Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Recognise the signs and symptoms of Tourette syndrome;

- Understand the commonly used treatments for tics and Tourette syndrome;

- Support the monitoring of treatments used for the management of Tourette syndrome;

- Offer self-help support to individuals suffering from tics and Tourette syndrome.

Tourette syndrome is a complex heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disorder that presents before the age of 18 years and is characterised by motor and vocal tics1,2. The tic presents as a sudden, rapid, recurrent, non-rhythmic motor movement or vocalisation that often occurs as a response to an urge2. This urge resolves once the tic has occurred3.

Severity can range from mild transient tics to more impairing, debilitating symptoms, which can include behavioural issues and self-injurious behaviours1,2. The condition often causes physical health conditions and social interaction difficulties, leading to an overall poor quality of life. Tourette syndrome is the most complex presentation of the tic disorder spectrum2.

Prevalence

The actual prevalence of Tourette syndrome is unclear owing to strict diagnostic criteria, diverse diagnostic tools/systems, and lack of awareness by caregivers and healthcare professionals leading to poor identification and consequently delayed management4. Tourette syndrome has been reported as being prevalent in 0.2–0.3% of children aged 6–17 years1, and around 0.05% of adults5. It is thought to be around three times more prevalent in males than in females, with males having a more severe presentation than females4. It is twice as prevalent in adolescents aged 12–17 years than in younger age groups1.

Individuals with Tourette syndrome often have another neurodevelopmental or mental health diagnosis, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; 80%), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD; 70%) or autism spectrum disorder (ASD; 5–15%)1,2,4,6. Individuals with Tourette syndrome are also more likely to suffer from depression, anxiety and poor quality of life7.

Tics associated with Tourette syndrome usually present in childhood at the age of 3–8 years, with severity peaking at 8–12 years4. People with Tourette syndrome often go into complete remission after the age of 16 years; however, around 60% will continue to experience mild to moderate tics1,4.

Aetiology and pathophysiology

The primary cause of Tourette syndrome is not clear; however, it is thought to have a similar genetic profile to tic disorders with a very high heritability rate4. Tics are thought to be characterised by disinhibition of synaptic transmission in the cortico-striatal-thalamic-cortical system, owing to non-maturation of the connectivity. The serotonergic and dopaminergic pathway also may play a role in the pathogenesis8.

Signs, symptoms and associated factors

Family history, the presence of comorbidities, psychosocial stress and ability to identify the symptoms earlier on in childhood can partially predict the severity of the disorder into early adulthood4.

Tourette syndrome is associated with several factors and characteristics:

- Early onset of symptoms at the age of 3–8 years (usually intermittent in nature with varying intensity);

- An urge or need to perform abnormal movements that are often rapid, non-rhythmic and repetitive (e.g. shoulder shrugging, eye blinking, facial grimacing);

- An urge to perform repetitive vocal sounds (e.g. throat clearing, coughing, sniffing);

- Male gender;

- History or family history of Tourette syndrome, OCD or ADHD;

- Normal neurological examination (cranial nerves, muscle strength, sensory modalities, gait, coordination and mental status);

- Improvement in symptoms when focused on other tasks;

- Worsening of symptoms under stress;

- A premonitory urge before tics — an uncomfortable feeling of increased tension prior to the tic;

- An urge to perform other repetitive movements (e.g. touching, arranging, checking) to achieve a feeling of ‘just right’ or sense of completion.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Tourette syndrome can be difficult, especially when it co-exists with other neurodevelopmental or behavioural disorders. Diagnosis is often delayed for up to a decade after symptom onset. Based on self-reported symptoms, it is estimated that up to 73% of patients are misdiagnosed1,4. Assessment is less complicated when validated tools are used1.

Tourette syndrome is generally diagnosed by neurologists, psychiatrists, paediatricians and psychologists9. GPs and charities such as Tourette Scotland and Tourettes Action can help by signposting patients to both NHS and private clinicians that specialise in the diagnosis and treatment of Tourette syndrome6,10.

Diagnosis is made through a comprehensive clinical history from close family members or caregivers. Assessment should include: information on the onset of symptoms, duration and progression; nature of tics (urges and sensations associated with tics); what improves and exacerbates symptoms; family history; and coexisting conditions. Ideally, a medical or neurological examination is required. Patients with Tourette disorder should be assessed and managed by a multidisciplinary team11.

