Nerthuz/Alamy Stock Photo

By the end of this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the fundamental pathophysiological principles of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM);

- Describe how obstructive HCM (oHCM) causes symptoms through left ventricular outflow tract obstruction;

- Understand the range of clinical presentations for HCM and how genetic factors affect risk of developing the condition;

- Know which conventional medications are used as first-line options for HCM and understand their limitations;

- Understand the mechanism of action of myosin inhibitors and how mavacamten is being used to treat oHCM;

- Identify important safety considerations for mavacamten;

- Know when patients require genetic testing, as well as how their results can influence dosing and risk of interactions.

Cardiomyopathies are primary heart muscle disorders in which the observed structural and functional abnormalities are not explained by coronary artery disease (CAD), hypertension, valvular disease or congenital heart disease (CHD)1.

There are different types of cardiomyopathies, which are broadly defined by their phenotype (i.e. appearance). These types of cardiomyopathies include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM), arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) and non-dilated left ventricular cardiomyopathy (NDLVC)2.

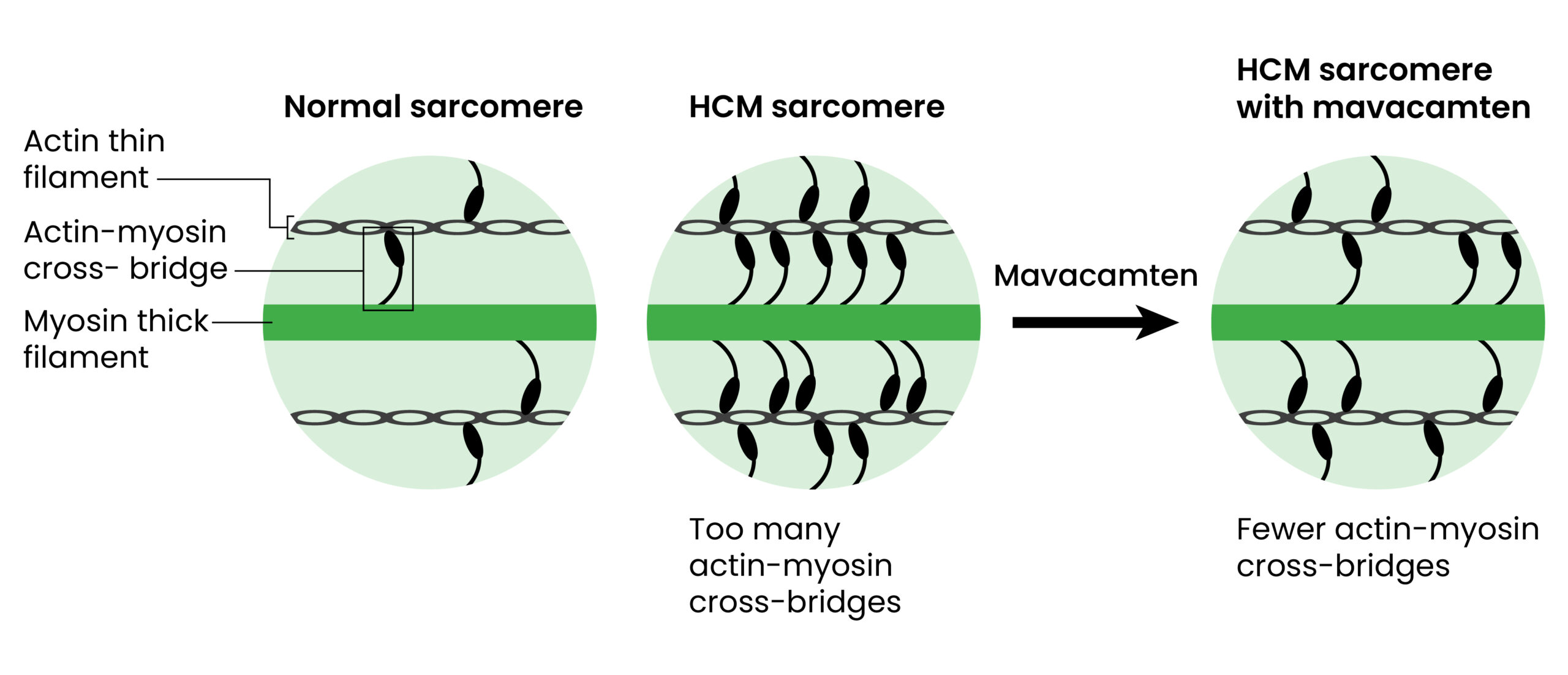

Treatment and prognosis of these different types of cardiomyopathies are very different. For the purpose of this article, the focus will be on HCM. HCM is defined as the presence of increased left ventricular wall thickness (i.e. left ventricular hypertrophy) that is not solely explained by abnormal loading conditions such as hypertension3. It is also primarily a genetic condition, which is often caused by mutations in genes encoding sarcomere proteins found in heart muscle. These genetic changes lead to dysfunction of the cardiac sarcomere, resulting in excessive cardiac myosin–actin cross-bridging and increased sensitivity to calcium4. HCM is a progressive condition, leading to increased symptoms and risk of complications over time. However, for some, it can remain asymptomatic and have no effect on day-to-day living. Of note, the left ventricular function in HCM can be either preserved or impaired.

