Shutterstock.com

In a previous article ‘Insomnia disorder: diagnosis and prevention

’ (part 1), naturalistic sleep was examined as a physiological process and insomnia was discussed as a pathophysiological disordering of this, influenced by psychiatric, somatic and environmental factors. This article focuses on the clinical management of insomnia, presenting pharmacological and psychological strategies as different, yet not necessarily mutually exclusive, means of treating the disorder. Sleep disturbances have become increasingly common during the COVID-19 pandemic owing to changes in work schedules, travel and exercise routines, as well as the concern and anxiety it may cause in some individuals[1]

. As a frontline profession in the pandemic, it is important that pharmacists understand how sleep disturbances should be managed and how to best counsel patients in this regard.

In general, there is an over-reliance on hypnotics in the treatment of insomnia and it is acknowledged that more could be done to explore sleep disturbances with patients[2]

. When a patient presents with sleep disturbance, there is often pressure on GPs to prescribe the patient a hypnotic agent[2]

. A 2010 study by Siriwardena et al. demonstrated that GPs recognise the risks of hypnotics and are willing to reduce prescribing, but feel they have a lack of resources and non-pharmacological alternatives with which to do so[3]

. Therefore, it is necessary for pharmacists to be able to understand how to manage sleep disturbances before simply referring the patient to their GP.

It is important to remember that the appropriate use of hypnotics is crucial as — when necessitated — these medicines are of therapeutic value. The entire pharmacy team should take care not to label patients who use or request these medicines as ‘drug-seeking’, when they are simply trying to achieve a good night’s sleep.

With that in mind, it is important to understand that there has been a culture shift away from hypnotics and towards cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) as a first-line intervention. Greater awareness of CBT-I among pharmacists can add an evidence-based, non-pharmacological alternative to the available treatment options and may facilitate the reduction of unnecessary hypnotic use[4],[5],[6]

.

By providing CBT-I advice as a first-line treatment option, pharmacists may negate the need for a hypnotic prescription, reduce drug spend, prevent side effects from medicines and potentially improve treatment outcomes[4],[5],[6]

.

This article aims to aid pharmacists’ management of patients with insomnia, utilising the available pharmacological and non-pharmacological options. It also provides a framework that pharmacists can use to embed concepts of CBT-I into their practice. Before initiating treatment in insomnia, it is crucial to determine its nature[7]

.

Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia

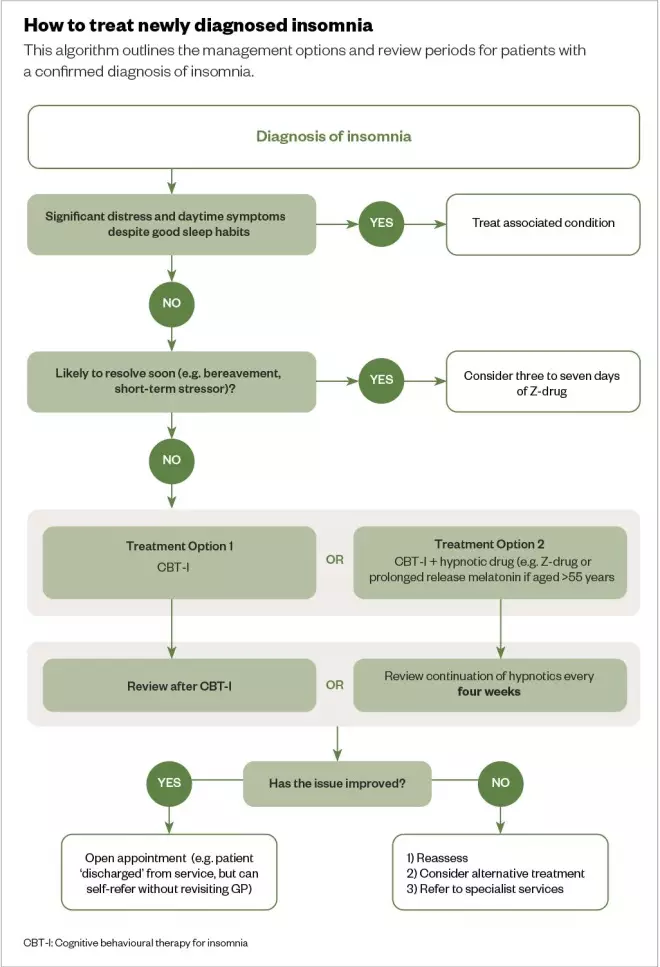

All patients living with insomnia should be offered CBT-I-related advice about sleep, with a clinical judgement made in parallel, regarding the need for hypnotics (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: How to treat newly diagnosed insomnia

Z-drug: zolpidem and zopiclone

Source: Adapted from J Psychopharm

[8]

CBT-I is the first-line treatment for chronic insomnia, as recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the British Association for Psychopharmacology[8],[9],[10],[11]

. The effectiveness of CBT-I alone in treating long-term insomnia is superior to that of hypnotics in isolation, but the best treatment outcomes are typically seen when both are used in combination[12],[13]

.