There are limited screening tools for the diagnosis of tic disorders, which causes delays in identification and timely management. Some of the more commonly used tic severity assessment tools are:

- The Motor or Vocal Inventory of Tics (MOVeIT) symptom screener12;

- The Description of Tic Symptoms (DoTS) brief diagnostic tool5;

- The Yale Global Tic Severity Score (YGTSS)13.

The YGTSS tool is the most widely used and has been regarded as the gold-standard outcome measure in assessing both the severity and impairment of tic disorder14,15. The MOVeIT and DoTS tools have been found to be useful in the identification of tic disorders in the general population of children6.

Tics

Tics are “abnormal involuntary movements and sounds that are discrete, repetitive, and have a waxing and waning course”5. Tics are generally classified as simple or complex, can be a combination of movements and/or vocal symptoms, and can vary in type, severity, frequency and complexity (see Table 1)4.

Tourette Scotland‘s website includes resources on the understanding tics and Tourette syndrome. It also has a more comprehensive checklist of the symptoms associated with the different types of tics16.

The severity and intensity of tics worsens under stress, fatigue or excitement, and improves when engaged in mental or physical activity or when there is a focus of attention4.

Disorders on the more severe end of the spectrum can present with significant behavioural and psychiatric symptoms, such as oppositional defiant behaviour, anxiety, depressive symptoms, disabling tics/compulsions and, in extreme cases, self-injurious behaviours.

Malignant Tourette syndrome is a more intense and disabling presentation of Tourette syndrome that can result in medical emergencies; for example, when severe motor or vocal tics cause physical damage. Malignant Tourette syndrome requires prompt intervention with treatments such as intensive behavioural therapy, pharmacological therapy and deep-brain stimulation17.

Criteria for diagnosing Tourette syndrome

Within the UK, the most widely used diagnostic criteria for the tic disorder are the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and the Tourette Syndrome Classification Study Group Criteria (see Table 2)2,18.

Differential diagnosis

When assessing for Tourette syndrome, it is important to rule out other conditions. Alternative diagnoses include neurological conditions (e.g. neurological lesions), seizure activity, akathisia, allergic rhinitis, conjunctivitis, compulsions and obsessions, premontory tic disorder, myoclonus, stereotypes, provisional tic disorder, Wilson’s disease, Sydenham’s chorea, paediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome, and paediatric auto-immune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcus2.

Functional tic-like behaviour (FTLB) resembles Tourette syndrome; however, their aetiologies differ. FTLB is often associated with anxiety, female sex, lack of familial history of tics, lack of premonitory urge and suppressability. It is important to distinguish between FTLBs and primary tics as they have different treatment pathways. Although tics can be treated with alpha-2-agonists and newer-generation antipsychotics, FTLBs is managed by treating the underlying comorbid trigger (such as anxiety)9.

Management

The prompt and accurate identification and diagnosis of Tourette syndrome enables individuals and their carers to seek early management and prevent the emergence of comorbid mental health conditions19. The goal of treatment is to improve quality of life. This often requires support from the multidisciplinary team, using different approaches.

The first-line treatment for Tourette syndrome is behavioural therapy: comprehensive behavioural intervention for tics (CBIT) or habit reversal therapy (HRT). There is strong evidence for the efficacy of HRT, either in isolation or as a component of CBIT for the management of tics in patients with Tourette syndrome20.

Pharmacists can support individuals with Tourette syndrome through early identification and educating the general public on how to reduce or manage symptoms with non-pharmacological methods. They can also help by signposting to Tourette charities that can offer more specialist and tailored support; for instance, Tourette Scotland and Tourette Action6,10.

Box 1: Practical tips for pharmacists

- Educate family and caregivers about the disorder and how they can best offer support;

- Encourage patients and their caregivers to minimise risk factors that aggravate symptoms;

- Encourage patients to implement lifestyles and behaviours, such as structured and targeted exercise and good sleep hygiene, which alleviate symptoms and reduce the associated stigma and distress;

- Effective management of comorbid conditions will reduce their impact on Tourette symptoms.

