Shutterstock.com

After reading this learning article, you should be able to:

- Understand the causes and risk factors precipitating the development of pre-eclampsia;

- Understand the diagnostic process and when to refer;

- Manage patients with pre-eclampsia in line with current guidance, including women with severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, and in the postpartum period.

Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy are common, affecting 10–15% of women[1]. Pre-eclampsia, a condition characterised by new-onset hypertension and proteinuria, complicates around 3–5% of pregnancies (10% of women who have not previously given birth). Globally, up to 1% of women will go on to develop eclampsia (life-threatening emergency characterised by seizures), although the incidence in the UK and Europe is 0.03%[1].

Unlike chronic hypertension, which predates pregnancy or is recognised prior to 20 weeks gestation, pre-eclampsia presents after this period as either a complication of new onset, or gestational, hypertension; although initial pathological changes may begin in early pregnancy. Around 15% of women presenting with gestational hypertension are likely to progress to pre-eclampsia, which may occur up to six weeks after delivery[1]. Patients with pre-existing or chronic hypertension prior to 20 weeks have a 25% risk of developing superimposed pre-eclampsia[1]. Despite a significant reduction in mortality over the past 30 years, pre-eclampsia remains a leading cause of maternal death[2].

Early identification during the antenatal period is crucial to minimise maternal complications, and reduce foetal morbidity and mortality from prematurity and intrauterine growth restriction.

Causes and symptoms

Pre-eclampsia is primarily considered a placental disorder, where failure of the uterine spiral arteries to remodel themselves during pregnancy (a consequence of abnormal trophoblast invasion) results in reduced utero-placental perfusion and subsequent foetal hypoxia[1,3]. The oxidative stress caused by under-perfusion leads to the release of circulating factors (placental syncytial fragments), which induce a maternal inflammatory response that subsequently causes endothelial cell dysfunction, triggering widespread vasoconstriction and capillary leakage. This results in the multisystem disorder evident in pre-eclampsia[3]. Late-onset pre-eclampsia beyond 34 weeks gestation may be attributable to normal maternal perfusion failing to meet the metabolic demands of the placenta and foetus, coupled with an increased maternal susceptibility and immune response to the circulating factors[3,4].

