Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the quantifiable difference of medicines use reviews (MURs) on GP prescribing for patients who have undergone such a review and to explore community pharmacists’ perceptions of MURs and their impact on patients.

Design

A quantitative analysis of changes to prescribed medication following MURs and a nested qualitative study of pharmacists’ beliefs and expectations of MURs.

Subjects and setting

Twenty-three community pharmacies conducting MURs contributed to the quantitative aspect and 10 pharmacists took part in the qualitative survey.

Outcome measures

Changes in prescribing patterns for patients with coronary heart disease following MURs, and pharmacists’ beliefs and expectations of MURs.

Results

Quantitative analysis indicated that 56 per cent of the pharmacists’ recommendations had been actioned. Advice to review medication was the most common recommendation. Analysis of interviews yielded four themes relating to perceived constraints on pharmacists, their confidence in undertaking MURs, educating patients on medicines use, and impact of MURs on pharmacist/prescriber relations.

Conclusions

The study quantified some beneficial process measures and supports the principle that community pharmacists have a role in reviewing and advising on patients’ medication. But the qualitative study identified constraining issues relating to professional autonomy and training that may inhibit the effectiveness of MURs.

Medicines use reviews (MURs), introduced as part of the advanced service of the new pharmacy contract in England, are structured, concordance-centred reviews with patients receiving medicines for long-term conditions to establish a picture of their use of medicines, both prescribed and non-prescribed.1 Although this service creates an opportunity to explore patients’ experiences with a view to improving their knowledge and use of medicines, little is known about the impact and value of MURs.

Pharmacists’ involvement in the medication review process has been tested in a number of randomised controlled trials. In general these have shown that clinical medication review by pharmacists with specific training and with full access to all relevant information shows some positive findings such as identification and resolution of medication-related problems2 and a reduction in prescribing costs.3,4 However, other studies,5–8 in which pharmacists had access to limited clinical data, have demonstrated that such clinical medication reviews do not seem to translate into measurable benefits to patients or health services, leading to questions over the value of pharmacist-led medication reviews and in particular the MUR service.9–11

Despite being an advanced service of the pharmacy contract, there is little evidence to support their effectiveness and their value for money. Indeed research has identified specific challenges associated with MURs.12,13 These include GPs’ poor reception of the MUR service and paperwork,14.15 the commercial pressure to undertake MURs as perceived by some pharmacists, and the lack of confidence that pharmacists may experience in conducting MURs. In addition, previous work has suggested that patients’ experiences of a more specific type of medication review were not always as positive as they could have been.16,17

We report the findings of a small scale study that aimed to quantify the effect of MURs on GPs’ prescribing and, using a nested qualitative study, explore pharmacists’ perceptions of the impact of MURs on patients, thus allowing us to match a provider perspective of MURs against routinely collected prescribing data. In doing so we aim to establish how pharmacists’ beliefs and expectations relate to GP prescribing practices for a target group of patients with or at risk of coronary heart disease (CHD).

CHD is a national priority.18 The average pharmacy is expected to have 122 people with angina and 24 people each year needing treatment following a heart attack.19 Patients with CHD are potentially at risk of suboptimal adherence to their medicines and may be viewed as a group of patients for whom there are opportunities to discuss and improve concordance issues. These risk factors arise for a number of reasons. Patients may be started on multiple medicines all at once after suffering a myocardial infarction. They may be taking multiple medicines, and/or medicines that require strict dosage instructions (which may affect compliance — eg, nitrates and statins), or patients may have limited understanding of why they are taking their medicines.20

To better understand the impact of MURs on patients with CHD we aimed to quantify the effect on GP prescribing for patients who have undergone such a review. Although we know that GPs have concerns over the MUR service, we know little of pharmacists’ perceptions of this service. Therefore we also explored community pharmacists’ perceptions of MURs and its impact on patients.

It was expected that for patients with CHD any recommendations arising from the MUR process and communicated to the GP would mainly be concerned with improving the ease with which patients are able to take their medicines. We also expected there would be some clinical issues relayed to the GP relating to identification of drug therapy problems.

Method

Quantitative study

The study aimed to recruit about 400 patients with CHD who had received an MUR. When the study started, 42 of the 88 pharmacies in Cornwall and Isles of Scilly PCT were undertaking MURs and about 3,400 MURs had been undertaken be-ween April and December 2006.

