Shutterstock.com

By the end of this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the prevalence of migraine in the UK, its burden on individuals and economic impact;

- Understand the pathophysiology and stages of migraine and how it is diagnosed;

- Describe the main components of migraine treatment (lifestyle management, acute treatments, prophylactic agents), and the pharmacological and non-pharmacological options available to prescribers;

- Describe the mechanism of action for CGRP monoclonal antibodies and CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants).

Introduction

Headache is a common symptom associated with many different clinical conditions. The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) categorises headache into primary or secondary headache disorders1.

Primary headache disorders are not associated with another underlying condition. These headache disorders include migraine, tension-type headache, trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs) and ‘other’ (e.g. cough headache, primary stabbing headache, hypnic headache).

Secondary headache disorders are caused by another condition, such as trauma or injury to the head and/or neck, cranial or cervical vascular disorders, exposure to substances or substance withdrawal and infections1.

Migraine is characterised by recurrent episodes of moderate-to-severe headaches. They are usually unilateral but often bilateral in location, frequently pulsating, and aggravated by movement1,2. The symptoms most strongly associated with migraine headaches are nausea, disability (needing to stop any activity) and photophobia2,3. However, patients can also suffer from a wide range of different symptoms, such as phonophobia, motion sensitivity, visual disturbances, cognitive symptoms, numbness or tingling, dizziness, difficulty speaking, and fatigue1,2,4–9. While some symptoms can vary from person to person and even between different attacks, the cardinal features — as per the ICHD diagnostic criteria — remain the same10.

Migraine has two major types: migraine without aura and migraine with aura. The term ‘aura’ refers to the transient focal neurological symptoms that usually precede or sometimes accompany the headache1. Migraine can start at any age but usually appears in early adulthood11,12. It is a spectrum condition with severity and frequency of attacks varying throughout life, but often showing an improvement with age13,14.

Epidemiology

Migraine is the third most common health condition in the world, affecting approximately one in seven people globally1,15,16. It is more common than diabetes, asthma and epilepsy combined17. It is the second highest cause of global disability in the general population but takes first place in women aged 15–49 years18.

In the UK, it is estimated that approximately 10 million adults are living with migraine, with it affecting 1 in 4 adults aged 15–69 years19.

There is a big gender divide in migraine — it is two to three times more prevalent in women compared with men20. It is estimated that 24% of women in the UK are living with migraine compared with 12% of men19. Several factors are thought to contribute to the sex/gender disparity in migraine characteristics, including hormones, brain structure and function, and environmental aspects21–23.

Burden of migraine

Migraine can have a major negative impact on people’s work, family, and social lives2,19,24,25. Studies have shown that people living with migraine are more likely to have a variety of other long-term health conditions19,26. Emotional and mental health issues are also more prevalent in this patient group, with depression over 2.5 times and anxiety 2–5 times more likely to be present2,24.

Migraine also has a significant impact on the economy nationally, owing to its impact in the workplace, as well as direct healthcare costs. Approximately 2.5 million primary care appointments are linked to headaches and migraine per year; around 100,000 of which are referred to hospital for further assessment. The number of emergency hospital admissions for headaches and migraine attacks stood at 108,711 in 2018/201927.

It is estimated that migraine costs the UK economy between £6bn and £10bn per year, with indirect healthcare costs accounting for the majority of this28. Migraine-related absenteeism and presenteeism (reduced work productivity owing to being unwell) is estimated to be responsible for up to 86 million equivalent workdays lost per year in the UK. This loss of productivity equates to a cost of just under £8.8bn per annum29. Direct migraine-related healthcare costs are estimated to be up to £1bn per year29.

It should be understood that migraine is not ‘just a bad headache’.

Pathophysiology

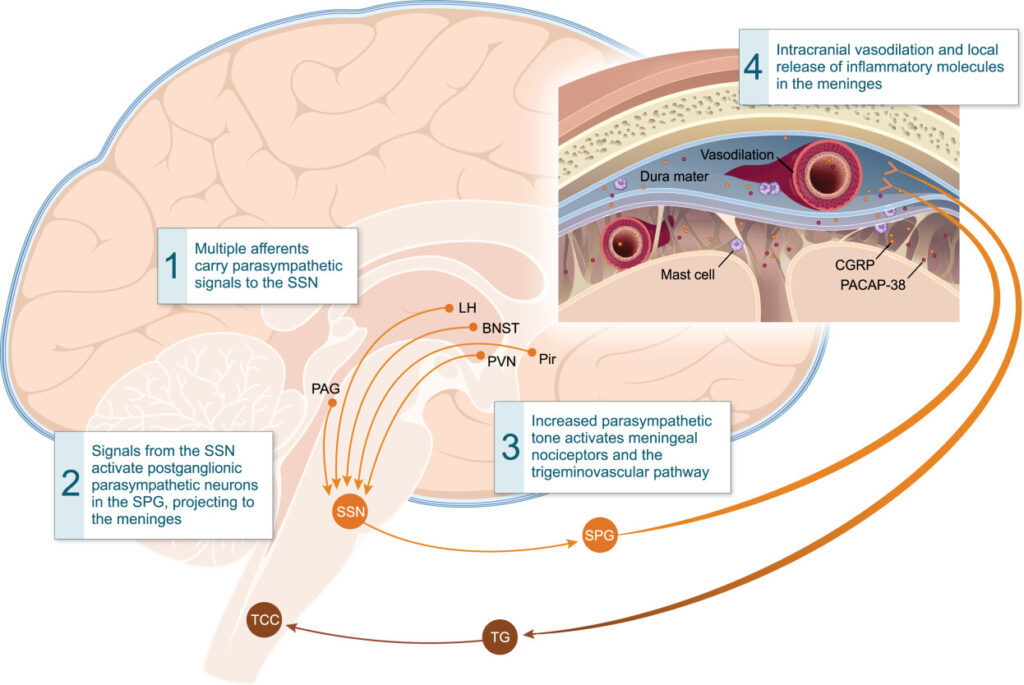

Migraine is a complex condition, and its mechanisms are not fully understood. For centuries, migraine was regarded as a vascular disorder owing to the throbbing nature of the pain30; however, it is now thought to originate from the trigeminovascular system and subsequently involve multiple components of both the peripheral and central nervous systems, across all phases of an attack31–35 (see Figure 136).

Activation of meningeal nociceptors by increased parasympathetic tone. BNST = bed nucleus of stria terminalis; LH = lateral hypothalamus; PAG = periaqueductal gray; Pir = piriform cortex; PVN = paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus; SPG = sphenopalatine ganglion; SSN = superior salivatory nucleus; TCC = trigeminal cervical complex; TG = trigeminal ganglion.

Reproduced with permission from Dodick, D.W. A Phase‐by‐Phase Review of Migraine Pathophysiology, Headache, Volume: 58, Issue: S1, Pages: 4-16

Four phases of a migraine attack have been identified: prodrome, aura, headache, and postdrome (30) (see Figure 21,2,5,8,13,27,35–52). A range of cognitive and physical symptoms have been reported before, during and after an attack5. It should be noted that not all migraine sufferers will experience every stage, nor all the symptoms of each stage, and that the stages can overlap37.

Visual representations of migraine aura can be seen in Box 1.53

Box 1: Visual representations of aura

Aura manifests in a highly individualised way and many migraine sufferers have attempted to visualise this through artwork. To see examples and more on this topic read: ‘In Aura: Migraine aura illustrations as online folk art’53.

For a patient perspective of migraine listen to The Pharmaceutical Journal‘s PJ Pod episode: ‘Changes in migraine treatment: how new classes of drugs can provide additional options for patients and prescribers.’