Epidemiology and symptoms

HCM is a relatively common condition, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in every 500 people in the general UK population. The condition has no significant differences across ethnicities or geographical location5. It is a heterogenous condition for clinical presentation and outcome, with some patients being asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic, while others experience severe symptoms that impact functional capacity, quality of life and life expectancy6,7. The most frequent symptoms are exertional dyspnoea, palpitations, fatigue, pre-syncope, syncope and angina. Significant complications include atrial fibrillation, cardio-embolic stroke, heart failure and sudden death8,9. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator placement can reduce the risk of the latter in high-risk patients10,11.

Diagnosis and management

Diagnosis of HCM is clinical and based on the presence of unexplained left ventricular hypertrophy. Clinical work up includes taking a detailed personal and family history, ECG and cardiac imaging, which usually include echo and cardiac MRI4. Around 50% of patients with a clinical diagnosis of HCM are found to carry a mutation in a gene, which encodes a sarcomeric protein — most commonly MYBPC3 and MYH7. Results of genetic testing can aid diagnosis and help family genetic screening as these mutations are mostly inherited with an autosomal dominant pattern (50% risk of inheritance) and have incomplete penetrance. However, not all mutation carriers develop the condition12.

Relatives with no signs of cardiomyopathy can be tested to establish whether they carry the familial mutation and require ongoing surveillance as they may develop symptoms later in life. In patients with HCM who are not found to carry a mutation, the condition is likely owing to a polygenic predisposition and acquired factors such as hypertension13. In these patients, the risk of family members also developing the condition is much lower. Genetic testing is funded by the NHS across the UK. In England, funding is provided via the NHS genomic medicine service.

