Shutterstock.com

After reading this learning article, you should be able to:

- Define insomnia, its prevalence and its impact on individuals;

- Recognise key risk factors and the consequences of untreated chronic insomnia;

- Explain the role of biopsychosocial factors in insomnia and the importance of holistic, non-pharmacological management, including sleep hygiene and CBT;

- Summarise the available pharmacological treatments, including their indications, safety considerations and appropriate use;

- Apply principles of responsible prescribing, including treatment duration, deprescribing, management of side effects and safe discontinuation;

- Describe the pharmacist’s role in supporting, advising and managing patients with insomnia.

Introduction

Insomnia affects a significant proportion of the global population, averaging between 5% and 50%, depending on the definition used1. It significantly impairs daily functioning, contributing to both mental and physical health issues2. Pharmacists are vital members of the multidisciplinary team and are well placed to support patients utilising evidence-based interventions3,4.

Insomnia is defined by persistent difficulties with sleep initiation, duration or quality, alongside daytime impairment, such as fatigue, mood disturbances or cognitive issues5. According to the International Classification of Diseases, 11th revision, daytime impairment is essential for a diagnosis of insomnia to be made6.

- Acute or short-term insomnia: characterised by difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep for fewer than three months and results in general sleep dissatisfaction and some form of daytime impairment. It is often linked to identifiable stressors and may resolve without treatment; although in some people, acute insomnia persists into a chronic state6.

- Chronic insomnia: frequent and persistent difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, resulting in general sleep dissatisfaction and some form of daytime impairment. Sleep disturbance and associated daytime symptoms occur at least several times per week for at least three months and requires targeted management6.

Chronic sleep deprivation increases the risk of various health conditions. Adults should aim for at least seven hours of quality sleep7, while oversleeping (>9 hours) may be appropriate in specific situations7. Sleep quality, consistency and timing are as important as duration2.

Aetiology of insomnia

While acute insomnia can occur independently of other conditions, chronic insomnia is often linked with comorbidities, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer, heart failure, depression, anxiety, pain and substance misuse8. Other factors can also influence sleep patterns, including age and gender.

The 3 P psychological model (Predisposing, Precipitating, and Perpetuating factors) can help to explain both the onset and persistence of insomnia9.

Depression and anxiety are the most frequent comorbidities associated with insomnia10. Even after these mental health conditions are managed, insomnia often remains11. Research shows that treating insomnia in individuals without depression can reduce the risk of developing it later12.