Neuropeptides

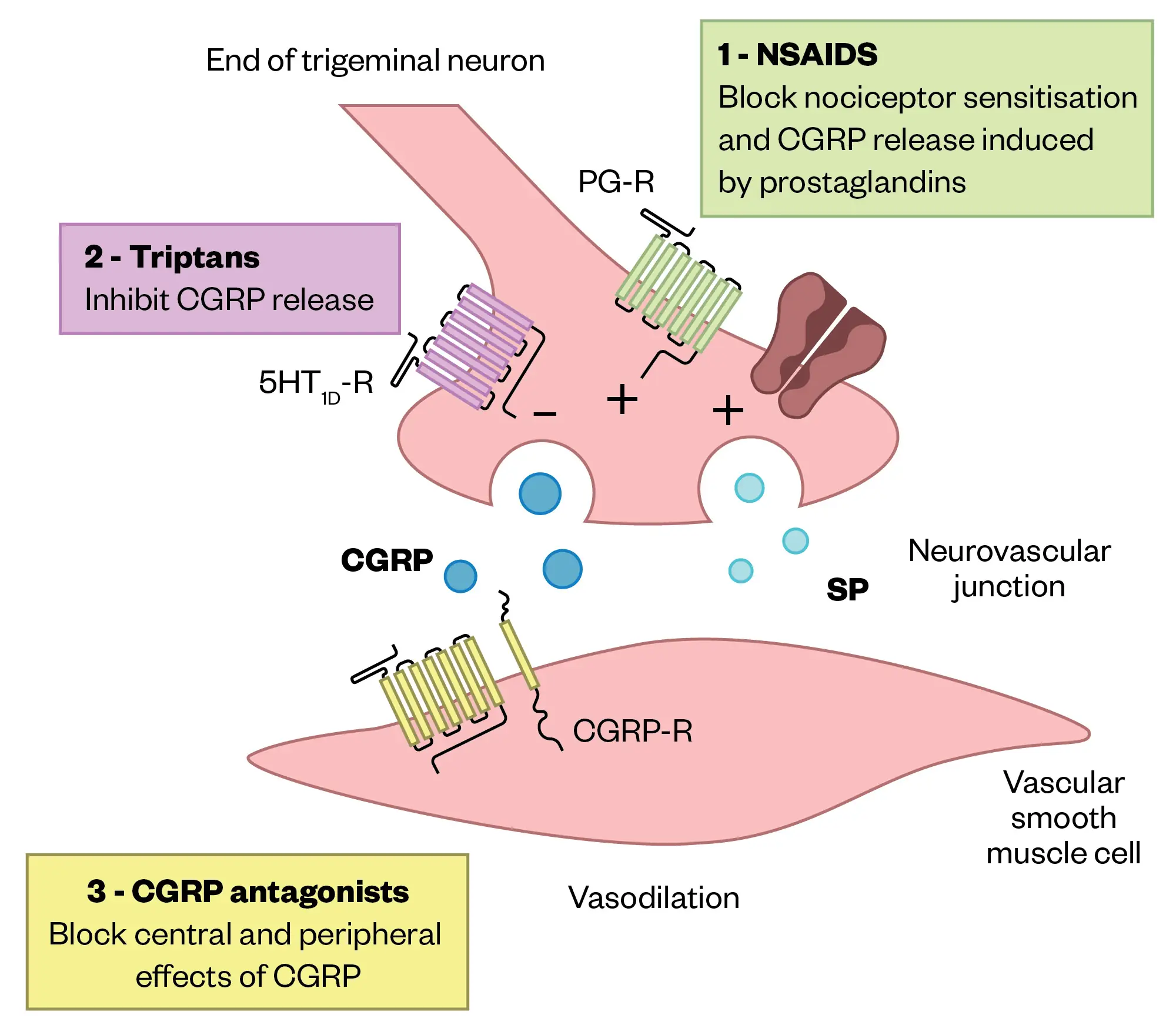

CGRP is a pain-signalling neuropeptide and potent vasodilator that is expressed throughout both the peripheral and central nervous system54,55. Activation of the trigeminal system results in the release of CGRP, which acts on vascular CGRP receptors to stimulate smooth muscle adenylyl cyclase, resulting in vasodilation54,56(see Figure 357).

CGRP receptors are also expressed elsewhere in the body. Inadvertently blocking CGRP at these locations could explain some of the reported adverse effects. For example, CGRP helps promote gastric acid secretion and aid gut motility, as well as having a potential role in hair growth and preventing hair loss. Inhibiting the action of CGRP in this area could explain the mechanism behind the adverse effects of constipation and alopecia, respectively58,59.

Levels of CGRP have been shown to be elevated in the plasma, saliva and tears of patients during migraine attacks55,60,61. Migraine patients also have higher background levels of CGRP than people without migraine62–64. Studies have demonstrated that when participants are given an infusion of CGRP they go on to develop a headache65,66.

CGRP, calcitonin gene-related peptide; SP, Substance P; PG-R, prostaglandin receptor

Adapted from Agostoni, et al

Triggers

Whilst the exact mechanism of what initiates a migraine attack is unknown, sufferers often report different factors that they believe can trigger an attack, or at least make one more likely to occur11,67. Many possible triggers have been reported, including9:

- Hormonal changes — menstruation;

- Emotional triggers — stress, anxiety, tension, shock, depression, excitement;

- Physical triggers — tiredness, poor-quality sleep, shift work, poor posture, neck or shoulder tension, jet lag, hypoglycaemia, strenuous exercise;

- Dietary triggers — missed/delayed/irregular meals, dehydration, alcohol, caffeine, chocolate, tyramine-containing food (e.g., cheese, yeast extract spread);

- Environmental triggers — bright lights, flickering screens, smoking, loud noises, changes in temp/humidity, strong smells;

- Medication — some sleeping tablets, combined contraceptive pill, HRT.

Sometimes it can be difficult to decide if something is a trigger or if what is being experienced (e.g. craving chocolate or cheese, feeling tired, etc) is simply a prodromal symptom of an attack already in progress35.

Diagnosis

First launched in 1988, the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) lists the standardised diagnostic criteria for the different types of migraine (see Figure 41). While resulting in a significant improvement in diagnostic accuracy and clinical research, it can be difficult to use in a clinical setting.

A thorough history is essential to diagnosing migraine. In 2003, a study by Lipton et al. demonstrated that asking headache sufferers three primary questions about the characteristics of their headache was a reliable way of diagnosing a migraine (see Box 2)3. The sensitivity and specificity of the questions were similar regardless of sex, age, the presence of other comorbid headaches, or previous diagnostic status.

Box 2: Effective diagnostic questions for migraine

During the past three months, did you have the following with your headaches?

- You felt nauseated or sick? (Yes/No)

- Light bothered you (a lot more than when you don’t have headaches)? (Yes/No)

- Your headaches limited your ability to work, study, or do what you needed to do? (Yes/No)

If a patient answers yes to two out of three of these questions, there is a 75% chance they have migraine.

Other characteristics of the migraine should also be noted and recorded, such as the pattern of the headaches, characteristics of the pain, any associated symptoms, presence of an aura, any associated triggers, family history, comorbidities, and medication and other treatments already tried8,11,37,68.

Table 1 is a comparative table to distinguish between some different headache types. It is based on the ICHD-3 diagnostic criteria1,2,69.

Episodic versus chronic migraine

Migraine can be further subcategorised into episodic migraine (EM) or chronic migraine (CM) based on the frequency of attacks (see Table 21,69,70).

While a threshold of 15 headache days to differentiate between episodic and chronic migraine seems somewhat arbitrary, population studies have shown that patients with chronic migraine are significantly more disabled than those with episodic migraine70.

An increase in the frequency of attacks, resulting in a progression from episodic to chronic migraine, is an example of chronification. Risk factors for chronification include female gender, increasing age, frequent episodic migraine attacks, medication overuse, high caffeine consumption and poor sleep, as well as comorbidities such as obesity, anxiety, depression and temporomandibular disorders71,72.

Classifying a migraine as episodic or chronic is also important from a medication management perspective. Some migraine treatments are only licensed in episodic migraine and some are only licensed in chronic migraine73,74.

While there is no minimum number of migraine days required for a diagnosis of episodic migraine, patients with episodic migraine must have a minimum of four migraine days/attacks per month to qualify for prophylactic treatment with current antimigraine therapies73,75–78.

Headache monitoring/scoring

There are several monitoring or scoring systems that can be used to record and assess migraine and its impact. Some of the more common systems are the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) and the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS), which quantify headache-related disability79,80. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) identifies depression and anxiety81.

