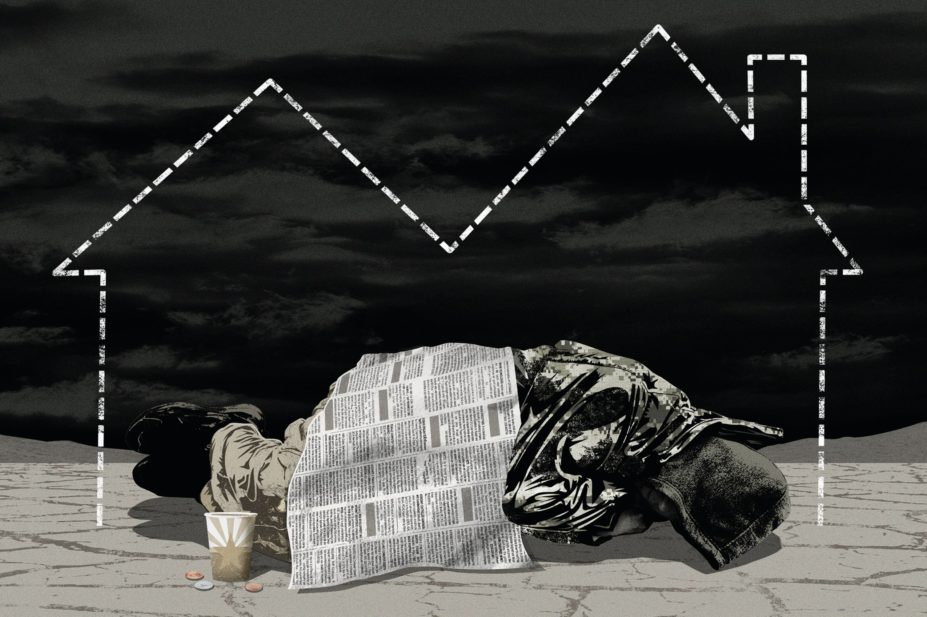

Taylor Callery / Ikon Images

The continuing assault on public sector finances since the last major recession in 2008 has pushed increasing numbers of families a step closer to homelessness. Real income for typical working families is now estimated at approximately 10% down from 2008 levels[1]

. From 2010–2011 to 2015–2016, there has been an estimated 37% real-term reduction in government funding to local authorities[2]

. The cuts in public sector finances are hitting the most vulnerable in society the hardest. The affluent areas, including the likes of London and Brighton, have seen the highest rates of rise in the numbers of rough sleepers. Nearly twice as many people sleep rough on any given night now in England than in 2010[3]

,[4]

. The numbers of hidden homeless, including sofa surfers and those living with relatives, are often missed in the official statistics.

Lack of focus on non-housing issues

Resolving the housing issue takes the priority at the policy level when it comes to managing homelessness, and rightly so.

Local authorities admit that it could take several years to house the people who are currently homeless

However, local authorities admit that it could take several years to house the people who are currently homeless because there is a lack of adequate council housing to match the demand from the growing numbers seeking their assistance. The continued funding squeeze also means that non-housing issues faced by the homeless get neglected. These include lack of tailored primary healthcare services[5]

, counselling[6]

, self-care support[7]

and provision of healthy diet in the community[8]

. These services are effective in alleviating the impact of homelessness while people are waiting to be rehoused.

Need for integrated services

Homeless patients are repeat attenders of hospital accident and emergency (A&E) departments. It is estimated that the homeless constitute approximately 8% of all repeat users of the service[9]

. Repeat attendance is mainly linked to their poor general health and lifestyle. However, these are exacerbated by a lack of joined-up services in the community. There is a strong link between substance misuse, mental illness, violent family relationships and homelessness with co-morbidities highly prevalent in this population[10]

. This means integrated services are most relevant to this population.

Current arrangements are not keeping pharmacists in the loop about wider social care support for the homeless

The opioid substitution service provides a relevant example and an important opportunity to further integrate pharmacy services to the mainstream primary health and social care. Up to 50% of patients facing a repeat cycle of homelessness receive methadone services through pharmacy[11]

. Many patients are on a repeat dispensing schedule that allows pharmacists to provide opportunistic advice and intervention. This may include provision of interventions for alcohol misuse or referral to social care services. However, pharmacists are often limited by lack of access to information about patient co-morbidities. Patients — for their rights of confidentiality, access and choice of healthcare services — can choose to use any pharmacy to obtain their prescribed treatments. This may lead to a lack of opportunity for pharmacists to have a holistic view of the patient. Current arrangements are not keeping pharmacists in the loop about the wider social care support available to the homeless population.