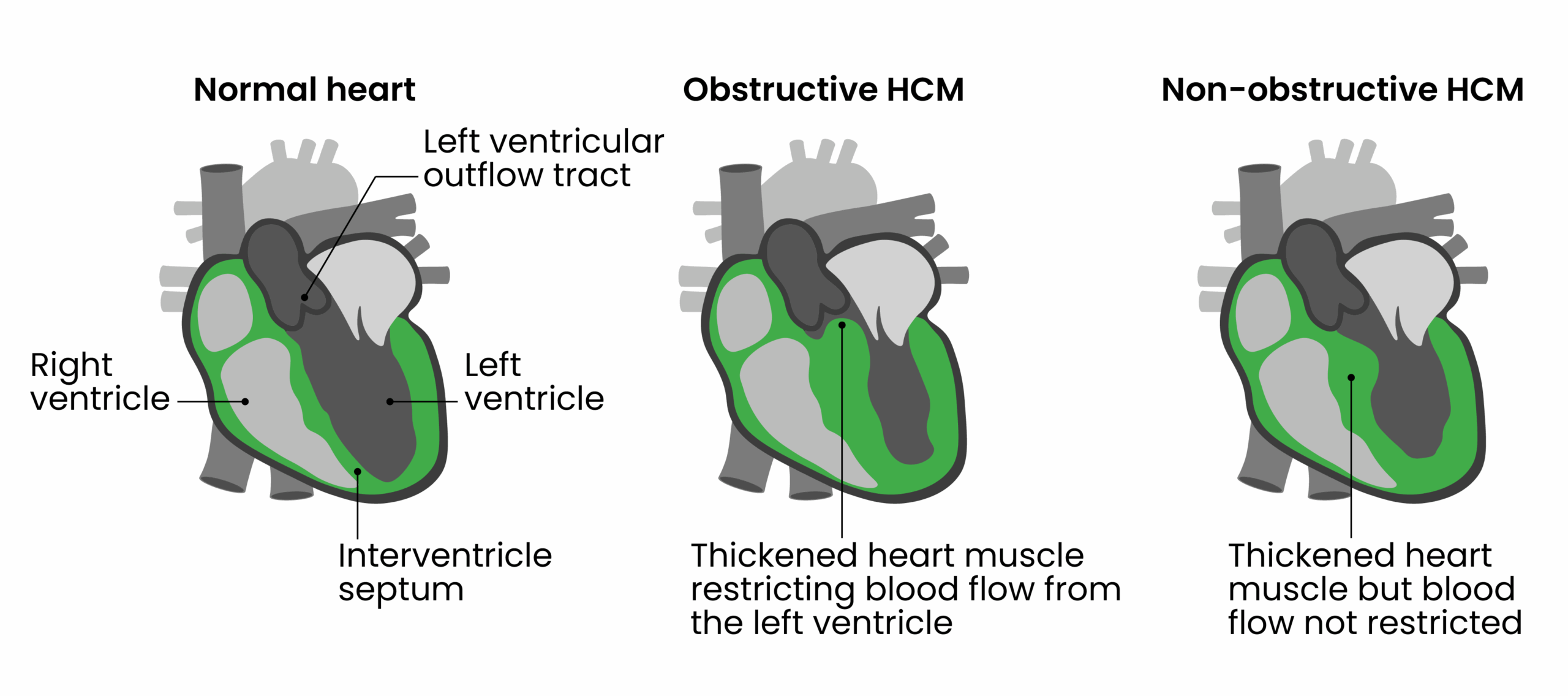

The most common cause for symptoms in HCM is left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO), which is present in around one-third of patients at rest. For a further one-third of patients, symptoms develop only with exercise or provocation manoeuvres (i.e. specific exercises or stress tests that potentiate the obstruction)14. An important feature of obstructive HCM (oHCM) is a change in dynamic pressure gradient across the left ventricular outflow tract owing to systolic anterior movement of the mitral valve leaflets that brings them into contact with the interventricular septum (Figure 1). This a complex phenomenon that is related to anatomical, geometrical and flow factors. In layperson terms, the thickened heart muscle makes it harder for the heart to pump blood out effectively.

LVOTO is associated with exertional symptoms (i.e. shortness of breath, chest pain and pre-syncope/syncope) and an increased risk of sudden death15. Management is medical in the first instance, while historically, patients with drug refractory symptoms have been considered for invasive septal reduction therapies (SRTs). These procedures have a risk of serious complications. In addition, robust, long-term data are lacking, given that they have not been studied in large randomised controlled trials16.

By convention, LVOTO is defined as a peak Doppler LV outflow tract gradient of ≥30 mmHg; however, the threshold for invasive treatment is usually considered to be ≥50 mmHg17. Most asymptomatic patients with LVOTO do not require treatment, but in a very small number of selected cases, pharmacological treatment to reduce LV pressures may be considered3.