An important part of migraine management is keeping a headache diary to document the frequency, duration, and severity of the headaches, any associated symptoms, what medication was self-administered and any potential triggers9,69. Headache diaries are an effective way of recording and identifying baseline headache patterns, as well as monitoring the effectiveness of an intervention. Historically paper-based, there are now several migraine tracking apps available (e.g. ‘Migraine Buddy’) that can make record-keeping easier and generate migraine-related analytics.

Referrals and red flags

The majority of headaches are primary headache disorders (e.g. migraine), but others are caused by another condition or disorder2. Serious causes of secondary headaches are rare (<1% of headache presentations)82.

Box 3 lists several red flags that suggest a potentially serious cause of secondary headache requiring emergency admission or urgent specialist referral2,83.

Box 3: Red flags for secondary headaches

- Age of over 50 years at onset of new headache;

- Current or recent pregnancy;

Characteristics:

- ‘Thunderclap’ headache (sudden onset and reaching maximum intensity within five minutes);

- Progressive or persistent headache (over days to weeks, particularly with focal neurological signs);

- Headache that has changed dramatically;

- Sudden onset precipitated by Valsalva manoeuvre (e.g. cough, sneeze, exertion, sex);

- Headache that worsens with lying or standing.

Additional features:

- Atypical or prolonged aura (duration >60 minutes, or including motor weakness, double vision, visual symptoms affecting only one eye, or impaired balance);

- Aura occurring for the first time in woman on combined oral contraceptive pill;

- Dizziness;

- New onset headache in a person with a history of cancer, human immunodeficiency virus, or immunosuppression;

- Signs of systemic illness (e.g. fever, neck stiffness, photophobia);

- Neurological signs (e.g. personality change, cognitive impairment);

- Seizures;

- Symptoms/signs of giant cell arteritis (age + e.g. jaw claudication);

- Contacts with similar symptoms.

Patients may have concerns about the likelihood of a serious cause for their headaches, such as a brain tumour. In the UK, approximately 1 in 7 people suffer from migraine, but the incidence of brain tumours is only 7 in 100,00084,85.

The likelihood of a headache having a serious underlying cause varies depending on where the patient presents. Approximately 0.1% of headaches identified in primary care, 1.0% of headaches identified in neurology clinics and 10% of headaches identified in emergency departments have a serious underlying cause85–87.

Treatments

The treatment of migraine is focused around three specific areas:

- Lifestyle management;

- Acute treatment;

- Prophylactic agents.

After the initial diagnosis of migraine is made, it is a good idea to try and manage patients’ expectations. While migraine cannot be cured, it can be effectively managed in most cases2.

Lifestyle management

The patient should be provided with information about their migraine to empower self-management2. This could be from a variety of support organisations or other reliable sources, such as the Migraine Trust, the National Migraine Centre with its ‘Heads Up’ podcast and the British Association for the Study of Headache (BASH).

In addition to identifying and avoiding migraine triggers, a change in lifestyle is an important part of migraine prevention69,88,89. A useful mnemonic for remembering the different areas of lifestyle management is ‘SEEDS’ (Sleep, Exercise, Eat, Diary and Stress)90:

- Sleep — good sleep hygiene, avoid too much or too little sleep;

- Exercise — regular exercise, at least 30 minutes three times a week;

- Eat — regular healthy meals, adequate hydration, low or stable caffeine intake;

- Diary — record frequency, duration, and severity of headaches;

- Stress — conflict avoidance, cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness, relaxation.

Acute treatment options

Clinicians can prescribe acute treatments in a stepped or stratified approach. In a stepped approach, treatment is slowly and only escalated after the first-line medicines have failed (i.e. simple analgesics prescribed initially, then escalated to include a triptan). With a stratified approach, the initial treatment is tailored to the severity of an attack2,91.

The first-line treatment options for a migraine attack are simple analgesics, triptans and anti-emetics. Domperidone, metoclopramide and prochlorperazine are the preferred anti-emetics owing to their multiple effects. In addition to treating the nausea and vomiting commonly associated with migraine, they also improve drug absorption by increasing gut motility, which counteracts the migraine-associated gastric stasis2,92–94.

Medication overuse headache (MOH) is a secondary headache that can develop as a consequence of using simple analgesics (e.g. aspirin, NSAIDs, paracetamol) for ≥15 days per month, or using triptans, opioids, ergots or combination analgesic medications for ≥10 days per month1,69,92. As a result, it is recommended that simple analgesics are limited to <15 days per month and triptans to <10 days per month2.

Opiates and compound analgesics should never be prescribed for treating a migraine attack owing to the significant risk of causing MOH and problems with dependency formation and withdrawal2,69. Attention should be paid to the contents of over-the-counter preparations that are marketed for migraine as they may contain codeine93.

Going ‘cold turkey’ and stopping all overused acute headache medication for at least one month can help to resolve the MOH by itself1,69, but other strategies can include starting regular prophylactic medication or offering short-term bridging treatments (e.g. nerve blocks or oral corticosteroids)95–97.

See Table 3 for BASH recommended acute treatment options for simple analgesics2.

The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has released drug safety updates for both domperidone and metoclopramide. Domperidone is contraindicated in cardiac disease and the maximum treatment duration should not usually exceed one week98. Metoclopramide should only be prescribed short-term use (up to five days) owing to the risk of neurological effects99.

Abortive agents

See Table 4 for some abortive agents for migraine2,100,101.

Triptans

Alongside simple analgesics, triptans are recommended treatment options for migraine attacks2. There are seven triptans licensed for migraine in England (sumatriptan, rizatriptan, zolmitriptan, eletriptan, almotriptan, naratriptan, and frovatriptan), with sumatriptan recommended as the first-line option by NICE92.

It should be noted that if a migraine attack is not responding to the initial dose of a triptan, a second dose should not be taken for the same attack100. If the triptan has not been effective within two hours, then it is unlikely to work during that attack; therefore, considering an alternative treatment option might be appropriate2.

If sumatriptan has been ineffective at managing a patient’s attack, the choice of which triptan to prescribe next should be guided by which feature is most important. When compared to sumatriptan 100mg, some of the newer triptans report lower adverse events (naratriptan 2.5mg, almotriptan 12.5mg, and frovatriptan 2.5mg), a better two-hour pain response (eletriptan 80mg, rizatriptan 10mg, and almotriptan 12.5mg), or a lower recurrence rate (frovatriptan 2.5mg and eletriptan 40mg and 80mg)2,102.

Triptans work by selectively binding to the serotonin receptors 5-HT1B/D/F, inhibiting the release of neuropeptides, and acting as vasoconstrictors in extracerebral arteries103–105 (see Figure 556).

Owing to the vasoconstrictive action of triptans, they are contraindicated in ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, previous myocardial infarction, and uncontrolled or severe hypertension2. Triptans are also unlicensed for people aged over 65 years because most of the trials excluded patients over 65 years100,106. While studies have shown that triptans do not directly increase vascular risk, they should be used with caution in older people (individuals aged over 50 years) owing to the increasing cardiovascular risk in this age group107,108.

Approximately 30% of patients do not respond to the triptan they are initially prescribed109. Owing to this, alternative triptans should be tried, as a lack of response to one triptan does not predict non-response to another2. A triptan should be trialled in at least three different attacks before being considered ineffective. A patient is deemed triptan-resistant if they are non-responsive to at least two triptans, and triptan refractory if they fail at least three triptans, including a subcutaneous formulation110.

Gepants

Small molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (‘gepants’) are part of the new class of migraine treatments that target CGRP. Unlike triptans, which directly cause vasoconstriction, gepants bind to the CGRP receptor, preventing the cascade that results in vasodilation and the subsequent headache pain. Only rimegepant is currently approved for use in England as an acute agent.

Rimegepant is an oral lyophilisate that should be placed on the tongue and allowed to dissolve. It reaches maximum concentration 1.5 hours after administration. While the side-effect profile is minimal, with only nausea and hypersensitivity listed, all suspected adverse reactions must be reported as it is still under the MHRA Black Triangle scheme.

No dose adjustments are required in renal impairment, but it should be avoided in end-stage renal disease owing to a lack of data. It should also be avoided in severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score C)101.