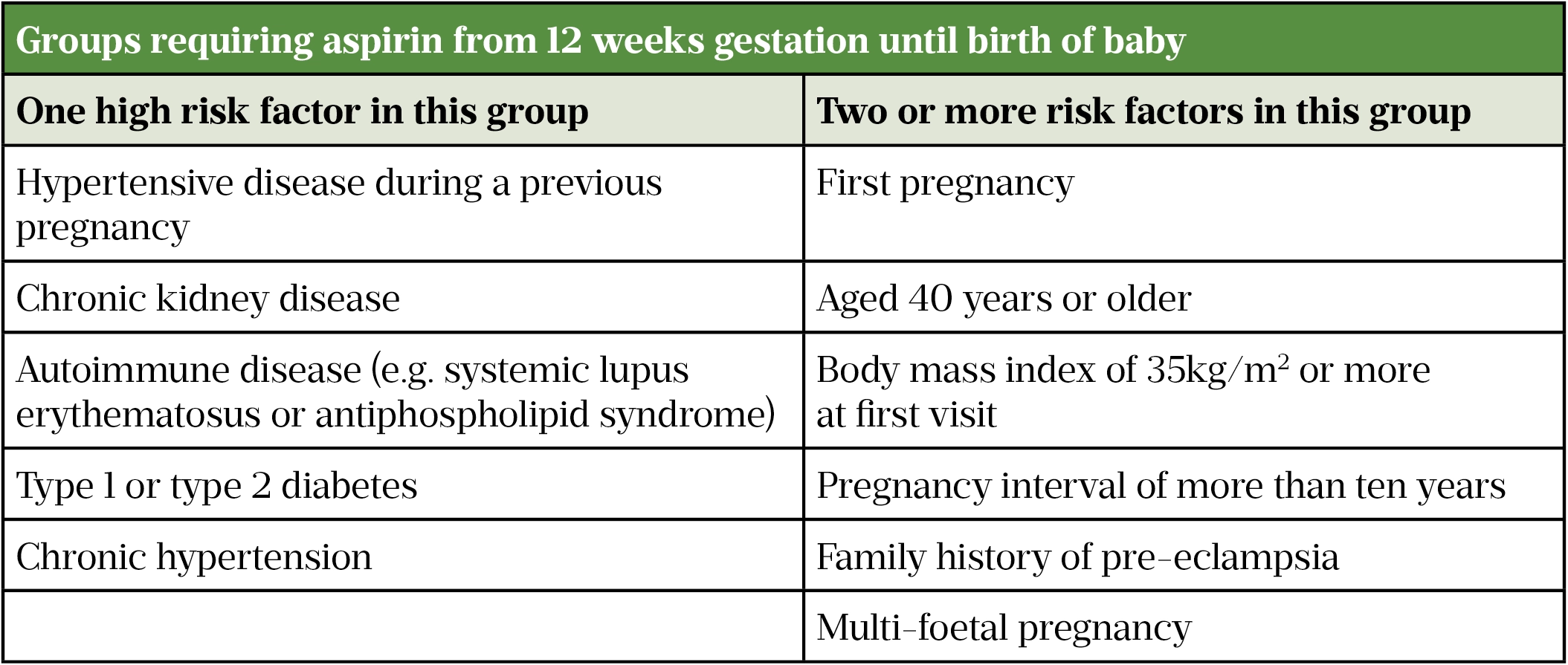

Multiple factors may put women at higher risk of developing pre-eclampsia (see Table 1); these should be determined early on in pregnancy at the initial antenatal appointment with a midwife.

Table 1: Groups requiring aspirin from 12 weeks gestation until birth of baby

As new-onset proteinuria may accompany high blood pressure (BP; defined as a systolic BP ≥140mmHg and/or diastolic ≥90mmHg), urinary protein and BP should be checked at each antenatal visit. In the early stages, the mother may remain asymptomatic, but absence of these signs does not exclude a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia as they may present later. As pre-eclampsia is a a multisystem disorder, healthcare professionals should be alert to other investigations as multiple factors may be indicative of the condition, confounding differential diagnosis. Any abnormalities identified during routine antenatal screening check-up should be followed up with regular monitoring, including close to delivery and postpartum (see Box 1).

Box 1: Investigations possibly suggestive of pre-eclampsia

- Protein creatinine ratio ≥30mg/mmol; albumin creatinine ratio ≥8mg/mmol;

- Thrombocytopenia (platelet count rapidly falling or absolute level <100 x 109/L);

- Prolonged clotting times;

- Raised serum creatinine ( ≥90micromol/L or ≥1mg/100ml);

- Increased haematocrit and haemoglobin levels (above normal pregnancy levels);

- Anaemia if haemolysis; associated with raised lactate dehydrogenase and bilirubin;

- Abnormal liver function tests, particularly raised transaminases (alanine transaminase ≥70IU/L or twice upper limit of normal range — NB: alkaline phosphatase normally raised in pregnancy);

- Reduced foetal growth, oligohydramnios (reduced amniotic fluid);

- Abnormal uterine artery Doppler (bilateral notches and increased resistance/pulsatility index at 22–24 weeks gestation predict pre-eclampsia);

- Abnormal umbilical artery Doppler (reduced, absent or reversed end diastolic flow indicating foetal compromise);

- Low placental growth factor (PlGF; reduced in pre-eclampsia and predictive of delivery for pre-eclampsia within two weeks — NB: reference ranges vary between different PlGF tests).

Source: Handbook of Obstetric Medicine[1]

The presence of any of the following symptoms requires immediate investigation:

- Severe headache;

- Problems with vision (e.g. blurring or flashing lights);

- Abdominal pain just below the ribs;

- Vomiting;

- Sudden swelling of the face, hands or feet[5].