Treatment usually consists of four to eight sessions, with an average is six sessions, once per week[12],[13],[14]

. These can be face-to-face, over-the-phone or online, using a website or app, and can be delivered individually or in group settings[14]

. High success rates have been reported from these sessions[15]

. There are five techniques — four behavioural and one cognitive — promoted as part of CBT-I, that aim to help patients manage their condition long-term:

1. Sleep education and hygiene

The first technique involves managing expectations of normal sleep (e.g. night-time waking or decreased sleep need with increased age). Advice focuses on providing information on these potential sleep disruptors:

- Diet (e.g. avoiding large meals before bedtime);

- Exercise (e.g. avoiding vigorous exercise before bedtime);

- Daily routine (e.g. establishing a consistent bedtime routine, such as brushing teeth, showering and reading);

- Substance use (e.g. avoiding using caffeine, alcohol and nicotine before bedtime);

- Sleep environment (e.g. reducing light, noise and temperature in the bedroom).

2. Stimulus control

This stage aims to reinforce psychological associations between the bed and sleep, breaking psychological associations between the bed and wakefulness. For example, patients are advised that they should only get into bed when sleepy, get out of bed if they are unable to sleep, and to only use the bedroom for sleep, sex and getting dressed[16]

.

3. Psychoeducation and relaxation strategies

Routines, such as progressive muscle relaxation (tensing and releasing different muscle groups) and meditation, can create a wind-down period before bed[17]

. These may be used to relieve body tension and thoughts that could interfere with sleep. Other relaxation strategies could include listening to music, reading or following self-care routines[18]

.

4. Sleep scheduling

This principle focuses on organising sleep, including setting times for waking and getting out of bed, but also highlights the need to go to bed when feeling tired, not at a set time. It is typically carried out by sleep specialists; however, it is simple to do and could be carried out by pharmacists and GPs with an interest in sleep.

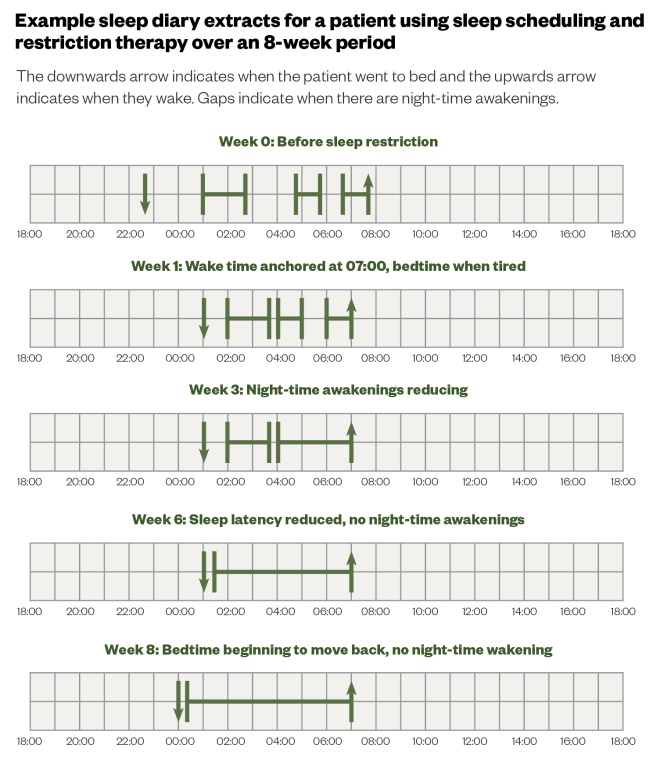

Sleep restriction therapy aims to slightly sleep-deprive the patient in a controlled manner, such that they sleep more effectively during their time in bed[12]

. This works by setting an anchor point to wake up slightly earlier than their normal time and pushing the time to go to sleep back to when the patient feels tired later in the night (e.g. around midnight or 01:00). Over the first few weeks, the patient will feel worse, but sleep efficiency will increase and night-time waking will be reduced. Showing patients the effects and progress through the completion of a sleep diary (see part 1) can be a motivating factor.