Rimegepant undergoes liver metabolism by CYP3A4 and CYP2C9, and it is also a substrate of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) efflux transporters. As a result, it has drug interactions with several moderate or strong inhibitors or inducers of these pathways, such as macrolide antibiotics, ‘azole’ antifungals, protease inhibitors, carbamazepine, diltiazem and rifampicin101,111.

Rimegepant has a licence for both acute usage and as prophylaxis in episodic migraine. As per NICE TA919, rimegepant is recommended as an option for the acute treatment of migraine, with or without aura in adults, only if for previous migraine attacks112:

- At least two triptans were tried and they did not work well enough; or

- Triptans were contraindicated or not tolerated, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and paracetamol were tried but did not work well enough.

The recommended dose of rimegepant is 75mg as needed (maximum 75mg per day)101. It would be advisable to monitor usage and, if the patient needs more than four doses per month, they should be considered for prophylactic treatment.

Contrary to triptans and NSAIDs, frequent use of gepants does not appear to cause MOH113.

Unlike the triptans, rimegepant is not contraindicated in patients who have had a myocardial infarction or stroke; however, the evidence regarding the safety of gepants after a stroke is not clear cut. While there is no evidence that gepants have direct vasoconstrictive effects114, they do prevent the CGRP-induced dilation of extracerebral arteries, which has the potential to cause a variety of cardiovascular pathophysiologies104,115. Furthermore, the main rimegepant clinical trials excluded patients who reported a cardiovascular event (such as a stroke or myocardial infarction) within the past six months114,116,117. Therefore, it would be prudent to avoid using rimegepant in the initial period following a stroke or myocardial infarction.

Medical devices

Alongside systemic treatment options, there are a range of medical devices available that may be beneficial in treating and/or preventing migraine symptoms118.

The Cefaly device is an external trigeminal nerve stimulator (e-TNS). It connects to an adhesive electrode that is placed on the forehead and generates micro-impulses to stimulate the trigeminal nerve and produce a sedative effect119. The treatment has been reviewed by NICE, which raised no major safety concerns, but stated that the evidence of effectiveness is limited for acute use and inadequate for prophylactic use120.

The sTMS mini device is a single pulse transcranial magnetic stimulator (sTMS). The device is placed against the back of the head and delivers a brief pre-set magnetic pulse. The pulse depolarises neurons in the brain, inhibiting cortical spreading depression, helping to treat a migraine attack118,121. NICE has recommended that transcranial magnetic stimulators should only be used under the care of a headache specialist, owing to a lack of evidence of efficacy, as well as uncertainty about the safety of long-term or frequent use122.

Prophylactic treatment options

Preventative treatment should be considered if a patient suffers from four or more migraine attacks per month, or if their migraine is having a significant impact on their quality of life2,92. The choice of prophylactic agent is patient specific. It is based on the side-effect profile and the patient’s pre-existing comorbidities. The medication is titrated slowly to effect, or to the highest tolerated dose2. Treatment is considered ineffective if there has been an inadequate response to the highest tolerated dose after two to three months of treatment92,123.

Table 5 provides some recommended pharmacological therapies that may be prescribed for migraine prophylaxis69,124. The doses recommended by BASH are normally higher than what is listed in the British National Formulary (BNF)2,92.

Some recommended non-pharmacological options include behavioural interventions (e.g. relaxation techniques or cognitive behavioural therapy), acupuncture or riboflavin 400mg daily2,69,125.

Other preventative options for which there is evidence include: lisinopril, sodium valproate, other Beta blockers (metoprolol, nadolol, timolol, and atenolol), flunarizine (not licensed in the UK), and oral supplements (co-enzyme Q10 and magnesium)2.

After a patient has tried and failed at least three of the standard preventative treatment options, they may be able to access more advanced migraine therapies either through their GP, secondary care or a headache specialist centre (see Table 673–75,78,126–130).

CGRP monoclonal antibodies

Like the Gepants, the ‘anti-CGRPs’ or CGRP monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are migraine-specific treatments that work by targeting CGRP. There are four anti-CGRPs currently available in the UK and, while they are broadly similar, they do have some interesting idiosyncrasies.

Erenumab (Aimovig; Novartis) targets the CGRP receptor, blocking CGRP from binding and preventing its action (125). Conversely, fremanezumab (Ajovy; Teva), galcanezumab (Emgality; Eli Lilly), and eptinezumab (Vyepti; H. Lundbeck) bind to the CGRP ligand itself127–129 (see Figure 556).

While there have not been any direct head-to-head studies comparing the effectiveness of different anti-CGRPs, two meta-analyses have suggested that fremanezumab is the most effective131,132; however, the studies disagree on whether this is statistically significant.

The anti-CGRPs have all received NICE approval for use in both episodic and chronic migraine. They are approved for use in patients only if75–78:

- They have four or more migraine days per month;

- They have tried and failed at least three preventative agents;

- The medication is provided as per the commercial agreement;

- For erenumab specifically, only the 140mg dose should be used.

NICE has mandated stopping criteria. After 12 weeks of treatment, patients with episodic migraine must show a ≥50% reduction in the number of headache days, and patients with chronic migraine must demonstrate a ≥30% reduction75–78. It is good practice to review the ongoing response to treatment regularly to ensure continued benefit.

Erenumab, fremanezumab and galcanezumab are all subcutaneous injections. They are normally administered once a month, although fremanezumab can be administered three-monthly when using the higher dose126–128. They are ideal products to be supplied via a homecare service, as they can easily be self-administered by patients in their own homes. Eptinezumab is given by intravenous infusion every three months129, which usually requires it to be administered in a hospital setting. As administration is only required four times per year, it means that hospital attendance for the infusion should be minimal. Another advantage is that the quarterly dosing may be beneficial in patients who struggle with treatment compliance.

A consideration that should be made when prescribing for women of childbearing age is whether there are any plans to become pregnant. Owing to a lack of data for the anti-CGRPs and gepants in pregnancy, a washout period should be recommended before planning a pregnancy. The washout period of the mAbs would be much longer than the gepants, owing to their significantly longer half-lives, which is approximately 1 month versus 11 hours, respectively101,126–129,133.

As with all medication, there will be cohorts of patients who do not respond to treatment. Unfortunately, there is currently no official guidance on whether a patient who fails one anti-CGRP can be switched to another125. However, some real-world studies have shown that patients who do not respond to a CGRP-receptor mAb (e.g. erenumab) may benefit from switching to a CGRP-ligand mAb (e.g. fremanezumab or galcanezumab,) and vice-versa134–137.

Switching between anti-CGRP mAbs is sometimes required owing to adverse effects. Most of the reported adverse effects for the anti-CGRPs include upper respiratory tract infection, nausea, constipation, injection site reactions and fatigue138. However, while the SmPC for erenumab lists an incidence rate of 3.2% for constipation as an adverse effect, real-world evidence has shown the actual incidence rate to be as high as 65%139,140. As a result, there should be a risk versus benefit discussion prior to initiating erenumab in patients with a history of constipation or other gastrointestinal motility issue.

Both erenumab devices contain natural rubber latex, which may cause severe allergic reactions, so should be avoided in patients with a latex allergy126. Neither the fremanezumab, galcanezumab or eptinezumab products contain latex127–129.

Gepants

As with the anti-CGRPs above, patients will normally need to have tried and failed several prophylactic agents before being able to try a gepant. Two gepants are currently licensed in England — rimegepant and atogepant — both of which are administered orally.

Rimegepant

Alongside its acute usage, rimegepant is also licensed for prophylaxis in episodic migraine. As per NICE TA906, rimegepant is recommended for preventing episodic migraine in adults who have 4–15 migraine attacks per month, only if at least three preventative treatments have failed73. Patients must be reviewed after 12 weeks of treatment and treatment stopped if the number of migraine attacks has not reduced by ≥50%. The recommended dose is 75mg on alternate days101.

Atogepant

As per NICE TA973, atogepant has been recommended for the prophylaxis of migraine in adults who have at least four migraine days per month and only if at least three preventative treatments have not worked. This means it can be prescribed for patients with both episodic and chronic migraine. Patients should be reviewed after 12 weeks of treatment and atogepant discontinued if the frequency of migraine attacks does not reduce by at least 50% for episodic migraine, or at least 30% for chronic migraine130.