Pharmacists should refer patients presenting with any of these symptoms for urgent review by their GP, maternity assessment unit or emergency department.

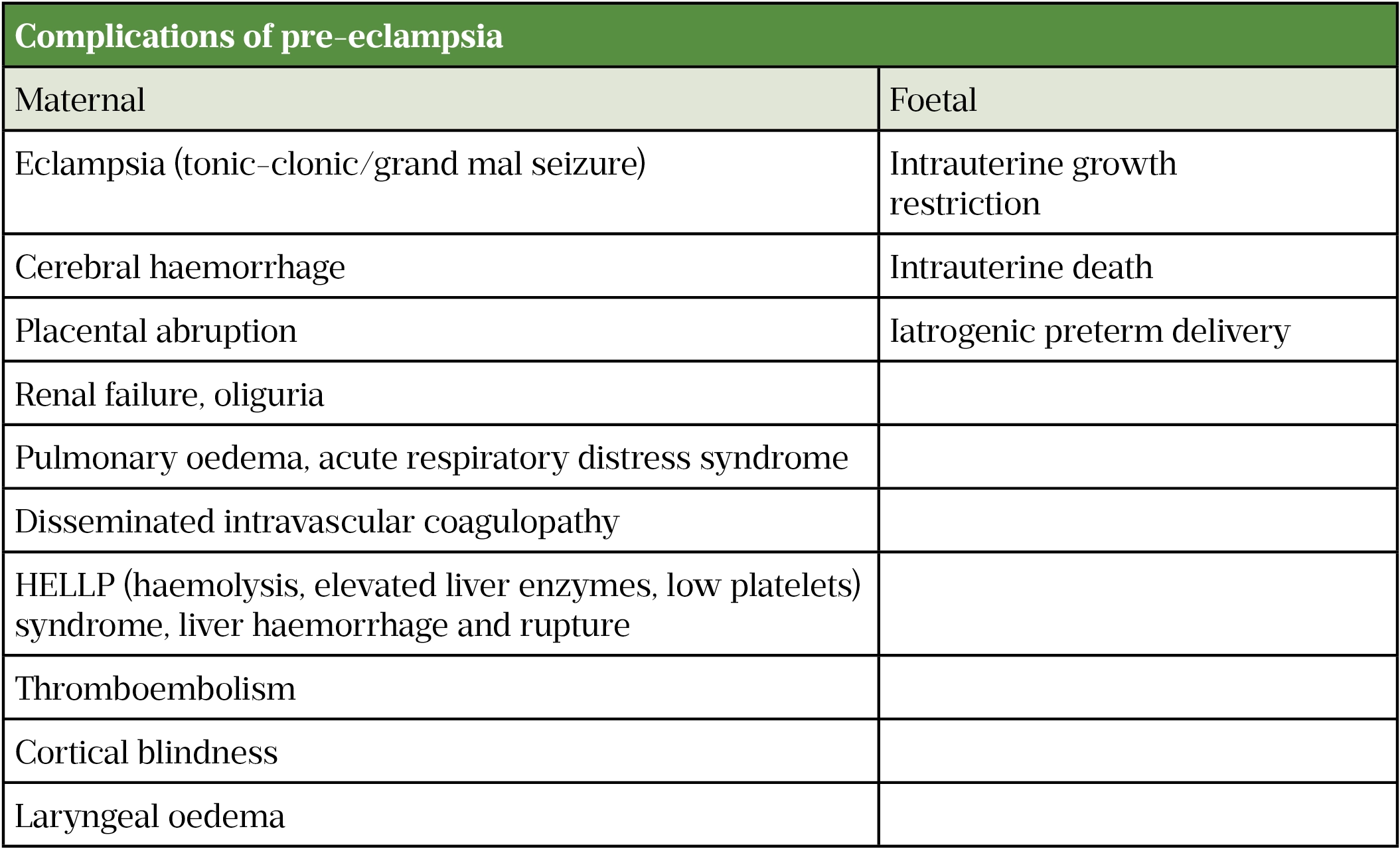

Failure to manage symptoms early increases the likelihood of complications (see Table 2). Risk prediction models, such as fullPIERS and PREP-S, may be used to determine the risk of life-threatening complications and guide decision making about appropriate care[5].

