MAG

When most people think about consuming a vegan or vegetarian diet, their medicines are perhaps not the first thing that come to mind. However, many medicines contain excipients that are derived from animals, making it difficult for most people to avoid animal products entirely — but this might be starting to change.

In February 2022, the world’s first medicine to be certified to contain no animal-derived products by The Vegan Society went on sale in Germany. Paraveganio, a paracetamol product manufactured by Hamburg-based wholesaler Axunio, uses a plant-based source of the excipient magnesium stearate.

“The needs and preferences of vegan people are currently completely being flouted,” says Julia von Horsten, the company’s product and business development manager.

We wanted to give them access to the first certified vegan product … to pave the way to more transparency and awareness for the vegan lifestyle within the pharma sector

Julia von Horsten, product and business development manager at Axunio

“For that reason, we wanted to give them access to the first certified vegan product and pave the way to more transparency and awareness for the vegan lifestyle within the pharma sector.”

Veganism and vegetarianism have grown in popularity over recent years, with initiatives such as ‘Veganuary’ and climate change concerns helping to promote these as lifestyle choices (see Box).

Box: Avoiding animal products

The number of vegans in the UK has quadrupled over a five-year period.

According to a survey organised by the Food Standards Agency and the National Centre for Social Science Research, approximately 150,000 people considered themselves vegans in 2014[1]. By 2019, a survey by Ipsos Mori for The Vegan Society revealed that this number had risen to around 600,000[2].

The Cambridge Dictionary defines a vegan as someone ‘who does not eat or use any animal products such as meat, fish, eggs, cheese or leather’, while a vegetarian is defined as a person ‘who does not eat meat for health or religious reasons, or because they want to avoid being cruel to animals’.

And, although the dictionary definitions may not mention medicines, many people living a vegan or vegetarian lifestyle aim to avoid animal products wherever possible. Faiths including Judaism, Hinduism, Islam and Buddhism also teach that certain animal products should not be taken into the body, and this includes in drug form.

Animal products in medicines

Nevertheless, it is difficult for vegans and vegetarians, as well as those practising religions that forbid some consumption of animal products, to know which medicines align with their beliefs.

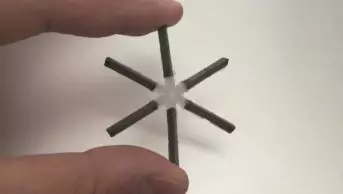

Research published in The BMJ in 2014 showed that 74 of the 100 most commonly prescribed medicines in primary care contained one or more of the excipients lactose, gelatine or magnesium stearate (see Figure)[3]. Lactose was found in 59 of the drugs, magnesium stearate in 49 drugs, and gelatine in 20 drugs.

According to the Specialist Pharmacy Service (SPS), gelatine is often used in capsules, tablets, as part of modified release preparations, or to thicken liquids, and is usually derived from the skin and bone of cattle and pigs. Lactose, used as a diluent, is generally produced from milk[4]. And magnesium stearate, used in the production of both tablets and powders, is most commonly derived from bovine tallow, a form of beef fat, although it can also be produced from plants.

Both the summary of product characteristics (SPC) and patient information leaflet provided with all authorised drugs include a list of excipients, but it is not always possible to determine which ingredients are derived from animals from this information.

The Medicine and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency’s (MHRA’s) public assessment reports do provide information on the use of animal products, but these are only available for new marketing authorisations granted after 30 October 2005. And even then, researchers working on The BMJ article found that “these were inconsistent, incomplete, and on two occasions wrong”.

The SPS advises that to confirm the suitability of a product for use by someone who wants to avoid animal products “involves checking the licensed product information and contacting the manufacturer directly”.

However, it also warns: “Sometimes, pharmaceutical companies cannot guarantee or differentiate the specific sources of animal-derived ingredients, as various suppliers are used in the manufacturing process and the sources can change.”

Samantha Fry, a hospital pharmacist and vegan, advises patients to check the manufacturer’s website for information on branded products.