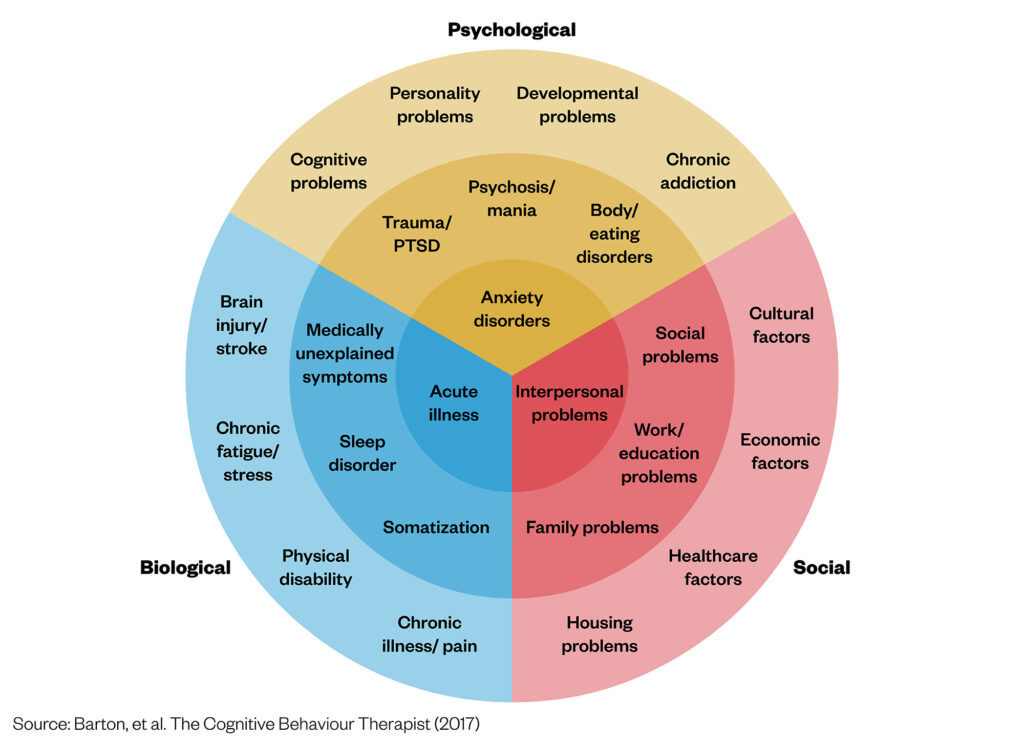

For example, a biopsychosocial approach is essential for understanding the heterogeneous factors associated with depression, such as sleep disorders, so that a holistic, tailored treatment plan can be devised.

Figure 1: Biopsychosocial model of insomnia

Chronic medical conditions — including cancer, COPD and especially chronic pain — are linked with a higher prevalence of insomnia13. In patients who have chronic pain, sleep disturbances and pain often reinforce each other, worsening both conditions14. This highlights how important it is to approach an assessment comprehensively to understand the root causes of insomnia.

Pathophysiology of insomnia

Insomnia is primarily driven by hyperarousal, involving physiological, cognitive and emotional factors that disrupt the circadian rhythm and impair sleep initiation and maintenance15. Wakefulness is promoted by neurotransmitters, such as histamine, noradrenaline, dopamine and orexins, while sleep is facilitated by gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), adenosine and melatonin16.

GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter and reduces arousal and promotes sleep through the GABAA receptor, a complex network of specific receptor subtypes. These subtypes are relevant for sleep because of their different locations in the brain and because some hypnotic drugs are selective for a particular subtype17, resulting in differentiated drug profiles.

The alpha-1 subtype probably mediates the sedative and hypnotic effects of many drugs that act at the benzodiazepine site; zolpidem targets this subtype preferentially. The alpha-3 subtype plays an important role in regulating sleep18. This subtype is particularly targeted by eszopiclone18. Traditional benzodiazepine drugs for insomnia act on the alpha-1, alpha-2, alpha-3 and alpha-5 subtypes18–20.

Contrary to the sleep promoting neurotransmitters, cortisol — which is known as the ‘stress hormone’ — links hyperarousal to insomnia21. Cortisol usually peaks in the morning and drops at night to aid sleep; however, it is elevated at night in insomnia, therefore, sustaining hyperarousal and perpetuating a cycle of poor sleep and stress22,23.

Risk factors

The risk factors associated with developing insomnia are outlined in the table below1,5.

What are the risks of untreated insomnia?

- Obesity: Fewer than seven hours of sleep increases risk of obesity — greater sleep loss is linked with higher obesity rates24;

- Diabetes: Short sleep duration is associated with higher glucose levels and increased risk of type 2 diabetes25;

- Cardiovascular disease: Higher risk of coronary heart disease, hypertension and stroke;

- Alzheimer’s disease: Potential increased risk26;

- Mental health: Worsening or triggering anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation and mania in bipolar disorder27;

- Falls: Increased risk, especially in older adults28;

- Work performance: Reduced productivity and higher workplace accident risk29;

- Substance misuse: Greater likelihood of using drugs or alcohol to self-medicate18;

- Driving: Impaired driving ability, increasing accident risk30.

Therefore, it is evident that untreated insomnia can result in substantial costs to the overall economy from reduced work productivity and increased risk of chronic health conditions31. It is essential for pharmacists are able to assess and screen patients for insomnia and support them effectively4.

Pharmacist’s role in insomnia management

- Assess and screen: Identify causes of insomnia, medication side effects, lifestyle factors and screen for risks, such as substance use or mental health issues;

- Educate: Advise on sleep hygiene, non-drug strategies and safe medication use. Explain side effects and signpost to helpful resources;

- Recommend treatments: Suggest appropriate evidence-based options based on symptoms and comorbidities;

- Support safe use: Monitor for drug interactions, misuse or side effects. Counsel on reducing risks (e.g. avoiding alcohol or driving when sedated);

- Collaborate: Liaise with prescribers and coordinate care across healthcare teams;

- Promote follow-up: Encourage ongoing reviews to evaluate effectiveness, support deprescribing and maintain rapport with patients.