All pharmacies in Cornwall were invited to take part in the research. We intended to recruit 20 pharmacies, each contributing about 20 patients. Eligibility for participation required the regular pharmacist and the pharmacy to be accredited to conduct MURs and to have been undertaking MURs for at least three months.

The participating pharmacies were advised that data collection would be conducted by a self-employed locum for both independent and multiples. This individual visited all participating pharmacies to search their MUR records (at least three months old at the time of the search) to identify about 20 patients with a suspected diagnosis of CHD.

Patients were identified as having, or being at risk of, CHD by trigger drugs listed in the MUR documentation. These were low-dose aspirin, clopidogrel, nitrates, cholesterol lowering drugs (statins, fibrates, ezetimibe), or nicorandil. Relevant data — age and gender as well as the medication profile at the time of the MUR — were extracted from the MUR form for these identified patients. In addition, dispensing data from a period about three months after the MUR had been conducted was collected from the PMR for such patients.

Accepting that over three months patients may experience changes to their medication for various reasons, we also collected data on a control group of patients from the same pharmacy at the same time as data were collected for the patients exposed to the MUR (the intervention patients). These control patients were identified by searching prescriptions (index prescriptions) dispensed on the day of the data collection visit (or those dispensed a few days before the visit) containing the same trigger drugs. Relevant data were extracted from the recently dispensed prescription and also from the PMR from a period about three months before the index dispensing.

The data collection tool was piloted in one pharmacy, resulting in minor modifications. Results from this pharmacy were included in the analysis. For both intervention and control patients the first 20 MUR records or prescriptions searched matching the eligibility criteria were included, accepting that pharmacies may store their MUR documentation in different ways (eg, chronologically or alphabetically).

For the quantitative investigation, we evaluated the impact of MURs on patients’ medicines by comparing the recommendations made to the GP with the subsequent pharmacy PMR. Analysis focused on expected outcomes (eg, changes to prescribed medication) as recommended by the MUR compared to any actual recorded changes to medication as noted in the PMR three months after the review. Issues and recommendations in relation to prescribed medication made by the community pharmacist were classified using a modified version of a previously published method.3 The drugs involved in the issues and recommendations were categorised using the British National Formulary.21

A similar, though less detailed, comparison of medication changes was made for the control group of patients. Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, US).

Qualitative study

A purposive sample of 10 community pharmacists spread geographically across urban, semi-urban and rural communities and representing multiple and independent pharmacies was recruited by telephone from the list of pharmacists currently undertaking MURs. Audiotaped telephone interviews (about 30 minutes and conducted by GH) were undertaken. Development of an appropriately relevant topic guide was informed by the aggregated comments and thoughts about MURs received from community pharmacists at a prior meeting organised by the authors to introduce the project.

Data analysis was developed using a framework approach.22 Independent analysis of a selection of the transcripts was undertaken by MW. Comparison of emergent themes from these transcripts was made and a final set of four theme headings agreed upon.

Results

Quantitative study

Recruitment of pharmacies commenced towards the end of 2006 and data

collection ceased at the end of April 2007. In total, 23 pharmacies (55 per cent of those conducting MURs) contributed data allowing 1,948 MURs to be searched. Of these MURs, 1,058 contained one or more of the named trigger drugs but only 294 MURs had any “prescribing” recommendation. Hence 294 intervention patients (those who had undergone an MUR) were available for analysis — a mean of 13 patients (range zero to 21 patients) per pharmacy.