Table 2: Complications of pre-eclampsia

Pharmacists in primary care should routinely provide general diet and lifestyle advice to pregnant women, including appropriate weight management, regular exercise, healthy eating, salt reduction and smoking cessation[5]. Promoting folic acid for women considering pregnancy (400 micrograms per day up to 12 weeks gestation), and vitamin D (10 micrograms per day) during pregnancy and breastfeeding, together with appropriate inactivated vaccinations (e.g. seasonal flu, whooping cough) also help to ensure healthy mothers and babies[6,7].

Diagnosis

Pre-eclampsia and its clinical features vary in severity, timing, progression and order of onset. Assessment and diagnosis must therefore be made by a specialist healthcare professional in secondary care.

A diagnosis of hypertension is made when there is a single diastolic BP of 110mmHg or two consecutive readings of 90mmHg at least four hours apart[6]. A systolic BP ≥160mmHg on two consecutive readings at least four hours apart would warrant immediate treatment and monitoring every 15–30 minutes until BP falls below 160/110mmHg[5,6]. BP monitoring should continue once or twice per week until BP is 135/85mmHg or less[5]. During labour, all women with hypertension should have their BP checked hourly and every 15-30 minutes if above 160/110mmHg[5].

Urine should be tested for the presence of protein, using an automated reagent-strip reading device for dipstick screening, avoiding the first morning void (higher chance of false positives)[5]. Following a positive screen, albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR) or protein:creatinine ratio (PCR) should be used to quantify degree of proteinuria. An ACR ≥8mg/mmol or PCR ≥30mg/mmol may be suggestive of pre-eclampsia if accompanied by other signs and symptoms. A 24-hour urine collection to quantify proteinuria is not routinely recommended[5]. Ongoing urinalysis for protein is not required, unless there is uncertainty or new symptoms present, but regular BP monitoring should be increased to at least every 48 hours and more frequently if the woman is admitted[5]. Self-monitoring with a pregnancy-validated BP monitor — introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic in place of face-to-face consultations — may be an acceptable option for some women[8].

If pre-eclampsia is suspected, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends considering single placental growth factor (PlGF) testing between 20–36 weeks and 6 days of pregnancy, using one of the four recommended testing kits (refer to manufacturer’s guidance as not all tests are indicated for the totality of this period)[9]. Certain high-risk groups, such as people from African, Caribbean and Asian family backgrounds, may particularly benefit from testing. In normal pregnancy, PlGF levels rise and peak at 26–30 weeks; however, in pre-eclampsia, levels may be unusually low. Low levels may suggest placental disease, but do not solely confirm the presence of pre-eclampsia. The decision to offer a planned early birth to those with preterm pre-eclampsia should not be made on PlGF test results alone; consideration should be given to other clinical symptoms indicating risk to mother and baby, and other tests including full blood count, liver function and renal function tests performed[5,9]. In particular, care should be taken if testing in multiple pregnancy as accuracy of results is not guaranteed[9].

Foetal growth should be monitored in each woman with hypertension, including ultrasound and/or umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry, and cardiotocography if clinically indicated. These should be repeated every two weeks in women with pre-eclampsia or severe gestational hypertension[5].

Management

The only definitive cure for pre-eclampsia is delivery of the baby and placenta. When and how this takes place is determined on an individual basis, considering the health of both the mother and the foetus. Antenatal screening and regular maternal and foetal monitoring is therefore essential. Women with mild hypertension, with or without pre-eclampsia, may be managed in the community, especially if they are able to monitor BP themselves. Admission is only required if there are concerns for the mother or baby and regular surveillance becomes necessary. Prolonging pregnancy in pre-eclampsia should be for the benefit of the foetus alone; however, on average, most women with pre-eclampsia require delivery within two weeks of diagnosis[1]. Beyond 37 weeks gestation, delivery is generally recommended within 24–48 hours and further prolongation does not appear to have significant advantage[1,5].