Pharmacological management

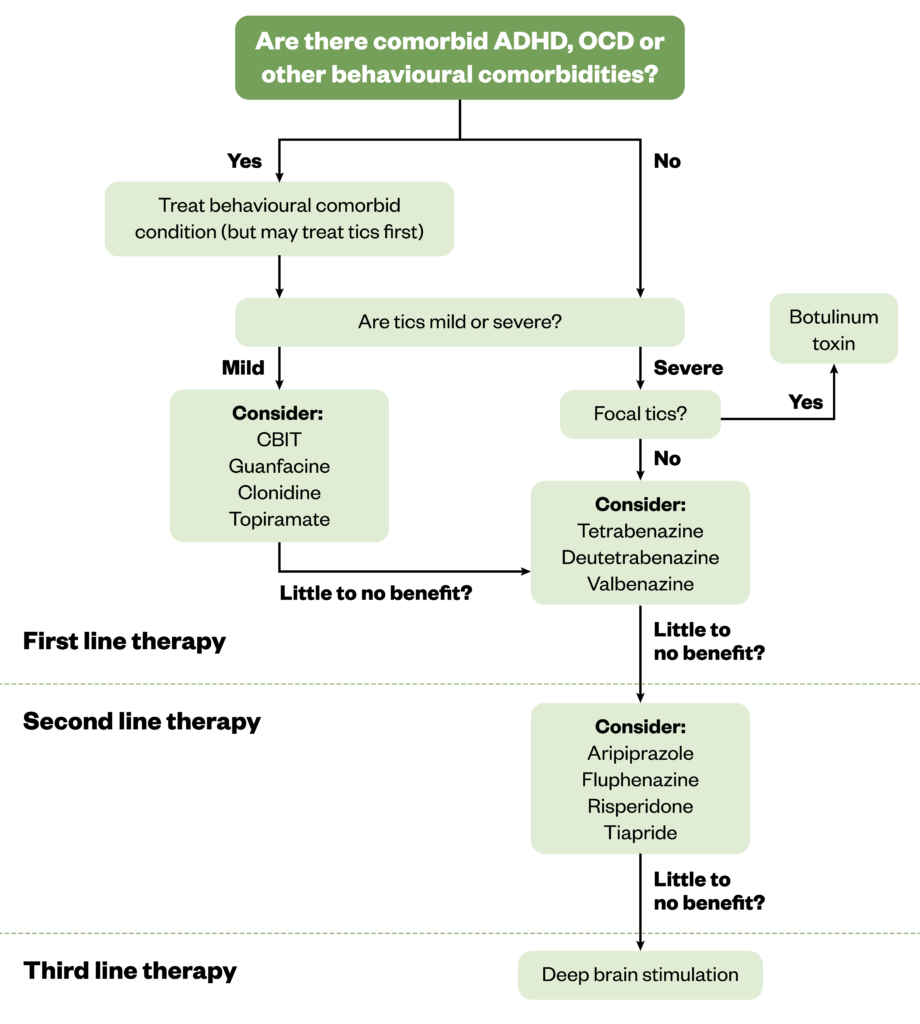

Pharmacological treatment is only indicated when symptoms are causing significant distress or functional impairment and should be considered when behavioural intervention has not been effective21. Treatment is often complicated because of the fluctuating severity of symptoms over time, other co-existing conditions and the lack of licensed or evidence-based treatments1. A suggested treatment algorithm is shown in Figure 1.

Choice of pharmacological treatment should be made following consideration of each individual patient’s needs. Some of the factors to be considered include patient symptoms, tolerability, preference, clinician’s experience of management and comorbid conditions3,22–25. The guiding principle is to use monotherapy at the lowest effective dose, tailoring treatment to each patient’s needs. When the use of a single agent has been unsuccessful in suppressing tics or there is intolerance to treatment, combination treatment using agents with varying modes of action could be useful1.

The first-line choice for the treatment of Tourette syndrome depends on its severity. For mild Tourette syndrome, CBIT is recommended. Alpha-2-agonists, such as clonidine and guanfacine, are often considered as first-line pharmacological treatments for suppression of tics associated with Tourette syndrome. Newer-generation antipsychotics, such as aripiprazole and risperidone, are second-line agents. Aripiprazole and clonidine have demonstrated the most efficacy in the management of tics and Tourette syndrome3.

For resistant focal severe tics, botulinum toxin A is often used. Aripiprazole, risperidone, benzamides, cannabinoids and fluphenazine are used as second-line treatments. More invasive treatments, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and deep brain stimulation, are considered as third-line treatments26. Other alternative agents include antiepileptics, VMAT2 inhibitors, benzodiazepines and botulinum toxin A1.

Table 3 lists the various pharmacological treatment options and when they should be used.

