KATERYNA KON/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand what testicular cancer is, the different types, who can be affected and the risk factors;

- Recognise the symptoms of testicular cancer and know how it is diagnosed;

- Know the available treatment options and their associated side effects;

- Be aware of the support available for patients with testicular cancer.

Introduction

Testicular cancer is a cancer originating in one or both testicles in those with male reproductive organs. It is a relatively rare cancer, with around 2,400 new cases diagnosed in the UK each year, which is a 30% rise in cases since the 1990s1. It can affect anyone who has testicles, including men, transgender women and those assigned male at birth who have their testicles retained2.

More than 95% of testicular cancer cases arise from the germ cells, which are the cells that develop into sperm3. Germ cell testicular cancers may be further classified into two main types: seminomas and non-seminomas2. In some cases, the germ cell tumour may be a mixture of both3. More information about the types of testicular cancer can be found below.

While the disease is most prevalent in people aged 25–40 years, it can occur in individuals aged as young as 15 years. Risk factors include undescended testicles — which may occur at birth or during infancy — and family history2. When detected early, testicular cancer is usually treatable4. Given the importance of early diagnosis and the challenges surrounding men’s health awareness and reporting (e.g. negative perceptions around seeking help), it is crucial for all healthcare professionals — including pharmacists — to recognise the signs and symptoms of testicular cancer and know how to appropriately refer or signpost patients4.

This article will discuss what testicular cancer is, its affected populations, diagnostic procedures and treatment options.

Cancer learning ‘hub’

Pharmacists are playing an increasingly important role in supporting patients with cancer, working within multidisciplinary teams and improving outcomes.

However, in a rapidly evolving field with numbers of new cancer medicines is increasing and the potential for adverse effects, it is now more important than ever for pharmacists to have a solid understanding of the principles of cancer biology, its diagnosis and approaches to treatment and prevention.

This new collection of cancer content, brought to you in partnership with BeOne Medicines, provides access to educational resources that support professional development for improved patient

Risk factors

A primary risk factor for testicular cancer is cryptorchidism (undescended testicles), with a relative risk of malignancy of 3.7–7.5 times higher than those with descended testicles5. Other risk factors include family history of cancer, previous diagnosis of testicular cancer, testicular atrophy, gonadal dysgenesis and white ethnicity6. Rates of testicular cancer are five times higher in white men than in black men; the reasons for this are unclear7.

Other risk factors include: HIV (when the relative risk of seminoma is five-fold higher in men with HIV than in age-matched controls without HIV); occupational exposures to carcinogens, such as pesticides; inguinal hernias and genetic abnormalities6,8.

Symptoms

The most common symptom of testicular cancer is a lump or swelling in a testicle, which can vary in size and may be as a small as a pea1. While most testicular lumps are non-cancerous, it is crucial that all lumps are clinically investigated. Patients may also experience pain of varying severities, including a sharp pain or dull ache; however, more than 85% of testicular masses are painless1,9–11. Other sensations include a feeling of heaviness in the scrotum or, in some cases, a sudden collection of fluid in the scrotum. If the cancer has metastasised beyond the immediate area, patients may present with extra-testicular symptoms. Around 5–10% of patients will have extra-testicular symptoms, with or without apparent primary tumour in the testes. These include bone pain (indicating spread of the cancer to the bone [i.e. skeletal metastases)], lower extremity swelling (venous occlusion), supraclavicular lymph node enlargement, abdominal pain, symptoms and/or signs of hyperthyroidism (rare) and gynaecomastia3,9–11.

Testicular cancer is usually diagnosed as a unilateral testicular mass detected by the patient or via incidental finding. Only 1–2% of cases present with bilateral testicular mass2,3.

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis is crucial for testicular cancer: more than 95% of patients with early-stage disease are cured with appropriate therapy12–14. Therefore, it is important that patients presenting with the symptoms described above are encouraged to visit their GP immediately for initial assessment and onward referral as appropriate.

The GP will examine the patient and take a full history and refer those with symptoms of testicular cancer either for an urgent ultrasound or to the urology department at the patient’s local hospital for further initial investigation.

At the hospital, patients will undertake an initial assessment, as well as having several scans. The first-line test in patients with palpable scrotal abnormalities is an ultrasound with colour doppler of the testis, which will confirm a mass. Further scans, such as CT, MRI or PET, may include imaging of the chest, pelvis and abdomen. There are some blood tests that can also help with the diagnosis and the sub-type; these are called the tumour markers and include beta-HCG (human chorionic gonadotrophin), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)10,12,15.

