Most people would not dream of swallowing something which tasted strange, or was in some way peculiar. However, pharmacists’ medicines fall into exactly those categories. Pharmacists must persuade their clients that medicines are safe to take and for

that, pharmacists must be trusted.

Their clients’ mouth is a kind of judgement chamber, and only if an object is considered safe, does it pass the lips. If it tastes safe it is then judged to be safe, and subsequently swallowed.

The first decision is whether to place a substance within the mouth at all. Babies insert anything, experimentally, and soon learn that some things are nicer than others.

Some materials are considered repulsive, especially those “betwixt and between” known categories. The anthropologist Mary Douglas details these, such as those connected with the abominations of Leviticus. 1 For example, a cow is an “ideal type”, because it walks on four legs and many of us are happy to eat beef. Animals using an unauthorised method of propulsion are not. One such is the worm, which “swarms” and belongs to the realm of the grave, death and chaos. However, what is authorised varies across cultures.

The relevance of this for pharmacists is that many of their medicines are peculiar in being different to the usual food and drink swallowed. Medicines possess unnatural colours, textures, ingredients and volumes; an extreme example is polio vaccine containing living virus, known to multiply enormously in the stomach. Medicines may also have unpleasant side effects such as inducing emesis. However, there is confidence that pharmacists’ medicines are safe; their supply is legitimised by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (one of the functions of a professional body is to reduce uncertainty). 2 So generally, no matter how strange or unpleasant the substances offered by pharmacists appear, those substances are swallowed (whereas in other contexts, they would be spat out). There is some cultural variability in the degree of caution exercised: for example, the Allioch of West Africa swallow food without mastication. Swallowing — passage beyond the mouth — demonstrates real trust, because by then, it is too late for individuals to change their minds. Indeed, note the special category of buccal tablets, the active ingredients of which are absorbed through the lining of the judgement chamber itself, while the “mouth exit system” remains shut. No wonder buccal tablets require special labels and counselling. That trust, to ingest strange substances, is in pharmacists and the medical mainstream in which they are enmeshed. Indeed, some patients may welcome unpleasant tasting medicines, as one pharmacist interviewee volunteered: “Talking about the bitter pill . . . people often . . . say, well, what does this medicine taste like? . . . If it doesn’t taste so nice, maybe they won’t take it, but then they may add this with a sort of, drawn breath, well, the nastier it is, the better”

Similarly, the industrial pharmacists Helliwell and Jones4 argue for not losing the intrinsic medicines’ taste by excessive masking with palatability enhancing chemicals. However, another pharmacist5 notes that sugarless antibiotic mixtures are so unpalatable (“that revolting slime”) that children will not swallow the medicine and parents give up administering it before the courses are finished. Sweetening does make it easier to cope with retaining an unusual material in the mouth. We are conditioned to expect,

and routinely to receive from pharmacists, sweet things.

I first realised that after reflecting upon a particular field note. A drug addict, having verbalised anxiety about tooth decay caused by their methadone mixture, received a sugar-free brand. However, it had been formulated with an artificial sweetener. We ingest

sweet things because they give us an internal feeling of pleasure.

Another field note recorded the sale of sweets from pharmacies: “Kit Kat in hand of customer. I assumed that it was from another shop, but it was not. All the Easte eggs and other sweeties had gone by the end of the day. Sweets were on the counter where children could see, tugging at their mothers.”

Since recorded history began, (wo)men have ingested sweet materials because they gave pleasant, internal feelings. In England, only the aristocratic gourmets ate sweet-meats, which apothecaries made from sugar; the common people had to make do with honey.6 In the past century, popular fiction (Mary Poppins) observed that “a spoonful of sugar makes the medicine go down”, while, today, a dose of polio vaccine, for example, is still swallowed on a lump of sugar.

A founding father of sociology, Emile Durkheim (1858–1917), suggested that you imagine you were a despot of irresistible power. Even if I were such a despot, I could not resist my own desires, 7 such as a desire for sweet things. My desires would be the master of me, just as other people’s desires are masters of them. Despite the physiological, neurological and psychological complexity of my body, when I see a sugar bowl, and put sugar into my tea, a command seems to be given and obeyed within a fraction of a second, entirely internally, without my being conscious of ever having been so taught. Wanting sweet things is an example of bodily desire with origins long before language, as in the words of the contemporary poet/singer Leonard Cohen, “I can’t forget, but I don’t remember what”.8

This can be broadly translated into more natural scientific language. Humans are mammals. One defining characteristic of mammals is that their young suckle milk from lactating mothers; during that process infants ingest sugar. Furthermore, the fundamental, biochemical processes within every cell in every human body require sugar for life processes (and, perhaps, the associated consciousness) to occur. At root, our “sweet tooth” appears to be a “fate”; it is “hard-wired” into our very existence and survival. The poetry and the science share a message so profound that only part can be communicated

by words.