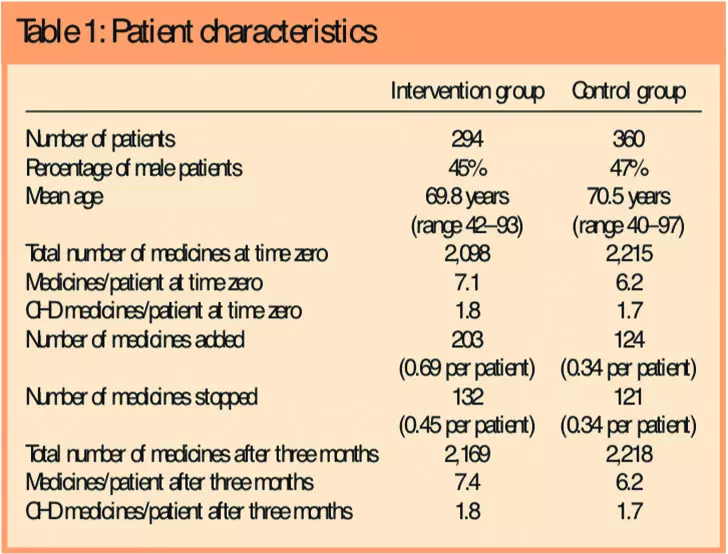

In tandem with data extraction from both the MUR and PMR for the intervention group patients, data were also extracted from the PMR system for 360 control patients — a mean of 16 control patients (range four to 20 patients) per pharmacy. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1 with intervention patients receiving more medicines than the control group both at baseline (time zero) and at follow-up.

Intervention patients were receiving 2,098 medicines at the time of the MUR and 2,169 medicines three months later. This increase in medicines use resulted from 203 medicines added and 132 medicines removed. In comparison, patients in the control group (ie, those who had not undergone an MUR) showed less activity in relation to medication additions or deletions (Table 1).

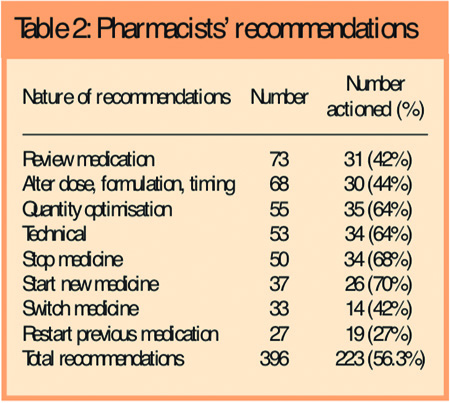

Overall, 396 recommendations (mean 1.3 per patient) on prescribed medicines were made to GPs as a result of the MUR. About three-quarters (218) of patients had one recommendation, and one-fifth (55) of patients had two recommendations. In total, 223 of 396 (56.3 per cent) MUR recommendations appear to have been acted upon by the GP.

Table 2 shows the type of recommendations made by the pharmacists.

The most common type of recommendation (accounting for 73 of the total 396) was that the patient’s medication required a review at the surgery. This category included specific suggestions such as therapy requiring review because of either a suspected adverse drug reaction or an interaction, or simply just recommending a review with no explicit reason provided by the pharmacist in the MUR documentation. Technical suggestions involved amending quantities and dosage instructions, generic to branded formulations, and deleting items no longer indicated from the repeat prescription.

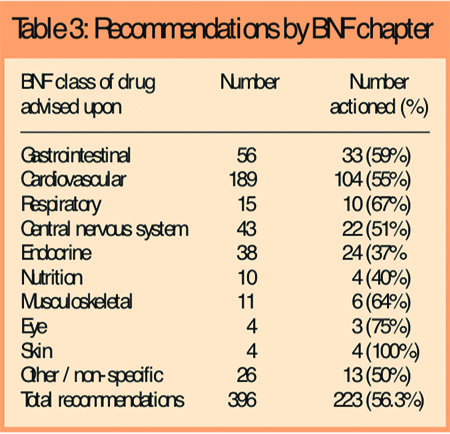

Medicines in Chapter 2 of the BNF (cardiovascular medicines) accounted for the largest proportion of recommendations (189 of the 396 recommendations). Table 3 shows the extent to which accepted recommendations were categorised by BNF chapter.

Qualitative study

Analysis of telephone interviews yielded four themes relating to perceived constraints on pharmacists, pharmacists’ confidence in undertaking MURs, educating patients’ on use of medicines, and impact of MURs on pharmacist/prescriber relations.

Theme One: Regulating MUR activity

MURs afford patients an opportunity to ensure they receive optimum use from their medication. The decision as to who would best benefit from these is one the pharmacist is best placed to make as pharmacists are most familiar with common issues related to medicines use — especially pertaining to patients on complex drug regimens. Undertaking medicines use reviews in an indiscriminate way — not on the basis of potential patient benefit — may fail to make optimum use of pharmacists’ contribution to patient care, and fails to make full use of pharmacists’ capacity to make professional judgements in the interests of patient care.