A biopsy is generally not advised in the evaluation of a testicular mass; diagnosis is established by removing and examining the involved testicle. In highly selected patients, testis sparing surgery (TSS) through an inguinal incision may be offered as alternative to radical orchiectomy (removal of the testis/testicle) — additional information on TSS can be seen below6.

The investigations described above can help rule out other differential diagnoses. Other conditions that may present with scrotal pain or changes include:

- Testicular torsion (or torsion of spermatic cord);

- Epididymitis (inflammation of the epididymis [a narrow tube attached to the testicles that sperm travels through]);

- Appendix testis torsion (torsion of the appendix testes [a tiny piece of tissue attached to the upper part of the testes]);

- Appendix epididymis torsion (torsion of the appendage on top of the epididymis); or

- Epididymo-orchitis (inflammation of the epididymis, the tube that stores and transports sperm).

Other conditions that may present with a lump on the testicles could be a cyst (epididymal or intra-testicular benign) or a haematoma6. All patients presenting with these symptoms should be referred for a confirmed diagnosis and appropriate management by a specialist6.

Histopathology

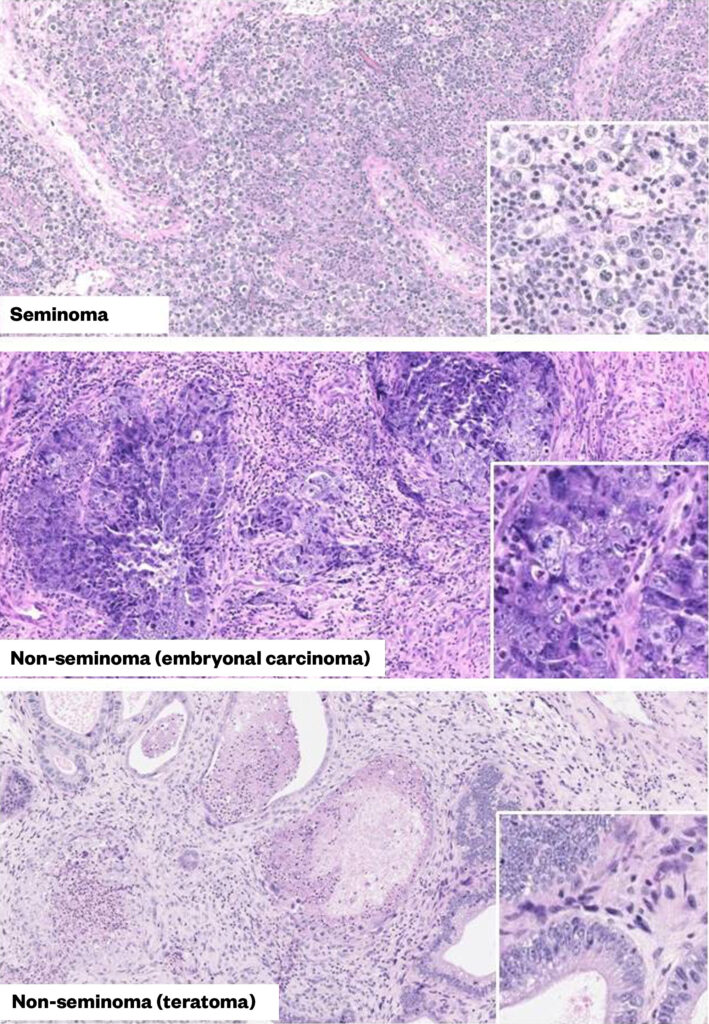

Testicular cancer is histologically divided into two primary types: seminomas and non-seminomas. Seminomas are composed of uniform germ cell-derived tumours, while non-seminomas are more diverse, featuring elements such as embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac tumours, choriocarcinoma and teratoma (see Figure 1)9. Non-seminomas often display a more aggressive course, comprising a mix of somatic and extra-embryonal components. Seminomas are most frequently diagnosed in males aged 25–40 years, whereas non-seminomas generally occur in younger men, typically from adolescence to age 30 years9. Both tumour types arise from germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS). Seminomas resemble immature germ cells, while non-seminomas show a variety of histological patterns, including undifferentiated embryonal carcinoma and partially differentiated somatic elements. Mixed or combined tumours, containing both seminoma and non-seminoma components, are classified and treated as non-seminomas, owing to their generally more aggressive clinical behaviour9.