“The manufacturers are much the same as they have always been,” she says. “The ones that were always responsive and helpful still are and the others are still unhelpful.

“The best-case scenario is that the excipients listed are those that are simply not from animal sources. But this hasn’t changed over time as this still requires a working knowledge of how each excipient is manufactured.”

The British Generic Manufacturers Association confirms that “company medical information services can provide guidance on the suitability of individual medicines for vegetarians and vegans”.

‘The big three’

Kendal Pitt, senior technical director for solid oral dosage forms at the pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline, explains that magnesium stearate, gelatine and lactose are the “big three” in terms of animal-derived products in the production of medicines. The vast majority of active pharmaceutical ingredients are synthetically produced with very few from animals, he adds.

Most large drug companies have had a policy of removing animal products whenever they can for the last ten years, driven by public demand

Kendal Pitt, senior technical director for solid oral dosage forms at GlaxoSmithKline

“Most large drug companies have had a policy of removing animal products whenever they can for the last ten years, driven by public demand,” he explains.

Work on shifting magnesium stearate production away from animal products began 20 years ago, prompted by worries over transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSE), he says. Manufacturers have also been working on shifting from the use of hard gelatine, such as in capsules, initially to make sure that drugs were acceptable for people for religious reasons, because the main sources of gelatine are cows and pigs.

Lactose use has only recently come onto the radar, he says, but firms are now looking at vegan alternatives, which has caused a decline in lactose use across newly-marketed products.

Pitt says it is difficult to estimate the proportion of drugs that have removed all animal products from the manufacturing process, and there is no source of industry-wide data. As an indication, a search of the MHRA database of product information, carried out at the end of August 2022, shows that 2,732 products contain gelatine capsules in their SPC, compared with just 106 for hydroxypropylmethylcellulose (HMPC) capsules, one of the main vegan alternatives.

The limited uptake of alternatives to gelatine capsules may, in part, come down to difficulties with their use. For example, HMPC capsules can have reduced release rates of the medicine compared with gelatine capsules and can be brittle, causing challenges during large-scale manufacturing and potential leakage issues for patients[5].

Increasing demand

Pitt adds that when making medicines animal-free, it is generally simpler for manufacturers to bring new products to the market.

“A replacement for an existing product can trigger the need for a bioequivalent study, which can be expensive, and can make a switch uneconomic,” he explains.

He also says it is clear that the demand for vegan medicines has increased in recent years.

As veganism has grown so rapidly recently, there is the potential over the next five years for a jump in the number of patients who will expect a vegan option for their medication

Samantha Fry, hospital pharmacist and vegan

Fry agrees: “As veganism has grown so rapidly recently, there is the potential over the next five years for a jump in the number of patients who will expect a vegan option for their medication.

“Perhaps this will take longer as the average age of vegans is probably quite low and the effect on medication may not show until those vegans grow older.”

Axunio’s von Horsten, admits that sales of Paraveganio have so far been ‘medium’ in Germany.

“The key word here is ‘awareness’ — there are still too few people being aware that not every product containing paracetamol is vegan and that there is actually our vegan certified option,” she says.

Von Horsten says the company hopes to produce further vegan products in the future, but it currently has a portfolio of just two medicines.

Broadening access

In 2017, the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Vegetarianism and Veganism wrote to the then health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, calling on him to broaden access to existing animal-free prescription drugs[6]. They also wanted Hunt to introduce policies that would provide guidance for medical professionals when seeking consent from patients on the use of medicines containing animal products, and for manufacturers on food-style labelling of animal products in drugs.

In response to the 2014 article in The BMJ, the MHRA previously said that, as a member of the EU, the UK could not “unilaterally” introduce a labelling system for medicines. In addition, while clear information on the use of animal products in drugs had been discussed at a European level, the EU’s view was that this was a ‘lifestyle issue’, which it ruled out on the grounds that it would be impossible to draw up a labelling system that catered for a number of lifestyle issues[3].