An overriding concern of employee community pharmacists, as described by others,23 is a perceived sense of having to undertake a set number of MURs to meet company set targets. This sense of having to perform MURs irrespective of patient need clearly brought into sharp relief the distinction between professional autonomy — of undertaking activities in accordance with professional judgement — and organisational edicts. In essence, pharmacists considered MURs, when undertaken to meet targets, as structured, regulated core professional practice — the antithesis of self-regulated professional practice.

Underlying this tension was a shared perception that targets were set to generate income rather than being determined by patient need (see Panel 1).

Panel 1: Pharmacists’ views on regulating MUR activity

- I sometimes do them because the company has told me to for particular people that I probably wouldn’t have done a formal MUR for . . .

- I have . . . particularly difficult (getting) to get to grips with the people who are telling you what to do, An MUR is something we normally do, it didn’t need endless bodies saying how important and how many we must do to prove we can do it.

- . . . it’s company driven and money driven a lot of it is when you look at somebody’s repeat you think they are only on three items I can do that quickly. Whereas a person on 10 items needs it but can you afford the time.

- Most of it is the company wanting the money, we can do five or six quick wins to make money but there’s no professional pride in doing it.

- . . . there is a lot of corporate pressure on it I would personally prefer to do one or two with people who really need it than churn them out at the rate of 10 per week if they’re straightforward.

- It’s part of the objective of the business of the company and there’s pressure to do it, Given the structure of them put in place, yes, I would have done them anyway but it is company policy and they’re very big on driving them

- It’s a target managed thing that area managers are trying to enforce. For me I do them out of goodwill I think it’s the type of thing a pharmacist should be doing.

- . . . it’s the time constraints that are always the issue. I would like to have 10 minutes to half an hour to go through things with patients but I’ve got people waiting for their prescriptions and the medicines have to be brought in to me to check.

This perceived impetus for MURs is important as it may compromise pharmacists’ professional judgement of who might benefit most from this service. However, MURs per se were considered a core feature of their professional activities. The issue for pharmacists was the rigidity with which they were encouraged to implement them — with an emphasis on the quantity undertaken but little perceived sense of concern regarding their quality. Notwithstanding this tension, when formalised MURs were introduced as company policy, pharmacists considered undertaking them as a gesture of largesse.

Tension between perceived corporate emphasis on throughput of MURs and pharmacists’ professional judgement on appropriateness of MUR candidates raises issues of time available for undertaking MURs. This tension between limited time available to fit MURs around their other core activities, and practitioner’s autonomy to undertake professional judgements amid company policy that might not necessarily cohere with these judgements, potentially limit the effectiveness of MURs for patient care. Others have also identified the difficulties experienced by pharmacists in providing a “normal” full dispensing service while conducting MURs.24,25

Theme Two: Confidence and experience

Although pharmacists perceived MURs as a feature of their core professional activity, when they were requested to undertake them in a formalised fashion, involving completion of report forms and so forth, some expressed a sense of trepidation and/or uncertainty prior to commencing them. Formal preparation or training to undertake MURs was largely perceived as a bureaucratic exercise in form filling rather than skills based. Effectiveness in undertaking MURs was considered by most pharmacists to be a function of experience.

Although pharmaceutical services are increasingly patient-centred rather than drug-centred, historically community pharmacists have had limited interaction with patients. Undertaking MURs, however, requires pharmacists to engage with patients to explore with them their use of medicines. This necessarily demands pharmacists to use consultations skills. Most believed that such skills were best acquired experientially.

Given that training to undertake MURs was less than extensive, and focused in part on procedures for recording the MUR, the lack of confidence expressed by many pharmacists is perhaps understandable (see Panel 2).

Panel 2: Pharmacists’ views on confidence and experience

- From my view there was an element of confidence around the paperwork, getting used to how to ask questions, confidence comes with experience.

- It’s experience . . . you can’t learn to do MURs from a book . . . everyone invents their own wheel with this one because there’s not really any consistency.

- . . . it’s a case of doing the first half a dozen and getting used to it finding your feet.

- When we first started doing them it was nervy but now we’re into it it’s something that we all do.

Direct interaction with patients is increasingly part of pharmacists’ core role but clearly this presented issues for some — though these were largely negated with experience.

