Shutterstock.com

After reading this article you should be able to:

- Identify patients that may be more likely to develop kidney stones;

- Recognise the presenting symptoms of kidney stones and understand how to take an appropriate history to aid diagnosis;

- Manage patients with kidney stones, including referral and provision of advice relating to future prevention.

Introduction

Kidney stones, or renal calculi, are hard deposits made of minerals and salts that form inside the kidneys1. They originate in the kidneys but can be found at any point in the urinary tract1–3. The stone may block urinary flow and pain arises from the obstruction of the kidneys collecting system (causing renal colic) or the ureter (causing uretic colic) as it attempts to pass out of the body1–3.

Many people may not experience symptoms; in 2010, results from one population study (n= 5,047) demonstrated an asymptomatic prevalence of 8%4. Acute presentations have an annual incidence of one to two cases per 1,000 people in the UK; it is estimated that 12% of men and 6% of women will have one episode of associated colic at some stage during their life5. Although preventable, more than half of those diagnosed with kidney stones will develop another within five to ten years6.

Peak age incidence for men is 40–60 years — two-thirds of whom are likely to have recurrent stones — and the peak age incidence is late 20s for women5. Hormonal differences, such as the protective effect of oestrogen, as well as a gender difference seen in urinary pH, calcium excretion and metabolic disorder prevalence, are thought to contribute to the lower incidence in females7.

Around 80% of kidney stones can be passed spontaneously without intervention; however, depending on the size of stone and patient factors (e.g. the anatomy of the patient), medication or surgical interventions may be required5,8.

Global incidence of kidney stones is increasing9. This increasing prevalence and potential for prevention of stones in working age adults makes this an area in which pharmacists can have an impact in identifying, triaging and supporting patients10,11.

Causes and pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of stone formation is still debated; however, it is thought to be a heterogeneous process1. Stones are more likely to form when the urine is concentrated and there is an excess of waste products, such as minerals, which crystallise, nucleate and grow to form stones1.

Composition of the stone may allow for causes and risk factors to be identified; see Table1,2,8,12.

Risk factors

Some patients will be more at risk of kidney stones; non-modifiable risk factors include:

- Male sex: the incidence is 2.5:1 male to female, but this gap looks to be narrowing10,13;

- White ethnicity: in 1994, US study data showed the highest prevalence in white men followed by Hispanic, Asian and Black men14;

- Family history: those with a family history of kidney stones are more likely to develop multiple stones and experience early recurrence1;

- Medical history: several conditions increase the risk of stone formation, including anatomical abnormalities of the kidney or urinary tract, genetic conditions affecting metabolism (e.g. adenine phosphoribosyltransferase [APRT] deficiency, cystinuria, Dent disease), gastro-intestinal conditions affecting absorption (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease), conditions that alter urinary pH (e.g. chronic nephritis, gout), volume or concentration3,8,11,15–17.

There is some evidence that occupational exposure to heat increases risk, although evidence is weaker in this area5. Occupational exposure to cadmium and lead is associated with stone formation5. Prevalence of kidney stones also increases with increasing weight/BMI14.

Signs and symptoms

Although some patients will be asymptomatic, patients with larger stones are likely to experience renal or ureteric colic pain and present to a healthcare professional for assistance in a community pharmacy, GP or acute care setting.

