Abstract

Aim

To explore the images and perceptions of pharmacy with potential applicants to undergraduate pharmacy education.

Design

Four interactive focus groups involving 40 volunteer year 12 students (age 17). The focus group theme plan was designed after a review of relevant literature. A novel approach was employed using photographic images of pharmacists and doctors in varied settings.

Subjects and setting

The research was carried out in six schools in the West Midlands, UK.

Results

The students presented a rather negative image of pharmacy as a boring occupation in a laboratory or the back of a shop. Most had little idea of what pharmacists actually do. Unlike nursing, they were unaware of positive role models in the media. The small number who did have a realistic idea of pharmacy based it on their previous work experience in pharmacy.

Conclusions

The focus group technique is useful for exploring hitherto untapped perceptions of the profession. Undertaking research with year 12 students provided some useful insights into the ways in which pharmacy as a profession is perceived. Although no claims to generalisability are made here, the results were fed into the design of quantitative surveys. The somewhat negative image presented suggests that the profession has more work to do in marketing itself to young people as a potential career choice.

There is currently considerable interest in the UK in studying aspects of the pharmacy profession because of the changing pharmacy agenda and the need to understand the workforce and its motivations. This qualitative study set out to identify perceptions of pharmacy held by potential applicants to training for the profession.

Pharmaceutical services studies

Over the past 20 years a considerable body of research has been undertaken into public perceptions of pharmacy, exploring public use of, and satisfaction with, existing and new pharmaceutical services.1–3 It was through this research that we were reminded that the first person a customer meets in a community pharmacy is a member of the sales or counter staff. One project which explored perceptions of the general public considered the contradictions: do consumers recognise the pharmacist as a highly trained and knowledgeable health care professional who plays a vital role in the provision of primary health care services, or simply as a shopkeeper selling drugs instead of newspapers?4 The author concluded that pharmacy is held in high esteem by its users and that pharmacy itself has a highly scientific basis which allows the “expert” to “shroud their work in mystery”.

Undergraduate studies

Although several studies have explored various dimensions of pharmacy undergraduate education,5–10 an overview of pharmacy practice literature suggested that by comparison with the focus on service provision, little has been written about the image of pharmacy as a profession among young people who have not already enrolled to study pharmacy.

The potential undergraduate

Since the early 1980s, the schools of pharmacy in the UK have not had to concern themselves with marketing their courses. There was always sufficient demand from students for the limited number of training places and consequently little attention was paid to the image of pharmacy. The image potential students might hold of pharmacy was never considered. The advent of new schools of pharmacy without a commensurate increase in total application numbers means that schools now have to market themselves to attract good quality applicants. At the same time the changing nature of health professional regulation in the UK places greater demands upon students, so they should be aware of the challenges before they begin their studies. In these circumstances, understanding the match of the students’ expectations and professional reality becomes critical.

The purpose of this study was to explore the perceptions of year 12 students, aged 17, who were studying AS levels (ie, they were in the first year of their A level studies) and who might consider applying to study pharmacy. The study reported here served two objectives: first to explore students’ knowledge of pharmacy as a profession and secondly to produce insights or key concepts that could be used in subsequent quantitative studies. The findings informed the design of research into career aspirations, motivations and expectations.11

Method

The image of pharmacy was explored in four focus groups, involving 40 students. As Bryman and Bell12 note “the focus group offers the researcher the opportunity to study the ways in which individuals collectively make sense of a phenomena and construct meanings around it”. One member of the research team (KH) took responsibility for this phase by designing the research instrument and organising and facilitating the focus group fieldwork. Ethical approval was given by the Aston University Research Ethics Committee.

Sampling frame

The number of focus groups that should be undertaken depends on the time and resources available. The focus group facilitator consulted the university’s schools liaison office for advice on which education institutions to approach. There were three types of education establishments: private direct grant, community comprehensives, and traditional sixth form colleges. In 2004, 16 schools and sixth form centres in the West Midlands were approached and six expressed interest in participating. Unfortunately two schools withdrew due to the tight timetables around examinations. No further schools were approached and although it might have been possible to approach two replacement schools, the tight timetable around examinations and internal school priorities precluded that possibility.