Atogepant is a tablet that reaches maximum concentration within one to two hours after administration. The side-effect profile is minimal, with only nausea, constipation, decreased appetite and weight, and fatigue commonly reported. Increases in aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase were uncommon133.

The recommended dose of atogepant is 60mg once daily. Atogepant is metabolised by the liver, primarily by CYP3A4, and it is also a substrate of several transporters, including P-gp, BCRP, OATP1B1, OATP1B3 and OAT1. As a result, the dose should be reduced to 10mg once daily with concurrent use of strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g. ketoconazole, clarithromycin), strong OATP inhibitors (e.g. rifampicin, ciclosporin, telmisartan), or in poor renal function (creatinine clearance <30mL/minute). Atogepant should be avoided in severe hepatic impairment133,141.

In a similar fashion to rimegepant, both pivotal studies that investigated the effectiveness of atogepant in preventing migraine attacks excluded patients who had a myocardial infarction, stroke or transient ischemic attack within the previous six months142,143.

OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox)

Originally derived from the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, OnabotulinumtoxinA is a neurotoxin complex that causes localised paralysis by blocking the release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction144. It is thought to work in chronic migraine by blocking the release of vesicles that contain pro-inflammatory and excitatory neuropeptides and neurotransmitters that are involved in migraine, such as substance P, CGRP, PACAP (pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide), glutamate and amylin145.

Several brands of OnabotulinumtoxinA are available; however, only Botox is licensed to treat chronic migraine. Botulinum toxin units are not interchangeable from one product to another144,146–152. Botox has undergone a NICE technology appraisal and is recommended as an option for the prophylaxis of chronic migraine when patients have not responded to at least three prophylactic agents and medication overuse headache has been effectively managed. Treatment should be stopped if patients do not demonstrate a ≥30% reduction in headache days after two cycles, or if they revert to episodic migraine for three consecutive months74.

Botox is not licensed for episodic migraine as the initial trials showed no statistically significant improvement in the number of migraine days between treated and placebo groups153,154.

To treat chronic migraine, a total dose of 155–195 units of Botox is administered intramuscularly across 31–39 sites around the head and back of the neck, with a recommended re-treatment schedule of every 12 weeks144,155. The Botox injections are reasonably well tolerated. Side effects are minimal and include temporary neck pain, headache, muscle weakness and ptosis (eyelid droop)156. The ptosis is reversible and normally wears off over time.

Several studies have reported that using a combination of Botox, alongside an anti-CGRP, enhances the overall efficacy and results in a further reduction in the number of headache days, compared with using either as a single agent157. However, in both 2019 and 2022, the European Headache Federation could not recommend this practice owing to a lack of data158,159.

Peripheral nerve blocks

Other injectable treatments that may be offered by a specialist clinic include a variety of peripheral nerve blocks. These involve injecting a local anaesthetic, with or without steroid, to specific nerves around the head156. If a steroid-containing formulation is used, there is the risk of scarring and hair loss at the injection site, although this is rare160.

Conclusion

Migraine is a source of significant morbidity for patients, and there is a need for an individualised and holistic approach to management of the condition. Pharmacists across sectors can support this patient group by recognising the symptoms of migraine, understanding how it can be distinguished from other headaches types and being aware of the approved treatment options, including the latest developments.

- 1.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1-211. doi:10.1177/0333102417738202

- 2.Ahmed F, Bahra A, Tyaqi A, Weatherby S. National Headache Management System for Adults 2019. British Association for the Study of Headache. 2019. Accessed October 2024. https://headache.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/bash-guideline-2019.pdf

- 3.Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky R, et al. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care. Neurology. 2003;61(3):375-382. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000078940.53438.83

- 4.Houtveen JH, Sorbi MJ. Prodromal Functioning of Migraine Patients Relative to Their Interictal State – An Ecological Momentary Assessment Study. Sommer C, ed. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e72827. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072827

- 5.Giffin NJ, Ruggiero L, Lipton RB, et al. Premonitory symptoms in migraine. Neurology. 2003;60(6):935-940. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000052998.58526.a9

- 6.Kelman L. The Postdrome of the Acute Migraine Attack. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(2):214-220. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01026.x

- 7.Giffin NJ, Lipton RB, Silberstein SD, Olesen J, Goadsby PJ. The migraine postdrome. Neurology. 2016;87(3):309-313. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000002789

- 8.What are the clinical features and diagnostic criteria for migraine? National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2022. Accessed October 2024. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/migraine/diagnosis/diagnosis

- 9.Migraine. NHS Inform. 2023. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/brain-nerves-and-spinal-cord/migraine/

- 10.The Timeline of a Migraine Attack. American Migraine Foundation. 2018. Accessed October 2024. https://americanmigrainefoundation.org/resource-library/timeline-migraine-attack/#:~:text=Headache%20phase%20pain%20can%20vary,with%20migraine%20during%20this%20phase

- 11.Migraine. NHS. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/migraine/

- 12.Kuan V, Denaxas S, Gonzalez-Izquierdo A, et al. A chronological map of 308 physical and mental health conditions from 4 million individuals in the English National Health Service. The Lancet Digital Health. 2019;1(2):e63-e77. doi:10.1016/s2589-7500(19)30012-3

- 13.Kelman L. Migraine Changes with Age: IMPACT on Migraine Classification. Headache. 2006;46(7):1161-1171. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00444.x

- 14.Brennan KC, Pietrobon D. A Systems Neuroscience Approach to Migraine. Neuron. 2018;97(5):1004-1021. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.029

- 15.Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Birbeck GL. Migraine: the seventh disabler. J Headache Pain. 2013;14(1). doi:10.1186/1129-2377-14-1

- 16.Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ. Global epidemiology of migraine and its implications for public health and health policy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2023;19(2):109-117. doi:10.1038/s41582-022-00763-1

- 17.Headache Disorders – not respected, not resourced. All-Party Parliamentary Group on Primary Headache Disorders. 2023. Accessed October 2024. https://migrainetrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/APPGPHD-Report-on-Headache-Services-in-England-–-Full-Report.pdf

- 18.Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Jensen R, Uluduz D, Katsarava Z. Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-020-01208-0

- 19.Who is living with migraine in the UK? The Migraine Trust. Accessed October 2024. https://migrainetrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/State-of-the-Migraine-Nation-population-rapid-review.pdf

- 20.Vetvik KG, MacGregor EA. Sex differences in the epidemiology, clinical features, and pathophysiology of migraine. The Lancet Neurology. 2017;16(1):76-87. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(16)30293-9

- 21.Rossi MF, Tumminello A, Marconi M, et al. Sex and gender differences in migraines: a narrative review. Neurol Sci. 2022;43(9):5729-5734. doi:10.1007/s10072-022-06178-6

- 22.Allais G, Chiarle G, Sinigaglia S, Airola G, Schiapparelli P, Benedetto C. Gender-related differences in migraine. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(S2):429-436. doi:10.1007/s10072-020-04643-8

- 23.Al-Hassany L, Haas J, Piccininni M, Kurth T, Maassen V, Rohmann J. Giving Researchers a Headache – Sex and Gender Differences in Migraine. Front Neurol. 2020;11:549038. doi:10.3389/fneur.2020.549038

- 24.Minen MT, Begasse De Dhaem O, Kroon Van Diest A, et al. Migraine and its psychiatric comorbidities. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(7):741-749. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2015-312233

- 25.Begasse de Dhaem O, Sakai F. Migraine in the workplace. eNeurologicalSci. 2022;27:100408. doi:10.1016/j.ensci.2022.100408

- 26.Dresler T, Caratozzolo S, et al. Understanding the nature of psychiatric comorbidity in migraine: a systematic review focused on interactions and treatment implications. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-019-0988-x

- 27.Improved NHS migraine care to save thousands of hospital stays. NHS England. 2020. Accessed October 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2020/01/improved-nhs-migraine-care/#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20admissions%20to,emergency%20admissions%20in%202018%2F19

- 28.Dismissed for too long: Recommendations to improve migraine care in the UK. The Migraine Trust. September 2021. Accessed October 2024. https://migrainetrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Dismissed-for-too-long_Recommendations-to-improve-migraine-care-in-the-UK.pdf

