Abstract

Aim

To explore GPs’ perceptions of community pharmacist-conducted medicines use reviews (MURs).

Design

Self-administered questionnaire.

Subjects and setting

GP practice prescribing leads who attended three locality meetings held by Cornwall & Isles of Scilly Primary Care Trust prescribing team.

Results

Fifty-two (90%) of 58 GPs completed the questionnaire. Nearly two-thirds of the doctors claimed to have a good working relationship with their local community pharmacist. Half of the respondents consulted with the community pharmacist on drug-related issues at least once a month. However, GPs in general expressed negative views about MURs.

Conclusion

There is a positive foundation as regards working relationships between community pharmacists and GPs, but the GPs identified a number of aspects of the MUR service that they considered needed revision and improvement.

Medicines use reviews (MURs), introduced into the new community pharmacy contract as an advanced service in April 2005, are intended to be structured, concordance-centred reviews with patients receiving medicines for long-term conditions to establish a picture of their use of the medicines — both prescribed and non-prescribed.1 Evaluation of the MUR service2,3 has identified the training and development needs of pharmacists,4 the attitudes of pharmacists towards the MUR service,5 and barriers and facilitators to MURs.6,7

Identified barriers to performing MURs include a lack of marketing of potential benefits to patients and GPs, and the perception that the public may be concerned that MURs may encroach on the responsibilities of GPs.8 Other GP-related barriers include variability in the level of awareness of MURs among GPs, the format in which the MUR information is provided to GPs,9 GPs’ perception of commercial versus professional drivers for the pharmacist, and GPs’ uncertainty of the value of MURs to patient care.10

As a supplement to a wider study into MUR outcomes regarding prescribed medication and pharmacists’ views and attitudes towards MURs, we opportunistically surveyed a small sample of GPs located within Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Primary Care Trust to explore their perceptions of MURs. The PCT has a population of about 500,000 and has 70 GP practices (323 partners) and 88 community pharmacies. At the time of this survey, 57 pharmacies were undertaking MURs and 5,398 MURs had been conducted between April 2006 and March 2007.

Method

We developed a self-administered questionnaire based on relevant published research into MURs and local knowledge of MUR service development. The questionnaire explored GPs’ working relationship with local community pharmacists, frequency of consultation with their local community pharmacist regarding a drug-related query, level of awareness of MURs and experience of receiving them, perception of pharmacists’ ability to conduct MURs and, if applicable, how MUR advice received from pharmacists was managed. There was also a section for free text inviting comments on how MURs were perceived by the wider GP practice, what the responding GP considered a useful MUR and what they considered a waste of their time, and finally how the MUR process could be improved.

The questionnaire was distributed to GPs attending one of three locality-based prescribing meetings held in March and April 2007. These meetings, organised by the PCT prescribing team, are held about five times a year and have a focus on clinical and medicines management issues. Each GP practice is asked to nominate a GP prescribing lead to attend these meetings and report back to the practice. At each of the three locality meetings the GPs were advised that there was some local ongoing research into MURs and that completion of the questionnaire would feed into that research. GPs were asked to complete the questionnaire during the tea break having been advised that it was anonymous and would take only a few minutes to complete.

Data were managed and described using SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc) and free text comments were tallied and grouped into major themes.

Results

The three meetings were attended by a total of 58 GPs, and completed questionnaires were returned from 52 (90 per cent). No GP characteristics were recorded although it is known that approximately 80 per cent were male and approximately half of the GPs belonged to a dispensing practice, although all the dispensing practices represented would also have had non-dispensing patients.

When asked which statement best described their working relationship with their local community pharmacist, 31 (60 per cent) responded that the relationship was good, 14 (27 per cent) said it was limited, two (4 per cent) said it was poor and five (10 per cent) reported they had no working relationship. Twelve GPs (23 per cent) reported consulting their local community pharmacist about drug-related issues frequently (more than four times a month), 14 (27 per cent) occasionally (one to four times a month), 19 (37 per cent) rarely (once or less a month) and seven (13 per cent) never.

In relation to the MUR service, 50 GPs (96 per cent) were aware of the service. Twenty-nine GPs (56 per cent) of all the 52 respondents had received 10 or more MUR forms, 17 (33 per cent) had received fewer than 10 forms, and six (12 per cent) had received no forms.

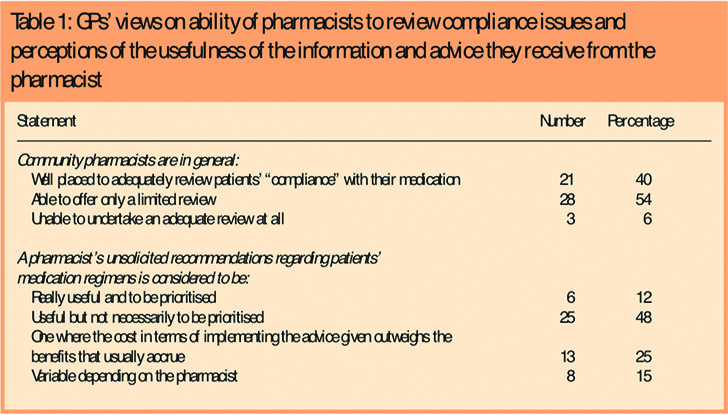

Table 1 describes the views of GPs on the ability of pharmacists to review compliance issues and GPs’ perceptions of the usefulness of the information and advice they receive from the pharmacist.

