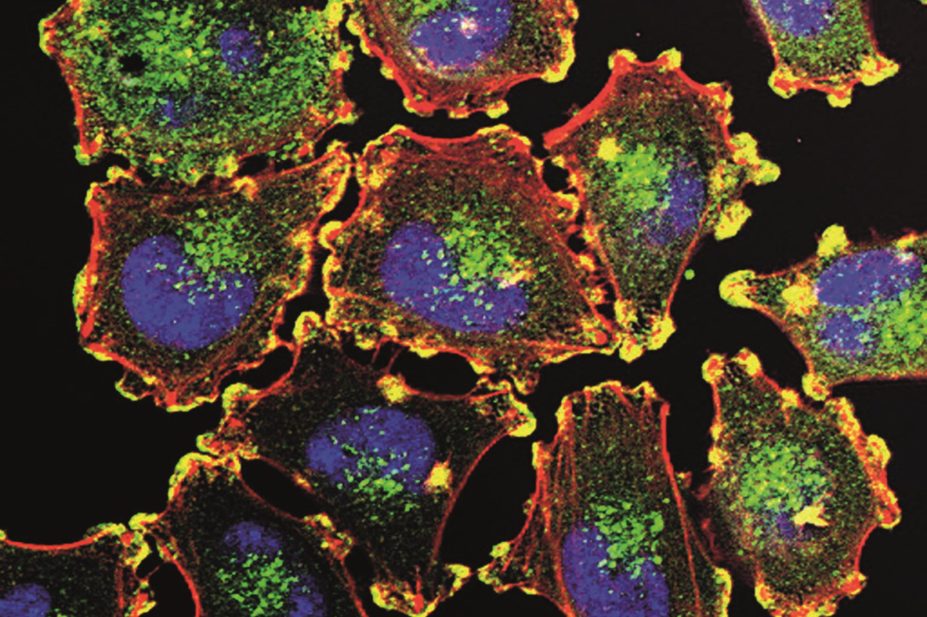

National Cancer Institute

A study by UK researchers has found a possible explanation for a reported link between aspirin and a reduced risk of cancer. It also points to novel disease biomarkers and a useful addition to the arsenal of conventional and immune-based cancer therapies.

Caetano Reis e Sousa at the Francis Crick Institute in London and colleagues have found that some tumour cells produce significant levels of a molecule called prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). PGE2 is produced by the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX) and dampens the immune system’s normal response employed to attack faulty cells.

The research was based primarily on mouse melanoma, but the research team also looked at human melanoma biopsies and found that the COX-dependent inflammatory signature was markedly similar in mice and men, suggesting that this is a highly conserved response. Based on this, Reis e Sousa’s team argues that COX activity is a driver of immune suppression across species.

Tumour cells that produce sufficient PGE2 are able to evade a patient’s immune defences. Many immunotherapies used to treat cancer, which are designed to boost the patient’s own immune response to fight off tumour cells, are not as effective as might be expected. Reis e Sousa’s team suggests this could be attributed to tumour cells producing increased PGE2 and fighting off even this therapeutically-amplified immune response. Knowing which tumour cells produce sufficient levels of PGE2 to thwart immune defence could help clinicians predict which tumours will respond favourably, and which will not, to a given immunotherapy.

Aspirin, a COX inhibitor, is known to stop the production of PGE2 and help boost the immune system. Reis e Sousa’s team found that putting aspirin in the drinking water of mice had no effect on melanoma cells that had been implanted in the mice. However, when it was combined with an immunotherapy (anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody), tumour cells were eradicated much more quickly than with immunotherapy alone.

“These findings have obvious therapeutic implications,” writes Reis e Sousa in Cell

[1]

on 3 September 2015. Treating patients with aspirin alongside immunotherapy could make a huge difference to the benefits associated with treatment, he says. “It’s early work but this could help make cancer immunotherapy even more effective.”

In 2013, a US research group at Stanford University School of Medicine discovered that women who took aspirin on a regular basis reduced their risk of developing melanoma.

“We don’t know how much aspirin should be taken, or for how long, to be most effective,” said lead researcher, Jean Tang, at the time. She was also mindful of the well-known side effects of aspirin use — stomach complaints, ulcers and bleeding. “Our aim is to find a drug or agent that is readily available, and that will be well-tolerated, safe to use and protective against cancer development,” said Tang.

References

[1] Zelenay S, van der Veen AG, Böttcher JP et al. Cyclooxygenase-dependent tumor growth through evasion of immunity. Cell 2015;162:1–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.015.