- 29.Society’s headache: The socioeconomic impact of migraine. The Work Foundation, University of Lancaster. April 2018. Accessed October 2024. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/lums/work-foundation/SocietysHeadacheTheSocioeconomicimpactofmigraine.pdf

- 30.Charles A. The Evolution of a Migraine Attack – A Review of Recent Evidence. Headache. 2012;53(2):413-419. doi:10.1111/head.12026

- 31.Burstein R, Noseda R, Borsook D. Migraine: Multiple Processes, Complex Pathophysiology. J Neurosci. 2015;35(17):6619-6629. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0373-15.2015

- 32.Edvinsson L, Tajti J, Szalárdy L, Vécsei L. PACAP and its role in primary headaches. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-018-0852-4

- 33.Tajti J, Szok D, Majláth Z, Tuka B, Csáti A, Vécsei L. Migraine and neuropeptides. Neuropeptides. 2015;52:19-30. doi:10.1016/j.npep.2015.03.006

- 34.Russo AF. Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP): A New Target for Migraine. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;55(1):533-552. doi:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124701

- 35.Goadsby PJ, Holland PR, Martins-Oliveira M, Hoffmann J, Schankin C, Akerman S. Pathophysiology of Migraine: A Disorder of Sensory Processing. Physiological Reviews. 2017;97(2):553-622. doi:10.1152/physrev.00034.2015

- 36.Dodick DW. A Phase‐by‐Phase Review of Migraine Pathophysiology. Headache. 2018;58(S1):4-16. doi:10.1111/head.13300

- 37.Stages of a migraine attack . The Migraine Trust. Accessed October 2024. https://migrainetrust.org/understand-migraine/stages-of-a-migraine-attack/#:~:text=stop%20their%20attack.-,Recovery%20or%20Postdrome%20stage,Often%2C%20they%20mirror%20these%20symptoms

- 38.Migraine Stages. Advanced Headache Center. 2023. Accessed October 2024. https://www.advancedheadachecenter.com/migraines/migraine-stages

- 39.Eigenbrodt AK, Christensen RH, Ashina H, et al. Premonitory symptoms in migraine: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies reporting prevalence or relative frequency. J Headache Pain. 2022;23(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-022-01510-z

- 40.Laurell K, Artto V, Bendtsen L, et al. Premonitory symptoms in migraine: A cross-sectional study in 2714 persons. Cephalalgia. 2016;36(10):951-959. doi:10.1177/0333102415620251

- 41.Schoonman G, Evers D, Terwindt G, van Dijk J, Ferrari M. The Prevalence of Premonitory Symptoms in Migraine: A Questionnaire Study in 461 Patients. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(10):1209-1213. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01195.x

- 42.May A, Burstein R. Hypothalamic regulation of headache and migraine. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(13):1710-1719. doi:10.1177/0333102419867280

- 43.Alstadhaug K. Migraine and the Hypothalamus. Cephalalgia. 2009;29(8):809-817. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01814.x

- 44.Barbanti P, Aurilia C, Egeo G, Fofi L, Guadagni F, Ferroni P. Dopaminergic symptoms in migraine: A cross-sectional study on 1148 consecutive headache center-based patients. Cephalalgia. 2020;40(11):1168-1176. doi:10.1177/0333102420929023

- 45.Bigal ME, Liberman JN, Lipton RB. Age-dependent prevalence and clinical features of migraine. Neurology. 2006;67(2):246-251. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000225186.76323.69

- 46.Liu GT, Volpe NJ, Galetta SL. Visual Hallucinations and Illusions. Liu, Volpe, and Galetta’s Neuro-Ophthalmology. Published online 2019:395-413. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-34044-1.00012-2

- 47.Thomsen AV, Ashina H, Al-Khazali HM, et al. Clinical features of migraine with aura: a REFORM study. J Headache Pain. 2024;25(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-024-01718-1

- 48.Russell MB, Olesen J. A nosographic analysis of the migraine aura in a general population. Brain. 1996;119(2):355-361. doi:10.1093/brain/119.2.355

- 49.Eriksen M, Thomsen L, Andersen I, Nazim F, Olesen J. Clinical Characteristics of 362 Patients with Familial Migraine with Aura. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(7):564-575. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00718.x

- 50.Viana M, Sances G, Linde M, et al. Clinical features of migraine aura: Results from a prospective diary-aided study. Cephalalgia. 2016;37(10):979-989. doi:10.1177/0333102416657147

- 51.Viana M, Tronvik EA, Do TP, Zecca C, Hougaard A. Clinical features of visual migraine aura: a systematic review. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-019-1008-x

- 52.Leao A. Spreading Depression of Activity in the Cerebral Cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1944;7(6):359-390. https://www.google.com/search?q=Journal+of+Neurophysiology+abbreviation&client=safari&sca_esv=640dfa46d8859720&rls=en&sxsrf=ADLYWILgsfSjKnxF1WSJJJAizXKaKgoloQ%3A1729853927709&ei=53kbZ9r6Ku-BhbIPsZPIsQE&ved=0ahUKEwiaiv-GsKmJAxXvQEEAHbEJMhYQ4dUDCBA&uact=5&oq=Journal+of+Neurophysiology+abbreviation&gs_lp=Egxnd3Mtd2l6LXNlcnAiJ0pvdXJuYWwgb2YgTmV1cm9waHlzaW9sb2d5IGFiYnJldmlhdGlvbjIGEAAYCBgeMgsQABiABBiGAxiKBTIIEAAYgAQYogQyCBAAGIAEGKIESO4CUABYAHAAeAGQAQCYAXWgAXWqAQMwLjG4AQPIAQD4AQL4AQGYAgGgAnqYAwCSBwMwLjGgB5YD&sclient=gws-wiz-serp

- 53.In Aura – Migraine aura illustrations as online folk art. Medium. 2014. https://medium.com/message/in-aura-aa069cfa47f8

- 54.Edvinsson L, Warfvinge K. Recognizing the role of CGRP and CGRP receptors in migraine and its treatment. Cephalalgia. 2017;39(3):366-373. doi:10.1177/0333102417736900

- 55.Ho TW, Edvinsson L, Goadsby PJ. CGRP and its receptors provide new insights into migraine pathophysiology. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6(10):573-582. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2010.127

- 56.Edvinsson L, Haanes KA, Warfvinge K, Krause DN. CGRP as the target of new migraine therapies — successful translation from bench to clinic. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(6):338-350. doi:10.1038/s41582-018-0003-1

- 57.Agostoni EC, Barbanti P, et al. Current and emerging evidence-based treatment options in chronic migraine: a narrative review. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-019-1038-4

- 58.Ailani J, Kaiser EA, Mathew PG, et al. Role of Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide on the Gastrointestinal Symptoms of Migraine—Clinical Considerations. Neurology. 2022;99(19):841-853. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000201332

- 59.Ruiz M, Cocores A, Tosti A, Goadsby PJ, Monteith TS. Alopecia as an emerging adverse event to CGRP monoclonal antibodies: Cases Series, evaluation of FAERS, and literature review. Cephalalgia. 2023;43(2). doi:10.1177/03331024221143538

- 60.Wattiez AS, Sowers LP, Russo AF. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP): role in migraine pathophysiology and therapeutic targeting. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 2020;24(2):91-100. doi:10.1080/14728222.2020.1724285

- 61.Schuster NM, Rapoport AM. New strategies for the treatment and prevention of primary headache disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(11):635-650. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2016.143

- 62.Kamm K, Straube A, Ruscheweyh R. Calcitonin gene-related peptide levels in tear fluid are elevated in migraine patients compared to healthy controls. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(12):1535-1543. doi:10.1177/0333102419856640

- 63.Cernuda-Morollón E, Larrosa D, Ramón C, Vega J, Martínez-Camblor P, Pascual J. Interictal increase of CGRP levels in peripheral blood as a biomarker for chronic migraine. Neurology. 2013;81(14):1191-1196. doi:10.1212/wnl.0b013e3182a6cb72

- 64.van Dongen RM, Zielman R, Noga M, et al. Migraine biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia. 2016;37(1):49-63. doi:10.1177/0333102415625614

- 65.Hansen JM, Hauge AW, Olesen J, Ashina M. Calcitonin gene-related peptide triggers migraine-like attacks in patients with migraine with aura. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(10):1179-1186. doi:10.1177/0333102410368444

