Abstract

Aim

To measure provision of medicines use reviews (MURs) in the first year of implementation and to investigate barriers and facilitators to uptake of the service.

Design

Postal questionnaire survey of pharmacy leads in primary care organisations and structured telephone interview of strategic health authority (SHA) pharmacy leads. Analysis of routinely collected data on MUR.

Subjects and setting

Pharmacy leads in 28 primary care trusts in England and three local health boards in Wales, representing a 10% stratified random sample of primary care organisations (PCOs), pharmacy leads in SHAs and the Welsh Assembly Government.

Results

Overall, 38% (range 13–60%) of community pharmacies had claimed payment for providing MURs in the first year of the service. There was a seven-fold difference in the mean number of MURs per providing pharmacy, with a mean of 35.7 (8.3–61.2). Pharmacies from multiples were over-represented in the contractors claiming payment for MURs (71% versus the national percentage of community pharmacies that are multiples, 57%). Multiples undertook 83.6% of all the MURs conducted in our sample PCOs. The number of MURs provided represented 6.8% of the theoretical financially capped maximum. Most SHA and PCO respondents viewed MURs as a part of the new contract with considerable potential but where progress was often slow. PCOs had used a range of methods to support the roll out of MUR implementation locally.

Conclusion

The uptake and spread of the MUR service in its first year accounted for only a small proportion of allocated funding. There were wide inter-PCO variations in the level of MUR provision. Most of this variation was accounted for by the percentage of providing pharmacies that were from multiple groups. Stakeholders identified a number of barriers to provision. These findings suggest that further action is needed to support and embed the MUR service.

For many years commentators have argued that the knowledge and skills of community pharmacists are under-used in their daily practice. Community pharmacists themselves believe they have more to contribute to patient care.1 A new service, “Medicines use review and prescription interventions”, was introduced into the NHS in England and Wales in 2005 as part of a new community pharmacy contractual framework. The service is both novel and significant for a number of reasons. It is the first national service in which community pharmacists are remunerated by the NHS to provide a consultation to a patient specifically to discuss his or her medicines. (According to the Department of Health, a medicines use review aims “with the patient’s agreement, to improve his knowledge and use of drugs by in particular (a) establishing the patient’s actual use, understanding and experience of taking drugs; (b) identifying, discussing and resolving poor or ineffective use of drugs by the patient; (c) identifying side effects and drug interactions that may affect the patient’s compliance with instructions given to him by a health care professional for the taking of drugs; and (d) improving the clinical and cost effectiveness of drugs prescribed to patients thereby reducing the wastage of such drugs.)

Lack of remuneration has been cited in the past as a key barrier to the implementation of new community pharmacy services2 so the funding allocated for MUR addressed this. Furthermore the service specification requires pharmacists to send a copy of their reports to the patients’ GPs, including any recommendations about potential changes needed to the patients’ prescribed medicines. This is the first time such formal communication has been a requirement within a national community pharmacy service specification. MUR thus provides an opportunity for community pharmacy to develop a service providing direct care to patients that makes better use of skills and knowledge, and to develop relationships with GPs.

There are specified mandatory entry requirements for provision of MURs, including accreditation of the pharmacist through higher education institutions, and of the pharmacy premises by primary care organisations (PCOs). More specifically, the pharmacy has to have a consultation area which is “a clearly designated area for confidential consultations which is distinct from the general public areas of the pharmacy; and must be an area where both the person receiving MUR services and the registered pharmacist providing MUR services can sit down together and talk at normal speaking volumes without being overheard by other visitors to the pharmacy or by any other person, including pharmacy staff ”.3 In the first year of the service an accredited pharmacy could claim remuneration for providing up to 200 MURs (this was increased to 250 late in 2005).

PCOs (primary care trusts in England and local health boards in Wales) are responsible for the implementation and monitoring of the new contract. Guidance to PCOs included a toolkit to support the development of a local pharmaceutical needs assessment to inform contract development and service commissioning. The service specification for advanced services permits PCOs to agree locally with contractors which priority groups should be targeted for MURs by local community pharmacists. Strategic health authories (SHAs) have responsibility for performance management of PCT functions.

The research reported here was part of a wider evaluation of the implementation of the new pharmacy contract. The aims relating to MUR were to:

- Determine the numbers of MURs provided by individual pharmacies in a sample of PCOs in England and Wales

- Explore the association between pharmacy ownership and levels of provision

- Identify the actions taken by PCTs to support local implementation

- Explore the perspectives of NHS stakeholders at PCT and SHA level on progress in implementation of the MUR service

Methods

The study was designed to enable correlation of data on MUR volumes in a sample of PCOs in England and Wales with information on the local PCO perspective and on the national picture.

It included a postal survey of PCOs, a telephone survey of SHAs and review of data on payments claimed for MUR. A stratified random 10 per cent sample of PCOs in England and Wales was drawn. Stratification was at SHA level for England (n=28) and regional level for Wales (n=3).

