This content was published in 2008. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

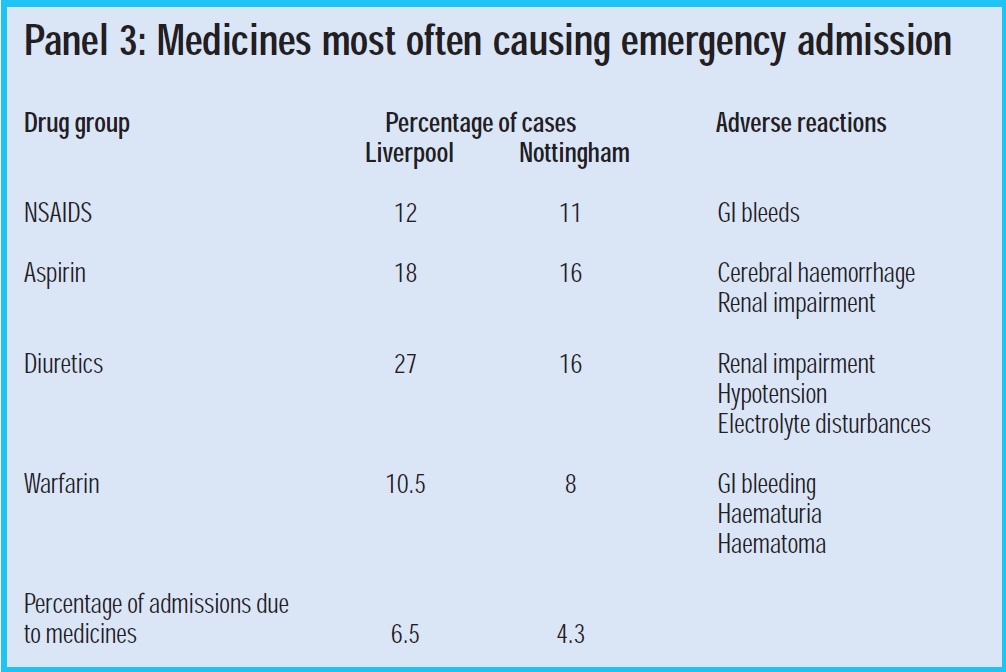

Reducing avoidable hospital admissions is a priority for the NHS.1 Medicines account for about 4–6.5 per cent of emergency admissions,2, 3 and causes related to medicines fall into three broad categories: adverse drug reactions, prescribing errors and poor compliance.2

In theory it should be possible to reduce the underpinning causes for these three types of problems, but evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) suggests that pharmacist medication reviews do not reduce ad-missions.4 However, most studies have not been designed to show a reduction in admissions or even to log this outcome. For instance, they have not focused on the most at-risk group of patients,5 were not well designed — the pharmacists had no access to clinical records,6 and admissions occurred, but a medicines cause was not demonstrated.7

A retrospective review of hospital admissions from one large UK RCT showed that of 77 admissions (from 332 elderly patients recruited to the study) only 17 (22 per cent) were related to pharmaceutical care issues and only 10 (13 per cent) were preventable by pharmacist intervention.8 In the absence of a specific focus on unplanned admissions as an outcome measure, it could be that the results merely show that emergency hospital admission records are not sufficiently sensitive to show the benefits of pharmacist medication reviews. The belief persists that carefully targeted medication reviews do benefit some patients, despite the lack of supporting evidence in unplanned hospital admission records. Medication reviews reduce harm, improve people’s confidence about their medicines and help to improve long-term outcomes.