First-line treatment of oHCM includes oral beta-blockers and/or non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers1. Both drug classes slow heart rate, and their modest negative inotropic actions may provide some reduction of LVOT gradient. Disopyramide, a Class 1a antiarrhythmic agent, may be added owing to its additional negative inotropic action; however, its anticholinergic side effects frequently limit its use in practice. While these three drug classes have been the mainstay of pharmacologic treatment for decades, their use is largely supported by observational studies1 with none addressing the underlying molecular mechanisms of the disease. Lifestyle advice is also important, which includes avoiding dehydration, excessive alcohol and vasodilators, such as nitrates and PDE5 inhibitors. Weight reduction where appropriate is also encouraged3.

SRTs

SRTs include surgical septal myectomy — an open-heart surgery where surgeons widen the LV outflow tract by resecting some of the muscle in the thickened septum — and alcohol septal ablation, which is a percutaneous procedure that thins the thickened septum by creating a scar secondary to intracoronary alcohol injection. Historically, these therapies have been considered in patients with severe drug-refractory symptoms. The choice between alcohol septal ablation and septal myectomy should be based on a multidisciplinary discussion and patient preference. While recovery time for the catheter-based approach is quicker, the procedure is less effective than surgery in relieving symptoms and has a higher risk, requiring permanent pacing (10%). Alcohol septal ablation is often considered in patients with a high surgical risk. Although both procedures can substantially improve symptoms and quality of life, they may not be an option owing to operative risk and patient preference. To be effective and safe, these procedures require substantial operator experience18, which is limited mainly to a few centres of excellence and is not accessible to many patients worldwide. Optimal medical management of oHCM, therefore, represents a major unmet need.

Cardiac myosin inhibitors

Mavacamten is a first-in-class cardiac myosin adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) inhibitor that acts by reducing actin–myosin cross-bridge formation, reducing contractility and improving myocardial energetics (Figure 2). The drug represents the first disease-specific treatment for oHCM, targeting the core pathophysiological mechanism of the disease19. It should also be noted that other agents that inhibit cardiac myosin ATPase are in development, and the results of a phase III study, published in 2024, have revealed favourable outcomes 20.

https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.120.006853)

Mavacamten reduces myosin–actin cross-bridge formation by decreasing the number of myosin heads that can enter the ‘on actin’ or power-generating state, shifting myosin population towards an energy-sparing, super-relaxed ‘off actin’ state by reversibly binding to myosin ATPase. The results of structural studies have shown that while HCM mutations disrupt normal interactions between sarcomere proteins, mavacamten normalises these interactions and restores physiologic sarcomere function. By normalising the ratio of ‘on’ and ‘off’ myosin heads, mavacamten reduces sarcomeric hyperactivity and resultant myocardial hypercontractility, lowering LVOT obstruction and LV filling pressure. The results of a study, published in 2022, show that mavacamten reduces maximal force, Ca2+ sensitivity, myocardial energy demands and diastolic dysfunction19.

The findings of an EXPLORER-HCM trial, published in 2020, showed that mavacamten when added to current standard medical therapy was associated with increased exercise capacity, reduced LVOT gradient and improved symptoms and quality of life21. Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), published in 2023, recommends mavacamten as an option for treating symptomatic oHCM in adults who have NYHA II/III as an add-on to existing therapy22. Given the specialist nature of the condition and medication, this is being undertaken in selected cardiac centres across the UK. Mavacamten is a high-cost, red-listed medicine funded by NHS England and available through specialist centres. It should also be noted that mavacamten is approved exclusively for oHCM.

Essential pharmacokinetic properties of mavacamten have been well defined. Its metabolism primarily takes place in the liver via cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes. Although this is predominantly via CYP2C19 (74%), other enzymes, such as CYP3A4 and CYP2C9, have been shown to contribute to its metabolism (18% and 8%, respectively)23. The large reliance on clearance from the CYP2C19 enzyme has led to the requirement for patients to undergo genotyping prior to starting treatment, where poor CYP2C19 metabolisers can be identified, started on a lower initial dose and can only receive a maximum of 5mg daily, which is one-third of the maximum licensed dose (15mg daily). This is owing to exposure being three-fold higher in poor metabolisers23.

