Shutterstock.com

Cancer is indiscriminate. It can strike both young and old, rich and poor, and on average, it kills half of those affected within ten years of diagnosis. There are currently 2.5 million people living with cancer in the UK and, by the end of 2016, it is estimated that 1,000 people a day will be told they have the disease. So when it comes to potentially life-extending treatments being denied to these patients, emotions run high and media coverage is extensive. It was against this background that the coalition government created the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) in 2010, set up to ease access to innovative new cancer drugs that have not been approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for use within the NHS in England.

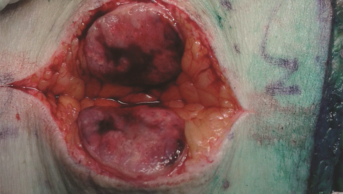

However, demand has far outstripped the original £200m resource. The budget for the CDF was increased to £280m for 2014–2015, and £340m for 2015–2016. Despite this, NHS England estimates that spending will rise to around £410m for this year, an overspend of £70m. To address this overspend, a second round of ‘de-listing’ has been announced, with 17 drugs for 23 indications being removed from the list. This follows the removal of 16 medicines for 25 indications in March 2015. The latest drugs to be removed include big hitters like Roche’s Avastin (bevacizumab) for recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer, advanced breast cancer, and advanced colorectal cancer, and Kadcyla (trastuzumab emtansine), a new targeted therapy for advanced breast cancer.

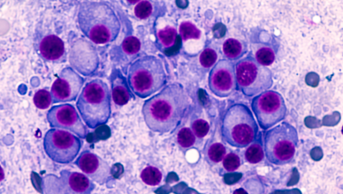

Despite the fund’s flaws — critics point out that it undermines the work of NICE and takes money away from other disease areas — we must not lose sight of the bigger picture. The CDF has enabled an estimated 72,000 people in England to receive innovative drugs that they might otherwise not have been able to access. It has undoubtedly extended and improved lives, some by only a few weeks, but some by much longer. But, more than that, it will encourage innovation. Cancer treatment is undergoing a revolution. Doctors are starting to sequence tumour DNA to help customise treatments, and researchers are developing immunotherapies to harness the power of the body’s own immune system to fight the disease. There is a buzz about these developments among oncologists, and for patients they give hope of a durable response where previously there was little.

For these innovations to continue to receive the investment they deserve, patients must gain access to these new drugs, and data must be collected on their safety and effectiveness so that incremental improvements can be made. We need a way to provide these desperate patients with innovative medicines now.