The judgement chamber of the mouth, which accepts wholesome, but rejects poisonous, material is then, of fundamental importance. Predictably, individuals are careful about what they allow into their mouths; only certain groups possess a social mandate to intervene within the oral cavity. In particular, dentists are trusted to invade using eyes, words, fingers, records, needles and scalpels; dentists may even add or amputate oral components. Nettleton offers a sociology of dentistry. 9 Pharmacists are trusted to make dentists’ anaesthetic injections. Pharmacists’ medicines may numb mouths and degrade their ability to judge; amethocaine lollipops are an extreme example.

Pharmacists expect patients to use their mouths in unusual fashions, the gargle being a noisy example. Seldom does any material remain within the judgement chamber for hours but pharmacists may advise patients to do precisely that; witness triamcinolone acetonide 0.1 per cent in an adhesive base, clinging, limpet-like, over mouth ulcers. Even more extreme is when the patient is advised not to swallow a substance but to move the epiglottal flap in order to inhale material into the lungs. This helps us to understand why pharmacists spend so long counselling patients suffering from asthma, and undertake so

much pharmacy practice research on such counselling.

Turning now to the exit from the body, in Great Britain material is seldom inserted past the anal sphincter. Few social groups are mandated to intervene there, nurses administering colonic irrigations being a well-known exception. Pharmacists possess an armament including enemas and suppositories and routinely advise on their use. This encompasses materials to ease discomfort associated with the opening and closing of the rectal sphinc-

ter. There is no equivalent anatomical judgement chamber at the body’s exit, to that at its entrance, which may explain why individuals are even more careful about inserting objects into their rectums than into their mouths.

The body incorporates (ingests) material from and “excorporates” (excretes) material into the world surrounding the body. Generally, at the body’s entrance (lips), incorporation occurs. However, unwanted “excorporation”, such as emesis, may also occur there; pharmacists are specialist healers trusted to provide material (for incorporation) to avoid that undesired “excorporation”. One such is the anti-emetic prochlorperazine maleate tablets.

Generally, at the body’s exit (anal sphincter), “excorporation” occurs and pharmacists are trusted to modify the rate with laxatives or constipating agents. However, occasionally, as already mentioned, incorporation may be required and pharmacists and other healers are mandated to facilitate it. The frequency of such intervention is culturally specific: French, compared with British, patients insert suppositories more frequently.

Generally, ministering to the front, compared with the back, of the body is perceived as more dignified and suitable for public display, altogether in better taste. We dine communally but retire to defecate; while dining, swallowing a medicine is socially tolerated but inserting a suppository is taboo.