- 66.Lassen L, Haderslev P, Jacobsen V, Iversen H, Sperling B, Olesen J. Cgrp May Play A Causative Role in Migraine. Cephalalgia. 2002;22(1):54-61. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00310.x

- 67.Migraine attack triggers. The Migraine Trust. Accessed October 2024. https://migrainetrust.org/live-with-migraine/self-management/common-triggers/

- 68.Lateef TM, Cui L, Nakamura E, Dozier J, Merikangas K. Accuracy of Family History Reports of Migraine in a Community‐Based Family Study of Migraine. Headache. 2015;55(3):407-412. doi:10.1111/head.12501

- 69.Headaches in over 12s: diagnosis and management Clinical guideline [CG150]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. September 2012. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg150

- 70.Katsarava Z, Buse DC, Manack AN, Lipton RB. Defining the Differences Between Episodic Migraine and Chronic Migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;16(1):86-92. doi:10.1007/s11916-011-0233-z

- 71.Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Migraine Chronification. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2011;11(2):139-148. doi:10.1007/s11910-010-0175-6

- 72.Torres-Ferrús M, Ursitti F, et al. From transformation to chronification of migraine: pathophysiological and clinical aspects. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-020-01111-8

- 73.Rimegepant for preventing migraine, Technology appraisal guidance: TA906. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. July 2023. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta906

- 74.Botulinum toxin type A for the prevention of headaches in adults with chronic migraine, Technology appraisal guidance: TA260. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. June 2012. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta260

- 75.Erenumab for preventing migraine, Technology appraisal guidance: TA682. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. March 2021. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta682

- 76.Fremanezumab for preventing migraine, Technology appraisal guidance: TA764. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. February 2022. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta764

- 77.Galcanezumab for preventing migraine, Technology appraisal guidance: TA659. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. November 2020. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta659

- 78.Eptinezumab for preventing migraine, Technology appraisal guidance: TA871. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. March 2023. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta871

- 79.Yang M, Rendas-Baum R, Varon SF, Kosinski M. Validation of the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6TM) across episodic and chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2010;31(3):357-367. doi:10.1177/0333102410379890

- 80.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner KB, Sawyer J, Lee C, Liberman JN. Validity of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score in comparison to a diary-based measure in a population sample of migraine sufferers. Pain. 2000;88(1):41-52. doi:10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00305-5

- 81.Stern AF. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Occupational Medicine. 2014;64(5):393-394. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqu024

- 82.Steiner TJ, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, et al. Aids to management of headache disorders in primary care (2nd edition). J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-018-0899-2

- 83.Scenario: Headache – diagnosis. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. March 2022. Accessed October 2024. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/headache-assessment/diagnosis/headache-diagnosis/

- 84.Steiner T, Scher A, Stewart W, Kolodner K, Liberman J, Lipton R. The Prevalence and Disability Burden of Adult Migraine in England and their Relationships to Age, Gender and Ethnicity. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(7):519-527. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00568.x

- 85.Hamilton W, Kernick D. Clinical features of primary brain tumours: a case-control study using electronic primary care records. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(542):695-699. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17761056

- 86.Schankin C, Ferrari U, Reinisch V, Birnbaum T, Goldbrunner R, Straube A. Characteristics of Brain Tumour-Associated Headache. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(8):904-911. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01368.x

- 87.Locker TE, Thompson C, Rylance J, Mason SM. The Utility of Clinical Features in Patients Presenting With Nontraumatic Headache: An Investigation of Adult Patients Attending an Emergency Department. Headache. 2006;46(6):954-961. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00448.x

- 88.Agbetou M, Adoukonou T. Lifestyle Modifications for Migraine Management. Front Neurol. 2022;13. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.719467

- 89.Headache hygiene: what is it? American Migraine Foundation. Accessed October 2024. https://americanmigrainefoundation.org/resource-library/what-is-headache-hygiene/#:~:text=Go%20to%20sleep%20and%20wake,eat%20a%20good%2C%20healthy%20breakfast

- 90.Robblee J, Starling AJ. SEEDS for success: Lifestyle management in migraine. CCJM. 2019;86(11):741-749. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.19009

- 91.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Stone AM, Láinez MJA, Sawyer JPC. Stratified Care vs Step Care Strategies for Migraine. JAMA. 2000;284(20):2599. doi:10.1001/jama.284.20.2599

- 92.Scenario: Migraine in adults. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. September 2024. Accessed October 2024. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/migraine/management/adults/

- 93.Acute medicines. The Migraine Trust. Accessed October 2024. https://migrainetrust.org/live-with-migraine/healthcare/treatments/acute-medicines/

- 94.Aurora SK, Kori SH, Barrodale P, McDonald SA, Haseley D. Gastric Stasis in Migraine: More Than Just a Paroxysmal Abnormality During a Migraine Attack. Headache. 2006;46(1):57-63. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00311.x

- 95.Dodick D, Freitag F. Evidence‐Based Understanding of Medication‐Overuse Headache: Clinical Implications. Headache. 2006;46(s4). doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00604.x

- 96.Diener HC, Antonaci F, Braschinsky M, et al. European Academy of Neurology guideline on the management of medication‐overuse headache. Euro J of Neurology. 2020;27(7):1102-1116. doi:10.1111/ene.14268

- 97.Gosalia H, Moreno-Ajona D, Goadsby PJ. Medication-overuse headache: a narrative review. J Headache Pain. 2024;25(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-024-01755-w

- 98.Domperidone. British National Formulary. Accessed October 2024. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/domperidone

- 99.Metoclopramide hydrochloride. British National Formulary. Accessed October 2024. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/metoclopramide-hydrochloride/#:~:text=Usual%20dose%20is%2010%20mg,syringe%20to%20ensure%20dose%20accuracy.

- 100.sumatriptan. doi:10.18578/bnf.791549275

- 101.VYDURA 75 mg oral lyophilisate. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/13928/smpc

- 102.Ferrari MD, Roon KI, Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ. Oral triptans (serotonin 5-HT1B/1D agonists) in acute migraine treatment: a meta-analysis of 53 trials. The Lancet. 2001;358(9294):1668-1675. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06711-3

- 103.Mason BN, Russo AF. Vascular Contributions to Migraine: Time to Revisit? Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12. doi:10.3389/fncel.2018.00233

- 104.Benemei S, Cortese F, et al. Triptans and CGRP blockade – impact on the cranial vasculature. J Headache Pain. 2017;18(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-017-0811-5

- 105.Gazda S. Headaches & long COVID – how we treat ongoing symptoms. Suzanne Gazda MD. June 2022. Accessed October 2024. https://www.suzannegazdamd.com/blog—long-covid/headaches-long-covid-how-we-treat-ongoing-symptoms

- 106.Haan J, Hollander J, Ferrari M. Migraine in The Elderly: A Review. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(2):97-106. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01250.x

- 107.Zebenholzer K, Gall W, Gleiss A, Pavelic AR, Wöber C. Triptans and vascular comorbidity in persons over fifty: Findings from a nationwide insurance database – A cohort study. Headache. 2022;62(5):604-612. doi:10.1111/head.14304

- 108.Rajati F, Rajati M, Rasulehvandi R, Kazeminia M. Prevalence of stroke in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Interdisciplinary Neurosurgery. 2023;32:101746. doi:10.1016/j.inat.2023.101746

- 109.Dahlöf C. Infrequent or Non-Response to Oral Sumatriptan does not Predict Response to Other Triptans—Review of Four Trials. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(2):98-106. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01010.x

- 110.Sacco S, Lampl C, Amin FM, et al. European Headache Federation (EHF) consensus on the definition of effective treatment of a migraine attack and of triptan failure. J Headache Pain. 2022;23(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-022-01502-z

- 111.Rimegepant. British National Formulary. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_608179422?hspl=Rimegepant

- 112.Rimegepant for treating migraine (TA919). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta919

- 113.Lo Castro F, Guerzoni S, Pellesi L. Safety and Risk of Medication Overuse Headache in Lasmiditan and Second-Generation Gepants: A Rapid Review. DHPS. 2021;Volume 13:233-240. doi:10.2147/dhps.s304373