As sleep efficiency increases, bedtime can gradually be moved earlier in stages of 15–30 minutes, until a normal night’s sleep is restored. This usually takes up to eight weeks (see Figure 2)[10]

. Sleep should not be restricted below five hours, and sleep restriction should not be recommended in patients who must drive in their line of work, or who have a history of mental illness, seizures, or other sleep disorders (e.g. sleep apnoea). In these patients, sleep compression can be used instead, but this must be used with caution by specialists only[19]

.

Figure 2: Example sleep diary extracts for a patient using sleep scheduling and restriction therapy over an 8-week period

Sleep compression therapy is a milder form of sleep restriction; the only difference is that instead of immediately restricting sleep to a certain time, the time allowed in bed is reduced in 30-minute intervals, until 85% sleep efficiency is reached. The minimum time sleep should be compressed to is 6.5 hours[5],[12],[19]

.

5. Cognitive therapy

Addressing factors perpetuating insomnia, such as routines before bedtime (e.g. vigorous exercise) and discussing paradoxical intention (e.g. the harder you try to fall asleep, the more difficult it becomes to sleep) can also be effective methods to improve sleep[20]

. Patients should be encouraged not to ‘try’ to sleep, in order to destigmatise and manage expectations at bedtime.

Restrictions in accessing CBT-I appear to be based on healthcare professionals’ unfamiliarity with the concept, such as GPs or community mental health teams, who may not readily offer it to patients in preference of traditional pharmacological treatments[21]

.

Historically, the practice of CBT-I by healthcare professionals has been limited, although this is changing as the complexity of the intervention is being optimised[22]

. It can now be delivered in a wide variety of environments, including consultation rooms or as over-the-counter brief interventions. It is possible for pharmacists to begin to deliver CBT-I interventions within their practice, for example, by upskilling themselves and training their teams to deliver CBT-I in the pharmacy, consultation space or by creating routine CBT-I clinics for patients to self-refer.

Pharmacist-led CBT-I may not necessarily be in the same format of the structured sessions delivered by specialists. Interventions containing CBT-I concepts delivered at opportunistic moments within the pharmacy, or as structured sessions led by the pharmacist, have the potential to affect the care of patients with insomnia and may reduce the inappropriate use of hypnotics.

Explaining sleep habits and hygiene may be effective in treating mild, short-term insomnia (see Box)[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34]

. If these have been tried and significant distress and daytime symptoms persist, pharmacological treatment should be considered.

Box: Sleep hygiene and healthy lifestyle measures to prevent insomnia

- Doing regular moderate aerobic exercise helps to reduce pre-sleep anxiety. Overall sleep quality evidence varies for duration and frequency of exercise sessions: aim for 3–4 times per week, from 10–50 minutes per session;

- Avoid exercise within four hours of going to bed;

- Avoid nicotine within six hours of bedtime if unable to abstain completely;

- Drink alcohol only within the recommended limits (i.e. a maximum of 14 units per week, spread over 3 or more days) and avoid within 6 hours of bedtime;

- Increase daytime natural light exposure;

- Avoid large meals two hours before bed bedtime;

- Reduce the number of caffeine-containing drinks consumed throughout the day. Consider complete elimination and switch to decaffeinated products or no caffeine after midday;

- Avoid day-time napping and have a wind-down hour prior to bedtime. Practice relaxation techniques before bed, such as deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, relaxation tapes or yoga;

- Only use the bedroom for sleep, sex and getting dressed;

- Create a sleep environment in the bedroom — it should be dark and quiet, without a TV, phones or clock, and should be at a comfortable temperature;

- Set a regular waking time seven days per week and only go to bed when feeling sleepy;

- If unable to sleep for what feels like more than 20 minutes, leave the bedroom. Find a comfortable place in the house and try reading, having a light snack (e.g. toasted bread) or doing some quiet activity. Do not attempt alerting activities, such as household chores, office work, watching television, using your mobile phone or using a computer, but try to find something relaxing you can enjoy. Only return to bed when you feel sleepy. If you are still not sleeping after 20 minutes, get up again until you feel sleepy;

- Avoid clock-watching to see how long you have been awake. Turn the clock to face the other way.