Reproduced with permission from MDText.com

Staging

Once a testicular cancer is diagnosed, the cancer will be staged and classified based on pathology and extent of tumour spread. To assess the extent of the disease, the commonly used TNMS classification system shown in Table 1:

T – Size and extent of primary tumour;

N – Regional lymph node involvement;

M – Presence or absence of disease metastases;

S – Post-orchiectomy nadir (lowest level) of serum tumour marker levels (LDH, B-hCG and AFP)10.

The TNMS classification system can be used to guide the extent of the disease. The cancer is then staged between stages I-III, stage I being low volume and mostly locally confined disease to stage III being spread beyond retroperitoneal nodes with visceral metastatic disease, or local disease with significantly raised tumour markers. There is no prognostic stage IV disease in testicular cancer. The staging is shown in Table 210.

Once the cancer is staged and diagnosed, clinicians may use the International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group (IGCCCG) classification, shown in Table 3, for prognosis risk groups of metastatic disease10,12. This provides data on five-year progression-free survival and overall survival10,12.

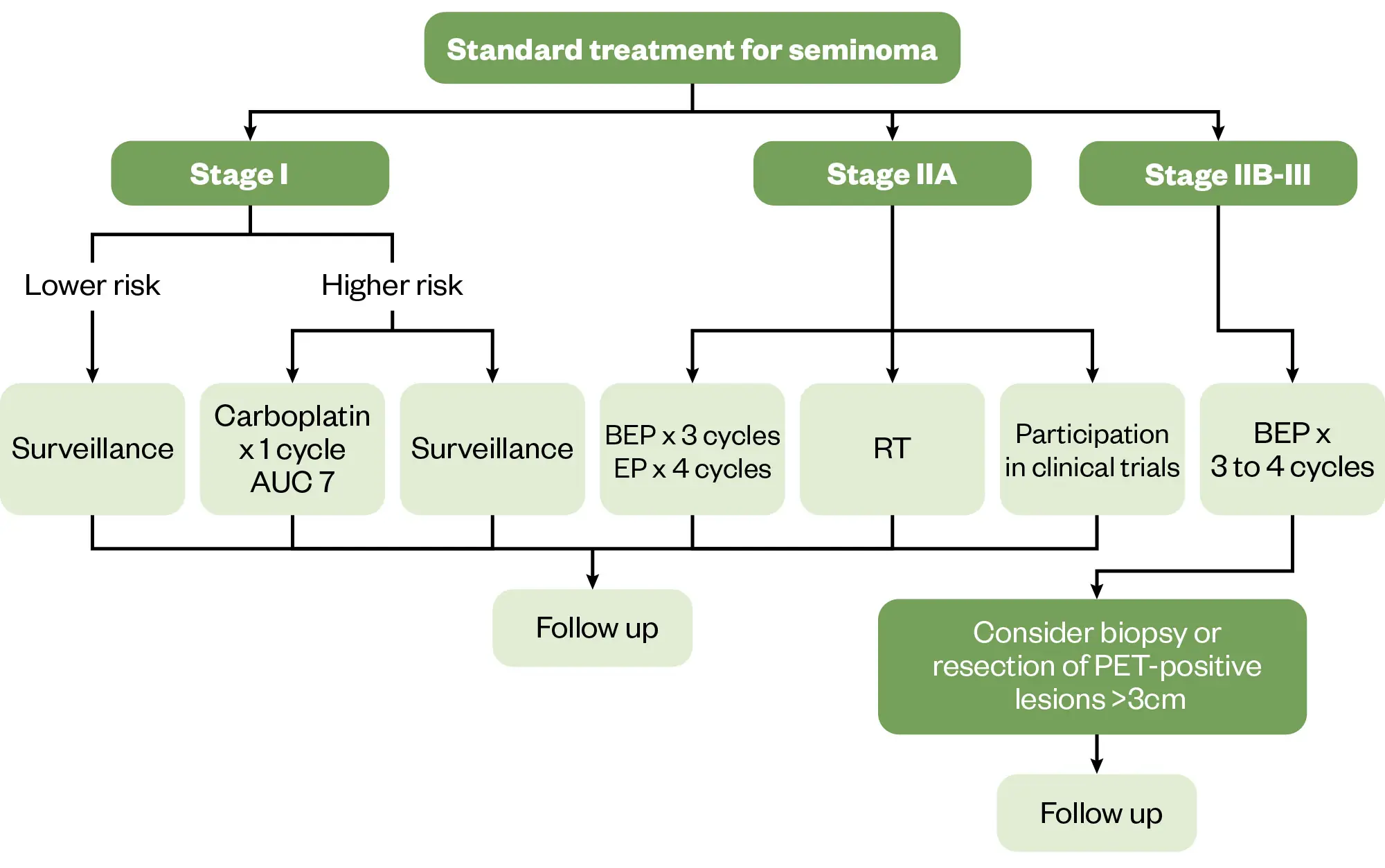

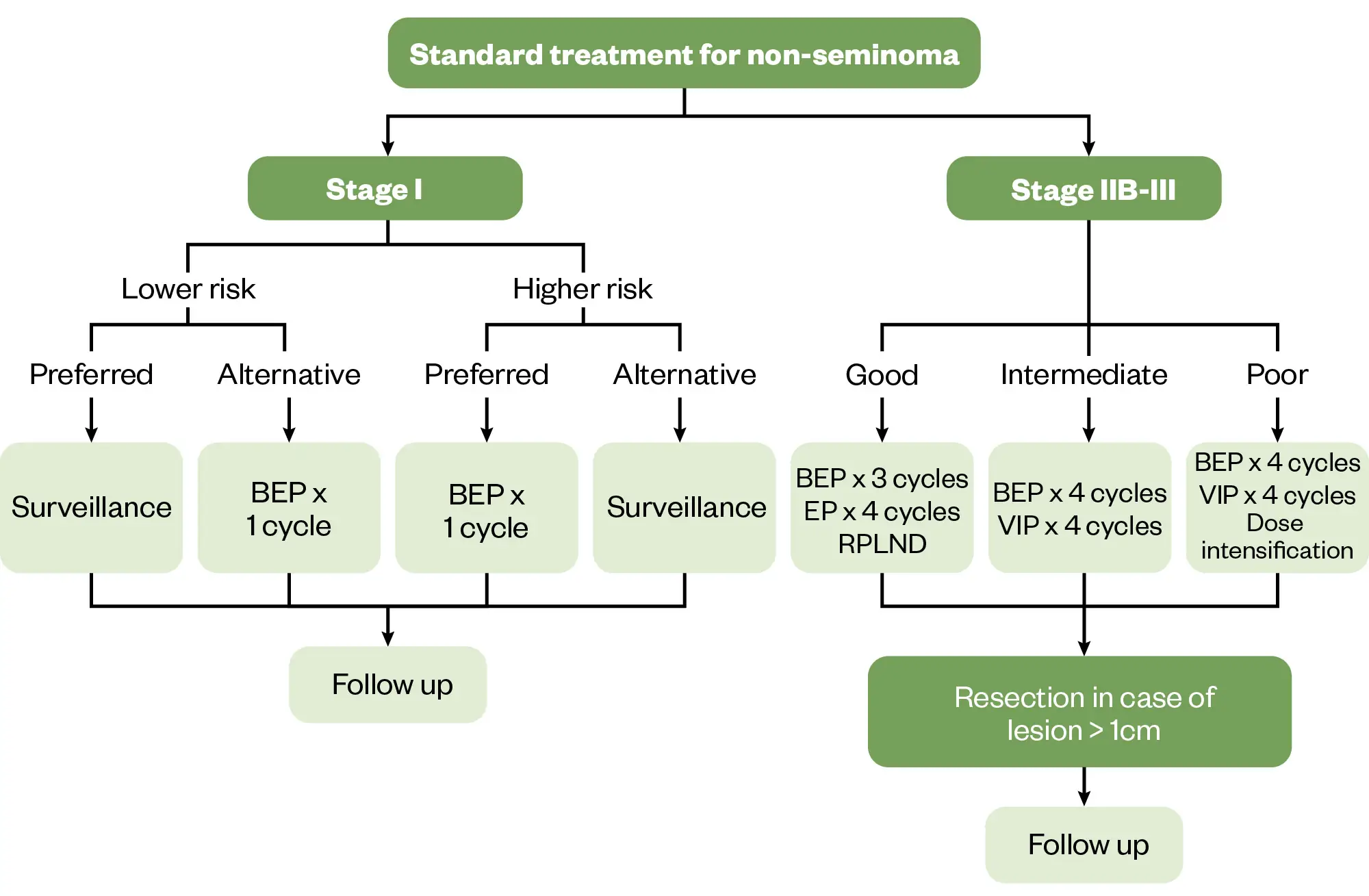

Management

Testicular cancer management is dependent on the stage and classification of the disease and prognostic assessments. Management may include surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, as appropriate12–14.

Surgery

Surgical intervention is the initial approach to aid with both diagnosis and treatment. The standard approach in the initial management of all testicular germ cell tumours is an orchidectomy (removal of the testicle) by a cut in the groin, including division of the spermatic cord. A scrotal approach (i.e. through the scrotum) should be avoided when testicular cancer is suspected, owing to its association with a higher rate of local recurrence10.