Aspirin

Women deemed as high risk (see Table 1) should be started on aspirin 75–150mg daily from 12 weeks until birth[5].

Aspirin inhibits platelet cyclooxygenase and, therefore, thromboxane A2 (TXA2) synthesis. TXA2 is a potent vasoconstrictor and hypertensive agent produced by endothelial cells; production is increased during pre-eclampsia[1]. Doses of aspirin at 150mg have been found to be effective in reducing risk of early onset pre-eclampsia (<37 weeks gestation) but whether this dose is more effective than 75mg remains unclear[1]. Limited evidence also suggests that best results are seen if the dose is taken in the evening, preferably at night[10].

Pharmacists can facilitate timely supply of aspirin — low-dose aspirin is available over the counter — however, licensing precludes its sale to pregnant women. Women with pre-eclampsia are therefore required to obtain prescriptions, usually from their GP, as they may not see an obstetrician before 12 weeks gestation. Midwives could supply aspirin and would benefit from secondary care pharmacists facilitating this service by supporting the development of patient group directions (PGDs) and obtaining aspirin prepacks; MBRRACE-UK have advocated for a national PGD and there is one available on the specialist pharmacy service (SPS) website[11].

Antihypertensives

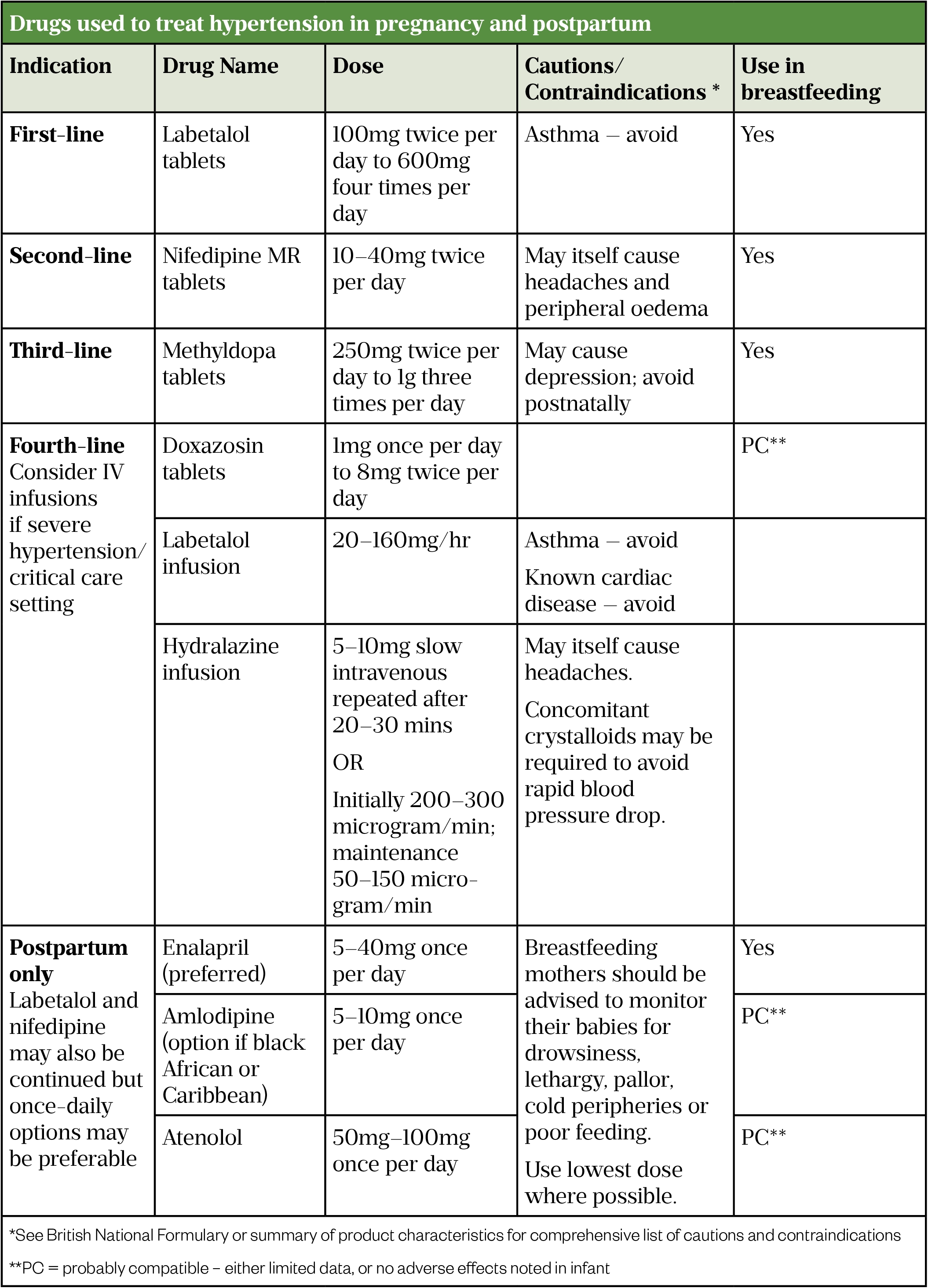

Women with BP consistently above 140/90mmgHg should be offered pharmacological treatment, with the aim of reducing BP to ≤135/85mmHg[5]. BP ≥160/110mmHg requires mandatory treatment. Labetalol and nifedipine are the preferred antihypertensives in pregnancy, followed by methyldopa (see Table 3 for treatment options)[5]. Labetalol is the only antihypertensive licensed for use in pregnancy but the other recommended options have been used extensively without foetal adverse effects.

Table 3: Drugs used to treat hypertension in pregnancy and postpartum

Diuretics, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) should be avoided during pregnancy: the former depletes an already reduced intravascular volume commonly seen in pre-eclampsia, while the latter two groups can cause foetal harm[1]. Women with chronic hypertension treated with these medicines prior to pregnancy should be switched to first- or second-line options; ideally pre-pregnancy discussion and planning should take place[5].