In addition to genotyping to assess an individual’s CYP2C19 status, there is a significant number of drug–drug interactions based on CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 inhibition or induction. Individual response to mavacamten is, therefore, difficult to predict, leading to a complex initiation, titration and potential dose adjustment protocol for the drug. Frequent echocardiograms are required to monitor safety and treatment response, assessing both LVOT gradient and LV function. Mavacamten should be stopped if LVEF is < 50% at any clinical visit and only restarted after four weeks if the LVEF is ≥ 50%. Mavacamten is thought to have teratogenic effects as based on animal studies, so women of childbearing potential must have a negative pregnancy test before initiation and use effective contraception during, and for six months after, treatment.

Certain combinations should be avoided, such as strong CYP2C19 inhibitors used alongside strong CYP3A4 inhibitors. In other cases, depending on an individual’s CYP2C19 genotype, medicines that are intermediate inhibitors or inducers of CYP2C19 or CYP3A4 may necessitate dose adjustments of mavacamten23.

Common examples of CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 inhibitors and inducers related to mavacamten are listed in Table 124. If there is any uncertainty or a clinical need for co-prescribing, prescribers are encouraged to consult cardiomyopathy specialists for guidance.

It should be noted that Table 1 lists grapefruit juice — a CYP3A4 inhibitor — and herbal supplements such as St John’s Wort — a CYP inducer — so it is important to explicitly ask patients about use of herbal and other dietary supplements during history taking. Table 1 is not an exhaustive list so for up-to-date information, please refer to the product licence, which is available here.

Side effects of mavacamten

The most commonly reported adverse reactions with mavacamten are dizziness (17%), dyspnoea (12%), systolic dysfunction (5%) and syncope (5%). These reactions are summarised in the Table 223.

Role of pharmacists in clinical practice

There are several important functions that pharmacists will need to perform to support the safe treatment of patients on mavacamten:

- GP, community, and hospital pharmacists should screen for drug–drug interactions before supplying new medications to patients on mavacamten;

- Check the patient’s use of over-the-counter (OTC) and herbal medicines for potential interactions;

- Provide counselling to patients on avoiding certain foods and supplements. Specifically, they should avoid grapefruit and grapefruit juice, which can increase mavacamten plasma concentrations, as well as any supplements or herbal products that strongly inhibit CYP2C19, or CYP3A4, since these can alter drug metabolism and increase the risk of adverse effects. Patients should be encouraged to consult the specialist cardiac team before starting any new supplement or OTC product while on mavacamten;

- Contact cardiomyopathy centres for expert advice if there is uncertainty around potential interactions or required dose adjustments;

- Ensure regular follow-up and adherence to monitoring protocols to optimise patient safety and therapeutic outcomes.

Summary

HCM is a genetic disorder characterised by left ventricular hypertrophy that is not explained by conditions that increase workload on the heart, such as hypertension or valvular disease. The pharmacological treatment of HCM includes beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers and disopyramide, which primarily manage symptoms but do not target the disease mechanism.

Mavacamten is a first-in-class cardiac myosin ATPase inhibitor, which directly addresses the underlying pathophysiology of oHCM. NICE has approved mavacamten as an option in those with NYHA class II/III oHCM in adults as an add-on therapy, which is available in selected centres in the UK. Genetic CYP2C19 testing is also required before initiation to determine metabolism status.

Pharmacists should avoid the prescribing of concomitant strong CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 inhibitors. In addition, echocardiography monitoring is essential during dose titration.

Common potential side effects of mavacamten include fatigue, dizziness, shortness of breath and chest discomfort, with heart failure exacerbation a potentially serious adverse effect. Women of childbearing potential must also have a negative pregnancy test before initiation, while effective contraception is required during treatment and for six months after stopping.

By understanding these important points, pharmacists and healthcare professionals can play a crucial role in ensuring the safe and effective use of mavacamten in treating obstructive HCM.