Thirty-one (60 per cent) of the GPs reported that they thought the pharmacists’ recommendations were generally useful though only one-fifth of these respondents considered the recommendations to be a priority.

In free text response to the question about how the GP thought their practice partners perceive the usefulness of MURs, there were 23 explicitly negative responses, seven hinting at some positive view of MURs and five that were explicitly positive (Panel 1).

Panel 1: Examples of responses to the question “How do your GP partners perceive the usefulness of MURs?”

Positive

- Useful

- Generally helpful

- All partners act on them

Slightly positive

- Of mixed value

- Have very limited value

- Of marginal benefit

Negative

- Poor

- Of no benefit

- Apaperexercise

- MURs are useless and the service is overpaid

- MUR stands for Medically Useless Review

Examples of responses to the two questions that asked the GP what would constitute a really useful MUR, and what they would regard as a waste of their time are shown in Panel 2.

Panel 2: Examples of GPs’ views of useful and less useful MURs

What would constitute a really useful MUR?

- Having a single sheet of paper with brief relevant action points

- The importance of having a closer working relationship with the practice

- Receiving information on patients who have compliance problems or where there are issues with adverse effects or interactions

- The pharmacist ensuring that patients understand more about their medicines

- Targeting of MURs to particular groups of patients (eg, those on polypharmacy or complex regimens, those who do not attend surgery for follow up, and conducting domiciliary MURs)

What would constitute an MUR that you regard as a waste of your time?

- Pages of information and having to hunt for (unhelpful) advice

- Asking the GP to check BPs etc when these reviews have already been done

- MURs conducted on patients who have been on the same treatment for years and the GP knows they arecompliant

- When the practice has recently conducted a medication review

- One that highlights known problems that the GP is working on or has solved to their best ability

- Discussing adverse effects that are inevitable and which the GP will have balanced against the clinicalneed for the drug

When asked to suggest how the MUR process should be improved, respondents identified: technical matters such as simplifying the paperwork and having succinct action points; ensuring that the patient is clear about the MUR process and that it is not a clinical review; pharmacists to comment on compliance issues, the patient’s understanding of their medication and any problems with opening containers; more collaborative working with the practice, emphasising that the pharmacist should not make negative remarks to the patient about the surgery; and targeting specific patient groups for an MUR.

Discussion

We have presented findings on how a self-selecting group of GPs view the MUR service as they and their colleagues experienced it. Nearly two-thirds of the doctors claimed to have a good working relationship with their local community pharmacist, with half of the respondents reporting that they consulted on drug-related issues more at least once a month, though paradoxically GPs in general expressed negative views about MURs.

Although our survey involved a relatively large proportion of GPs from dispensing practices, our findings support previous work identifying barriers to the provision of MURs, albeit from the perspective of stakeholders. A lack of clarity about what constitutes an MUR has been recognised as a barrier2,11 and in our study GPs expressed concerns about MURs that contained advice on clinical matters rather than addressing practical issues in medicines use, or where the GP felt that the patient had been given an incorrect view on the purpose of an MUR. This may be overly critical, however, in that community pharmacists, without access to patient records, may well make recommendations that have already been tried or considered but rejected by the GP. In addition, there may be occasions when it is appropriate for the pharmacist to make purely clinical suggestions.12

The comment that an MUR is regarded as a waste of time when the practice has recently conducted its own medication review may be more a reflection on what the patient can recall of the interaction with the GP at the medication review and what the patient relayed to the community pharmacist, rather than a justified criticism of the pharmacist. Also, negative views on MURs identifying adverse drug reactions that the GP considers inevitable and tolerable perhaps misses the point of the MUR process: such an adverse drug reaction will have been raised with the community pharmacist by the patient and has implications for an approach to treatment based on the concordance rather than the compliance model (the paternalistic “doctor knows best” type of approach).

The view that the MUR process somehow duplicates work already undertaken or considered by the GP may signal issues around professional boundaries and the fact that not all physicians view favourably greater involvement of pharmacists in patient care.13 This may account for comments that MURs conducted in isolation from the practice have limited use and the positive suggestions for closer collaboration and integration between the practice and community pharmacists.14 GP engagement in, and support for community pharmacists conducting MURs is rightly seen as an important determinant to the success of the service and our study confirms this belief.

The complexity of the MUR paperwork9 elicited a large number of free text comments, and this substantiates the national decision to revise the MUR documentation.

Some GPs in our survey must have recognised the potential for benefit from MURs in that 11 of those who added free text, including some with negative views over the present MUR process, suggested priority target groups. Notably disappointing is the fact that some of these target groups (patients recently discharged from hospital, and housebound patients) had already been identified by the PCT and agreed with contractors as priorities for MURs.