Theme three: Concordance and MURs

MURs afford an opportunity for pharmacists to establish concordance with patients regarding their use of medicines. However, because of perceived pressures to meet MUR targets set by companies, this imposed time constraints resulting in pharmacists having to focus on ensuring patients appropriately adhere to their medication rather than engaging with them to establish pharmacist/patient concordance.

The perceived scope of MURs then was to inform patients about appropriate use of medicines and less about establishing a shared understanding of the risks and benefits of their medicines (see Panel 3).

Panel 3: Pharmacists’ views on concordance and MURs

- The whole idea is to help people get the best out of their medication . . . I’ve always gone along with the theory that if you tell people why they should take the medicine at a particular time or in a particular way they are much more likely to take it properly.

- For me I’d say a good MUR was one whereby the patient is understanding of all their medication and has good compliance . . . I like to feel that people know exactly what they’re doing with their medication they know exactly why they’re taking it.

- . . . if you tell people why they should take the medicine at a particular time or in a particular way they are more likely to take it properly.

- When you enlighten a patient who may have had a false perception of their medication for a long time. . . . reassure patient they are doing the right thing.

MURs were therefore perceived as instructional — informing patients of how to take their medicine — rather than facilitating them to make an informed judgement regarding their medicines use. Hence, a “good” MUR was perceived as largely an educational experience for patients.

When applied in a formulaic fashion, in which the patient is informed or educated to use their medicines effectively, MURs encourge a didactic relationship with pharmacists. The objective of MURs in such circumstances may be oriented towards ensuring that patients understand, and therefore comply with or adhere to, the pharmacist’s instructions. Although entirely appropriate, it was evident that an opportunity to explore with patients their own beliefs and expectations of medicines use — and establish concordance — was not always capitalised upon. These findings support other research suggesting that pharmacists perceive MURs as a “good idea” and that pharmacists enjoy doing them.25, 26

Theme Four: Pharmacist/prescriber relations

MURs not only give pharmacists an opportunity to develop patient-focused pharmaceutical care but also may forge closer working relationships. Pharmacists with long established prescriber relationships were unequivocal about the impact their recommendations had on prescribers. However, this level of interprofessional cohesion was exceptional. One factor militating against such cohesive relationships is logistical — the high ratio of GPs to pharmacists, with one pharmacist serving numerous prescribers. In the main, pharmacists were unsure just how influential their completed MUR forms were on prescribers.

A common concern, as described elsewhere,24 was the absence of direct feedback from the prescriber. Many pharmacists relied on the patient to inform them of changes in their prescribed medication following an MUR (see Panel 4). It has been reported that information flow is almost exclusively from pharmacist to GP, with only one in four pharmacists receiving feedback from GPs.27

Panel 4: Pharmacists’ views on pharmacist/prescriber relations

- I think they take them [MURs] seriously . . . certainly when I have felt something needs to be done then something is done.

- . . . it would be nice to know if they [MURs] are successful or not, only if a patient comes back do we see what’s been going on but that’s about it.

- You only see changes through prescriptions or the customer tells you.

- Sometimes the MURs do seem to go into the ether — I send them off and the surgery doesn’t ring up.

- I don’t get any personal feedback at all. Things may change on paper and I do see those as they go along but I never get any personal feedback from the doctors.

- The only time that we find out if something has been done is if the patient tells us or we get a prescription with the recommended change. Probably about 50:50 split between being taken up or not.

In this respect pharmacists considered undertaking MURs as analogous to working in a void — unaware of whether or not any issues raised as a consequence of MUR were responded to by the prescriber. However, this “criticism” of the GP response to MURs has to be put in the context of the fact that the medication review documentation is competing for GPs’ understanding and attention, not only with the pressures of day-to-day practice but also with a series of other government initiatives in patient care. A recent development in the MUR service is new paperwork reduced to two pages, which should only be sent to the prescriber if there is an issue to address. This should reduce the negative impact from unwanted paperwork.28

Reviewing a patient’s medicine use does not require pharmacist access to the patient’s medical records, though some pharmacists considered this desirable: “ . . . we don’t have access to the medical record — there are things I don’t know and that is why the recommendation wasn’t taken up.”

