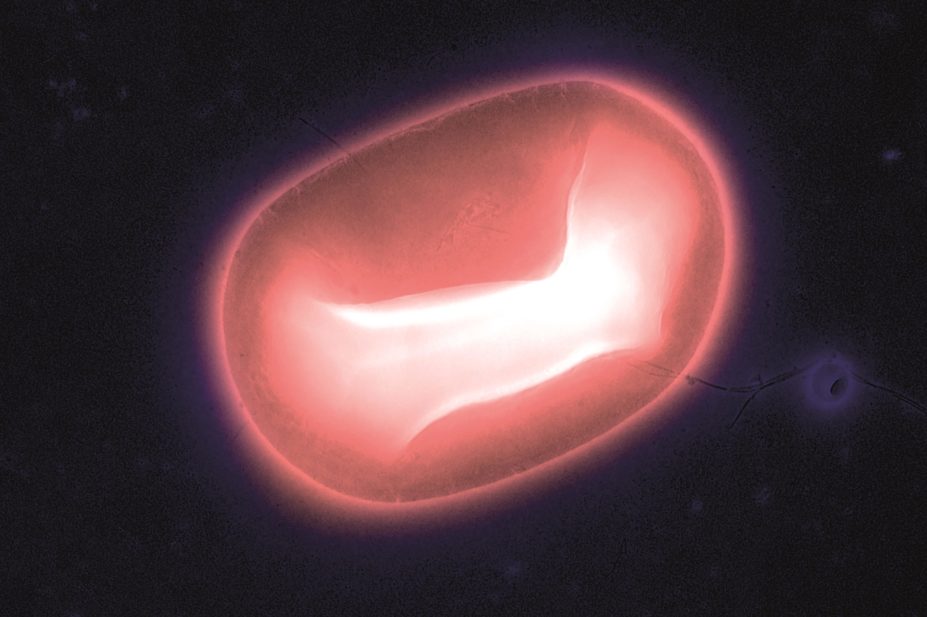

Courtesy of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies

A strain of Escherichia coli in the guts of mice appears to protect them from muscle wasting associated with infection and inflammatory bowel disease, according to research published in Science

[1]

on 29 October 2015.

Researchers at the Salk Institute, California, believe that if a similar strain can be found in humans then it could provide an alternative to antibiotics. The E. coli strain identified in mice — called O21:H — does not fight off the infection, but it prevents some of the most damaging side effects of infection.

“Treatments for infection have long focused on eradicating the offending microbe, but what actually kills people aren’t the bacteria themselves — it’s the collateral damage it does to the body,” says lead author Janelle Ayres, a Salk assistant professor in the Nomis Foundation Laboratories for immunobiology and microbial pathogenesis.

Disease-free mice colonised with the protective bacteria showed no difference in weight, muscle mass or food consumption compared with mice without the protective bacteria. But when the mice were challenged with either Salmonella intestinal infection or Burkholderia lung infection they were protected from muscle wasting, despite exhibiting the same levels of inflammation and energy uptake as mice without the protective E. coli strain. Mice with sepsis were also protected from muscle wasting.

The protective E. coli strain was in fact found to migrate to the white fat cells where it maintains the insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) signalling pathway in these cells. The IGF-1 signalling pathway is essential for maintenance of muscle mass. Ordinarily, during infection and inflammatory bowel conditions this signalling pathway is downregulated, allowing the activation of other pathways that contribute to muscle wasting.

“This is an important discovery,” says Joaquin Madrenas, director of the Microbiome and Disease Tolerance Centre, McGill University, Canada, who was not involved in the research. “It moves the research on the gut microbiome forward by going deeper into mechanisms of action.” However, he warns that the same effect may not be seen in humans, as the microbiome profile may differ. He suggests that this signalling pathway could be targeted by several drugs, some of which are currently being tested in other conditions, including cancer.

Mice given the chemical DSS, which causes damage similar to that seen in inflammatory bowel disease and Crohn’s, all died within 12 days when they were not colonised with E. coli O21:H. In contrast, 70% of the E. coli O21:H mice survived.

The team at the Salk institute are now trying to find out if the protective E. coli strain is able to fend off the damage caused by infection for long enough to allow the body to fight off the infectious pathogen. Madrenas says the next challenge will be to identify exactly which metabolite from the microbes confers the protection.

- This article was updated on 3 November 2015 to change the image

References

[1] Palaferri Schieber AM, Lee YM, Chang MW et al. Disease tolerance mediated by microbiome E. coli via inflammasome and IGF-1 signaling. Science 2015. doi:10.1126/science.aac6468