Assessment of insomnia: sleep history

It is important to take a detailed sleep history when a patient presents with insomnia to understand the severity of the symptoms and to identify any risk factors that may make them more prone to experiencing insomnia1. The history should include the areas in Figure 22,32.

Investigations to consider

- Sleep diary: Encourage patients to track their sleep patterns using a sleep diary, such as the downloadable version from The Sleep Charity. This can help identify trends and potential triggers33;

- Insomnia Severity Index (ISI): A seven-question questionnaire that assesses the presence and severity of clinical insomnia, including sleep patterns, impact on daily function and concerns about sleep difficulties34;

- Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS): A tool to evaluate levels of daytime sleepiness35;

- Mental health screening: GAD-7 and PHQ-9 questionnaires are useful for assessing anxiety and depression, which may either contribute to or result from insomnia36;

- Relevant blood tests: Consider testing TSH (thyroid function)37 taking a full blood count (FBC) and iron studies to rule out any underlying medical causes38. Iron studies are particularly important, as low iron levels or iron deficiency anaemia can contribute to restless legs syndrome (RLS), a common but often overlooked cause of sleep disturbances, including difficulty falling and staying asleep39.

Key principles for managing insomnia

- Treat underlying causes before prescribing, including medical or lifestyle factors;

- Prioritise non-drug approaches, such as cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia and holistic support (e.g. social prescribers);

- Use medication for the shortest duration for effective treatment at the lowest effective dose;

- Tailor treatment to individual needs and comorbidities;

- Minimise risks of tolerance, dependence and withdrawal;

- Regularly review and plan for deprescribing where appropriate;

- Educate patients on safe use, sleep hygiene and lifestyle changes.

Non-pharmacological strategies

Treating insomnia is essential owing to its impact on quality of life and daily functioning and its association with mental and physical health risks, including depression, anxiety, diabetes and cardiovascular disease40. Before prescribing treatment for acute insomnia, it is crucial to address any comorbidities or medications that may contribute to symptoms, such as depression, anxiety or anaemia1. Adjusting medication timing, improving sleep hygiene, establishing a better bedtime routine and increasing exercise should be discussed with the patient41–43. Addressing social factors, such as financial or housing issues, through referrals to social prescribers or wellbeing coaches may provide holistic, personalised support44,45.

Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi) is the recommended first-line treatment, targeting the thoughts and behaviours that sustain insomnia1,17. However, limited availability through the NHS often necessitates alternatives, including private CBTi providers or apps, such as Sleepio, which is endorsed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 46.

Evidence-based pharmacological treatment should only be considered in the case of failure of CBTi, inability to engage with CBTi or unavailability of CBTi1.

Pharmacological treatment options: recently introduced options

Eszopiclone

Eszopiclone is a non-benzodiazepine GABAA receptor agonist that selectively enhances the activity of GABA, the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, specifically targeting the alpha-3 subtype receptor. Eszopiclone has been extensively researched in placebo-controlled studies of between four weeks and six months, consistently demonstrating improvement in sleep, next-day function and quality of life compared with placebo. Eszopiclone is licensed for the treatment of insomnia in adults, usually for a short duration, but it can be used for up to six months in certain situations, such as chronic insomnia, with regular patient reviews. The recommended dose starts at 1mg and can be increased to a maximum of 3mg (or 2mg for patients aged ≥65 years)47.

Discontinuation after short-term use and long-term use of eszopiclone is associated with a low frequency of potential withdrawal effects and low occurrence of rebound insomnia. In studies, there was no difference in risk of dependence between long-term use and short-term use47.

Eszopiclone has also been studied in insomnia comorbid with anxiety, depression, menopause and pain. Eszopiclone is the only hypnotic that has shown improvements for both sleep and measures of depression or anxiety compared with placebo when co-administered with an SSRI48–50.

Daridorexant

Daridorexant is a dual orexin receptor antagonist that promotes sleep by selectively inhibiting orexin neuropeptides, which regulate wakefulness, thereby facilitating both sleep onset and maintenance with minimal next-day residual effects51. The NICE recommendation for daridorexant specifies that it is for adults with insomnia (≥three nights/week for ≥three months) and whose daytime functioning is considerably affected, only after CBTi has been tried but not worked or when CBTi is not available or unsuitable51. The length of treatment should be as short as possible, with reassessment within three months of starting, and it should be stopped in people whose long-term insomnia has not responded adequately. If treatment is continued, there must be assessment of whether it is still working at regular intervals.