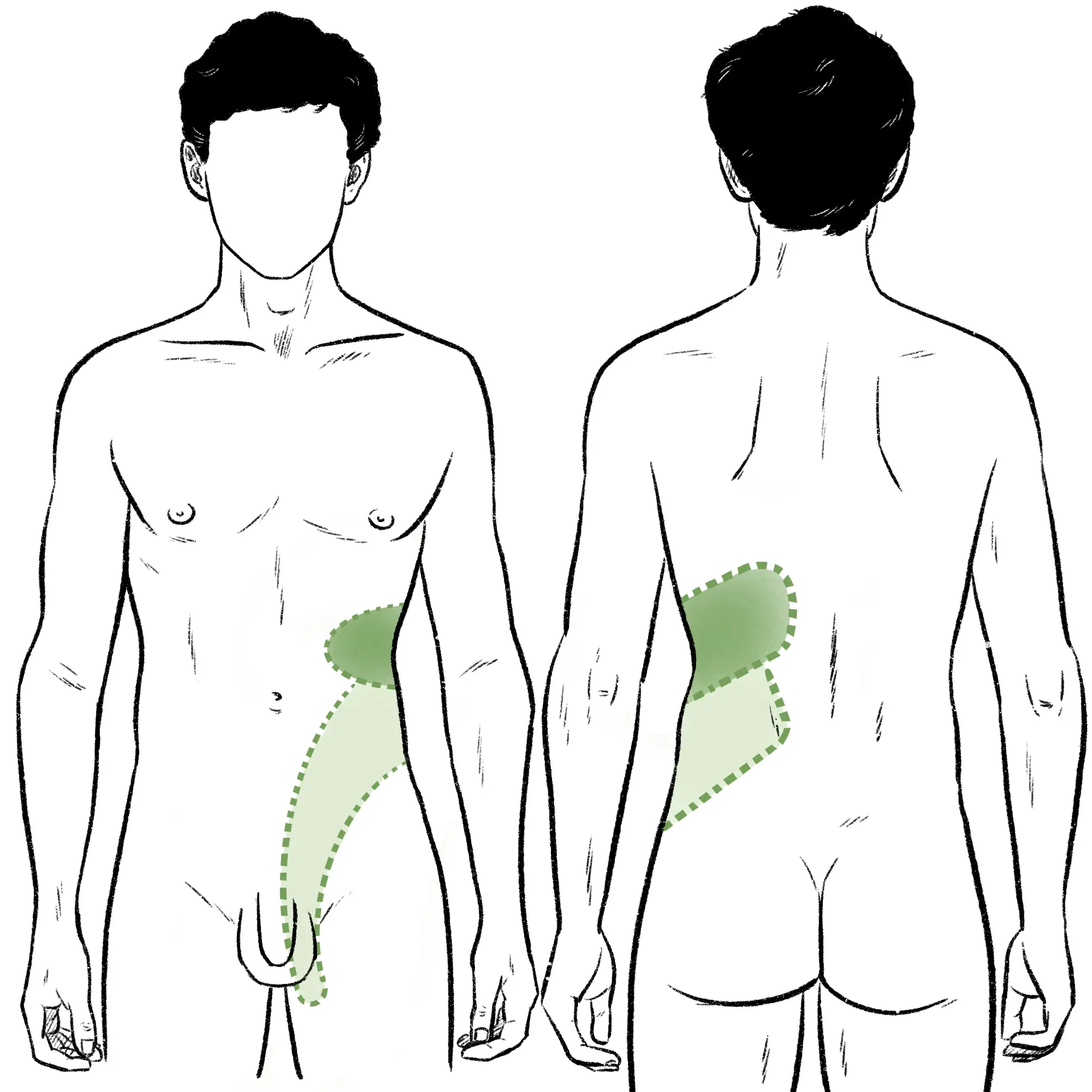

Pain is severe, intense and abrupt in onset; it is unilateral, originating in the loin or flank radiating down to the groin/testicles in men or labia in women, see Figure8. Pain is caused by increased intraluminal pressure stretching the nerve endings of the collecting system or ureter1. Other contributors to pain may include local inflammatory mediators, hyperperistalsis (i.e. excessive or excessively vigorous peristalsis of ureters), mucosal irritation and oedema1.

Wes Mountain/The Pharmaceutical Journal

Pain occurs in spasms (with intervals of dull ache or no pain) that can last anywhere between minutes to hours1,8. A patient may describe it as the worst pain that they have ever experienced. At its most severe, the pain may be accompanied by nausea and vomiting. A standard scoring system can be used to monitor pain and the STONE score (online calculator can be found here) can be used to determine the risk of stone presence and prevent re-imaging in those with a previous history18.

If the stone irritates the detrusor muscle or blocks the vesico-ureteric junction, patients may experience increased urinary frequency, pain on urination or straining8.

Patients will require immediate hospital admission if:

- There are signs of systemic infection (e.g. fever or sweats) or sepsis;

- They have pre-existing conditions that increases risk of acute kidney injury (e.g. chronic kidney disease, transplanted kidney);

- They are dehydrated and can no longer take oral fluids owing to nausea/vomiting8.

Diagnosis

All patients with suspected renal colic should be referred urgently (within 24 hours) for non-contrast CT imaging to confirm diagnosis3. Ultrasound can be used as an alternative for pregnant women8. Blood tests (full blood count, urea and electrolytes) to confirm kidney function and potential precipitating conditions should be completed in tandem1.