Medicines management is another area where integrated services are urgently needed. Lack of stable housing has led to patients often storing their medicines in their pockets and taking them wherever they go. Theft of medicines is a common problem[12]

. Current social care provisions are not adequate in helping them achieve best outcomes from the medicines that require special arrangements, such as those requiring refrigeration for storage. Only a few local authorities have been able to formalise medicines management plans for those living in council temporary accommodations. For example, a multi-disciplinary approach to medicines management allowing a nominated social care professional to collect prescriptions on behalf of homeless patients has been formulated through collaborative shared agreements between multiple stakeholders in some local authorities[13]

. However, lack of adequate funding means there are no guarantees for such innovative services to be continued or expanded to the rest of the country.

Contrary to what appears in written policy, homeless patients are often denied registration and access to primary care

Access to primary care is itself an issue for the homeless patients. Contrary to what appears in the written policy[14]

, homeless patients are often denied registration and access to primary care, including their general practitioners, mainly because they lack a ‘fixed abode’. The provision of ‘my access to healthcare’ card — designed to help people who are homeless to register and receive treatment at London general practices — illustrates this situation. Primary healthcare centres for the homeless have been established across the UK to alleviate the problem and to provide specialist services for these vulnerable patients. Patients are highly satisfied with these specialist services. A recent study in Aberdeen demonstrated that homeless patients regard clinical staff’s interpersonal skills highly as well as knowledge of homeless patients’ clinical conditions in the context of their wider social circumstances[15]

. Some of these specialist healthcare centres also offer dentistry, podiatry, substance misuse and psychotherapy counselling services all within one premise. However, the high level of patient satisfaction has also led to reluctance among some patients to relocate to the mainstream healthcare services once patients are rehoused. Such reluctance is also down to patient perception that the rest of the primary care services are not best placed to provide tailored services for their specialised needs[15]

.

Reports of homeless patients with severe mental health problems being discharged to the streets have come to light

Discharge planning protocols of hospitals in England requiring hospitals to make sure that a patient has a place to go and live before they are discharged is a good example of attempts to integrate services[16]

,[17]

. However, lack of adequate funding in the community has often confined this to the papers. Recently, reports of homeless patients with severe mental health problems being discharged to the streets have come to light[18]

.

Funding squeeze will impact on innovation

There are no guarantees that the health and social care funding situation is going to get better any sooner. Cutting community pharmacy funding puts provision of extended-hour services at risk, further limiting the time pharmacists can focus on the vulnerable patients. Additional care of these vulnerable patients is not possible without adequate remuneration for the services. Lack of resources will prohibit the design, piloting and commissioning of innovative services. There is a need to redesign and invent services around mental health, substance misuse and injury management in this vulnerable population. Unfortunately at the moment, the success is about maintaining the current level of services available to this population.

Patient outcomes-based research

Operating in a constrained environment requires that services that can deliver positive patient outcomes are sustained. Services commissioned without rigorous evidence of benefits on patient outcomes do not lend to cost-effective utilisation of resources. Outcome assessment in service evaluation and research should focus on their sustainability, and not just the transient impact. For example, the long-term impact of pharmacist-led medication review is beginning to emerge over time[19]

.

Questions have been raised about the impact on patient outcomes from one-off medication reviews conducted without follow-up care

Questions have been raised about the impact on patient outcomes from one-off medication reviews conducted without follow-up care[20]

. Lack of sustainable outcomes may require services to be abolished or redesigned, including any funding arrangements. Outcome-based payments for pharmacy services, as we have seen with smoking cessation services, require that follow-up efforts are appropriately remunerated.

Time to look at the curriculum

Clinical educators are important partners in thinking about the future. For example, a few pharmacists will recall having covered in depth the aspects of the vulnerable population, especially the homeless, in our pharmacy degrees. So their care comes as a surprise to many newly qualified pharmacists. This may limit their ability to build a meaningful empathy in their effort to help this population. Homelessness is becoming a more visible problem in the society, and our curriculum should reflect this emergence. An inward view from a purely medical perspective will not be adequate to address the wider issues these patients face in day-to-day practice.