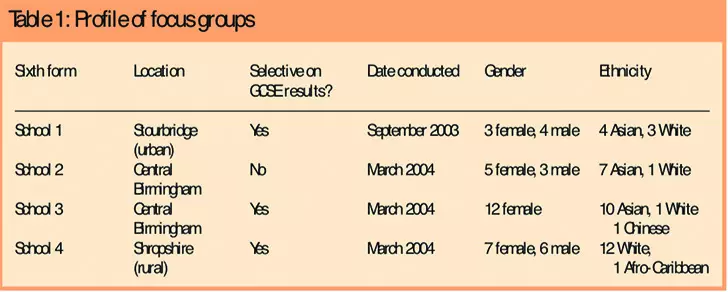

Consent was obtained from each school to conduct a focus group with year 12 students. At this point in their studies, the students were studying four or possibly five AS level subjects. Students for the focus groups were chosen on the basis that they were studying appropriate AS level subjects for eventual entry into pharmacy, ie, the sciences, including chemistry. It was not assumed that they were representative of all students in that age group or nationally, but that they might be expected to have something to say about pharmacy as a career. Contact was made through the heads of science at each school who publicised the focus groups to appropriate student groups and asked for volunteers. The sample was from a mixture of educational establishments (used as a proxy for social class) which ensured a cross section of cultural and socio-economic backgrounds. Three of the groups were mixed gender and one was from an all-girls school. The profile of each the focus groups is summarised in Table 1. Of the 40 participants, 11 were actively considering pharmacy as a possible subject for study at university, three of whom definitely wanted to study pharmacy.

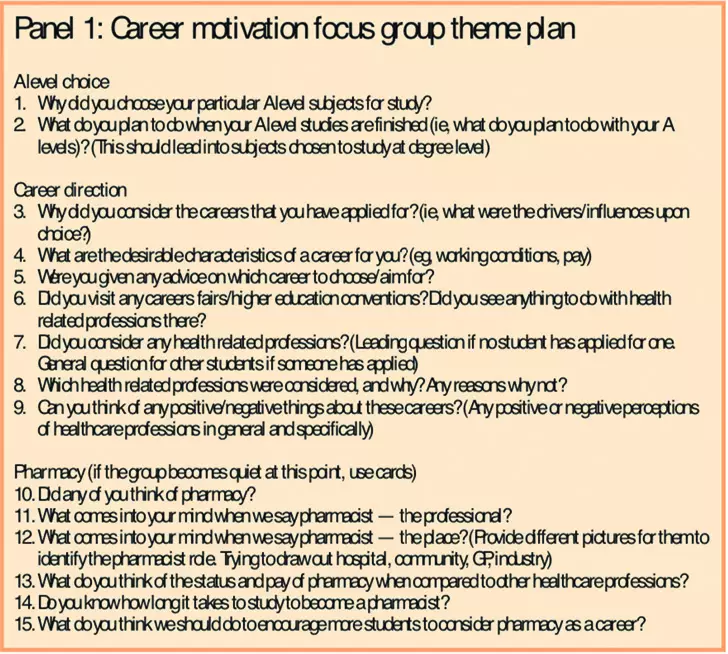

Research instrument

A theme plan was designed by the facilitator based on the core conceptual issues that we wanted to explore (Panel 1). The core themes included: choice of A level study and future plans, career motivation and perceptions of the status of healthcare professions and of pharmacy within that framework.

The plan was peer reviewed by the research team and revised.

The facilitator used a novel technique to query the nature and image of pharmacy as a career with the groups by presenting a series of photographs, taken from The Pharmaceutical Journal, Hospital Pharmacist and other pharmacy publications, and cards with work/profession related concepts. At this point students were faced with images of behaviour or activity that they might never have seen before. The changing nature of pharmacy in the past 20 years has provided much more “behind the scenes” clinical work for pharmacists, which it would be unreasonable to expect the lay public to identify.

The facilitator used this phase of the discussion to share information with participants who might not be expected to understand what they were looking at in the images and then to examine the impact the new information had on their attitudes. An added benefit of focus group methodology is that one is not rigidly fixed into a structured one-way interaction, as in survey methodology, but it can be used in an interactive way to challenge ideas. A good facilitator has to know his or her topic well enough to explain ambiguities to participants if need be.

Six photographs were used to explore the participants’ depth of knowledge of the work of a pharmacist:

- A pharmacist in a white coat in a community pharmacy

- A pharmacist in a white coat with a doctor and a patient in a hospital ward

- A pharmacist in a white coat in a hospital pharmacy dispensary

- A pharmacist working in an aseptic suite, in appropriate clothing

- A pharmacist in less formal wear working with a group of children

- A pharmacist and a GP in a general practice surgery

The phrases on show cards to test perceptions were a mixture of positive and negative concepts:

- Well paid, interesting, flexible, respected, exciting, variety, career progression

- Boring, hard work, repetitive, not challenging

The focus group discussions lasted between 40 minutes and one hour and were conducted during the lunch break at each school. The facilitator offered to answer any questions about pharmacy once the discussions were completed and the tape machine turned off. The focus groups were recorded and the tapes transcribed. Paper copies were analysed according to core themes by two of the team, notes compared and checked. An additional reason for caution over the number of focus groups undertaken purely for scoping and developmental work is the sheer volume of paperwork produced from tape transcript, which then has to be analysed. By the final focus group the facilitator was confident that the discussion had reached saturation and no new material was forthcoming.