Sources:Ger Med Sci

[23]

, Br J Gen Pract

[24]

, Hospital for Special Surgery[25]

, Cochrane Database Syst Rev

[26]

, BNF

[27]

, Eur J Clin Pharmacol

[28]

, Physiol Behav

[29]

, Drugs

[30]

, Proceedings of UCLA Healthcare

[31]

, Cochrane Database Syst Rev

[32]

, Br J Psychiatry

[33]

, Psychiatric News[34]

If the insomnia is caused by short-term stressors and is resolved quickly, a short course of ‘Z-drugs’ (e.g. zopiclone) for three to seven days should be considered. Hypnotics are effective in the treatment of short-term insomnia and provide symptomatic relief, but are only licensed for short-term use.

In practice, these medicines are often continued beyond the course of their license and, on cessation, patients may return to troubled sleep states. Evidence shows behavioural treatment (i.e. CBT-I) is equally effective when compared with hypnotics in short-term treatment of insomnia symptoms[8]

. This approach is preferred over hypnotics for maintaining sleep improvement[35]

. Indeed, there is some evidence that the best treatment option for insomnia is a course of CBT-I in combination with a course of hypnotics[35]

. This can potentially lead to reduced prescribing of hypnotic medicines.

However, CBT-I is not suitable for everyone — for example, it may not be appropriate for patients struggling with severe insomnia, who cannot engage in talking therapies, such as those with an acute episode of mania or psychosis, as sleep deprivation can worsen outcomes in manic relapse or an episode of psychosis[36]

. Figure 1 outlines how newly diagnosed insomnia should be treated[8]

.

Patients who are already taking hypnotics, who start to experience further sleep disturbances, should have CBT-I alongside the existing hypnotic prescription[9],[37]

. However, it should not be used to replace it. As sleep efficiency increases past the normal threshold of around 85%, the hypnotic dose can be reduced (see part 1). This can be repeated until the hypnotic has been completely withdrawn[9]

.

CBT-I should be offered as first-line treatment for long-term insomnia disorder[8]

. If this is ineffective or unavailable, or the patient urgently requires immediate improvement in their sleep, hypnotics should be offered alongside CBT-I. The patient should be reviewed after CBT-I is complete, or every four weeks if using hypnotics.

Pharmacotherapy

The brain’s arousal system is governed by activating neurotransmitters (e.g. norepinephrine, serotonin, acetylcholine, dopamine, histamine, glutamate and orexin), which promote wakefulness, and sedating/inhibitory neurotransmitters (e.g. gamma-Aminobutyric acid [GABA] and adenosine), which promote sleep[38]

.

These two groups of neurotransmitters form the basis of hypnotic medicines, such as benzodiazepine and Z-drugs[38]

. Pharmacists should understand how these medicines work and be able to effectively counsel patients on their use.

Benzodiazepines and Z-drugs

Both benzodiazepines and Z-drugs increase the effect of neurotransmitter GABA at GABA-A receptors, making them GABA positive allosteric modulators (GABA-PAMs). This gives rise to their hypnotic, anxiolytic, muscle relaxant and anticonvulsant properties[39]

.

Temazepam — a benzodiazepine — is useful for acute episodes of insomnia (at a starting dose of 10mg before bed)[40]

. However, in bereavement, benzodiazepines may cause emotional blunting owing to the inhibition of psychological adjustment, which can prevent the grieving process, although the evidence for this is conflicting[40],[41],[42]

.

The Z-drugs zopiclone (starting dose of 7.5mg once-daily) and zolpidem (starting dose of 10mg once-daily) are similarly useful for short-term treatment[43],[44]

. Zolpidem has a shorter half-life than zopiclone, making it less effective in insomnia where sleep maintenance is problematic. However, it is less likely to cause a ‘hangover effect’ (i.e. the feeling of sedation the day following a dose of a hypnotic)[45]

. Z-drugs generally have a more acceptable side effect profile than benzodiazepines[46]

.

Long-term use of GABA-PAMs has been known to increase anxiety and falls risk, and worsen sleep and depression owing to their hypnotic effect[42]

. The hypnotic effect of these drugs comes from their ability to enhance the sleep-inducing effect of GABA at GABA-A receptor sites in the brain[8]

. Agents with longer half-lives, such as flurazepam, nitrazepam and diazepam are more likely to cause this, making them inappropriate for treatment of insomnia disorder[47]

.

