily but, preferably, not within four hours of going to bed

- Go outside for at least half an hour each day (especially late afternoon) — exposure to natural light helps restore circadian rhythm

- Keep your bedroom dark, quiet (use earplugs if necessary) and at a comfortable temperature

- Use bed only for rest, sleep or intimacy

- Get into a regular bedtime routine (eg, take awarm bath, read, have a warm milk-based drink — milk contains tryptophan, a precursor to serotonin, which aids sleep — and then go to bed)

- Keep feet warm in bed — wear socks if necessary

DON’T:

- Exercise or take part in stimulating mental activity just before bedtime

- Take stimulants (tea, coffee, chocolate) after late afternoon

- Smoke — nicotine withdrawal can wake you in the small hours

- Drink alcohol –— although it helps you to go to sleep, you are more likely to wake in the night or early morning

- Watch television in bed

- Eat a large (especially fatty) late evening meal — this can make you feel drowsy but its digestion can keep you awake. An empty stomach, on the other hand, can make you toss and turn. A light carbohydrate-rich snack in the evening is best.

- Take daytime or evening naps — naps count towards your total 24-hour need for sleep

- Worry about sleeping (or not sleeping) — this increases anxiety and stress

- Lie awake — if you are awake for more than 30 minutes, get up, go into another room (preferably dimly lit), do something not mentally stimulating or physical and then go back to bed when you feel tired

One non-drug strategy sometimes used toincrease the sleep efficiency ratio is to apply asleep restriction programme that decreases the time spent in bed. For the first few nights of the programme, the number of hours allowed in bed is equal to the average total sleep time per night over the previous week. When sleep efficiency reaches an average of 85 per cent over several nights, the time spent in bed can be slowly increased in 15 minute increments.4

Pharmacological management

Before drug use, the risks versus benefits of treatment for the individual should be weighed up. Drug treatment of insomnia should be reserved solely for transient and short-term cases. For transient insomnia only one or two doses should be given. For short-term insomnia, treatment should not exceed three weeks (ideally only one week) and intermittent dosing is desirable. Hypnotics should not be prescribed for chronic use. The principles of pharmacotherapy for insomnia are listed in Panel 4.

Panel 4: Principles of pharmacological therapy for insomnia

- Only use products known to be efficacious and safe

- Use the lowest dose for the shortest time and aim for intermittent dosing because tolerance and dependance are more likely to develop with continuous dosing

- If a hypnotic is used for a prolonged period (ie, more than three weeks) or the dose is high, it must be withdrawn gradually

Prescription-only medicine options

There is no ideal hypnotic on the market but according to guidance from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence, an efficacious hypnotic with the lowest cost should be prescribed (ie, a benzodiazepine). The newer “Z drugs” (see below) may be given where a benzodiazepine is unsuitable (eg, where the patient is elderly) or poorly tolerated. If a patient has not responded to one prescription hypnotic, another should not be tried.

Hypnotic prescribing in the elderly should be avoided. These patients are at particular risk of becoming ataxic and confused and are, therefore, at risk of injury through falls. In addition, many elderly people need to go to the toilet during the night when they are still under the influence of a hypnotic. Residual effects the next day are also more prevalent in elderly patients.

Benzodiazepines

All benzodiazepines have both anxiolytic and hypnotic effects and their use is determined by their duration of action (half-life). They enhance the effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) by binding to their own benzodiazepine receptor sites on the GABA receptor. This boosts GABA’s inhibitory action and reduces the output of excitatory neurotransmitters such as noradrenaline, serotonin and dopamine. For insomnia, the shorter-acting benzodiazepines (eg, loprazolam, lormetazepam and temazepam) are recommended because those with a longer half-life (eg, nitrazepam, flunitrazepam and flurazepam) are associated with increased hangover-like effects.

The use of benzodiazepines to treat insomnia has been controversial for years and although use has declined, they are still prescribed, sometimes for long periods. In the year 2002–03, in England, 12.7 million prescriptions for benzodiazepines were written by GPs and 30 per cent of these were for 56 tablets.2 Pharmacists can work with GPs, to encourage patients to stop taking benzodiazepines and support them through tailored withdrawal programmes. Advice from theCommittee on Safety of Medicines is that benzodiazepines should only be used to treat insomnia when the condition is “severe, disabling or subjecting the individual to extreme stress”.

Physical and psychological dependence, tolerance to and difficulty withdrawing from a benzodiazepine, can occur after less than 14 days’ continuous use. Withdrawal symptoms can manifest themselves anytime from a few hours to three weeks after stopping a benzodiazepine, depending on the drug’s half-life.

Z drugs

Z drugs (zopiclone, zolpidem and zalepon) are structurally unrelated to the benzodiazepines and to each other. However, their effects are similar. Although originally claimed to produce fewer side effects and to have a decreased tendency for tolerance and dependence, these claims have not been substantiated.