The CT scan will confirm the diagnosis, number, location and size of stones, as well as anatomical abnormalities associated with recurrent stones8. Where relevant, women of childbearing age should be offered a pregnancy test to rule out ectopic pregnancy, which may have overlapping symptoms, such as pelvic pain and urinary symptoms1.

The location and the type of pain can help to distinguish kidney stones from other conditions, such as appendicitis, where the pain is in the right lower quadrant and is typically more persistent and accompanied by fever1. Patients with renal colic may be more restless and unable to lie still unlike the pain in peritonitis, which is an infection in the thin layer of tissue in the abdomen8.

There may be haematuria (blood in the urine) present on a urinary dipstick, which should be undertaken to rule out the diagnosis of a urinary tract infection or pyelonephritis1,8.

Management

Supportive care

Patients with kidney stones will need assistance with pain relief. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends that a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) should be used as first-line treatment by any route3. However, renal function should be checked before prescribing an NSAID as some patients may develop acute kidney injury from the stone and NSAIDs are contraindicated in renal failure19. Intravenous paracetamol can be used if NSAIDs are contraindicated or do not offer sufficient relief, with opiates being a third-line option3. Anti-emetics can assist with nausea1. Antibiotics should be given if urinary cultures are positive1.

Stone removal

Symptoms, size and placement of stones determine the management route taken to remove the stone:

- Asymptomatic stones less than 5mm: watchful waiting employed as spontaneous stone passage is more likely with smaller stones11;

- Asymptomatic stones larger than 5mm: watchful waiting with patient agreement as to risks and benefits8. These stones should not affect quality of life if the patient has limited symptoms and may not need intervention, but there is the risk of location change and obstruction, bleeding and the development of symptoms3;

- Symptomatic stones less than 10mm: may benefit from medical expulsive therapy, which is where a medication is used to help patients pass the stone spontaneously. Alpha blockers are used for this indication (unlicensed [e.g. Tamsulosin]), with 400 micrograms daily until stone expulsion20. Inhibition of smooth muscle contraction in the ureter assists the passage of the stone into the bladder21.

Stones unlikely to pass, where the pain is ongoing (48 hours) or not tolerated, may be candidates for a procedure for removal3. The choice of procedure is based on anatomy, stone size and patient factors:

- Shockwave lithotripsy: uses shock waves to break up the stone into easier to pass fragments8;

- Percutaneous nephrolithotomy: endoscopy of kidney during which the stone is broken down by instruments or lasers and removed2;

- Ureteroscopy: endoscopy of the ureter with instruments or energy waves for break down the stone for removal8;

- Open surgery: rarely used, but remains an option for when the above procedures fail or are unlikely to be successful11.

Once passed, the stone can be sent for analysis to determine composition; this can help tailor future prevention advice to the patient10.

Advice on prevention

Given the high risk of reoccurrence, pharmacists can have a role in counselling patients on lifestyle modifications to reduce risk of new stone formation. The BMJ has produced an article on dietary management that may be useful when stone analysis has been performed to tailor the advice to the patient based on the stone composition10. Despite calcium being the most prevalent element found in kidney stones, restriction of dietary calcium actually adversely affects stone reoccurrence10. For patients unsure of their usual calcium intake, the online chart by the Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation can be used22.

If lifestyle advise fails, patients with recurrent stones that are predominantly (more than 50%) calcium oxalate may benefit from potassium citrate or thiazide treatment2. Patients taking medications that can induce kidney stone formation should have their use reviewed, considering the patient holistically and whether any metabolic or dietary factors have since resolved. Lifestyle adjustments may prevent reoccurrence, and drug removal may not be required23.

General prevention advice for patients is shown in the Box below8,10,11.

Box: Summary of guidance on preventing kidney stones

Fluid intake advice:

- 2.5–3.0L of water a day for adults, and 1–2L a day for children, depending on age;

- Water is the preferred fluid for drinking;

- Avoid carbonated drinks and calorie-containing fluids;

- Reduce alcohol intake;

- Add lemon juice to water (citrate may inhibit stone formation)

- Address any fluid losses (e.g. sweating in hot climates or vomiting) with additional fluid intake.

