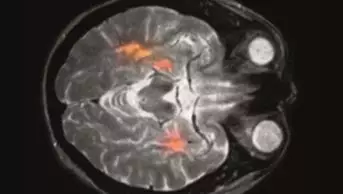

Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

There is “good evidence” to suggest that drugs commonly used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may also improve general cognition and symptoms of apathy in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, UK researchers say.

Combined data from several randomised controlled trials that had been carried out to test the effect of noradrenergic drugs on cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as agitation and apathy, in people with the neurodegenerative disease showed some promising results, the researchers reported in the Journal of Neurology, Neuroscience and Psychiatry on 5 July 2022.

The results of 10 trials of 1,300 patients with Alzheimer’s disease conducted over a 40-year period, which looked at the impact of the drugs on attention, memory, verbal fluency, language and visuospatial ability, showed a small, but significant, positive effect on overall cognition compared with placebo, as measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination or the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale.

Further analysis of results from 8 clinical trials, involving 425 patients with Alzheimer’s disease, looking at behaviour and neuropsychiatric symptoms, showed a large positive effect of noradrenergic drugs on apathy. But the researchers noted that no effect was seen on overall measures of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

The researchers explained that noradrenergic dysfunction occurs early in Alzheimer’s disease and contributes to cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Yet current symptomatic treatments of Alzheimer’s disease focus on restoration of cholinergic and glutamatergic systems, with only modest effects.

“This meta-analysis suggests that drug repurposing with established noradrenergic treatments, such as atomoxetine, methylphenidate and guanfacine, may benefit people with Alzheimer’s disease, particularly given existing evidence of their relative safety in clinical practice, and pharmacological target engagement,” the researchers concluded.

“Repurposing of established noradrenergic drugs is most likely to offer effective treatment in Alzheimer’s disease for general cognition and apathy,” they added. “These therapies do not appear to have any beneficial effects on attention or episodic memory.”

The findings provide strong rationale for further, targeted clinical trials of noradrenergic treatments in Alzheimer’s disease, the researchers said, but because of the variability seen in the studies they analysed, clinical trials would need to be carefully designed.

Aspects such as appropriate targeting of particular patient groups and understanding the dose effects of individual drugs and their interactions would need to be taken into account should more research be done.

Dr Rosa Sancho, head of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK, said there were currently 143 drugs in clinical trials for Alzheimer’s and, while some counteract symptoms, most target the various biological processes that could be driving the disease.

“There is currently a lack of drugs approved to treat apathy in Alzheimer’s, a symptom that has been linked to lower quality of life, faster decline and increased stress for carers.

“This well-conducted meta-analysis highlights the potential of noradrenergic drugs to treat some aspects of Alzheimer’s, but the evidence in the trials reviewed here varies in quality and it’s hard to directly compare results from each study because the methods used are not consistent.”

She added: “While there are limitations to the evidence reviewed in this paper, it highlights a need for well-conducted clinical trials to determine whether drugs that already treat conditions like ADHD could be safe and beneficial for people with Alzheimer’s. Research like this will help keep people connected to their families, their worlds and themselves for longer.”

You may also be interested in

Headache: recognition and management

Cannabinoids have limited impact on MS symptoms