There is some uncertainty among some pharmacists as to the content of MURs in that it was felt that this may engender a form of “boundary encroachment” — with the pharmacist straying into the GP’s professional territory: “I think the GPs are very resistant to changing things if you get too clinical.”This view mirrors to some extent patients’ concerns, described elsewhere, that in conducting MURs pharmacists were straying into the doctor’s territory.27 In general the experience of delivering MURs was perceived to have enhanced pharmacists’ relationships with patients perhaps more so than with prescribers.

Our results reflect those of others. Blenkinsopp and colleagues report that over 80 per cent of pharmacists providing MUR say it has had no effect on their relationship with local GPs.27 Similarly, Elvey and colleagues report that, although MURs have the potential to increase integration with GPs, the evidence suggests that they had not yet done so and in some instances have had a negative effect on integration.23

Discussion

Delivery of MURs as part of the new pharmacy contract involves a dynamic relationship between three main players — the patient, the pharmacist and the prescriber. This relationship is governed and shaped to some extent by organisations such as the Department of Health, primary care trusts and community pharmacy (as in the strategic approach to MURs adopted by multiples and independents). So far, most of the reported research into the MUR service would suggest that it has not yet met its full expectations in terms of benefits for the main players. Monitoring of the MUR service currently focuses on process rather than content or outcomes and there has been a call for the service to be audited to provide evidence of value for money. To our knowledge this is the first study looking at the outcomes of MURs in terms of prescribed medication and the type, extent and acceptability of recommendations made by pharmacist to GPs.

Our study also adds to the widening literature on community pharmacists’ attitudes towards the service. Others have looked at the type of intervention or nature of advice given and, although the MURs in their study were aimed at a group of patients with asthma, there are some similarities and some differences with our work.29 In our study, patients undergoing an MUR had a greater medication burden (a mean of 7.1 medicines per patient) compared to a mean of 5.7 in the study reported by Kerr, while cardiovascular medicines was the category most frequently reviewed in both studies.

Although we were able to recruit 294 patients into our intervention group (those who had an MUR containing a prescribing recommendation) we had to search through 1,058 MUR forms that contained one or more of the named trigger drugs. We did not record what comments were relayed to the GP in nearly three-quarters of these 1,058 MUR forms but it is possible, for instance, that the pharmacist’s message was simply to say that no action was required or that lifestyle or medication counselling advice had been given. It may be that the GPs found such messages of little value, although in fact statements from the pharmacist that no issues were identified at the MUR could indeed be a positive outcome, and may have resulted from the pharmacist simply offering reassurance to patients that they are taking their medicines correctly.

It is clear from other reports that GPs have some disquiet over the MUR paperwork, the information it contains and what, if any, action is required of the GP.27 If GPs are unsure how to deal with their end of the MUR paperwork, or if they do not even read the reviews, then it is not surprising that our pharmacists expressed such views as questioning the influence of their MUR documentation and working in a void. Lack of engagement of GPs in valuing the pharmacists’ formalised contribution to pharmaceutical care or medicines management issues is a significant challenge.30

Although some studies describe patient satisfaction following the MUR process, the reaction of pharmacists and GPs has in the main been neutral or negative, although both these parties acknowledge the potential benefits that could arise from an effective MUR service. For instance, in a national evaluation into the new community pharmacy contract, observations related to MURs include “ . . . value and acceptability to patients and GPs yet to be established” and “MUR is an opportunity to improve patients’ knowledge and reduce wastage but effectiveness unknown.”

There are limitations to our study. Our assumption that the MUR recommendation was the sole reason for a change in prescribed medication is too simplistic because it assumes that patients receiving an MUR are not also subject to surgery-based reviews independent of the MUR.

Indeed, it could be reasoned that the more conscientiously a pharmacist selects his patients on polypharmacy for an MUR, the more likely they are to be attending clinics for diabetes, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, etc. Thus, the MUR is a complementary review, not a substitute.

Likewise, during the three-month period between data collections, the pharmacist may have made, for the intervention and/or control group, opportunistic suggestions about changes in medication made directly or indirectly (via the patient) to the GP, and this would not have been captured in our study.

Another important consideration is the assumption that patients use only the pharmacy that conducts the MUR. A GP may call a patient in to change (or start) a drug and issue a new prescription that the patient on that occasion takes to a different pharmacy. Pharmacy PMRs are unlikely to be a completely accurate record of prescribed medicines for a patient.