Zopiclone has similar effects to the benzodiazepines and also has the potential to cause hangover and impaired psychomotor performance. Tolerance, dependence and misuse have been reported. Zolpidem has similar effects but is shorter acting than zopiclone and has minimal hangover effects. It also appears to have reduced potential for tolerance, dependence and abuse. Zaleplon has an even shorter duration of action and so is only indicated where there is difficulty in falling asleep. It has little effect on sleep duration. Zaleplon is useful because it does not need to be taken in anticipation, ie, it can be taken when the patient is having difficulty sleeping. It appears to have reduced potential for dependence and abuse and is less likely to cause rebound insomnia when stopped.

Other prescription-only medicines

A variety of drugs with sedative properties have been used to treat insomnia. However, only the benzodiazepines and Z drugs are currently recommended.

Barbiturates

Barbiturates are only used in severe intractable insomnia where the patient has been taking the barbiturate for a long time. Their safety profiles and adverse effects are unacceptable.

Chloral and derivatives

Choral hydrate and its derivatives have a limited role in childrenon the rare occasion that a hypnotic is used for night-terrors or sleep-walking. They are also sometimes used in the elderly, but limited by high incidence of gastric irritation.

Chlormethiazole

Chlormethiazole can be used in the elderly since its effects do not continue the next day and it has less potential to cause confusion. However, like chloral hydrate, it is associated with gastric irritation.

Hypnotic withdrawal

The National Service Framework for Mental Health states that, where possible, chronic users of hypnotics should be encouraged and helped to stop taking them. Evidence suggests that 40 per cent of chronic users can withdraw without difficulty, 40 per cent can withdraw with difficulty and 20 per cent do not want to withdraw.

OTC options

There are a number of OTC options available to the pharmacist treating a patient with insomnia. Little evidence as to efficacy exists for the majority of these preparations. Only those backed up with some clinical research are mentioned here.

Herbal products

Some studies have shown that valerian acts as a mild sedative, improving subjective experiences of sleep when taken for one or two weeks. In contrast, a review of the scientific literature for randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of valerian’s hypnotic use (by the Department ofComplementary Medicine, University of Exeter) was inconclusive.3

Valerian is an option for OTC management of insomnia after sleep hygiene measures have been initiated. It should not be used alongside conventional drug treatment for insomnia or by pregnant or breast-feeding women.

Over-the-counter sedative antihistamines

The sedative antihistamine preparations available to the public contain either diphenhydramine (Dreemon, Medinex, Nightcalm and Nytol)or promethazine (Phenergan Nightime and Sominex). These preparations tend to cause hangover-like effects and should be avoided in the elderly who are more prone to these side effects.

Diphenhydramine has been shown to reduce symptoms of insomnia in the majority of patients taking it.4 It causes less daytime sedation and has a faster onset of action than promethazine. Neither is known to cause dependence, but diphenhydramine has been reported as the OTC medicine most prone to abuse.9 Manufacturers recommend a 14-day limit for non-prescription use of these products.

Melatonin

There are reports that melatoninmay have some application in treating insomnia, although evidence is lacking and it is unlicensed in the UK.

Action: practice points

The Society will expect to see various approaches in a pharmacist’s CPD portfolio.

- When responding to queries about insomnia or daytime sleepiness, integrate your knowledge of obstructive sleep apnoea and restless legs syndrome (see PJ, 12 February, p187–90) into your questioning strategy.

- Put together a short training session for your staff on insomnia; include sleep hygiene and the merits and drawbacks of relevant OTC products.

- Review your elderly patients’ medication profiles for hypnotic drugs. With the carers and doctors, work out individualised programmes for withdrawal.

Evaluate

For your work to be presented as CPD, you need to evaluate your reading and any other activities. Answer the following questions: What have you learnt? How has it added value to your practice? (Have you applied this learning or had any feedback?) What will you do now and how will this be achieved?

Resources

- Recommendations for benzodiazepine withdrawal are available in the British National Formulary (section 4.1) and at the Prodigy website.

- Prodigy guidance on insomnia and a specimen sleep diary are available at: www.prodigy.nhs.uk/guidance.asp?gt=Insomnia (accessed 13 December 2004).

- Ashton H. Benzodiazepines: how they work and how to withdraw. Available at: www.benzo.org.uk (accessed 12 January 2005).

References

- Holbrook A, Crowther R, Lotter A, Cheng C, King D. The diagnosis and management of insomnia in clinical practice: a practical evidence-based approach. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2000;2:162.

- Warning issued over sleeping pill prescribing. 2004; Available at: www.jbmedical.com/Feb04.html (accessed 12 January 2005)

- Stevinson C, Ernst E. Valerian for insomnia: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Sleep Medicine2000;1:91–9.

- Barrington SL, Carroll R, Hewitson M, Munangatire B, Rogers PJ, Wood SM. Use of diphenhydramine as a non-prescription hypnotic: patients’ experiences. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2003;11 (Suppl):R25.

You might also be interested in…

Insomnia disorder: management strategies

Sleep disorders: treatment