Clinical trials show that daridorexant improves the symptoms of insomnia compared with placebo for 12 months; although its effects if taken longer are unknown. It is important to note that study populations excluded patients with mental health comorbidities51,52. The recommended dose is 50mg once nightly, with 25mg as a possible starting dose based on clinical judgement53.

Pharmacological treatment options: older options

There are older medicines that can also be used to treat insomnia, as shown in Table 354.

Principles for deprescribing treatments for insomnia

It may be appropriate to consider deprescribing medications for several reasons, including polypharmacy, inappropriate prescribing, patient choice, risks outweighing the benefits, or if the condition has improved overall55. For example, benzodiazepines are recognised for the adverse effects they may have when being prescribed on a long-term basis55 as they can impair cognition, including having an impact on memory, attention, speed of processing and a delayed reaction time56.

Patients can be reluctant to stop taking their medicines, especially when they are effective — despite the harms outweighing the benefits. Therefore, it is important to explain to the patient the benefits and risks with long-term prescribing55.

Deprescribing: Do’s and Don’ts

Do:

- Regularly review treatment and explain risks, benefits and intended duration;

- Discuss tolerance, side effects and withdrawal symptoms;

- Reassure patients that tapering will be at a pace they are comfortable with;

- Involve a multidisciplinary team and refer to social prescribers or wellbeing coaches if needed;

- Refer to specialists (e.g. sleep clinic, mental health, substance misuse) if insomnia persists.

Don’t:

- Assume patients understand the long-term risks of hypnotics;

- Taper medications too quickly, risking a distressing withdrawal;

- Avoid discussions about deprescribing — it’s a vital part of safe care.

Conclusion

Insomnia is a prevalent and complex condition with significant personal, societal and economic impacts. The condition requires a comprehensive understanding of its underlying causes, associated risk factors and potential consequences to be able to effectively manage it. Pharmacists are ideally placed to support patients through early identification, education and holistic care that prioritises non-pharmacological approaches, such as sleep hygiene, CBTi and utilising personalised care roles. Where medication is necessary, pharmacists play a vital role in ensuring responsible prescribing, monitoring and deprescribing. By integrating clinical knowledge with patient-centred care, pharmacists can help to reduce the burden of insomnia and improve overall long-term health outcomes for patients.

Click here for the Lunivia® (eszopiclone) prescribing information

LUN062501 July 2025

- 1.Insomnia. NICE CKS. May 2025. Accessed July 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/insomnia/

- 2.Riemann D, Espie CA, Altena E, et al. The European Insomnia Guideline: An update on the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia 2023. Journal of Sleep Research. 2023;32(6). doi:10.1111/jsr.14035

- 3.Basheti MM, Gordon C, Grunstein R, Saini B. Exploring the pharmacist role in insomnia management and care provision: A scoping review. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 2025;65(1):102312. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2024.102312

- 4.Ashkanani FZ, Lindsey L, Rathbone AP. A systematic review and thematic synthesis exploring the role of pharmacists in supporting better sleep health and managing sleep disorders. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2023;31(2):153-164. doi:10.1093/ijpp/riac102

- 5.Insomnia Straight to the point of care . BMJ Best Practice. January 2025. Accessed July 2025. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/227/pdf/227/Insomnia.pdf

- 6.International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics Eleventh Revision Reference Guide. WHO. 2022. Accessed July 2025. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en

- 7.Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, et al. Recommended Amount of Sleep for a Healthy Adult: A Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. SLEEP. Published online June 1, 2015. doi:10.5665/sleep.4716

- 8.Morin CM, Benca R. Chronic insomnia. The Lancet. 2012;379(9821):1129-1141. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60750-2

- 9.Spielman AJ, Caruso LS, Glovinsky PB. A Behavioral Perspective on Insomnia Treatment. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1987;10(4):541-553. doi:10.1016/s0193-953x(18)30532-x

- 10.Freeman D, Sheaves B, Waite F, Harvey AG, Harrison PJ. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(7):628-637. doi:10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30136-x

- 11.Krystal AD, Prather AA, Ashbrook LH. The assessment and management of insomnia: an update. World Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):337-352. doi:10.1002/wps.20674

- 12.Li L, Wu C, Gan Y, Qu X, Lu Z. Insomnia and the risk of depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1). doi:10.1186/s12888-016-1075-3