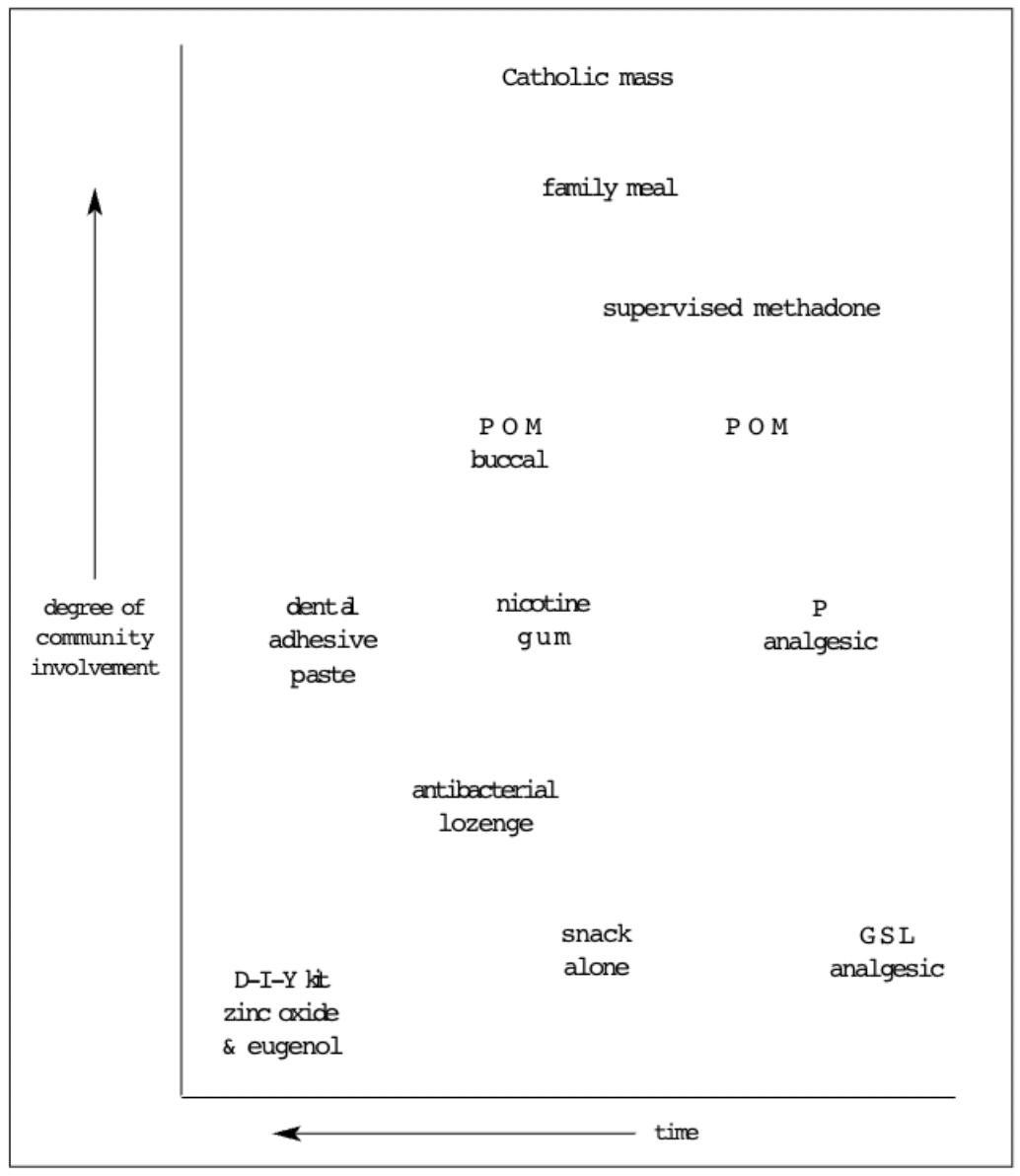

Returning to the front of the body, it is possible to view the culture of incorporation in a wider context, as Figure 1 illustrates, this is developed from a diagram offered by the sociologist/philosopher Pasi Falk.8 The word “community” occurs in Figure 1, as it does in the contemporary, preferred title of the largest sector of British pharmacists (“community” pharmacist), suggesting that the Figure is pertinent for that group.

Figure 1: Incorporation and community

At the top is the Catholic mass. During the ritual which lasts about an hour, the sacraments (bread and wine) are perceived by the assembled believers as transmogrified into something of intense spiritual significance, aided by the powerful pleading of a specialist professional (priest); those sacraments are then incorporated into individual bodies. Pharmacists’ nearest activity to that is, perhaps, the supervision of the swallowing of methadone. This is an activity that has demanded legitimation by a medical practitioner, dispensing, special recording, police oversight and supervision by a pharmacist to witness that incorporation has indeed occurred. Sometimes, other patients also observe, often staring (in surprise) at the addict.

Community involvement decreases from ingestion of a POM, which demands attention from the practitioner and pharmacist, to a P medicine which demands attention only from the pharmacist, to a GSL medicine, which is sold as part of a superstore trolley load. At that point individuals are encouraged to believe — by the geography of the shop floor — that they require no expert assistance whatsoever.

(Ironically, a do-it-yourself, temporary dental repair kit, containing the medicaments zinc oxide and eugenol, is legally not a medicine, despite its lengthy stay within the judgement chamber.)

Within Figure 1, interrelationships are approximate; the figure is designed to demonstrate that bodies function within wider social contexts. Pharmacists play many different roles within those contexts to ensure that medicines — of all types — are ingested.

References

- Douglas M. Purity and danger: an analysis of the concepts of pollution and taboo. London: Ark; 1984.

- Douglas M. How institutions think. London: Routledge Paul; 1987.

- Nomen proprium. Pharm J 1993;251:525.

- Helliwell K, Jones B. How good should a medicine taste? Pharm J 1994;253:181.

- Baldock S. Spoonful of sugar. Pharm J 1998;260:120.

- Wootton AC. Chronicles of pharmacy Part II. London: Macmillan; 1910.

- Nisbet RA. The sociological tradition. London: Heinemann; 1972. p154.

- Falk P. The consuming body. London: Sage Publications; 1994.

- Nettleton S. Power, Pain and dentistry. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1992.