Results

Image of pharmacy

What image did students have of pharmacy? Without exception, students said that their first impressions of pharmacy were that it was a boring occupation and they thought that pharmacists were either stuck in a laboratory or in the back of a shop. The concept of “white coat” was commonly used, and this was before exposure to the pictorial images. Words used by various participants to describe pharmacists were “unsociable”, “reclusive”, “hermits”. There was a general impression that pharmacists just sat in the back of a shop and “made up drugs” or “mixed up penicillin”, as the following transcript suggests:

Moderator: What image do you get of the pharmacist?

Participant 1: Boring.

Participant 2: White coat.

Participant 3: Being stuck in a lab.

Participant 4: Not in a lab, in the back of a shop. Participant 1: All enclosed, and . . .

Participant 4: Yeah, enclosed. That’s a good word. (School 3)

Generally, there was agreement that pharmacy was an enclosed profession with a constrained working environment and little contact with other people. In addition, students thought that there was not a great deal involved in being a pharmacist. Upon further discussion, students began to mediate this opinion into something more encompassing. The predominant identification was pharmacy as shop work and, as such, participants thought that working in a shop was boring, repetitive, not exciting, not challenging. One young woman said:

It’s not going to be challenging in a chemists I don’t think because you’re just giving out drugs all the time. Not like in industry. (School 2, Asian female 1).

The focus group participants appeared to know little about new clinical opportunities for pharmacists or about work in settings other than the community.

Their contrasting image of the profession was that it was generally well respected and that career progression was possible. When the show card “flexible” was used, participants in one of the groups agreed that it was a flexible career — in the sense that a professional with the same skills and knowledge can do the work just as easily. One participant who stated that pharmacy offered opportunity for flexible employment, allowing time off to have a family or pursue other activities, was reinforcing the notion of easily substituted staff because:

It’s competitive like — you can always get someone else to do it. (School 2, Asian male)

It was generally agreed that pharmacy was likely to be much more interesting out of the shop, particularly in a laboratory.

What do pharmacists do?

Images were explored further with the use of photographs taken from various pharmaceutical publications, as described earlier. When shown the pictures of pharmacists at work, those where the pharmacist was dressed in a white coat were easier for the participants to describe the contribution the pharmacist might be making in the scene. Two photographs showed pharmacists working closely with doctors in a GP surgery and in a hospital. In both cases, the groups were not able to describe the contribution of the pharmacist. It was at this point that the facilitator shared new information with them.

Some participants were dubious as to whether there was variety in pharmacy work because they were unsure exactly what the job of a pharmacist entails. When pharmacist prescribing was mentioned by the facilitator, some participants saw this to be an exciting development and that it could change their opinion of the profession. However, others were cautious and concerned that the public would not welcome pharmacist prescribing, saying:

The public won’t trust pharmacists to prescribe as they don’t have a medical degree. (School 1, Asian male)

Generally, the participants reiterated that they did not really know what pharmacists do and would like more information. Few of the students, including some of those who had work experience in a pharmacy, could state confidently the length of study to become a registered pharmacist, although most were confident of the length of study for medicine.

A potential career?

The final point for discussion explored what mechanisms are needed to encourage more people to consider pharmacy as a career. How can we change the uninformed perception portrayed here? The overwhelming answer was to change the image of the profession. Participants thought that the general public just saw pharmacists as being in a shop and did not perceive it as a skilled profession. Participants at two of the focus groups (Schools 3 and 4) suggested that the profession should publicise itself through television:

Someone ought to do a programme about pharmacists. (School 3, white female)

The participants had little to suggest for changing the image of pharmacy, but there was a positive request for more information to be made available on pharmacy as a career.

Career direction: influencing factors

A few of the participants were considering applying to study pharmacy. What had influenced and motivated them? The interesting finding was the importance of work experience. This had a high impact on many students.

“…my future was a total blank… it all came into perspective when I did work experience.” (School 3, Asian female 2)

Careers advice, from a variety of sources, was cited by some as a reason for choosing a particular career path, although responses in this area were varied. Some students had found careers advice useful, but most students had not had any great careers advice before the start of their year 12 studies. All students said that careers advice was aimed at those in year 13, which may be too late. The majority considered that the advice provided was not always useful to them.