Nutritional advice:

- Limit salt intake to no more than 6 grams, and for children and young people (depending on their age), 2–6 grams a day. Excess sodium intake leads to an increased urinary calcium concentration and reduced urinary citrate, promoting calcium crystallisation;

- Do not restrict dietary calcium and aim for a calcium intake of 700–1,200mg a day, and for children and young people (depending on their age), 350–1,000 mg a day;

- Reduce protein from animal sources; diets rich in meat protein affects urinary citrate, oxalate and calcium levels to increase risk of stone formation;

- Eat fruits and vegetables that are high in fibre.

Complications

Suspected kidney stones should not be ignored. Complications include obstruction of urinary flow and infection; persisting obstruction reduces renal blood flow and may cause kidney damage and chronic kidney disease1,8,11,24,25. Presence of kidney stones is also associated with coronary heart disease, stroke and renal cancer26,27.

Patient case study

A 48-year-old male (95kg) presents to the community pharmacy after experiencing back pain for two days that comes on at night and lasts for approximately four hours. Paracetamol has been tried but did not provide any relief.

The pharmacist asks the patient the following questions:

- Where is the location of the pain?

- Is there any pain or change in urination?

- Has there been any injury to the back or any strenuous activity?

- Is the pain only at night?

- Are there any other symptoms?

The patient reported pain in the upper back on the right-hand side only. They had not noticed any changes in urination but admitted their urine was generally on the darker side. They had not experienced any injuries or completed any activities that could have resulted in muscle damage. They felt some slight throbbing during the day, but the pain at night was the worst thing they have ever experienced and they were vomiting as they were in so much pain. Vomiting did not relieve the pain.

Based on the further description of the patient, the pharmacist recommended that they seek an urgent medical appointment as they may need a referral for a potential kidney stone.

The patient saw their GP that day, was referred to accident and emergency with a letter for an urgent CT. The CT scan showed a small luminous mass of 4mm in the right kidney consistent with kidney stones. The patients GFR was 45mL/minute. The patient was admitted overnight and received paracetamol and codeine for pain. Owing to stone size, they were discharged and told to drink two to three litres of water per day to promote removal, with a follow-up planned for further imaging in five days’ time.

The patient passed their stone three days after discharge from hospital. Further imaging confirmed absence of the stone. Advice was given on weight reduction and fluid management to prevent reoccurrence.

Best practice

- All suspected symptomatic patients with kidney stones should be referred for examination;

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the first-line analgesic for renal colic if kidney function is unaffected;

- All patients with kidney stones should be provided with lifestyle counselling to reduce risk of reoccurrence.

- This article was amended on 21 November 2024 to clarify that women of child-bearing age should be offered a pregnancy test where relevant

- 1.BMJ Best Practice. BMJ Best Practice. 2021. Accessed November 2024. http://www.bestpractice.bmj.com

- 2.Kidney stones. NHS. 2022. Accessed November 2024. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/kidney-stones/

- 3.Renal and ureteric stones: assessment and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019. Accessed November 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng118

- 4.Boyce CJ, Pickhardt PJ, Lawrence EM, Kim DH, Bruce RJ. Prevalence of Urolithiasis in Asymptomatic Adults: Objective Determination Using Low Dose Noncontrast Computerized Tomography. Journal of Urology. 2010;183(3):1017-1021. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.047

- 5.Occupational risks for urolithiasis: IIAC information note. Public Health England and Industrial Injuries Advisory Council. 2018. Accessed November 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/occupational-risks-for-urolithiasis-iiac-information-note/occupational-risks-for-urolithiasis-iiac-information-note

- 6.Uribarri J. The First Kidney Stone. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111(12):1006. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-111-12-1006

- 7.Gillams K, Juliebø-Jones P, Juliebø SØ, Somani BK. Gender Differences in Kidney Stone Disease (KSD): Findings from a Systematic Review. Curr Urol Rep. 2021;22(10). doi:10.1007/s11934-021-01066-6

- 8.Clinical Knowledge Summary: Renal or ureteric colic – acute. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020. Accessed November 2024. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/renal-or-ureteric-colic-acute

- 9.Lang J, Narendrula A, El-Zawahry A, Sindhwani P, Ekwenna O. Global Trends in Incidence and Burden of Urolithiasis from 1990 to 2019: An Analysis of Global Burden of Disease Study Data. European Urology Open Science. 2022;35:37-46. doi:10.1016/j.euros.2021.10.008