- 1.Arbelo E, Protonotarios A, Gimeno JR, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies. European Heart Journal. 2023;44(37):3503-3626. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehad194

- 2.Ciarambino T, Menna G, Sansone G, Giordano M. Cardiomyopathies: An Overview. IJMS. 2021;22(14):7722. doi:10.3390/ijms22147722

- 3.2014 ESC Guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(39):2733-2779. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu284

- 4.Marian AJ, Braunwald E. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation Research. 2017;121(7):749-770. doi:10.1161/circresaha.117.311059

- 5.Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS, Maron BJ. New Perspectives on the Prevalence of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2015;65(12):1249-1254. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.019

- 6.Geske JB, Ommen SR, Gersh BJ. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. JACC: Heart Failure. 2018;6(5):364-375. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2018.02.010

- 7.Sabater‐Molina M, Pérez‐Sánchez I, Hernández del Rincón JP, Gimeno JR. Genetics of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A review of current state. Clinical Genetics. 2017;93(1):3-14. doi:10.1111/cge.13027

- 8.Antunes M de O, Scudeler TL. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. IJC Heart & Vasculature. 2020;27:100503. doi:10.1016/j.ijcha.2020.100503

- 9.Cardiology: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy . Royal College of Physicians. 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6399630/pdf/clinmed-19-1-61.pdf

- 10.Cao Y, Zhang PY. Review of recent advances in the management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2017;21(22):5207-5210. doi:10.26355/eurrev_201711_13841

- 11.Maron BJ, Desai MY, Nishimura RA, et al. Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2022;79(4):390-414. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.11.021

- 12.Mazzarotto F, Olivotto I, Boschi B, et al. Contemporary Insights Into the Genetics of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Toward a New Era in Clinical Testing? JAHA. 2020;9(8). doi:10.1161/jaha.119.015473

- 13.Harper AR, Goel A, Grace C, et al. Common genetic variants and modifiable risk factors underpin hypertrophic cardiomyopathy susceptibility and expressivity. Nat Genet. 2021;53(2):135-142. doi:10.1038/s41588-020-00764-0

- 14.Maron BJ, Maron MS, Wigle ED, Braunwald E. The 50-Year History, Controversy, and Clinical Implications of Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;54(3):191-200. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.069

- 15.O’Mahony C, Jichi F, Pavlou M, et al. A novel clinical risk prediction model for sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM Risk-SCD). European Heart Journal. 2013;35(30):2010-2020. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht439

- 16.McCully RB, Nishimura RA, Tajik AJ, Schaff HV, Danielson GK. Extent of Clinical Improvement After Surgical Treatment of Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1996;94(3):467-471. doi:10.1161/01.cir.94.3.467

- 17.Cardim N, Galderisi M, Edvardsen T, et al. Role of multimodality cardiac imaging in the management of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an expert consensus of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging Endorsed by the Saudi Heart Association. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16(3):280-280. doi:10.1093/ehjci/jeu291

- 18.Kim LK, Swaminathan RV, Looser P, et al. Hospital Volume Outcomes After Septal Myectomy and Alcohol Septal Ablation for Treatment of Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(3):324. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0252

- 19.Edelberg JM, Sehnert AJ, Mealiffe ME, del Rio CL, McDowell R. The Impact of Mavacamten on the Pathophysiology of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Narrative Review. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2022;22(5):497-510. doi:10.1007/s40256-022-00532-x

- 20.Maron MS, Masri A, Nassif ME, et al. Aficamten for Symptomatic Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(20):1849-1861. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2401424

- 21.Olivotto I, Oreziak A, Barriales-Villa R, et al. Mavacamten for treatment of symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (EXPLORER-HCM): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2020;396(10253):759-769. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31792-x

- 22.Mavacamten for treating symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy . The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta913/resources/mavacamten-for-treating-symptomatic-obstructive-hypertrophic-cardiomyopathy-pdf-82615485457861

- 23.Camzyos 10 mg hard capsules – Annex I Summary of Product Characteristics . Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2025. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/15029/smpc

- 24.Mavacamten: interactions . British National Formulary . 2025. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/interactions/mavacamten/