- 13.Bjornsdottir E, Lindberg E, Benediktsdottir B, et al. Are symptoms of insomnia related to respiratory symptoms? Cross-sectional results from 10 European countries and Australia. BMJ Open. 2020;10(4):e032511. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032511

- 14.Mathias JL, Cant ML, Burke ALJ. Sleep disturbances and sleep disorders in adults living with chronic pain: a meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine. 2018;52:198-210. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2018.05.023

- 15.Dressle RJ, Riemann D. Hyperarousal in insomnia disorder: Current evidence and potential mechanisms. Journal of Sleep Research. 2023;32(6). doi:10.1111/jsr.13928

- 16.Wang Z, Liu J. The Molecular Basis of Insomnia: Implication for Therapeutic Approaches. Drug Development Research. 2016;77(8):427-436. doi:10.1002/ddr.21338

- 17.Wilson S, Anderson K, Baldwin D, et al. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus statement on evidence-based treatment of insomnia, parasomnias and circadian rhythm disorders: An update. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(8):923-947. doi:10.1177/0269881119855343

- 18.Lingford-Hughes A, Welch S, Peters L, Nutt D. BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity: recommendations from BAP. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(7):899-952. doi:10.1177/0269881112444324

- 19.Sanna E, Busonero F, Talani G, et al. Comparison of the effects of zaleplon, zolpidem, and triazolam at various GABAA receptor subtypes. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2002;451(2):103-110. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02191-x

- 20.Jia F, Goldstein PA, Harrison NL. The Modulation of Synaptic GABAA Receptors in the Thalamus by Eszopiclone and Zolpidem. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2009;328(3):1000-1006. doi:10.1124/jpet.108.146084

- 21.Dressle RJ, Feige B, Spiegelhalder K, et al. HPA axis activity in patients with chronic insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of case–control studies. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2022;62:101588. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101588

- 22.Passos GS, Youngstedt SD, Rozales AARC, et al. Insomnia Severity is Associated with Morning Cortisol and Psychological Health. Sleep Sci. 2023;16(01):092-096. doi:10.1055/s-0043-1767754

- 23.Vgontzas AN, Bixler EO, Lin HM, et al. Chronic Insomnia Is Associated with Nyctohemeral Activation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis: Clinical Implications. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2001;86(8):3787-3794. doi:10.1210/jcem.86.8.7778

- 24.Hasler G, Buysse DJ, Klaghofer R, et al. The Association Between Short Sleep Duration and Obesity in Young Adults: a 13-Year Prospective Study. Sleep. 2004;27(4):661-666. doi:10.1093/sleep/27.4.661

- 25.Insomnia could play direct role in causing type 2 diabetes. Diabetes UK. August 2022. Accessed July 2025. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/about-us/news-and-views/insomnia-could-play-direct-role-causing-type-2-diabetes

- 26.Almondes KM de, Costa MV, Malloy-Diniz LF, Diniz BS. Insomnia and risk of dementia in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2016;77:109-115. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.021

- 27.Hertenstein E, Feige B, Gmeiner T, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2019;43:96-105. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2018.10.006

- 28.Stone KL, Ensrud KE, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep, insomnia and falls in elderly patients. Sleep Medicine. 2008;9:S18-S22. doi:10.1016/s1389-9457(08)70012-1

- 29.Daley M, Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Grégoire JP, Savard J, Baillargeon L. Insomnia and its relationship to health-care utilization, work absenteeism, productivity and accidents. Sleep Medicine. 2009;10(4):427-438. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2008.04.005

- 30.Perrier J, Bertran F, Marie S, et al. Impaired Driving Performance Associated with Effect of Time Duration in Patients with Primary Insomnia. Sleep. 2014;37(9):1565-1573. doi:10.5665/sleep.4012

- 31.Hafner M, Stepanek M, Taylor J, et al. Why Sleep Matters-The Economic Costs of Insufficient Sleep: A Cross-Country Comparative Analysis. Rand Health Q. 2017;6(4):11. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5627640/

- 32.Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: final report. Sleep Health. 2015;1(4):233-243. doi:10.1016/j.sleh.2015.10.004

- 33.The Sleep-Charity Sleep Diary . The Sleep Charity. 2020. Accessed July 2025. https://thesleepcharity.org.uk/information-support/adults/sleep-diary/