Testis sparing surgery (TSS) may be an option as an alternative to radical orchiectomy in patients who meet the following criteria:

- Patients wishing to preserve gonadal function with masses <2cm;

- Equivocal ultrasound/physical examination findings and negative tumour markers (human chorionic gonadotrophin [hCG] and alpha-fetoprotein [AFP]);

- Congenital, acquired or functionally solitary testis;

- Bilateral synchronous tumours (i.e. tumours that occur on both testes at the same time)6,16.

When TSS is done, multiple biopsies of the tissue from the opposing normal testicle are obtained in addition to the suspicious mass for evaluation simultaneously. Patients with testis preserved are at higher risk of local disease recurrence and need monitoring with physical examination and ultrasound frequently. SGCT patients should also be considered for adjuvant radiation when chemotherapy is inappropriate or declined. The impact of radiotherapy in reducing testosterone and sperm production and thus the risk of sub/infertility, hypogonadism and testicular atrophy should be discussed with the patient6,16,17.

Stage I seminoma germ cell tumour

Oncological outcomes of stage I seminoma germ cell tumours (SGCT) are favourable, regardless of initial management strategy. Following orchiectomy, patients with stage I disease have the option of surveillance, adjuvant carboplatin or adjuvant radiotherapy. Decisions about adjuvant treatment should be based on thorough discussions with the patient about the risks and benefits, including the fact that 80% of SGCTs are cured by orchiectomy alone and survival is almost 100% regardless of management10,18.