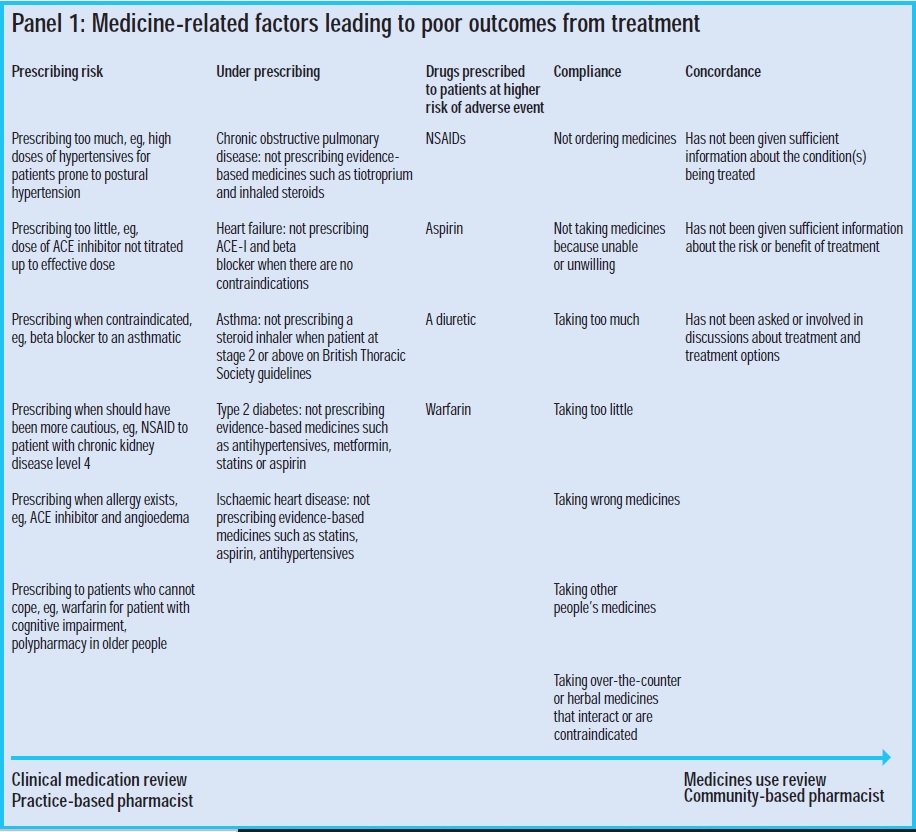

This review will focus on the factors related to monitoring and taking medicines where medication reviews might improve outcomes. In Panel 1 factors that contribute to poor patient medicines-related outcomes are assigned to five categories. Pharmacist medication reviews can affect all of them. Clinical medication review is the best method for assessing prescribing risk, underprescribing and high-risk drug use since it includes access to the clinical record.9 A pharmacist conducting a clinical medication review can cover all five categories. Medicines use review (MUR) is likely to be best for assessing compliance and improving medicines-taking through a concordance approach, although careful patient questioning could also identify some aspects of prescribing risk.

Together these reviews offer a practical method for practice-based pharmacists to work closely with community pharmacists. Once treatment is optimised from the clinical viewpoint the patient can be referred to the community pharmacist for ongoing support with medicines taking and compliance through MUR. Community pharmacists conducting MURs can refer patients to practice-based pharmacists to help implement solutions such as reducing the number of prescribed medicines and changing dosage formulations.

Reducing prescribing risk

One third of medicines-related hospital admissions are due to prescribing errors.2 These include blatant errors — wrong medicine prescribed or prescribing a medicine for which an allergy exists — and more subtle errors, such as failure to stop a medicine after a fixed course of treatment.

Prescribing risk increases when a patient’s physiology is less able to handle prescribed medicines, such as with an older person with reduced renal function who is receiving non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), in precipitating renal failure, or where a patient with hypertension has episodes of postural hypotension as a result of antihypertensive medicines. Close and frequent monitoring is necessary to avoid such problems. This means working with practice and district nurses, and GPs.

Under-prescribing

The most common long-term conditions associated with emergency admission are exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and heart failure.10 There is good evidence that exacerbations can be reduced by medicines. For instance, the optimal treatment of heart failure is a triple regimen of a loop diuretic, an ACE inhibitor and a betablocker,11 yet only 30 per cent of people with a heart failure diagnosis are prescribed a betablocker.12,13 For every 100 people treated with a beta blocker, four hospital admissions and three deaths could be avoided in the first year of treatment.14 Inhaled steroids, prescribed to COPD patients with a forced expiratory volume of less than 50 per cent and two ex-acerbations in the past year, are beneficial in preventing further exacerbations.15 Long-acting beta-agonists and anticholinergics can also prevent exacerbations.16 Optimal prescribing can prevent deterioration of asthma, type 2 diabetes and ischaemic heart disease, but benefits may not be realised for several years.

High-risk drugs

NSAIDs, aspirin, diuretics and warfarin account for half to two-thirds of the 4–6.5 percent of admissions associated with medicines.2,3 Pharmacists can reduce the risk from these medicines by ensuring they are only prescribed where necessary and reviewed regularly, particularly in high-risk patients.