Family members were also an influencing factor on the choice of career for some.

My grandad . . . and my uncles are all doctors and my parents want to carry on the doctor thing in my family. (School 3, Asian female 5)

This is an interesting comment since it suggests that medicine is a first choice and maybe pharmacy is the default option.

One participant mentioned that “Asian culture” was an influencing factor; in her particular focus group this provoked a large amount of agreement (most of the group were of Asian descent). Research on the UK pharmacy profession by Hassell et al13 has shown the importance of pharmacy as both a scientific career and giving many opportunities for pharmacy ownership. Study participants confirmed that a career in pharmacy might be of interest to this ethnic group in particular because of its opportunities for social mobility, for self-employment as a pharmacy locum (a status chosen by more than a quarter of the active pharmacist population and more than a third of all community pharmacists)14 as well as for entrepreneurial reasons.

Career direction: motivating factors

Groups explored their own motivations behind choosing a career. The most frequently mentioned reason, from all groups, was that the career had to be enjoyable and interesting and something that could be done for a long time:

Something you can carry on until you’re old. (School 2, Asian female 2)

Participants did not want to be in a job that they did not like. Job security was also often cited as a reason. They wanted a career that was challenging. The status and reputation of a career was a factor, with medicine mentioned specifically as a career with a good reputation.

The all-female focus group rated the ability to work part time as important, along with the desire to help people and make a difference in people’s lives. A definite career path, with good prospects, was a factor brought up by all focus groups. Money was not mentioned as a high priority and most students recognised that in the careers they were aiming for, money only came after a lot of hard work.

Status of healthcare professions

The students had clearly formed their own hierarchy of professional status. They were asked to rank a list of health professions (medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, nursing, optometry, physiotherapy, occupational therapy) according to their perceived status in the eyes of the general public. Every group placed medicine as first in this ranking, with nursing second. Participants found this task difficult due to a lack of knowledge of what each of the remaining professions actually entailed, again emphasising their general lack of basic knowledge from which to form a career decision.

Discussion

This study adds to the picture we are building of the profession by exploring perceptions with young people who have not yet committed to a career in pharmacy.

Limitations

The focus group methodology is ideal for exploring hitherto untapped topics, to develop core concepts and ideas for future research. The limitations of the study derive principally from the methodology itself. Focus group results tell you what, how or why, but are not about cause and effect. Neither are they generalisable. It may be the case that the interactive nature of the focus groups, whereby the facilitator discussed the wider range of activities undertaken by pharmacists, may have introduced some bias into the discussion. However, we consider that without this added interaction when working with respondents from the public who have little in-depth knowledge about pharmacy, the discussion would not have produced the interesting insights reported here.

The facilitator observed that nothing new was obtained from participant responses by the fourth group, which suggests that the material was suitably covered and we might therefore claim that the opinions are typical of young people in that age group, studying science subjects.

There were some differences between groups in terms of knowledge, experience and willingness to explore the ideas in a focus group format. There were differences based on the type of institution and the socioeconomic group that each represented. In the selective sixth form environments, the majority of participants had definite ideas about their future careers, while the non-selective sixth form participants had less definite ideas. This is despite the fact that all of the participants had similar access to careers guidance and information.

Value of work experience

One of the interesting findings from the focus group work was that four students had practical work experience in a pharmacy, which had inspired them and confirmed their ambition to be a pharmacist. In a follow-up survey, 44 per cent of pharmacy undergraduate respondents11 (n=1,428) listed work experience as one of the important influencing factors, thus reinforcing the notion that work experience in a pharmacy can be an extremely valuable way of promoting the profession. This requires action at the local level and is perhaps a task that could be taken up by local pharmaceutical committees.

Studying science

It is interesting to note that a large majority of participants were studying chemistry with biology and that this was seen as a useful combination of subjects for admission to a number of university courses (ie, the students were hedging their bets). All of the participants were studying AS level subjects which, if continued to A level, would lead to them being suitably qualified to read pharmacy at university, with a large proportion also being interested in medicine. These students seemed to be much more knowledgeable as to what was involved in studying medicine, particularly the women; it would seem that information on medicine as a career is much more accessible. We have subsequently confirmed that pharmacy can be the default option to medicine. There was interest in industry and laboratory employment, which actually has few openings.

Careers and professional information

The findings suggest that there is scope for better marketing of pharmacy as a career option, maybe at the local level as well as expecting the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain to take a lead. There was general consensus that there was a lack of information about being a pharmacist. Once the photographs of pharmacists in the workplace were shown and their roles explained, many of the students showed more interest in pharmacy. We checked what was available and found that at the time of the study there was no coherent information package for pharmacy readily available to either secondary school students or their careers advisors. In addition, there seemed to be a communication and publicity gap about the profession. This is an issue that could be explored when careers are promoted by the schools and the Society. Since the study, the Society has made some advances in marketing the career through its website, national press supplements and career materials.