Limitations of our study relate to acknowledged concerns with questionnaire surveys and the relatively small number of GPs surveyed. Although free text questions, of which we had four, have their advantages, they also have disadvantages in that they require more thought and time on the part of the respondent. A common problem in questionnaire surveys is the tendency of people to give the perceived desirable answers. Attempts were made to minimise this tendency by emphasising that the data would be processed anonymously and that it would not be possible to link responses to demographic details of the respondent. We cannot investigate therefore if there were differing rates of response between, for example, dispensing and non-dispensing practices or older and younger GPs. However, the fact that many of the views expressed by these GPs have been recorded in other publications strengthens the veracity of our results.

We also recognise the limitations associated with delivering a questionnaire that was brief and hence could be completed quickly (with the aim of achieving a high response rate), as well as gauging the views of GPs who attended meetings held specifically for other purposes and who, in their role of practice prescribing lead, could be described as a self-selected group.

In interpreting this data we are mindful that approximately half of the responding GPs worked in dispensing practices. The relationship between dispensing doctors and local community pharmacists may be associated with a different set of dynamics than that of their non-dispensing colleagues from more urban areas, and dispensing doctors may have a different view of community pharmacy.

In conclusion, our small survey, as well as reinforcing the findings of others, identifies opportunities for further local action to support and embed the MUR service. In particular, it is important to clarify for both GPs and pharmacists the main purpose of an MUR, and to facilitate GPs and pharmacists working together to resolve identified problems, recognising the need for clear, shared expectations of collaboration by both pharmacists and GPs.15

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the 2006 Servier Prescribing and Medicines Management Practice Research Award.

This paper was accepted for publication on 1 October 2007

About the authors

Michael Wilcock, MRPharmS, is head of the prescribing support unit, Cornwall & Isles of Scilly Primary Care Trust.

Geoffrey Harding, PhD, is senior research fellow at Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry, Exeter.

Correspondence to: Michael Wilcock, c/o Pharmacy Department, Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust, Truro, Cornwall TR1 3LJ (e-mail mike.wilcock@ciospct.cornwall. nhs.uk)

References

- Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Available atwww.psnc.org.uk/uploaded_txt/Service%20Spec %20AS1%20-%20Medicines%20Use%20Review-Prescription%20Inter.pdf (accessed 6 July 2007).

- Blenkinsopp A, Celino G, Bond C, Inch J. Medicines use reviews: the first year of a newcommunity pharmacy service. Pharmaceutical Journal 2007;278:218–23.

- Elvey R, Bradley F, Ashcroft DM, Noyce PR. Implementing medication usage reviews through the new community pharmacy contract: key drivers and barriers. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2006;14(Suppl 2):B32.

- Alexander A. MUR — Emerging training and development needs. British PharmaceuticalConference, Manchester, 6 September 2006. Available at www.healthlinks-events-bpc.co.uk/14.45%20Angela_Alexander.pdf (accessed 6 July 2007).

- Latif A, Boardman H. Pharmacists’ attitudes and factors affecting the numbers of medicinesuse reviews (MURs) performed. 13th Health Services Research and Pharmacy Practice Conference, Keele, 2–3 April 2007. Available at www.hsrpp.org.uk/VolAbstracts.pdf (accessed 6 July 2007).

- Hall J, Smith I. Barriers to medicines use reviews: comparing the views of pharmacists and PCTs. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2006;14(Suppl 2):B51.

- Thomas R, John D, Roberts D, James D. Barriers and facilitators to the delivery of medicines use review (MUR) services in community pharmacies in Wales. 13th Health Services Research and Pharmacy Practice Conference, Keele, 2–3 April 2007. Available at www.hsrpp.org.uk/VolAbstracts.pdf (accessed 6 July 2007).

- Doherty L. Medicines use review in primary care and the community. Experience in the field: An independent perspective. British Pharmaceutical Conference, Manchester, 6 September 2006. Available at www.healthlinks-events-bpc.co.uk/15.15%20lee_doherty2. pdf (accessed 6 July 2007).

- Stoate H. Why many GPs ignore MUR forms. Prescribing and Medicines Management 2006;(December):PM1.

- North G. The challenge of MURs. British Pharmaceutical Conference, Manchester, 6 September 2006. Available at www.healthlinks-events-bpc.co.uk/16.00%20 graham_north.pdf (accessed 6 July 2007).

- Kerr C. Medicines use reviews experience in the field: Lloyds pharmacy. British Pharmaceutical Conference, Manchester, 6 September 2006. Available at www.healthlinks-events-bpc.co.uk/15.45%20clare_kerr.pdf (accessed 6 July 2007).

- Jenkins DJ. £25 MUR fee is money well spent. Pharmaceutical Journal 2007;278:551.

- Spencer JA, Edwards C. Pharmacy beyond the dispensary: general practitioners’ views. BMJ 1992;304:1670–2.

- All-Party Pharmacy Group. The future of pharmacy. Report of the APPG inquiry. June 2007. Available at: www.appg.org.uk/ documents/ThefutureofPharmacy_004.pdf (accessed 13 October 2007).

- Chen TF, Crampton M, Krass I, Benrimoj SI. Collaboration between community pharmacists and GPs – impact on interprofessional communication. Journal of Social and Administrative Pharmacy 2001;18:83–90.