- 114.Marcus R, Goadsby PJ, Dodick D, Stock D, Manos G, Fischer TZ. BMS-927711 for the acute treatment of migraine: A double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled, dose-ranging trial. Cephalalgia. 2013;34(2):114-125. doi:10.1177/0333102413500727

- 115.MaassenVanDenBrink A, Meijer J, Villalón CM, Ferrari MD. Wiping Out CGRP: Potential Cardiovascular Risks. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2016;37(9):779-788. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2016.06.002

- 116.Croop R, Goadsby PJ, Stock DA, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of rimegepant orally disintegrating tablet for the acute treatment of migraine: a randomised, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2019;394(10200):737-745. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31606-x

- 117.Lipton RB, Croop R, Stock EG, et al. Rimegepant, an Oral Calcitonin Gene–Related Peptide Receptor Antagonist, for Migraine. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(2):142-149. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1811090

- 118.Medical devices. The Migraine Trust. Accessed October 2024. https://migrainetrust.org/live-with-migraine/healthcare/treatments/medical-devices/

- 119.How does Cefaly work? Cefaly . Accessed October 2024. https://www.cefaly.co.uk/en/how-it-works

- 120.Transcutaneous electrical stimulation of the supraorbital nerve for treating and preventing migraine, Interventional procedures guidance [IPG740]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. October 2022. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg740

- 121.Bhola R, Kinsella E, Giffin N, et al. Single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (sTMS) for the acute treatment of migraine: evaluation of outcome data for the UK post market pilot program. J Headache Pain. 2015;16(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-015-0535-3

- 122.Transcranial magnetic stimulation for treating and preventing migraine, Interventional procedures guidance [IPG477]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. January 2014. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg477

- 123.Sacco S, Braschinsky M, Ducros A, et al. European headache federation consensus on the definition of resistant and refractory migraine. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-020-01130-5

- 124.Candesartan cilexetil. British National Formulary. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_790958181?hspl=Candesartan%20cilexetil

- 125.Pharmacological management of migraine – SIGN155. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Accessed October 2024. https://www.sign.ac.uk/sign-155-migraine

- 126.Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd. Aimovig 70 mg solution for injection in pre-filled pen. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/9380/smpc

- 127.Ajovy (fremanezumab) 225 mg Pre-filled Syringe for Injection. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11630/smpc

- 128.Emgality 120 mg solution for injection in pre-filled pen. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/10478/smpc

- 129.VYEPTI 100 mg concentrate for solution for infusion. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/13243/smpc

- 130.Atogepant for preventing migraine, Technology appraisal guidance: TA973. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. May 2024. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta973

- 131.Lampl C, MaassenVanDenBrink A, Deligianni CI, et al. The comparative effectiveness of migraine preventive drugs: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Headache Pain. 2023;24(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-023-01594-1

- 132.Soni P, Chawla E. Efficacy and safety of anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibodies for treatment of chronic migraine: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2021;209:106893. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2021.106893

- 133.AQUIPTA 60 mg tablets. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/15049/smpc

- 134.Overeem LH, Lange KS, Fitzek MP, et al. Effect of switching to erenumab in non-responders to a CGRP ligand antibody treatment in migraine: A real-world cohort study. Front Neurol. 2023;14. doi:10.3389/fneur.2023.1154420

- 135.Talbot J, Stuckey R, Wood N, Gordon A, Crossingham G, Weatherby S. Switching anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in chronic migraine: real-world observations of erenumab, fremanezumab and galcanezumab. Eur J Hosp Pharm. Published online January 5, 2024:ejhpharm-2023-003779. doi:10.1136/ejhpharm-2023-003779

- 136.Overeem LH, Peikert A, Hofacker MD, et al. Effect of antibody switch in non-responders to a CGRP receptor antibody treatment in migraine: A multi-center retrospective cohort study. Cephalalgia. 2021;42(4-5):291-301. doi:10.1177/03331024211048765

- 137.Patier Ruiz I, Sánchez-Rubio Ferrández J, Cárcamo Fonfría A, Molina García T. Early Experiences in Switching between Monoclonal Antibodies in Patients with Nonresponsive Migraine in Spain: A Case Series. Eur Neurol. 2021;85(2):132-135. doi:10.1159/000518899

- 138.Aditya S, Rattan A. Advances in CGRP Monoclonal Antibodies as Migraine Therapy. Saudi Journal of Medicine & Medical Sciences. 2023;11(1):11-18. doi:10.4103/sjmms.sjmms_95_22

- 139.de Vries Lentsch S, Verhagen IE, van den Hoek TC, MaassenVanDenBrink A, Terwindt GM. Treatment with the monoclonal calcitonin gene‐related peptide receptor antibody erenumab: A real‐life study. Euro J of Neurology. 2021;28(12):4194-4203. doi:10.1111/ene.15075

- 140.Holzer P, Holzer-Petsche U. Constipation Caused by Anti-calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Migraine Therapeutics Explained by Antagonism of Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide’s Motor-Stimulating and Prosecretory Function in the Intestine. Front Physiol. 2022;12. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.820006

- 141.Atogepant. British National Formulary. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/bnf/_638974777?hspl=Atogepant.

- 142.Ailani J, Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ, et al. Atogepant for the Preventive Treatment of Migraine. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(8):695-706. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2035908

- 143.Pozo-Rosich P, Ailani J, Ashina M, et al. Atogepant for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine (PROGRESS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2023;402(10404):775-785. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(23)01049-8

- 144.BOTOX 100 Allergan Units Powder for solution for injection. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/859/smpc

- 145.Burstein R, Blumenfeld AM, Silberstein SD, Manack Adams A, Brin MF. Mechanism of Action of OnabotulinumtoxinA in Chronic Migraine: A Narrative Review. Headache. 2020;60(7):1259-1272. doi:10.1111/head.13849

- 146.Alluzience, 200 Speywood units/ml, solution for injection. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/13798/smpc

- 147.Azzalure, 125 Speywood units, powder for solution for injection. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6584/smpc

- 148.BOCOUTURE 100 units powder for solution for injection. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/7418/smpc

- 149.Letybo 50 units powder for solution for injection. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/13707/smpc

- 150.Nuceiva. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/14178/smpc

- 151.Xeomin 100 units powder for solution for injection. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6202/smpc

- 152.Dysport 300 units Powder for solution for injection. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/964/smpc

- 153.Herd CP, Tomlinson CL, Rick C, et al. Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of botulinum toxin for the prevention of migraine. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e027953. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027953

- 154.Aurora SK, Gawel M, Brandes JL, Pokta S, VanDenburgh AM. Botulinum Toxin Type A Prophylactic Treatment of Episodic Migraine: A Randomized, Double‐Blind, Placebo‐Controlled Exploratory Study. Headache. 2006;47(4):486-499. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00624.x

- 155.Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for Treatment of Chronic Migraine: Pooled Results From the Double‐Blind, Randomized, Placebo‐Controlled Phases of the PREEMPT Clinical Program. Headache. 2010;50(6):921-936. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01678.x

- 156.Krel R, Mathew PG. Procedural Treatments for Headache Disorders. Practical Neurology. May 2019. Accessed October 2024. https://practicalneurology.com/articles/2019-may/procedural-treatments-for-headache-disorders

- 157.Pellesi L. Combining onabotulinumtoxin A with a CGRP antagonist for chronic migraine prophylaxis: where do we stand? Front Pain Res. 2023;4. doi:10.3389/fpain.2023.1292994

- 158.Sacco S, Bendtsen L, Ashina M, et al. European headache federation guideline on the use of monoclonal antibodies acting on the calcitonin gene related peptide or its receptor for migraine prevention. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-018-0955-y

- 159.Sacco S, Amin FM, Ashina M, et al. European Headache Federation guideline on the use of monoclonal antibodies targeting the calcitonin gene related peptide pathway for migraine prevention – 2022 update. J Headache Pain. 2022;23(1). doi:10.1186/s10194-022-01431-x

- 160.Blumenfeld A, Ashkenazi A, Napchan U, et al. Expert Consensus Recommendations for the Performance of Peripheral Nerve Blocks for Headaches – A Narrative Review. Headache. 2013;53(3):437-446. doi:10.1111/head.12053