According to Groll et al., active surveillance following orchiectomy offers almost identical overall survival as adjuvant management strategies approaching 100%19. This involves a strict protocol of frequent imaging, monitoring of tumour markers and regular clinical assessments; the frequency of this monitoring will vary between patients. If follow-up compliance is questionable or if a surveillance strategy is not acceptable to the patient — owing to anxiety of recurrence or other reasons — a single dose of adjuvant carboplatin chemotherapy or adjuvant radiotherapy if unsuitable for chemotherapy may be used in stage I disease10.

Stage I non-seminoma germ cell testicular cancer

Management of stage I non-seminoma germ cell tumours (NSGCTs) takes a risk-adapted approach and includes surveillance or adjuvant chemotherapy. Around 70% of stage I NSGCTs are cured with orchiectomy alone and so this is the preferred option for patients in whom the tumour has not invaded local structures (i.e. no spermatic cord or scrotal involvement). For patients presenting with high-risk features, such as lymphovascular invasion or spermatic or scrotal invasion, or substantial component of embryonal carcinoma, there is much higher relapse rate, which can be up to 50% compared with 15% in tumours without these features3,6,20. In these patients, adjuvant treatment should be considered.

Treatment includes adjuvant chemotherapy in the form of one or two cycles of bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP), or a retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) after orchiectomy if patients are unsuitable for chemotherapy or unlikely to adhere to follow up. RPLND is a surgical removal of the lymph nodes from the back of the abdomen (as the testicular cancer can commonly spread to these nodes) and is less commonly used owing to the high survival rates of surveillance and lower relapse rates of cisplatin-based chemotherapy6,10,21.

Metastatic germ cell tumours

Initial management of metastatic disease is guided by histology of the primary tumour, tumour markers and prognostic groups defined in Table 310,12.