Any advice on changes to medication is shared with the patient and the prescriber. However, some patients’ medication may have been commenced, or recommended, by a specialist. In these circumstances, although the GP may have been sympathetic to the pharmacist’s advice, the GP may not have felt sufficiently motivated or confident to override the specialist’s initial prescribing decision or opinion.

There were also related issues around determining whether the pharmacist’s advice had been acted upon, even though using PMR data from three months after the MUR had been conducted allowed us to track any medication changes. We could be reasonable confident about changes when medicines subject to certain specific recommendations (eg, item or dose change) had subsequently altered.

However, for more vague recommendations, such as to review a medicine, that did not lead to an item change, we could not be sure whether the GP had reviewed the drug but considered its continued use appropriate or had not taken any heed of the advice to review the medicine.

In a similar vein, although the intervention group of patients showed more medication changes (203 additions and 132 deletions in the MUR group) than the control group, only a proportion of these (59 recommendations to start, restart or switch medication and 48 recommendations to stop or switch medication) can be directly associated with pharmacists’ documented advice.

The quantitative aspect of our study focused solely on prescribed medication whereas it has been argued that the main focus of the MUR is on helping patients receiving medicines to understand their therapy and how to get the best from their medication. As one of the interviewees stated: “The whole idea is to help people get the best out of their medication. . . . I’ve always gone along with the theory that if you tell people why they should take the medicine at a particular time or in a particular way they are much more likely to take it properly.” Hence outcomes from the MUR could include recommendations from the pharmacist relating to lifestyle advice or dietary advice, as well as advice on over-the-counter and prescribed medicines.

Finally, we recognise that we do not know the extent to which our results are representative of the general case because the pharmacies we visited were essentially self-selected, and the MURs we examined were those of patients taking specific CHD medication.

In summary, as well as confirming the findings of others about pharmacists’ attitudes and perceptions to MURs, we have identified and quantified some beneficial process measures around prescribed medication.At a time when the general view towards MURs seems to be one of challenges associated with improving the process and demonstration of benefit, it is rewarding to note that in our study just over half of all the pharmacists’ recommendations were apparently acted upon. Changes in medication are not necessarily typical outcomes of the MUR, since patient education and efforts to improve compliance are important aspects of the review, along with informing the GP of the full range of medication being used.

In conclusion, we strongly support the call for further development and integration of this advanced service but do endorse the comment from the Community Pharmacy Medicines Management Project that there is benefit in developing the community pharmacist’s role as a reviewer and adviser on patients’ medications.31

Acknowledgements

We thank the pharmacists who gave their time, David Jenkins for collecting data from pharmacies and Linda Matthews for transcribing the interviews. We also thank Servier for funding the project through the 2006 Servier prescribing and medicines management practice research award.

About the authors

Michael Wilcock, MRPharmS, is head of the Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Primary Care Trust prescribing support unit.

Geoffrey Harding, PhD, is a senior research fellow at Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry, Exeter.

Correspondence to: Michael Wilcock, Head of Prescribing Support Unit, Cornwall and Isles of Scilly PCT, c/o Pharmacy Department, Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust, Truro, Cornwall TR1 3L J (tel 01872 253548; e-mail mike.wilcock@ciospct.cornwall.nhs.uk).

References

- Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Advanced services. Available at:www.psnc.org.uk/pages/advanced_services.html (accessed 4 July 2008).

- Krska J, Cromarty JA, Arris F, Jamieson D, Hansford D, Duffus PRS. Pharmacist-led medicationreview in patients over 65: randomised, controlled trial in primary care. Age and Ageing2001;30:205–11.

- Zermansky AG, Petty DR, Raynor DK, Freemantle N, Vail A, Lowe C. Clinical medication review by apharmacist of elderly patients on repeat prescriptions in general practice: a randomised controlledtrial. British Medical Journal 2001;323:1340–3.

- Mackie CA, Lawson DH, Campbell A, MacLaren A, Waigh R. A randomised controlled trial ofmedication review in patients receiving polypharmacy in general practice. Pharmaceutical Journal1999;263(Suppl):R7.

- Holland R, Lenaghan E, Harvey I, Smith R, Shepstone L, Lipp A et al. Does home based medication review keep older people out of hospital? The HOMER randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal 2005;330:293–5.