- 34.Bastien C. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Medicine. 2001;2(4):297-307. doi:10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4

- 35.Lapin BR, Bena JF, Walia HK, Moul DE. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale: Validation of One-Dimensional Factor Structure in a Large Clinical Sample. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2018;14(08):1293-1301. doi:10.5664/jcsm.7258

- 36.Yamamoto M, Lim CT, Huang H, Spottswood M, Huang H. Insomnia in primary care: Considerations for screening, assessment, and management. The Journal of Medicine Access. 2023;7. doi:10.1177/27550834231156727

- 37.Song L, Lei J, Jiang K, et al. <p>The Association Between Subclinical Hypothyroidism and Sleep Quality: A Population-Based Study</p> RMHP. 2019;Volume 12:369-374. doi:10.2147/rmhp.s234552

- 38.Neumann SN, Li JJ, Yuan XD, et al. Anemia and insomnia: a cross-sectional study and meta-analysis. Chinese Medical Journal. 2020;134(6):675-681. doi:10.1097/cm9.0000000000001306

- 39.Management of restless legs syndrome. NICE CKS. June 2025. Accessed July 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/restless-legs-syndrome/management/management/

- 40.Van Houdenhove L, Buyse B, Gabriëls L, Van den Bergh O. Treating Primary Insomnia: Clinical Effectiveness and Predictors of Outcomes on Sleep, Daytime Function and Health-Related Quality of Life. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2011;18(3):312-321. doi:10.1007/s10880-011-9250-7

- 41.Stutz J, Eiholzer R, Spengler CM. Effects of Evening Exercise on Sleep in Healthy Participants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2018;49(2):269-287. doi:10.1007/s40279-018-1015-0

- 42.How to fall asleep faster and sleep better. NHS: Better Health. Accessed July 2025. https://www.nhs.uk/every-mind-matters/mental-wellbeing-tips/how-to-fall-asleep-faster-and-sleep-better/

- 43.Alnawwar MA, Alraddadi MI, Algethmi RA, Salem GA, Salem MA, Alharbi AA. The Effect of Physical Activity on Sleep Quality and Sleep Disorder: A Systematic Review. Cureus. Published online August 16, 2023. doi:10.7759/cureus.43595

- 44.Personalised care and support planning . NHS England. 2021. Accessed July 2025. https://www.england.nhs.uk/personalisedcare/pcsp/

- 45.Supported self-management health coaching guide. NHS England. Accessed July 2025. https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/health-coaching/

- 46.Sleepio to treat insomnia and insomnia symptoms: Medical technologies guidance . NICE. May 2022. Accessed July 2025. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg70

- 47.Decentralised Procedure Public Assessment Report Eszopiclone DE/H/5813/001-003/DC. Heads of Medicines Agencies. Accessed July 2025. https://mri.cts-mrp.eu/portal/fulltext-search?term=lunivia

- 48.Pollack M, Kinrys G, Krystal A, et al. Eszopiclone Coadministered With Escitalopram in Patients With Insomnia and Comorbid Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(5):551. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.551

- 49.Fava M, McCall WV, Krystal A, et al. Eszopiclone Co-Administered With Fluoxetine in Patients With Insomnia Coexisting With Major Depressive Disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59(11):1052-1060. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.016

- 50.Soares CN, Joffe H, Rubens R, Caron J, Roth T, Cohen L. Eszopiclone in Patients With Insomnia During Perimenopause and Early Postmenopause. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006;108(6):1402-1410. doi:10.1097/01.aog.0000245449.97365.97

- 51.Daridorexant for treating long-term insomnia. NICE. October 2023. Accessed July 2025. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta922

- 52.Kunz D, Dauvilliers Y, Benes H, et al. Long-Term Safety and Tolerability of Daridorexant in Patients with Insomnia Disorder. CNS Drugs. 2022;37(1):93-106. doi:10.1007/s40263-022-00980-8

- 53.QUVIVIQ 25 mg film-coated tablets. EMC. May 2025. Accessed July 2025. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/15359/smpc

- 54.Bazire S. Insomnia. Lloyd-Reinhold Publications Limited; 2020:127-132.

- 55.Horowitz M, Taylor D. The Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2024:297-490.

- 56.Schweizer E, Rickels K. Benzodiazepine dependence and withdrawal: a review of the syndrome and its clinical management. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;98(s393):95-101. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb05973.x