In 2017, health minister Lord O’Shaughnessy replied to the APPG with the government’s position stating that: “Patients who wish to identify such products will need to rely on the information that can be provided directly by their pharmacist[5].”

“For new medicines coming to market there is an increasing tendency to avoid animal-derived ingredients. As technology advances, we expect that more non-animal-derived materials will become available. However, for some medicines, the avoidance of animal-derived components is currently not possible,” he added.

The MHRA would not provide comment to The Pharmaceutical Journal on whether it had considered introducing a new policy on such statements now that the UK has left the EU, but it says it does approve manufacturers’ statements that drugs are free of animal products if they can prove it.

For new medicines coming to market there is an increasing tendency to avoid animal-derived ingredients

Lord O’Shaughnessy, health minister between 2016 and 2018

“Where a company can demonstrate to MHRA that no products of animal origin have been used in the manufacture of the ingredients nor the medicine itself, they may include a statement such as ‘suitable for vegetarians/vegans’ or similar,” a spokesperson explains.

However, the spokesperson would not divulge how many products had been approved in this way.

The Human Medicines Regulations 2012 set out what information must appear on medicines labelling, but the legislation does not cover statements, such as whether or not a product includes animal products, because its focus is on safe and effective use of the product[7].

One of the biggest issues for patients who do not consume animal products is that they are simply unaware that many medicines would be unsuitable for them to take.

In 2004, a small study of 100 patients and 100 doctors in the United States found that 84% of patients were unaware that medicines included products derived from pork or beef, and 70% of doctors did not know that some drugs included animal-based products that would contravene their patients’ religious beliefs[8].

Fry says that the “vast majority” of vegan and vegetarian patients she speaks to have not thought about medicines as possibly containing animal products.

“Most have been happy to accept an approach of supplying a vegan or vegetarian formulation where possible and not worrying about the ones that can’t be changed.

“All have been unbelievably grateful that we took the time to have the conversation, but it is a huge time pressure when it happens.”

She is hopeful that a rise in veganism will see the attitude among manufacturers to animal products in medicines continue to evolve, but she warns: “Until patients start demanding this in bigger numbers, I don’t think the situation will change.”

- 1The 2014 Food and You Survey . GOV.UK. 2014.https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/food-and-you-2014-uk-bulletin-1.pdf (accessed 2 Sep 2022).

- 2Worldwide growth of veganism. The Vegan Society. https://www.vegansociety.com/news/media/statistics/worldwide#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20vegans%20in,150%2C000%20(0.25%25)%20in%202014. (accessed 2 Sep 2022).

- 3Tatham KC, Patel KP. Suitability of common drugs for patients who avoid animal products. BMJ. 2014;348:g401–g401. doi:10.1136/bmj.g401

- 4Excipients: What are the general considerations for vegan patients? Specialist Pharmacy Service. 2019.https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/excipients-what-are-the-general-considerations-for-vegan-patients/ (accessed 2 Sep 2022).

- 5O’Shaughnessy J. Letter from Lord James O’Shaughnessy. Department of Health. 2017.https://www.vegansociety.com/sites/default/files/DH%20reply%20to%20APPG%20letter.pdf (accessed 2 Sep 2022).

- 6Make More Medicines Vegan. The Vegan Society. https://www.vegansociety.com/take-action/campaigns/make-more-medicines-vegan#:~:text=The%20Vegan%20Society%20is%20calling,it%20comes%20to%20taking%20medicines.&text=Government%20to%20find%20out%20what,them%20in%20across%20the%20board. (accessed 2 Sep 2022).

- 7The Human Medicines Regulations 2012. legislation.gov.uk. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2012/1916/contents/made (accessed 2 Sep 2022).

- 8Sattar SP, Ahmed MS, Madison J, et al. Patient and Physician Attitudes to Using Medications with Religiously Forbidden Ingredients. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:1830–5. doi:10.1345/aph.1e001

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

The contents of medicines are surely only part of the story. What about the research on laboratory animals that is used to ensure safety, lack of toxicity, and effectiveness?