Compliance and concordance

Compliance (or adherence) has been defined as “the extent to which a person’s behaviour matches the prescriber’s recommendations” and should not be confused with “concordance”.17 Concordance is a two-way consultation process. It involves shared decision making about medicines between a healthcare professional and a patient, based on partnership, where the patient’s expertise and beliefs are valued.19

Non-compliance can occur where patients are unable to obtain a supply of medicines, take too little or too much, or take the wrong medicine. All can result in treatment failure and hospital admission. Community pharmacists, in particular, should identify which patients are prone to non-compliance and why. A systematic approach using questions to cover the range of potential non-compliance causes can be used. I use a tool developed for a research project (copy available on request).

Identifying the cause of non-compliance needs to be followed up with solutions that are acceptable to patient and GP. MUR forms state what solutions the pharmacists would like the GP to implement and should be followed up to ensure it was implemented and has improved things for the patient.

Concordance for pharmacists means establishing a relationship with the patient that allows for honest discussions about the condition, treatment options and what the patients wants. Concordance is a style of consultation and pharmacists might need training to develop it.19 Exploring the patient’s health beliefs and wishes is essential if people are to accept what has been prescribed.

Targeted reviews and interventions

How can pharmacists reduce the risk of emergency admission? They could aim reviews at patients who have had one or more recent emergency admissions. This is a logical starting point, but case managers and others may be serving these groups well already. Pharmacists need to work with case managers and GPs to support these patients, but there are other predictors for emergency admission that pharmacists could identify. Should they do so they could reduce risk before admission for the first time. They could, for example, target reviews at patient characteristics, medicine-taking risk factors, high-risk medicines and under-treated conditions.

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics such as reduced renal function, being elderly and having multiple co-morbidities contribute to poor drug handling and increased sensitivity to drugs and likelihood of adverse drug reactions. The elderly are more prone to the effects of benzodiazepines because they have increased gait (swaying) and drugs exaggerate this effect, which can lead to falls.20 Social situations are important, such as living alone and being housebound.21 Patients who are socially isolated and less able to seek help from their GP might gradually worsen until admission is needed. We need to be proactive in identifying and helping these people.

Medicine-taking risk factors

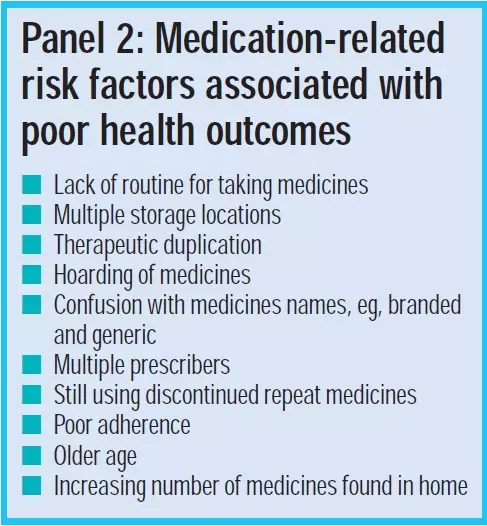

The patient factors and behaviours listed in Panel 2 are associated with poor health out-comes. Some can be identified from the clinical record, such as multiple prescribers and older age. But a face-to-face interaction with the patient at home is usually needed to identify others. This allows the pharmacist to see how the patient manages their medicines. Have they got hoards of unused supplies? Do they have medicines all over the home and do they have discarded medicines in the home? One limitation of an MUR and a review in the GP surgery is that patients bring a sample of what they want you to see or what they can carry.

Compliance

Poor compliance is a risk. A Cochrane review on interventions to improve compliance identified surprisingly little published evidence on what works best.22 Perhaps the three simplest interventions are to reduce the number of medicines prescribed, to reduce the number of daily dosage intervals to once or twice daily, and to ensure that there is regular contact with a health care professional to monitor the condition and to encourage medicine taking.

Medicines and falls

A medicines review should be a part of a falls assessment. Medication review of care home residents by pharmacists reduces falls significantly.23 Increasing numbers of medicines are associated with falls. Sedatives, such as benzodiazepines and drugs causing hypotension should be considered as potential causes.20 A check for postural hypotension should be made because antihypertensives can exaggerate the lowering of blood pressure on standing and that can result in a fall. To screen forth is risk factor, blood pressure should be measured when the patient is lying down and standing up. A drop of systolic blood pressure of greater than 20mmHg or a drop of diastolic blood pressure of greater than 10mmHgare risk factors. Even when “correct” doses of medicines are prescribed the review should identify what is actually being taken; a patient may take too much of a prescribed dose or take another person’s medicine.