- 10.Morgan MSC, Pearle MS. Medical management of renal stones. BMJ. Published online March 14, 2016:i52. doi:10.1136/bmj.i52

- 11.Urolithiasis [Clinical Guideline]. European Association of Urology. 2024. Accessed November 2024. https://uroweb.org/guidelines/urolithiasis/chapter/guidelines

- 12.Kidney stones. British Association of Urological Surgeons. 2024. Accessed November 2024. https://www.baus.org.uk/patients/conditions/6/kidney_stones/

- 13.Stamatelou KK, Francis ME, Jones CA, Nyberg LM Jr, Curhan GC. Time trends in reported prevalence of kidney stones in the United States: 1976–199411.See Editorial by Goldfarb, p. 1951. Kidney International. 2003;63(5):1817-1823. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00917.x

- 14.Soucie JM, Thun MJ, Coates RJ, McClellan W, Austin H. Demographic and geographic variability of kidney stones in the United States. Kidney International. 1994;46(3):893-899. doi:10.1038/ki.1994.347

- 15.Morse JM. The PI as Participant. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(12):1655-1655. doi:10.1177/1049732309353421

- 16.Aune D, Mahamat-Saleh Y, Norat T, Riboli E. Body fatness, diabetes, physical activity and risk of kidney stones: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33(11):1033-1047. doi:10.1007/s10654-018-0426-4

- 17.Edvardsson VO, Goldfarb DS, Lieske JC, et al. Hereditary causes of kidney stones and chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28(10):1923-1942. doi:10.1007/s00467-012-2329-z

- 18.STONE Score for Uncomplicated Ureteral Stone. MDCalc. 2024. Accessed November 2024. https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/10110/stone-score-uncomplicated-ureteral-stone

- 19.British National Formulary. British National Formulary. Accessed November 2024. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/

- 20.How and when to take tamsulosin. NHS . February 2023. Accessed November 2024. https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/tamsulosin/how-and-when-to-take-tamsulosin/#:~:text=The%20usual%20dose%20of%20tamsulosin,than%20a%20milligram%20(mg

- 21.Sun Y, Lei GL, Yang L, Wei Q, Wei X. Is tamsulosin effective for the passage of symptomatic ureteral stones. Medicine. 2019;98(10):e14796. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000014796

- 22.Steps to Estimate Your Calcium Intake. Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation. Accessed November 2024. https://www.bonehealthandosteoporosis.org/patients/treatment/calciumvitamin-d/steps-to-estimate-your-calcium-intake/

- 23.Matlaga B, Shah O, Assimos D. Drug-induced urinary calculi. Rev Urol. 2003;5(4):227-231. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16985842

- 24.Managing patients with renal colic in primary care: know when to hold them. Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand. 2014. Accessed November 2024. https://bpac.org.nz/bpj/2014/april/colic.aspx

- 25.Shang W, Li L, Ren Y, et al. History of kidney stones and risk of chronic kidney disease: a meta-analysis. PeerJ. 2017;5:e2907. doi:10.7717/peerj.2907

- 26.Gambaro A, Lombardi G, Caletti C, Ribichini FL, Ferraro PM, Gambaro G. Nephrolithiasis: A Red Flag for Cardiovascular Risk. JCM. 2022;11(19):5512. doi:10.3390/jcm11195512

- 27.Peng JP, Zheng H. Kidney stones may increase the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Medicine. 2017;96(34):e7898. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000007898

4 comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You might also be interested in…

‘I have developed good working relationships with my patients beyond their diagnosis’ – a day in the life of a renal pharmacist

UK Clinical Pharmacy Association launches pharmacogenomics guidance

A good article. Learnt a lot. How can I acquire a CPD certificate?

Many thanks for your comment. I am the senior editor for research and learning at the PJ. This piece is one of our shorter learning articles which do not generate CPD certificates. To see our full list of available CPD modules you can go to 'My account' and then 'My CPD'.

Under the 'Diagnosis' subheading where it says "Women of childbearing age should have a pregnancy test to rule out ectopic pregnancy". This suggests all women should be assumed to be pregnant and could be perceived as condescending and patronising. Perhaps it should instead say something along the lines of "Where relevant women of child bearing age should be offered a pregnancy test".

Many thanks for your comment. I am the senior editor for research and learning at the PJ. We have considered your comment and agree with the sentiment so will edit this sentence accordingly. Many thanks.