Treatment of Tourette syndrome with comorbid conditions

Tourette syndrome often co-exists with other neurodevelopmental disorders: ADHD, autism spectrum disorder and OCD are the most common comorbid conditions. The strong association between these comorbid disorders and Tourette syndrome, along with the presence of multiple loci in the brain that may underlie biological mechanisms, has led to the assumption that they all lie on the impulsivity–compulsivity continuum27.

It is recommended that individuals with Tourette syndrome should be monitored periodically, especially at the age of 6–15 years, when the tics are usually at their worst1,2. Treatment should focus on the most impairing or disabling comorbidities28.

Table 4 shows the treatment algorithm for Tourette syndrome with or without ADHD or OCD2.

Complications associated with pharmacological treatments

Some pharmacological treatments can cause complications (see Table 5).

Novel treatments

There are some emerging treatments in the management of Tourette syndrome, such as cannabinoids, deutratrabenazine, transcranial magnetic stimulation and deep brain stimulation29–31. Digitally-enabled therapy for chronic tic disorders and Tourette syndrome has recently been recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence for the management of chronic tic and Tourette syndrome32.

Training

Pharmacists and pharmacy staff can access free training on Tourette syndrome through charity organisations. Tourettes Action have online eLearning modules on understanding Tourette syndrome. There is also training available on the NHS learning hub10.

Conclusion

Tourette syndrome is often poorly managed owing to a lack of awareness of the disorder and underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis. The highest prevalence and worst severity of Tourette syndrome is in adolescence. Choice of therapy (non-pharmacological and pharmacological) should be individualised to the patient based on the severity of symptoms, comorbid conditions, lifestyle, tolerability and response to treatment. Pharmacists play a major role in early identification, signposting to appropriate services for management and offering simple measures to help manage tics associated with Tourette syndrome. Specialist pharmacists can also support the optimisation of treatments, monitor for side effects and help manage complications associated with pharmacological treatment.

- This article was amended on 11 July 2025 to remove a link to a source of additional information due to user access restrictions

- 1.Seideman MF, Seideman TA. A Review of the Current Treatment of Tourette Syndrome. The Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2020;25(5):401-412. doi:10.5863/1551-6776-25.5.401

- 2.Best Practice: Tourette’s Syndrome. British Medical Journal . January 2023. Accessed July 2025. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/1042

- 3.Besag FM, Vasey MJ, Lao KS, Chowdhury U, Stern JS. Pharmacological treatment for Tourette syndrome in children and adults: What is the quality of the evidence? A systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2021;35(9):1037-1061. doi:10.1177/02698811211032445

- 4.Johnson KA, Worbe Y, Foote KD, Butson CR, Gunduz A, Okun MS. Tourette syndrome: clinical features, pathophysiology, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology. 2023;22(2):147-158. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(22)00303-9

- 5.Adams HR, Augustine EF, Bonifacio K, et al. Evaluation of New Instruments for Screening and Diagnosis of Tics and Tic Disorders in a Well-Characterized Sample of Youth with Tics and Recruited Controls. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2023;9(2):216-230. doi:10.1080/23794925.2023.2178040

- 6.Annual report 2023. Tourette Scotland. Accessed July 2025. https://www.tourettescotland.org/_files/ugd/fb841a_ca22046f44d54a99a3a069d329485edd.pdf

- 7.Billnitzer A, Jankovic J. Current Management of Tics and Tourette Syndrome: Behavioral, Pharmacologic, and Surgical Treatments. Neurotherapeutics. 2020;17(4):1681-1693. doi:10.1007/s13311-020-00914-6

- 8.Nomura Y. Pharmacological therapy for Tourette syndrome: What medicine can do and cannot do. Biomedical Journal. 2022;45(2):229-239. doi:10.1016/j.bj.2021.09.002

- 9.Pringsheim T, Ganos C, Nilles C, et al. European Society for the Study of Tourette Syndrome 2022 criteria for clinical diagnosis of functional tic‐like behaviours: International consensus from experts in tic disorders. Euro J of Neurology. 2023;30(4):902-910. doi:10.1111/ene.15672

- 10.Tourettes Action. Tourettes Action. Accessed 2025. www.tourettes-action.org.uk

- 11.Gadoth N. An Updated Overview of The Complex Clinical Spectrum of Tourette Syndrome. CDTH. 2020;15(2):86-91. doi:10.2174/1574885514666191120143747