High-risk medicines

A small number of medicines are associated with the highest number of emergency admissions attributable to medicines. By considering these medicines in conjunction with patient-related risk factors such as increased age and poor social situation the risk of prescribing a medicine may outweigh the benefits in some instances. Let us consider the four medicines most associated with emergency admissions — NSAIDs, aspirin, diuretics and warfarin — and what can be done to reduce the risk. Panel 3 shows the percentages of emergency admissions and the reason for admission from two large studies in Liverpool and Nottingham. A total of between 4 percent and 6.5 per cent of admissions were due to medicines.

NSAIDs

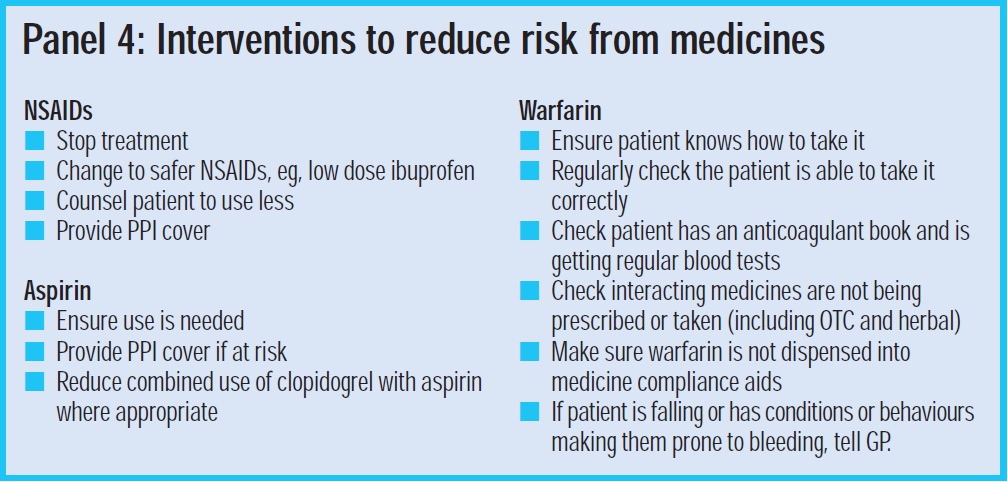

NSAIDs are associated with gastrointestinal bleeds, fluid retention — which can precipitate heart failure — and renal im-pairment.24 The risks are most evident in older people, especially those aged 65 years or older. Panel 4 shows the interventions that can be made. When making recommendations, access is needed to the clinical record (to ensure the medicine is causing the problem) and to the GP, to negotiate any change. As a rule it is best to avoid NSAIDs in older people and to use simple analgesia for conditions such as osteoarthritis. When a NSAID is necessary the advice to patients should be to use the lowest dose possible and to take when required rather than regularly. The use of a proton-pump inhibitor can help to reduce the risk of GI bleeds.25

Aspirin

The first consideration is whether aspirin is indicated, ie, does the patient have established cardiovascular (CV) disease? If aspirin is being used for primary prevention, is the CV risk 20 per cent or more? For patients with a CV risk of greater than 20 per cent, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend treatment with aspirin because the benefits of the drug normally outweigh the risks.26 If aspirin is needed can it be given at the lowest dose, ie, 75mg and PPI cover considered? The risk of a GI bleed can be reduced by stopping concomitant antiplatelet drugs such as clopidogrel, eg, 12 months after combined use after acute coronary syndrome.27

Diuretics

One of the largest risks from diuretics is hyponatraemia and hypokalaemia as a result of failure to monitor urea and electrolytes. Loop diuretics need to be monitored closely to avoid dehydration from too high a dose, or exacerbation of heart failure from too low a dose. Patients with heart failure should receive training on how to recognise symptoms and some may be capable of temporarily altering the dose depending on weight gain or loss caused by fluid.

Warfarin

Warfarin is effective for reducing conditions such as stroke in people with atrial fibrillation, but it is critical to monitor the patient’s lifestyle and ability to comply with the dose. The risks from warfarin can outweigh benefits in an elderly person with cognitive impairment or somebody who is prone to bouts of high alcohol intake. Clinical judgement is needed to assess which individuals are likely to have too great a risk.

Under-treated conditions

Emergency admissions in England in 2003–04 were most often due to COPD (106,517 episodes), angina (79,228), ear, nose and throat infections (72,831), convulsions and epilepsy (64,664), congestive heart failure (62,582) and asthma (61,264).10 Most of the conditions are managed by ensuring patients are treated optimally. Treatment, if taken, should lead to fewer exacerbations and fewer admissions.