Owing to the potential for overuse — which may lead to addiction and dependence — NICE recommends that GABA-PAMs should be used for the shortest duration possible, at the lowest dose that controls symptoms[48]

. However, there is an emerging body of evidence that shows the dependence potential of GABA-PAMs may have been overestimated, particularly for Z-drugs[8]

. An increase in sleep latency (i.e. how long it takes to get to sleep) that resolves over a matter of days during GABA-PAM withdrawal, has also been reported, which may reduce patient satisfaction when using these products[49]

. The addictive nature of these products supports the use of CBT-I during withdrawal[8]

.

A study by Hoffmann found that pharmacists have a critical view of Z-drugs, especially concerning their associated side effects. However, they also perceive more often than GPs that the benefits outweigh harms in younger and older patients using benzodiazepines[23]

.

Epidemiological data show an increased risk of road traffic accidents, fractures and falls in patients who use benzodiazepines, with further work needed to identify risks relating to the development of other illnesses, such as dementia[50]

. It is important that pharmacists counsel patients regarding driving legislation (e.g. “Do not drive or operate heavy machinery”) in relation to sedating drugs, especially considering the frequent use of these products outside of licensed indications[24]

. Pharmacists should also ask questions to help understand a patients risk of falling (e.g. “Do you ever feel unsteady on your feet?” and “Do you feel lightheaded or dizzy after you take your medicine?”)[25]

.

Melatonin

As light levels diminish, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (which controls circadian rhythms) ceases its inhibitory control of the pineal gland. In response to this darkness, the pineal gland causes a rise in the endogenous hormone melatonin. Once released, melatonin binds to the MT1 and MT2 receptors in the hypothalamus, creating the feeling of sleepiness and resynchronising the circadian clock (see part 1)[7]

.

Decreases in endogenous melatonin production during ageing can precipitate sleep problems. In addition, endogenous melatonin secretion has been found to become dysregulated in intensive care patients. There is some evidence that exogenous melatonin can be useful in correcting the circadian rhythm to reinstate a normal sleep-wake cycle, although a Cochrane review stated that this evidence is of very low quality[26]

.

Both immediate and sustained release exogenous melatonin formulations could act by increasing the levels of endogenous melatonin in circulation to regulate circadian rhythm and sleep-wake cycles[9]

. The use of melatonin (a starting dose of 2mg once-daily) for insomnia is not routinely recommended, although it is licensed for short-term treatment (up to 13 weeks) of insomnia in patients aged over 55 years[48]

. Counselling points vary between formulations, with immediate-release formulations taken on an empty stomach and modified-release formulations taken with food[27]

.

Beta blockers and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit the secretion of endogenous melatonin, which can sometimes lead to sleep disturbances. Patients prescribed these medicines may, therefore, benefit from the use of melatonin[28],[29]

.

Antidepressants

This class of medicines has a range of receptor binding profiles and those currently licensed in the UK for use in treating depression are rooted in the science of the monoamine hypothesis of depression[8]

. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) can be stimulating and, consequently, worsen insomnia. Patients should be counselled to take these antidepressants in the morning[30]

.

Other antidepressants, such as the sedative antidepressants amitriptyline and low-dose mirtazapine (i.e. 15mg once-daily) have an antihistamine effect and can create a feeling of drowsiness[30]

. In practice, these are often given at night to assist with sleep onset, although at higher doses (i.e. above 30mg) mirtazapine becomes less sedating[31]

. However, at higher doses, the norepinephrine effects may also interfere with sleep. In such cases, switching the administration from bedtime to the morning can be enough to correct a patient’s insomnia.

Amitriptyline is not licensed for insomnia and a 2018 Cochrane review found there to be no evidence to support its use[32]

. Despite this, and a considerable side-effect profile, it is the third most preferred intervention for the treatment of insomnia by GPs[2]

. Sedative antidepressants are also more likely to be lethal in overdose than GABA-PAMs. Therefore, this practice is not founded in evidence and may be dangerous[33]

.

Antidepressants could, however, be considered where there is a comorbidity with depression or anxiety[30]

. In order to achieve the greatest clinical outcome for patients where this is the case, both the mental health condition and insomnia diagnosis should be targeted for treatment[34]

. If pharmacists identify the inappropriate use of sedative antidepressants to treat insomnia, they should discuss this with the patient and attempt to speak to the prescriber to request a review of the prescription within four weeks, to recommend alternative therapies to improve sleep (such as CBT-I).