Combination chemotherapy is the standard approach for the management of metastatic disease. Generally, BEP is the preferred chemotherapy regime (three to four cycles). A combination of etoposide, cisplatin and ifosfamide (VIP) has comparable response rates to BEP; however, it is associated with more side effects, such as profound haematuria , nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity. In some cases, such as in poor prognosis groups, VIP may be used10,17.

To prevent the potential fatal risk of haemorrhagic cystitis secondary to ifosfamide, patients are treated with the cytoprotectant mesna, which binds to and deactivates acrolein (the urotoxic metabolite of ifosfamide in the urinary bladder)10,21.

BEP chemotherapy also has a variety of notable side effects. One of the primary concerns is myelosuppression, leading to neutropenia, anaemia and thrombocytopenia, which can heighten the risk of infections, fatigue and bleeding. Patients are routinely given granulocyte-stimulating factors (GCSF), such as filgrastim, to help boost white cells during the ‘nadir’ period when the chemotherapy causes them to be at their lowest, to help reduce the risk of serious infections during their treatment cycle10,22. Additionally, Bleomycin may cause pulmonary toxicity, resulting in pneumonitis and, in severe cases, pulmonary fibrosis10,22. Cisplatin is associated with nephrotoxicity, leading to renal impairment and electrolyte imbalances, such as hypomagnesemia and hypokalaemia, as well as ototoxicity, which can manifest as hearing loss or tinnitus10,22. Neurotoxicity, particularly peripheral neuropathy, is another potential issue with cisplatin. Nausea and vomiting are common side effects but can usually be managed with antiemetics. Patients may also experience mucositis and stomatitis from etoposide, which can impact the mouth and gastrointestinal tract, along with hair loss (alopecia)10,22. Furthermore, bleomycin can trigger hypersensitivity reactions, including fever and rash, and so is normally administered with steroids to prevent this.

Overall, fatigue is prevalent among patients undergoing this treatment10,22. To effectively manage these risks, it is crucial to closely monitor renal function, blood counts, pulmonary status and hearing throughout the course of therapy. In some cases, dose modifications of the chemotherapy may be considered to help mitigate the side effects and enable patients to tolerate their intended number of cycles of treatment10.

Response to treatment should be assessed after the induction chemotherapy by repeating imaging and tumour markers. In some cases, there may be residual tumours post-chemotherapy. In NSGCT, the tumour should be surgically resected where possible, rather than additional rounds of chemotherapy, as long as tumour markers have normalised. In SGCT, PET imaging may be used to assess activity of residual disease. Surgical resection may be challenging owing to the subtype of cancer; if the residual mass in these patients is <3cm then careful surveillance may be adopted, but masses beyond 3cm and those with rising tumour markers should be considered for further chemotherapy10,21.

The Pharmaceutical Journal

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Relapsed disease

Unlike most other cancers, some testicular cancer patients with relapsed disease may be cured with second-line salvage chemotherapy (around 50%)23,24. The chemotherapy used in these patients includes VeIP (ifosfamide, vinblastine and cisplatin) or TIP (paclitaxel, ifosfamide and cisplatin)10,21.

Some patients may be offered high-dose chemotherapy comprising sequential carboplatin and etoposide (CE) with autologous stem cell transplant support. The decision to treat with conventional chemotherapy versus high-dose chemotherapy is multifactorial and influenced by timing of relapse (i.e. whether it is more than or less than two years after primary treatment)10,21.

Germ cell neoplasia in-situ

Germ cell neoplasia in-situ (GCNIS) is a rare precursor of testicular cancers found in 0.4–0.8% of men and is currently unclassified into a stage25. It is non-invasive because the neoplastic cells are confined within seminiferous tubules of the testicles. It is usually asymptomatic and management options include orchidectomy or close observation, as the five-year risk of developing testicular cancer is 50%26. In solitary testis, local radiotherapy should be considered, noting that this will cause infertility10.

Side effects

The chemotherapy regimens used are all highly emetogenic so are prescribed alongside combination anti-emetics, such as 5HT antagonists (e.g. ondansetron), NK1 antagonists (e.g. aprepitant), metoclopramide, domperidone and steroids. In severe nausea and vomiting, patients may also be given olanzapine or levomepromazine27. Management of chemotherapy side effects can be seen in Table 5 and 66,10,12,27,28.