- Holland R, Brooksby I, Lenaghan E, Ashton K, Hay L, Smith R et al. Effectiveness of visits from community pharmacists for patients with heart failure: HeartMed randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal 2007;334:1098

- Community Pharmacy Medicines Management Project Evaluation Team. The MEDMAN study: arandomised controlled trial of community pharmacy-led medicines management for patients withcoronary heart disease. Family Practice 2007;24:189–200.

- Anonymous. UK study fails to show benefits of medication reviews. Pharmaceutical Journal2007;279:147.

- Holland R, Smith R, Harvey I. Where now for pharmacist led medication review? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2006;60:92–3

- Ballantyne P. The role of pharmacists in primary care. British Medical Journal 2007;3341066–7.

- Pacini M, Smith RD, Wilson ECF, Holland R. Home-based medication review in older people: is it cost-effective? Pharmacoeconomics 2007;25:171–80.

- Foulsham R, Siabi N, Nijjer S, Dhillon S. Ready, steady, pause and take stock! Time to reflect on medicines use review. Pharmaceutical Journal 2006;276:414

- Wilcock M, Harding G. General practitioners’ perceptions of medicines use reviews by pharmacists.Pharmaceutical Journal 2007;279:501–3.

- Progress achieved with new pharmacy contract but room for improvement. Pharmaceutical Journal 2007;279 (Suppl):B26–7.

- James DH, John DN, Thomas R, Roberts D. General practitioners’ views about the medicines use review service. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2007;15(Suppl 2):B57–8.

- Levenson R, Celino G, Dhalla M (for Task Force on Medicines Partnership). Evaluation of Room for review: a guide to medication review. Part 2: the patient view. London: Medicines Partnership, 2005. Available at: www.npc.co.uk/med_partnership/assets/rfr_eval2.pdf (accessed 29 July 2008)

- Bissell P, Blenkinsopp A, Short D, Mason L. Patients’ experiences of a community pharmacy-led medicines management service. Health and Social Care in the Community 2008;16:363–9.

- National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease. London: Department of Health 2000.

- Blenkinsopp A, Celino G. Long term conditions: Integrating community pharmacy’s contribution. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2006.

- Carter S, Taylor D, Levenson R. A question of choice: compliance in medicine taking. London: Medicines Partnership, October 2005.

- British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. British National Formulary, no 52. London: BMJ and RPSGB, 2006.

- Harding G, Gantley M. Qualitative methods: beyond the cookbook. Family Practice 1997;15:76–9.

- Elvey R, Bradley F, Ashcroft D, Noyce P. Medicines use reviews under the new community pharmacy contract. Abstract of paper given at 13th Health Services Research and Pharmacy Practice Conference April, 2007. Available at: www.hsrpp.org.uk/VolAbstracts.pdf (accessed 29 July 2008)

- Hilton A, Edmondson H, Featherstone V. A report on a focus group discussion on the localimplementation on medicines use reviews (MURs). Abstract of paper given at 13th Health Services Research and Pharmacy Practice Conference, April 2007. Available at: www.hsrpp.org.uk/VolAbstracts.pdf (accessed 29 July 2008)

- Latif A, Boardman H. Community pharmacists’ attitudes towards medicines use reviews and factors affecting the numbers performed. Pharmacy World and Science 2008. Online First DOI 10.1007/s11096-008-9203-x.

- Ewen D, Ingram MJ, MacAdam A. The uptake and perceptions of the medicines use review service by community pharmacists in England and Wales. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2006;14(Suppl 2):B61–2.

- Blenkinsopp A, Bond C, Celino G, Inch J, Grey N. National evaluation of the new community pharmacy contract. London: Pharmacy Practice Research Trust, 2007.

- Shorter MUR form will aid communication with GPs. Pharmaceutical Journal 2007;279:701.

- Kerr C. Medicines use reviews experience in the field: Lloydspharmacy. Abstract of paper given at the British Pharmaceutical Conference, Manchester, 6 September 2006.

- Campion P, Hilton A, Irving G. Shared prescribing? A focus group study with community pharmacists.Primary Health Care Research and Development 2007;8:308–14.

- Tinelli M, Bond C, Blenkinsopp A, Jaffray M, Watson M, Hannaford P. Patient evaluation of a community pharmacy medication management service. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2007;41:1962–70.