Sedating antihistamines

These act to reduce histamine function, but are not selective for histamine. They can also cause side effects, including dizziness, dry mouth, headache, hypotension, urinary retention and blurred vision owing to their anticholinergic activity[51]

. Anticholinergic side effects are particularly problematic in older people as they have an increased risk of falling, which makes sedating antihistamines dangerous in overdose[33]

.

Diphenhydramine and promethazine can both be used to cause sedation and promote sleep in patients with short-term insomnia. However, these older antihistamines have some abuse potential as they potentiate the high obtained when used in conjunction with opiates[52]

.

Over-the-counter (OTC) options for the treatments are limited to sedating antihistamines; however, their use may mask symptoms of an underlying sleep disorder. Products containing promethazine or diphenhydramine are only licensed for the symptomatic relief of coughs, colds, chills and influenza, and should not be recommended for the treatment of insomnia[9],[11],[53]

.

Pharmacists should ask open questions (e.g. “How did the symptoms start?”, “Have you tried anything so far?” and “Tell me about your bedtime routine”) and appropriately counsel patients to ensure the safe use of these products, and to rule out other diagnoses or medication-induced sleep disturbances (e.g. “Only use for five nights in a row, with a two-night break between”). OTC products should only be prescribed for diagnosed insomnia that is ‘likely to resolve soon’ and patients seeking these medicines for prolonged periods warrant further investigation of symptoms and referral to a GP for formal diagnosis[54]

.

Ensuring the safe prescribing of hypnotics

Pharmacists have a responsibility to ensure that they do not recommend OTC treatments inappropriately. This can be done by making notes in patients’ records when they purchase sedating antihistamines, and by ensuring all staff provide adequate counselling and advice when selling products at the counter.

In addition, if a pharmacist comes across inappropriate prescribing (e.g. prolonged use of hypnotics) they should speak to both the patient and prescriber to highlight the issues. Communicating with prescribers regarding patient care can be challenging, but pharmacists should aim to be clear, concise and try to recommend solutions, such as alternative treatment options. Pharmacists should provide enough information for the healthcare professional to make an informed decision, such as the name and dose of the medicine in question, the expected duration of use, and the patient’s actual duration of use and why this is problematic.

When recommending alternative treatment options, these should be feasible, acceptable to the patient and communicated clearly (e.g. avoid the very generic phrase “Could you please review”, and be specific, asking “Could you reduce the dose”). Some prescribers may be reluctant to interfere with medicines for sleep started in a different care setting (e.g. if hypnotics are started in secondary care, primary care prescribers may not feel empowered to alter the prescription, or in cases where sedating antihistamines have been prescribed in mental health settings).

Pharmacists, as medicine experts, in all settings must actively involve themselves in the prescribing of pharmacological treatments to manage sleep disorders and promote these alongside non-pharmacological options to optimise patient care.

Useful resources

For more information and resources, including a sleep chart and smarter sleep checklist, visit: www.cntw.nhs.uk/smartersleep

About the authors

Rebecca Richardson is clinical pharmacist at Garden Park Surgery, Howden, UK; Alastair Paterson is clinical pharmacist at Northumbria, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, UK; Adam Rathbone is lecturer in social and clinical pharmacy at Newcastle University, UK; Julia Blagburn is integrated care pharmacist, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, UK and Andy Husband is professor of clinical pharmacy at the school of pharmacy, Newcastle University, UK. Correspondence to: adam.rathbone@newcastle.ac.uk

Financial and conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

References

[1] The Sleep Council. Survey reveals COVID-19 having severe impact on sleep. 2020. Available at: https://sleepcouncil.org.uk/survey-reveals-covid-19-having-severe-impact-on-sleep/ (accessed July 2020)

[2] Everitt H, McDermott L, Leydon G et al. GPs’ management strategies for patients with insomnia: a survey and qualitative interview study. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64(619):e112–e119. doi: 10.3399/bjgp14X677176

[3] Siriwardena AN, Apekey T, Tilling M et al. General practitioners’ preferences for managing insomnia and opportunities for reducing hypnotic prescribing. J Eval Clin Pract 2010;16(4):731–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01186.x

[4] Manber R, Edinger JD, Gress JL et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep 2008;31(4):489–495. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.489

[5] Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK, Radtke RA et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of chronic primary insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;285(14):1856–1864. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.14.1856