Supporting patients

Psychological support

Receiving a cancer diagnosis can be profoundly traumatic and emotional, with these feelings often heightened by treatment and its side effects. It is crucial to provide patients with robust support throughout their journey. Men may struggle to express their emotions owing to societal stigma and pressures29.

Cancer centres typically offer a variety of resources, so it is advisable to refer patients to clinical nurse specialists who can provide comprehensive information. Counselling services for both patients and their families, as well as support groups, can be invaluable in helping them navigate this challenging time.

Charities also play a vital role in offering information and services. Pharmacists can direct patients to relevant charity websites, including:

- Macmillan Cancer Support;

- Cancer Research UK;

- Testicular Cancer UK;

- Orchid Fighting Male Cancer;

- It’s in the Bag;

- Baggy Trousers UK;

- Movember;

Fertility

The removal of one testicle typically does not affect fertility, but the removal of both will result in infertility. RPLND may impact ejaculation, making natural conception less likely30.

Chemotherapy can reduce or impair sperm production, but fertility usually returns after treatment. However, some patients remain infertile, especially those who have received high doses of chemotherapy. Radiotherapy may cause temporary sperm damage to the healthy testicle; however, generally there are no long-term effects30.

The oncology team should discuss the option of a sperm bank with patients before treatment, addressing storage, duration, posthumous decisions and potential use for research or donation30.

To reduce the risk of birth defects, patients should be counselled to use reliable contraception during treatment and for six months after chemotherapy or one year after radiotherapy. While men treated for testicular cancer have a lower paternity rate after ten years compared with the general population, around 70% of those wishing to have children can still do so30.

Transgender patients

It is important to acknowledge and empathise with transgender patients to ensure they understand their cancer and feel comfortable with the care provided. Open communication is crucial in understanding what they are and are not comfortable with. Fostering an environment of understanding and respect will enhance the quality of care provided to all patients3.

The following resources are recommended for readers wanting to learn more about how pharmacists can best support transgender patients:

- ‘Best practice principles for inclusive care of transgender and non-binary patients‘;

- ‘TRANS:cribbing: clinical considerations for safe and inclusive prescribing for transgender and non-binary patients‘.

Best practice

- Testicular cancer is rare, but can be curable with early detection; therefore, it is crucial that patients are referred in a timely manner;

- The management of testicular cancer depends on the type and stage;

- Most of the chemotherapy used to treat testicular cancer is highly toxic with a large number of side effects. Medications such as anti-emetics, pain relief and GCSF are crucial to support the patient’s journey;

- Some of the treatments have very dangerous side effects, such as pulmonary toxicity with bleomycin. It is important to refer patients to urgent care if you recognise signs of this.

- 1.Testicular cancer statistics. Cancer Research UK. Accessed January 2025. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/testicular-cancer#:~:text=In%20males%20in%20the%20UK,UK%20(2016%2D2018)

- 2.Testicular cancer. Macmillan Cancer Support. Accessed January 2025. https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/testicular-cancer

- 3.Testicular Cancer Symptoms. Testicular Cancer UK. Accessed January 2025. https://www.testicularcanceruk.com/testicular-cancer-symptoms

- 4.Scenario: Testicular cancer. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2024. Accessed January 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/scrotal-pain-swelling/management/testicular-cancer/

- 5.Ferguson L, Agoulnik AI. Testicular Cancer and Cryptorchidism. Front Endocrinol. 2013;4. doi:10.3389/fendo.2013.00032

- 6.Testicular cancer. BMJ Best Practice. January 2024. Accessed January 2025. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/255

- 7.What is testicular cancer? University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Accessed January 2025. https://www.uclh.nhs.uk/our-services/find-service/cancer-services/testicular-cancer-1/what-testicular-cancer

- 8.Powles T, Bower M, Daugaard G, et al. Multicenter Study of Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Related Germ Cell Tumors. JCO. 2003;21(10):1922-1927. doi:10.1200/jco.2003.09.107

- 9.Feingold K, Anawalt B, Blackman M, et al. endotext. Published online March 29, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278992/

- 10.EAU Guidelines on Testicular Cancer. European Association of Urology. 2024. Accessed January 2025. https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Testicular-Cancer-2024.pdf

- 11.Dogra V, Bhatt S. Acute painful scrotum. Radiologic Clinics of North America. 2004;42(2):349-363. doi:10.1016/j.rcl.2003.12.002