- 12.Lewin AB, Brennan E, Small B, Bolton C, Dickinson S, Murphy TK. Development of a Tic Screener: The Motor or Vocal Inventory of Tics (MOVeIT-14). Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2024;9(2):205-215. doi:10.1080/23794925.2024.2324769

- 13.Yale Global Tic Severity Scale. Yale Child Study Centre. 2018. Accessed July 2025. https://pandasnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/YGTSS.pdf

- 14.Jimenez-Shahed J. Medical and Surgical Treatments of Tourette Syndrome. Neurologic Clinics. 2020;38(2):349-366. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2020.01.006

- 15.Ramsey KA, McGuire JF. Advancements in the phenomenology, assessment, and treatment of Tourette syndrome. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2023;37(2):57-64. doi:10.1097/yco.0000000000000922

- 16.Checklist of tics and symptoms. Tourette Scotland . 2021. Accessed July 2025. https://www.tourettescotland.org/_files/ugd/fb841a_b9132c1b539443c99058999a4b7a9c80.pdf

- 17.Baizabal-Carvallo JF, Cavanna AE, Jankovic J. Tics emergencies and malignant tourette syndrome: Assessment and management. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2024;159:105609. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2024.105609

- 18.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR). 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Accessed July 2025. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm

- 19.Hirschtritt ME, Lee PC, Pauls DL, et al. Lifetime Prevalence, Age of Risk, and Genetic Relationships of Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders in Tourette Syndrome. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):325. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2650

- 20.Cavanna AE, Manglani R. Efficacy of habit reversal training for the treatment of tics in patients with Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. J Psychopathol Clin Sci . 2025;31(1). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/389206797_Efficacy_of_habit_reversal_training_for_the_treatment_of_tics_in_patients_with_Tourette_syndrome_and_other_tic_disorders_SUMMARY

- 21.Lenka A, Jankovic J. An update on the pharmacological management of Tourette syndrome and emerging treatment paradigms. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2024;24(10):1025-1033. doi:10.1080/14737175.2024.2382463

- 22.Frey J, Malaty IA. Tourette Syndrome Treatment Updates: a Review and Discussion of the Current and Upcoming Literature. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2022;22(2):123-142. doi:10.1007/s11910-022-01177-8

- 23.Can A, Vermilion J, Mink JW, Morrison P. Pharmacological Treatment of Tourette Disorder in Children. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2024;34(8):346-352. doi:10.1089/cap.2023.0026

- 24.Cavanna AE. Current and emerging pharmacotherapeutic strategies for Tourette syndrome. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2022;23(13):1523-1533. doi:10.1080/14656566.2022.2107902

- 25.Roessner V, Eichele H, Stern JS, et al. European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders—version 2.0. Part III: pharmacological treatment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;31(3):425-441. doi:10.1007/s00787-021-01899-z

- 26.Gong H, Du X, Su A, Du Y. Pharmacological treatment of Tourette’s syndrome: from the past to the future. Neurol Sci. 2023;45(3):941-962. doi:10.1007/s10072-023-07172-2

- 27.Yang Z, Wu H, Lee PH, et al. Investigating Shared Genetic Basis Across Tourette Syndrome and Comorbid Neurodevelopmental Disorders Along the Impulsivity-Compulsivity Spectrum. Biological Psychiatry. 2021;90(5):317-327. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.12.028

- 28.Manbeck C, Johnson T, Sharp G. A narrative review to guide treatment and care for children with Tourette syndrome. Brain Disorders. 2023;11:100088. doi:10.1016/j.dscb.2023.100088

- 29.Dyke K, Jackson G, Jackson S. Non-invasive brain stimulation as therapy: systematic review and recommendations with a focus on the treatment of Tourette syndrome. Exp Brain Res. 2021;240(2):341-363. doi:10.1007/s00221-021-06229-y

- 30.Liang B, Zhou Y, Jiang C, Zhao T, Qin D, Gao F. Role and related mechanisms of non-invasive brain stimulation in the treatment of Tourette syndrome. Brain Research Bulletin. 2025;222:111258. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2025.111258

- 31.Müller-Vahl KR, Szejko N, Verdellen C, et al. European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders: summary statement. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;31(3):377-382. doi:10.1007/s00787-021-01832-4

- 32.Digital therapy for chronic tic disorders and Tourette syndrome: early value assessment’ NICE Health Technology Evaluation (HTE25). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2025. Accessed July 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/hte25