[6] Park KM, Kim TH, Kim WJ et al. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia Reduces Hypnotic Prescriptions. Psychiatry Investig 2018;15(5):499–504. doi: 10.30773/pi.2017.11.20

[7] Richardson R, Paterson A, Rathbone AP et al. Insomnia disorder: diagnosis and management. Pharm J 2020;304(7938):398–404. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2020.20208004

[8] Wilson S, Anderson K, Baldwin D et al. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus statement on evidence-based treatment of insomnia, parasomnias and circadian rhythm disorders: an update. J Psychopharm 2019;33(8):923–947. doi: 10.1177/0269881119855343

[9] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Insomnia. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. 2020. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/insomnia (accessed July 2020)

[10] Espie CA. Overcoming insomnia and sleep problems. A self-help guide using Cognitive Behavioural Techniques. 2nd edn. London: Robinson; 2010

[11] Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C et al. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res 2017;26(6):675–700. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12594

[12] Morin CM, Colecchi C, Stone J et al. Behavioral and pharmacological therapies for late-life insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1999;281(11):991–999. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.11.991

[13] Mitchell MD, Gehrman P, Perlis M & Umscheid CA. Comparative effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract 2012;13:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-40

[14] Anderson KN. Insomnia and cognitive behavioural therapy-how to assess your patient and why it should be a standard part of care. J Thorac Dis 2018;10(Suppl 1):S94–S102. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.01.35

[15] Miller C, Espie C & Kyle SD. Cognitive behavioral therapy for the management of poor sleep in insomnia disorder. ChronoPhysiology and Therapy 2014;4:99–107. doi: 10.2147/CPT.S54220

[16] Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust. Sleep Hygiene. 2020. Available at: https://www.guysandstthomas.nhs.uk/resources/patient-information/sleep/Sleep-hygiene.pdf (accessed July 2020)

[17] Bracke PE. Progressive muscle relaxation. In: IB Weiner, WE Craighead (eds.) Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. 4th edn. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. p. 1–2

[18] Hauri PJ. Sleep Hygiene, Relaxation Therapy and Cognitive Interventions. Case Studies in Insomnia Critical Issues in Psychiatry: An Educational Series for Residents and Clinicians. Boston. MA: Springer; 1991.

[19] Lichstein KL, Thomas SJ & McCurry SM. Sleep Compression. In: Perlis M, Aloia M, Kuhn B (eds.) Behavioral Treatments for Sleep Disorders. San Diego: Academic Press; 2011. p. 55–59

[20] Ascher LM & Efran JS. Use of paradoxical intention in a behavioral program for sleep onset insomnia. J Consult Clin Psychol 1978;46(3):547– 550. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.3.547

[21] Davy Z, Middlemass J & Siriwardena AN. Patients’ and clinicians’ experiences and perceptions of the primary care management of insomnia: qualitative study. Health Expect 2015;18(5):1371–1383. doi: 10.1111/hex.12119

[22] Fields BG, Schutte-Rodin S, Perlis ML & Myers M. Master’s-Level practitioners as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia providers: an underutilized resource. J Clin Sleep Med 2013;9(10):1093–1096. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3096

[23] Hoffmann F. Benefits and risks of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs: comparison of perceptions of GPs and community pharmacists in Germany. Ger Med Sci 2013;11:Doc 10. doi: 10.3205/000178

[24] Siriwardena AN, Qureshi MZ, Dyas JV et al. Magic bullets for insomnia? Patients’ use and experiences of newer (Z drugs) versus older (benzodiazepine) hypnotics for sleep problems in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2008;58(551):417–422. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X299290

[25] Jayasinghe N. Addressing falls prevention among older adults. Part II: Approaching your patients. 2011. Available at: https://www.hss.edu/conditions_addressing-falls-prevention-older-adults-approaching.asp (accessed July 2020)

[26] Lewis SR, Pritchard MW, Schofield-Robinson OJet al. Melatonin for the promotion of sleep in adults in the intensive care unit. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;5(5):CD012455. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012455.pub2

[27] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Melatonin. 2020. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/melatonin.html (accessed July 2020)

[28] Stoschitzky K, Sakotnik A, Lercher P et al. Influence of beta-blockers on melatonin release. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1999;55(2):111–115. doi: 10.1007/s002280050604

[29] Murphy PJ, Myers BL & Badia P. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs alter body temperature and suppress melatonin in humans. Physiol Behav 1996;59(1):133–139. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02036-5