- 12.Clinical Practice Guideline – Testicular Seminoma and Non-Seminoma. European Society for Medical Oncology. 2022. Accessed January 2025. https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/guidelines-by-topic/esmo-clinical-practice-guidelines-genitourinary-cancers/testicular-cancer

- 13.Mead GM, Fossa SD, Oliver RTD, et al. Randomized Trials in 2466 Patients With Stage I Seminoma: Patterns of Relapse and Follow-up. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2011;103(3):241-249. doi:10.1093/jnci/djq525

- 14.Kondagunta GV, Bacik J, Bajorin D, et al. Etoposide and Cisplatin Chemotherapy for Metastatic Good-Risk Germ Cell Tumors. JCO. 2005;23(36):9290-9294. doi:10.1200/jco.2005.03.6616

- 15.Stephenson A, Bass EB, Bixler BR, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Early-Stage Testicular Cancer: AUA Guideline Amendment 2023. Journal of Urology. 2024;211(1):20-25. doi:10.1097/ju.0000000000003694

- 16.Patel HD, Gupta M, Cheaib JG, et al. Testis-sparing surgery and scrotal violation for testicular masses suspicious for malignancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 2020;38(5):344-353. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.02.023

- 17.West Midlands Expert Advisory Group for Urological Cancer. Guidelines for the Management of Testicular Cancer. NHS England. 2016. Accessed January 2025. https://www.england.nhs.uk/mids-east/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2018/05/guidelines-for-the-management-of-testicular-cancer.pdf

- 18.Ruf CG, Schmidt S, Kliesch S, et al. Testicular germ cell tumours’ clinical stage I: comparison of surveillance with adjuvant treatment strategies regarding recurrence rates and overall survival—a systematic review. World J Urol. 2022;40(12):2889-2900. doi:10.1007/s00345-022-04145-6

- 19.Groll RJ, Warde P, Jewett MAS. A comprehensive systematic review of testicular germ cell tumor surveillance. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2007;64(3):182-197. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.04.014

- 20.Daugaard G, Gundgaard MG, Mortensen MS, et al. Surveillance for Stage I Nonseminoma Testicular Cancer: Outcomes and Long-Term Follow-Up in a Population-Based Cohort. JCO. 2014;32(34):3817-3823. doi:10.1200/jco.2013.53.5831

- 21.Oldenburg J, Berney DM, Bokemeyer C, et al. Testicular seminoma and non-seminoma: ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology. 2022;33(4):362-375. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2022.01.002

- 22.Bleomycin, etoposide and platinum (BEP). Cancer Research UK. 2023. Accessed January 2025. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/bep#:~:text=BEP%20is%20a%20chemotherapy%20combination,you%20pronounce%20it%20in%20brackets.&text=Doctors%20also%20use%20BEP%20to,and%20sex%20cord%20stromal%20tumours

- 23.Voss MH, Feldman DR, Bosl GJ, Motzer RJ. A Review of Second-line Chemotherapy and Prognostic Models for Disseminated Germ Cell Tumors. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 2011;25(3):557-576. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2011.03.007

- 24.Rashdan S, Einhorn LH. Salvage Therapy for Patients With Germ Cell Tumor. JOP. 2016;12(5):437-443. doi:10.1200/jop.2016.011411

- 25.Spiller CM, Bowles J. Germ cell neoplasia in situ: The precursor cell for invasive germ cell tumors of the testis. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2017;86:22-25. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2017.03.004

- 26.Hoei-Hansen CE, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Daugaard G, Skakkebaek NE. Carcinoma in situ testis, the progenitor of testicular germ cell tumours: a clinical review. Annals of Oncology. 2005;16(6):863-868. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdi175

- 27.Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Basch E, et al. Antiemetics: ASCO Guideline Update. JCO. 2020;38(24):2782-2797. doi:10.1200/jco.20.01296

- 28.Chemotherapy side effects. Macmillan Cancer Support. Accessed January 2025. https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/treatment/types-of-treatment/chemotherapy/side-effects-of-chemotherapy

- 29.Movember. November. Accessed January 2025. https://uk.movember.com/

- 30.Testicular Cancer: A Guide for Patients. European Society for Medical Oncology. 2019. Accessed January 2025. https://www.esmo.org/for-patients/patient-guides/testicular-cancer