Addressing a growing problem

Homelessness is a growing problem and is demanding joined-up working across sectors including primary healthcare, social care and academia. Policies and funding commitments have not gone far enough to protect the most vulnerable in the society. Healthcare professionals, including pharmacists, need the commitment that extra funding will secure and improve the valuable services that they provide.

Vibhu Paudyal is a senior lecturer of pharmacy at the University of Birmingham. He is an active researcher in the area of access to medicines, self-care and use of healthcare among diverse populations including the homeless, offshore workers and pharmacy clientele.

References

[1] The London School of Economics and Political Science. Real wages and living standards: the latest UK evidence. Available at: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/real-wages-and-living-standards-the-latest-uk-evidence/ (accessed June 2017)

[2] National Audit Office. Local government report by the comptroller and the auditor general. Available at: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Impact-of-funding-reductions-on-local-authorities.pdf (accessed June 2017)

[3] Homelessness link. Rough sleeping — our analysis. Available at: http://www.homeless.org.uk/facts/homelessness-in-numbers/rough-sleeping/rough-sleeping-our-analysis (accessed June 2017)

[4] GOV.UK. Homelessness statistics: Statutory homelessness in England. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/homelessness-statistics (accessed June 2017)

[5] Elwell-Sutton T, Fok J, Albanese F et al. Factors associated with access to care and healthcare utilization in the homeless population of England. J Public Health 2016 Feb 18:fdw008. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdw008

[6] Chaturvedi S. Accessing psychological therapies: homeless young people’s views on barriers and facilitators. Counselling Psychother Res 2016 Mar 1;16(1):54–63. doi: 10.1002/capr.12058

[7] Paudyal V, MacLure K, MacKenzie M et al. Self care amongst the homeless a qualitative study. Int J Pharm Pract 2016 24:S3:40–41.

[8] Seale, JV, Fallaize R & Lovegrove A. Nutrition and the homeless: the underestimated challenge. Nutr Res Rev 2016 (June): 1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0954422416000068

[9] Lynch RM, Greaves I. Regular attenders to the accident and emergency department. Emerg Med J 2000;17:351–354. doi: 10.1136/emj.17.5.351

[10] Hwang SW, Tolomiczenko G, Kouyoumdjian FG et al. Interventions to improve the health of the homeless: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2005:29:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.017

[11] Paudyal V, Kamarudinb MAB, Stewart D et al. General practice prescribing of medicines for homeless patients in Aberdeen: analysis of trends using PRISMS database. Int J Pharm Pract 2016:24(S1):28–29. Available at: https://insights.ovid.com/international-pharmacy-practice/injpp/2016/04/001/general-practice-prescribing-medicines-homeless/36/01445440

[12] Paudyal V, MacLure K, Buchanan C et al. When you are homeless, you are not thinking about your medication, but your food, shelter or heat for the night’: behavioural determinants of the homeless population adherence to prescribed medicines. Pub Health 2017 (epub ahead of print). doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.03.002

[13] Safe Newcastle (Newcastle City Council). Drug Management Protocol Newcastle Temporary Accommodation. Available at: https://www.newcastle.gov.uk/wwwfileroot/legacy/nhf/Protocolrev09.pdf (accessed June 2017)

[14] NHS England. Patient registration. Standard operating principles for primary medical care (general practice). Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/11/pat-reg-sop-pmc-gp.pdf (accessed June 2017)

[15] Paudyal V, Gibson Smith K, Maclure K et al. Relocating and integrating formerly homeless patients from a homelessness healthcare centre to mainstream primary care services: perspectives of patients and healthcare staff. Faculty of Public Health Conference, October 2016, Dunblane, UK.

[16] Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. Homelessness and health information Sheet number 4 hospital discharge. Available at: http://www.nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/137857.pdf (accessed June 2017)

[17] London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Available: homelessness prevention and hospital discharge protocol. Available at: http://www.richmond.gov.uk/mental_health_hospital_discharge_protocol.pdf (accessed June 2017)

[18] BBC News. Mentally-ill homeless discharged back to street. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-37249818 (accessed June 2017)

[19] Hatah E, Bround R, Tordoff J et al. A systematic review and metaâ€analysis of pharmacistâ€led feeâ€forâ€services medication review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;77:102–115. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12140

[20] Huiskes VB, Burger DM, Van Den Ende CHM et al. Effectiveness of medication review: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Fam Pract 2017;18:5. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0577-x