[30] Wiegand MH. Antidepressants for the treatment of insomnia: a suitable approach? Drugs 2008;68(17):2411–2417. doi: 10.2165/0003495-200868170-00001

[31] Leonard SD & Karlamangla A. Dose-dependent sedating and stimulating effects of mirtazapine. Proceedings of UCLA Healthcare 2015. 2015. Available at: https://proceedings.med.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Dose-Dependent-Sedating-and-Stimulating-Effects-of-Mirtazapine.pdf (accessed July 2020)

[32] Everitt H, Baldwin DS, Stuart B et al. Antidepressants for insomnia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;5(5):CD010753. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010753.pub2

[33] Wilson S & Nutt D. Management of insomnia: treatments and mechanisms. Br J Psychiatry 2007;191(3):195–197. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036301

[34] Lamberg L. Manual updates sleep disorder diagnoses. 2014. Available at: https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2014.8b20

[35] Rourke E & Anderson KN. Sleep disorders. BMJ 2014;349:g3818. doi: 10.1136/sbmj.g3818

[36] Harvey AG, Kaplan KA & Soehner A. Interventions for sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder. Sleep Med Clin 2015;10(1):101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2014.11.005

[37] O’Regan D. The misprescribing of Z-drugs for insomnia. 2019. Available at: https://www.acnr.co.uk/2019/05/the-misprescribing-of-z-drugs-for-insomnia/ (accessed July 2020)

[38] Brown RE, Basheer R, McKenna JT et al. Control of sleep and wakefulness. Physiol Rev 2012;92(3):1087–1187. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2011

[39] Griffin III CE, Kaye AM, Rivera Bueno F & Kaye AD. Benzodiazepine pharmacology and central nervous system–mediated effects. Ochsner J 2013;13(2):214–223. PMID: 23789008

[40] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Temazepam. 2020. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/temazepam.html (accessed July 2020)

[41] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypnotics and anxiolytics treatment summary. 2020. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/hypnotics-and-anxiolytics.html (accessed July 2020)

[42] Warner J, Metcalfe C & King M. Evaluating the use of benzodiazepines following recent bereavement. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178(1):36–41. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.1.36

[43] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Zopiclone. 2020. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/zopiclone.html (accessed July 2020)

[44] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Zolpidem. 2020. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/zolpidem-tartrate.html (accessed July 2020)

[45] New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority. Zopiclone — indicated for short-term use only Prescriber Update. 2019. Available at: https://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/PUArticles/June2019/Zopiclone-Indicated-for-short-term-use-only.htm (accessed July 2020)

[46] Schifano F, Chiappini S, Corkery JM & Guirguis A. An insight into Z-drug abuse and dependence: an examination of reports to the European Medicines Agency database of suspected adverse drug reactions. Int J Neuropsychoph 2019;22(4):270–277. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyz007

[47] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guidance on the use of zaleplon, zolpidem and zopiclone for the short-term management of insomnia (TA77). 2004. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta77/resources/guidance-on-the-use-of-zaleplon-zolpidem-and-zopiclone-for-the-shortterm-management-of-insomnia-pdf-2294763557317 (accessed July 2020)

[48] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypnotics. 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/ktt6/resources/hypnotics-pdf-1632173521093 (accessed July 2020)

[49] Hajak G, Müller WE, Wittchen HU et al. Abuse and dependence potential for the non-benzodiazepine hypnotics zolpidem and zopiclone: a review of case reports and epidemiological data. Addiction 2003;98(10):1371–1378. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00491.x

[50] Brandt J & Leong C. Benzodiazepines and Z-Drugs: An updated review of major adverse outcomes reported on in epidemiologic research. Drugs R D 2017;17(4):493–507. doi: 10.1007/s40268-017-0207-7

[51] Coggins MD. Antihistamine Risks. 2013. Available at: https://www.todaysgeriatricmedicine.com/archive/0313p6.shtml (accessed July 2020)

[52] Anwari J & Iqbal S. Antihistamines and potentiation of opioid induced sedation and respiratory depression. Anaesthesia 2003;58(5):494–495. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03154_18.x

[53] Anderson K. How to treat insomnia and other sleep problems. Newcastle upon Tyne: Regional Sleep Service; 2018. 2018. Available at: http://www.neurone.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Teaching-slides-for-2018-sleep-training-day.pdf (accessed July 2020)

[54] Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med 2008;4(5):487-504. PMID: 18853708

You might also be interested in…

Sleep disorders: treatment

Sleep disorders: diagnosis