Beyond the white coat

The image of pharmacy portrayed by this group of students was not a positive one. Pharmacy was ranked lower in status than other healthcare professions and the students held what we hope is a somewhat out of date vision of the pharmacist as the person in a white coat in a shop.

This person was also seen as possessing skills that were easily substituted. It would seem that the “white coat” is a barrier and is still the pervasive public image of a pharmacist, although we may have contributed to the stereotype by the images used.

A recent observation about UK pharmacy and its public image tends to confirm the focus group participants’ opinions. This voiced what many people may have thought, but been unwilling to commit themselves to in public — that many community pharmacies “are devoid of style, aesthetics, order, identity even”.15 That description of community pharmacy, imprinted on the subconscious of the public, derives from their own knowledge and experience of community pharmacy. This in turn moulds the public opinion of what the profession is.

Conclusion

Despite their stereotyped and somewhat limited perceptions of pharmacy as a career, many of the students who took part in the focus groups were interested in what pharmacy had to offer. Discussions once the tape was stopped at the end of the session were lively, particularly once the “white coat” image was dispelled. This small-scale qualitative study gave us some useful information to test in subsequent quantitative surveys. More usefully, it has shed some light on the practical ways in which the marketing of pharmacy as a professional healthcare career needs to move.

Acknowledgements

The research was commissioned by the Pharmacy Practice Research Trust funded with a grant from the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain.

This paper was accepted for publication on 11 November 2007.

About the authors

Jill Jesson, PhD, is lecturer in the marketing group, Aston Business School, Aston University, Birmingham.

Keith A. Wilson, PhD, FRPharmS, is professor of pharmacy, Chris A. Langley PhD, MRPharmS, is lecturer in pharmacy practice, and Katie Hatfield, BSc, MRPharmS, is teaching fellow in pharmacy practice, at the School of Life and Health Sciences, Aston University.

Correspondence to: Jill Jesson, Aston Business School, Aston University, Birmingham B4 7ET

(e-mail j.k.jesson@aston.ac.uk)

References

- Jepson M, Jesson J, Kendall H, Pocock R. Consumer expectations of community pharmacy services. A report for the Department of Health: Aston University and Midland Environment Ltd; 1991.

- Hassell K, Rogers A, Noyce P. Community pharmacy as a primary health and self care resource: a framework for understanding pharmacy utilisation. Health and Social Care in the Community 2000;8:40–9.

- Bissell P, Ward P, Noyce PR. Variation within community pharmacy. 1. Responding to requests for over-the-counter medicines. Journal of Social and Administrative Pharmacy 1997;14:1–15.

- Varnish J. Drug pushers or health professionals: the public’s perceptions of pharmacy as a profession. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 1998;6:13–21.

- Booth TG, Harkiss KJ, Linley PA. Factors in the choice of pharmacy as a career. Pharmaceutical Journal 1984;233:420.

- Rees JA. Why male and female students choose to study pharmacy. British Journal of Pharmaceutical Practice 1984;7:90–6.

- Roller L. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors in choosing pharmacy as a course of study at Monash University 1999–2004. Pharmacy Education 2004;4:191–264.

- Silverthorne J, Price G, Hanning L, Cantrill J. Factors that influence the career choices of pharmacy undergraduates. Pharmacy Education 2003;3:161–7.

- Kritikos V, Watt HMG, Krass I, Sainsbury EJ, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ. Pharmacy students’ perceptions of their profession relative to other health care professions. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2003;11:121–9.

- Taylor KMG, Harding G. The Pharmacy degree: The student experience of professional training. Pharmacy Education 2007;7:83–8.

- Wilson K, Jesson J, Langley C, Clarke L, Hatfield K. Pharmacy undergraduate students: career choices and expectations across a four-year degree programme. Report commissioned by the Pharmacy Practice Research Trust; 2006.

- Bryman B, Bell E. Business Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003.

- Hassell K, Noyce P, Jesson J. White and ethnic minority self employment in retail pharmacy in Britain: an historical and comparative analysis. Work, Employment and Society 1998;12:245–71.

- Hassell K, Seston L, Eden M. Pharmacy Workforce Census 2005: Main Findings. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2005.

- Florence A. Baby clothes, sandwiches and T-shirts spoil pharmacy’s professional image. Pharmaceutical Journal 2006;277:516–7.