Summary

Clinical trial evidence does not show that medication reviews reduce emergency admissions because most studies have not been designed to measure this outcome. Pharmacists working in a community pharmacy and general practice setting could help groups at risk of emergency admissions by reducing prescribing risk, increasing prescribing and helping to improve compliance. Close working with the primary health care team will help achieve success.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Thanks to Dave Alldred for reviewing this paper.

References

- Department of Health. NHS improvement plan. London: The Department, 2004.

- Howard RL, Avery AJ, Howard P, Partridge M. Investigation into the reasons for preventable drug-related admissions to a medical admissions unit: observational study. Quality &Safety in Health Care 2003;12:280–5.

- Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, Green C. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital. BMJ 2004;329:15–9.

- Royal S, Smeaton L, Avery AJ, Hurwitz B, Sheikh A. Interventions in primary care to reduce medication related adverse events and hospital admissions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2006;15:23–31.

- Zermansky AG, Petty DR, Raynor DK, Freemantle N, Vail A, Lowe CJ. Randomised controlled trial of clinical medication review by a pharmacist of elderly patients receiving repeat prescriptions in general practice. BMJ 2001;323:1340–3.

- Holland R, Lenaghan E, Harvey I, Smith R, Shepstone L, Lipp A, et al. Does home based medication review keep older people out of hospital? The HOMER randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2005;330:293.

- Lenaghan E, Holland R, Brooks A. Home-based medication review in a high risk elderly population in primary care —the POLYMED randomised controlled trial. Age and Ageing 2007;36:292–7.

- Krska J, Hansford D, Seymour DG, Farquharson J. Is hospital admission a sufficiently sensitive outcome measure for evaluating medication review services? A descriptive analysis of admissions within a randomised controlled trial. Can pharmacists’ interventions show an impact on hospital admissions? An evaluation of the contribution of pharmaceutical care issues to admission. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2007;15:85–91.

- Lowe CJ, Petty DR, Zermansky AG, Raynor DK. Development of a method for clinical medication review by a pharmacist in general practice. Pharmacy World and Science 2000:22:121–6.

- Institute for Innovation and Improvement. Delivering quality and value. Available at: www.institute.nhs.uk (accessed 1 October 2006).

- National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. Guideline No 5 – chronic heart failure. National clinical guideline for diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2003.

- Study Group of Diagnosis — part of the Working Group on Heart Failure at the European Society of Cardiology. The Euroheart failure survey programme — a survey on the quality of care among patients with heart failure in Europe. Part 2:treatment. European Heart Journal 2003;24:464–74.

- Petty DR, Silcock J, Zermansky AG, Raynor DK. A survey of general practitioners’ perceptions of beta-blocker therapy for heart failure. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2007; Supp2, B29–30.

- Clinical Evidence. Beta blockers for heart failure. Available at: www.clinicalevidence.com (accessed 27 April 2005).

- National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. CG12 —chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Available at: guidance.nice.org.uk/CG12/niceguidance/pdf/English (accessed 28 January 2008).

- Sin DD, McAlister FA, Man SF, Anthonisen NR. Contemporary management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: scientific review. JAMA 2003;290:2301–12.

- Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL. Compliance in healthcare. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1979.

- A competency framework for shared decision-making with patients. Achieving concordance for taking medicines, January 2007. Available at: www.npc.co.uk (accessed 28 January 2008).

- Salter, C., Holland, R., Harvey, I., Henwood, K. (2007). “I haven’t even phoned my doctor yet.” The advice giving role of the pharmacist during consultations for medication review with patients aged 80 or more: qualitative discourse analysis. BMJ 2007;334:1101.

- Leipzig RMCR, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis — psychotropic drugs. Journal of the American Geriatric Society 1999;47:30–9.

- Sorensen HT. Medication management at home: medication-related risk factors associated. with poor health outcomes. Age and Ageing 2005;34:626–32.

- Haynes RB, Yao X, Degani A, Kripalani S, Garg A, McDonald HP. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005.

- 23.Zermansky AG, Alldred DP, Petty DR, Raynor DK, Freemantle N, Eastaugh J, Bowie P. Clinical medication review by a pharmacist of elderly people living in care homes —randomised controlled trial. Age and Ageing 2006;35:586–91.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. In: British National Formulary 52. London: BMJ Publishing Group and RPS Publishing, 2006.

- Rostom A, Dube C, Wells G, Tugwell P, Welch V, Jolicoeur E, et al. Prevention of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal ulcers. Cochrane Database Systematic Review 2006.

- National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. Guideline No 34 — hypertension: management of hypertension in adults in primary care. June 2006.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Technology appraisal 80. Clopidogrel in the treatment of non-ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndrome. July 2004.