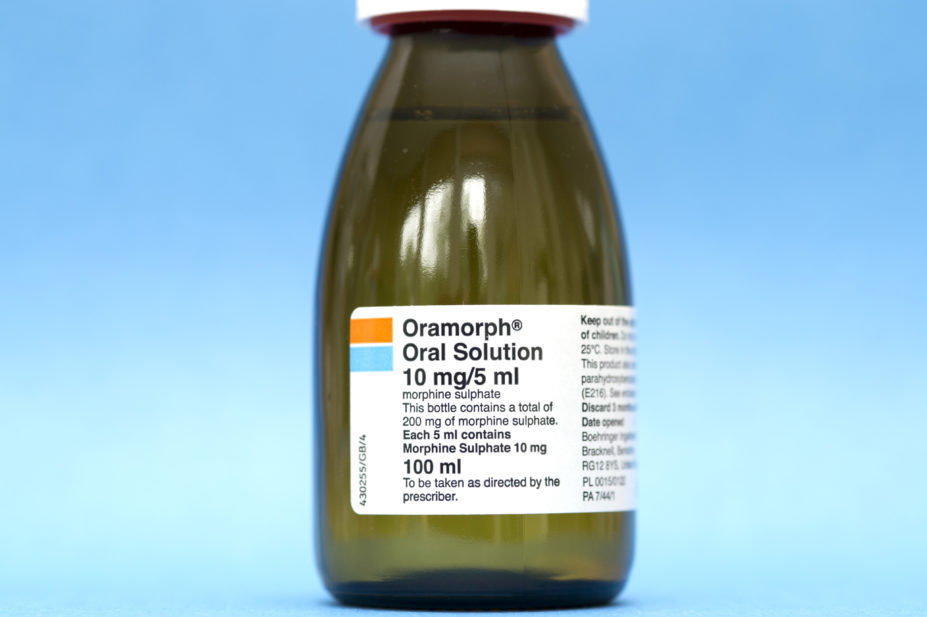

Dr P Marazzi / Science Photo Library

An analysis of all coroner’s reports published on the Courts and Tribunals Judiciary website since 2013 by The Pharmaceutical Journal has revealed that liquid morphine has contributed to the cause of death in at least three men and ten women since 2013.

Coroners have raised specific concerns about liquid morphine — under the brand name Oramorph — on six occasions and, in three cases, coroners were so concerned about the risk of accidental death or abuse they appealed for healthcare bodies and government departments to put in place additional restrictions.

However, to date, no additional restrictions have been introduced by the Home Office.

The concerns were raised in ‘prevention of future deaths’ reports that were drawn up by coroners after their inquests had concluded. The reports were then sent on to healthcare bodies and government departments for consideration.

Most recently, in April 2021, the death Helen Spicer, aged 43 years, at Royal Cornwall Hospital in Truro was ruled by a coroner as a “drug-related death” owing to an unintentional overdose of Oramorph. The report pointed out that the coroner was unable to determine who collected the prescription because there was no requirement for it “to be signed for”.

Liquid morphine is used to relieve severe pain, such as that associated with cancer, severe injury and surgery, but under the Misuse of Drugs Act, Oramorph 0.2% is currently a schedule 5 controlled drug — along with codeine tablets and other diluted forms of schedule 2 drugs — unlike other forms of morphine, which are classed schedule 2.

This means that pharmacies are not required to keep documentation relating to the drug for longer than two years or carry out identity checks of the person collecting the prescription.

John Hughes, dean of the Faculty of Pain Medicine of the Royal College of Anaesthetists, said the coroners were correct to raise concerns. He said: “Although the concentration of the oral morphine solution is relatively low, the 100mL, 300mL and 500mL prescribable volumes available provide a total dose of 200mg, 600mg and 1000mg which allow for a significant risk of harm, misuse or misappropriation.”

Cathy Price and Michael Serpell, trustees at Pain Concern — a charity for patients experiencing pain — added that although 0.2% morphine sounds weak, “if taken in large volumes it carries a potentially very high dose of morphine”. “It doesn’t make pharmacological sense to categorise it as schedule 5, without stating a limit to the amount or volume of the drug,” they added.

Cathy Stannard, a consultant in complex pain at NHS Gloucestershire Clinical Commissioning Group and clinical lead for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline on chronic pain, added that it “makes sense” for Oramorph to be more tightly controlled. “[Oramorph is] particularly problematic because it’s a liquid and people swig it, so that means there’s a lack of control over dose when people are taking it,” she said. “It’s more of a challenge to measure out the right dose than it is to pop a pill out of a strip.”

A spokesperson for the Home Office said: “Any death due to drug misuse is a tragedy. The government’s approach remains clear — we must prevent drug misuse in our communities and support people through treatment and recovery.

“While there are no plans at present to consider the rescheduling of oral morphine, we continue to work closely with the Department of Health and Social Care in understanding the complex factors involved in addition, and protect individuals from these harms.”

The spokesperson added that Project ADDER “will combine stepped up enforcement with more rehabilitation for those with addictions in the hardest-hit areas in England and Wales”.

In January 2021, the government invested £28m into piloting Project ADDER, which combines tougher policing with enhanced treatment and recovery services.