Treatment often needs to continue post-delivery and BP monitored regularly until within normal range; home monitoring is therefore useful. Women should be discharged with a clear care plan and follow-up should take place with a GP or specialist at two weeks (if being treated) and again at six to eight weeks (all patients who had pre-eclampsia)[5].

Pharmacists should provide information and reassure women concerned about taking antihypertensive medication during their pregnancy and while breastfeeding (see Box 2). Pre-pregnancy counselling is essential for those women with chronic hypertension or renal conditions treated with ACEis, ARBs or diuretics; these women should be advised to speak to their GP or specialist about safer alternative medicines if pregnancy is being planned or is confirmed[5].

Box 2: Medication in pregnancy and breastfeeding information resources

- UK Teratology Information Service

- Best Use of Medicines in Pregnancy

- UK Drugs in Lactation Advisory Service

- Drugs and Lactation database

- Hale TW. Medications & Mother’s Milk. Springer Publishing Company: New York; 2021

NB: Information in the British National Formulary/Summary of Product Characteristics is often inadequate if used as a sole reference source.

Severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Severe hypertension unresponsive to treatment or associated with ongoing symptoms, progressive deterioration in organ function or failure of foetal growth are all indicative of worsening pre-eclampsia. Escalation to critical care may be required and consideration given to early delivery. Any decision around delivery should involve a senior obstetrician and the following treatments should be initiated:

- Escalation of antihypertensives to intravenous management if uncontrolled by oral therapy;

- Fluid restriction to 80mL/hour unless there is fluid loss or if administering hydralazine injection;

- Parenteral magnesium sulphate injection given to reduce cerebral vasospasm and risk of eclamptic seizures (loading dose 4g followed by 1g/hour infusion for 24 hours or, in the event of seizures, for 24 hours after last seizure); standard anticonvulsant drugs such as diazepam or phenytoin should not be used. Intravenous magnesium sulphate is also given for foetal neuroprotection if delivery is likely to be before 34 weeks;

- A course of antenatal corticosteroids (betamethasone/dexamethasone) to support foetal lung maturation if an early birth is planned, prior to 36 weeks[5].

Postpartum

Although the placenta is removed post-delivery, symptoms may take several weeks to resolve completely, particularly in hypertension, which can often deteriorate within the first few days after birth. Ergometrine, indicated for postpartum haemorrhage, should be avoided immediately post-delivery as this may cause an acute rise in BP[1]. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should also be avoided as they may worsen acute kidney injury and aggravate fluid retention and pulmonary oedema[1]. Fluid restrictions should continue until the patient is drinking freely and normal urine output is confirmed[13].

Women who have had pre-eclampsia should be counselled on possible future risks, including the recurrence of pre-eclampsia in future pregnancies, an increased likelihood of developing hypertension, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in later life[5]. These women may benefit from ongoing monitoring for early identification of these conditions and community pharmacists may be well placed to provide such a service. Further information for women and healthcare professionals is available from Action on Pre-eclampsia and the Pre-eclampsia Foundation.

How to have effective consultations on contraception in pharmacy

What benefits do long-acting reversible contraceptives offer compared with other available methods?

Community pharmacists can use this summary of the available devices to address misconceptions & provide effective counselling.

Content supported by Bayer

This article has been reviewed by the expert authors to ensure it remains relevant and up to date, following its original publication in The Pharmaceutical Journal in April 2021.

- 1Nelson-Piercy C. Handbook of Obstetric Medicine. 6th ed. Abingdon, UK: : CRC Press 2020.

- 2Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care: Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2016-18. MBRRACE-UK, National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford 2022. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/maternal-report-2022/MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_MAIN_Report_2022_UPDATE.pdf (accessed Jun 2023).

- 3Samangaya R, Heazell A, Baker P. Hypertension in pregnancy. In: Greer I, Nelson-Piercy C, Walters B, eds. Maternal Medicine: Medical Problems in Pregnancy. Philadelphia, USA: : Elsevier Limited 2007. 40–52.

- 4Burton GJ, Redman CW, Roberts JM, et al. Pre-eclampsia: pathophysiology and clinical implications. BMJ 2019;:l2381. doi:10.1136/bmj.l2381

- 5Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline NG133. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133 (accessed Jun 2023).

- 6Antenatal care for uncomplicated pregnancies. Clinical guideline CG62. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019.https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG62 (accessed Jun 2023).

- 7Vaccinations in pregnancy. NHS. 2019.https://www.nhs.uk/pregnancy/keeping-well/vaccinations (accessed Jun 2023).

- 8Self-monitoring of blood pressure in pregnancy. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . 2020.https://www.rcog.org.uk/media/nkpfvim5/2020-12-09-guidance-for-maternal-medicine-services-in-the-coronavirus-c.pdf (accessed Jun 2023).

- 9PIGF-based testing to help diagnose suspected pre-eclampsia. Diagnostics guidance DG23. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2016.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg49 (accessed Jun 2023).

- 10Ayala DE, Ucieda R, Hermida RC. Chronotherapy With Low-Dose Aspirin for Prevention of Complications in Pregnancy. Chronobiology International 2012;30:260–79. doi:10.3109/07420528.2012.717455

- 11Supply of aspirin tablets for individuals at high risk of pre-eclampsia in location/service/organisation. Patient group direction. 2022.https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sps.nhs.uk%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2022%2F02%2FPMP-Aspirin-National-PGD-template-FINAL-Feb-2022-1.doc&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK (accessed Jun 2023).

- 12British National Formulary. 81st ed. London: : British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain 2021. www.medicinescomplete.com (accessed Jun 2023).

- 13Walker J, Morley L. Pre-eclampsia. BMJ Best Practice. 2020.https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/326 (accessed Jun 2023).