A postal questionnaire was sent to the pharmacy lead in each of the 31 PCOs during May 2006, with up to three reminders during May and June. Before distribution of the survey each PCO was telephoned to ascertain the name and contact details of the pharmacy lead. The questionnaire used for the survey was developed from that used in previous national surveys of PCTs in England conducted by Keele with Webstar Health in 2003 and 2004 and following additional pilot work.4 The questionnaire comprised a mixture of closed and open questions and covered a range of topics with respect to the new contract. In relation to the MUR service respondents were asked whether their PCO had a strategy for medicines review (by which we mean all types of review, including MURs and clinical medication review, and, if so, if it included community pharmacists). They were asked whether their PCO had agreed with contractors priority patient groups to receive MUR and, if so, which were the patient groups. They were also asked what actions their PCO had taken to support local implementation of MUR, and about the nature and frequency of contact between their local pharmaceutical and medical committees.

A structured telephone interview was carried out with the person within each SHA identified as having lead responsibility for monitoring the implementation of the community pharmacy contractual framework (the contract). The relevant individual at the SHA was identified using documentary sources and direct contact. A potential respondent was identified for 26 of the 28 SHAs; in two cases there was no member of staff with the relevant information because of staffing changes in the organisations. In the case of implementation of the contract in Wales we approached the pharmacy lead in the Welsh Assembly Government for a strategic overview.

The interview schedule was piloted with one SHA pharmacy lead. Respondents were sent the list of questions in advance. Respondents were asked which aspects of the contract had, in their view, gone relatively well and for suggestions about ways in which they thought it could be improved. Interviews were conducted by telephone and detailed notes were taken, including verbatim comments. Up to four appointments were made if respondents were unable to complete the interview at the time arranged. Interviews lasted between 15 and 40 minutes and were conducted in April and May 2006.

A request was made to the Prescription Pricing Division of the NHS Business Services Authority for volume data for MURs in the 28 sample PCTs in England during the first year of the service (1 April 2005–31 March 2006). Data were requested at individual pharmacy level using the Prescription Pricing Division categories of “independent” and “multiple” (more than five pharmacies) to enable any differences by pharmacy ownership type to be explored. The same data request was made to the three sample LHBs in Wales.

An application was made to the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee and then to local NHS research and development organisations in the 31 PCOs. All gave authorisation for the research to proceed.

Data management and analysis

Questionnaire and interview data were subjected to both quantitative and qualitative analysis. Data from the PCO survey were entered into SPSS 14.0 for Windows and then subjected to analysis, which included simple frequencies, cross tabulation and tests for association (chi-squared). Data from the SHA telephone interviews were analysed manually.

Qualitative data from SHA and PCO respondents were analysed thematically using the framework method.5 Illustrative quotations are presented in the results section, anonymised for each SHA (including the Welsh Assembly Government) and PCO and using a numerical code.

The percentage of pharmacies that had claimed for providing MURs in 2005–06 was calculated for each PCO. To enable benchmarking across PCOs rates of provision of MUR per 1,000 population and 1,000,000 prescriptions were calculated for each PCO. There are some limitations to these rates because the population and prescription data are not available with adjustment for dispensing doctors. Despite these limitations the indicators provide a basis for comparison between PCOs. The relative volume of MURs by multiple and independent pharmacy providers were calculated because anecdotal reports suggested that provision was substantially higher in the former.

Results

Response rates

The overall response rate for the SHA survey was 86 per cent, with data collected from 24 of the 28 SHAs in England plus the Welsh Assembly Government (25/29). In England 22 people were interviewed representing 24 SHAs. Two SHAs were unable to identify a member of staff with sufficient knowledge of implementation of the contract to answer our questions and two declined to take part. In Wales one person representing the Community, Primary Care and Health Services Policy Directorate of the Welsh Assembly was interviewed.

Twenty-nine PCOs (94 per cent) responded to the questionnaire, 28 of which answered the series of questions on the implementation of advanced services.

Respondents provided extensive written comments in answer to the open questions on positive and negative aspects of the contract, barriers and suggestions for the future. Those which related to MUR were extracted and analysed.

The PCOs exhibited wide sociodemographic variation. The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) in the sample ranged from 1 to 251 and the estimated unemployment rate from 2.62 to 10.32 per cent. The percentage of the population from black and ethnic minorities ranged from 1.86 to 55.10 per cent. Eight of our PCTs had “spearhead” status (of the national figure of 88 for England) and seven were recipients of the Neighbourhood Renewal Fund. (Spearhead PCTs were announced in 2004. They were described by the Department of Health as the most deprived areas in England and were the first to receive funding for health trainers, stop smoking services and school nurses.) Finance deficits at the end of 2005–06 ranged from a surplus of +1.9 per cent to a deficit of –4.1 per cent.

Participation of PCOs in national NHS initiatives was used as a further method to assess the representativeness of our sample. Sixteeen of the English PCTs had been sites of the Medicines Management Services Collaborative and seven were pathfinder sites for repeat dispensing (two in wave 1, five in wave 2). Three (of 28 nationally) were currently sites for the National Prescribing Centre Community Pharmacy Framework Collaborative that was established to support implementation of essential services within the new contract. With respect to participation in NHS initiatives the sample was representative of the total population of PCOs.

MUR data were supplied by the Prescription Pricing Division for the 28 English PCTs in our sample. The three Welsh LHBs supplied their MUR data, giving a 100 per cent response.

MUR provision

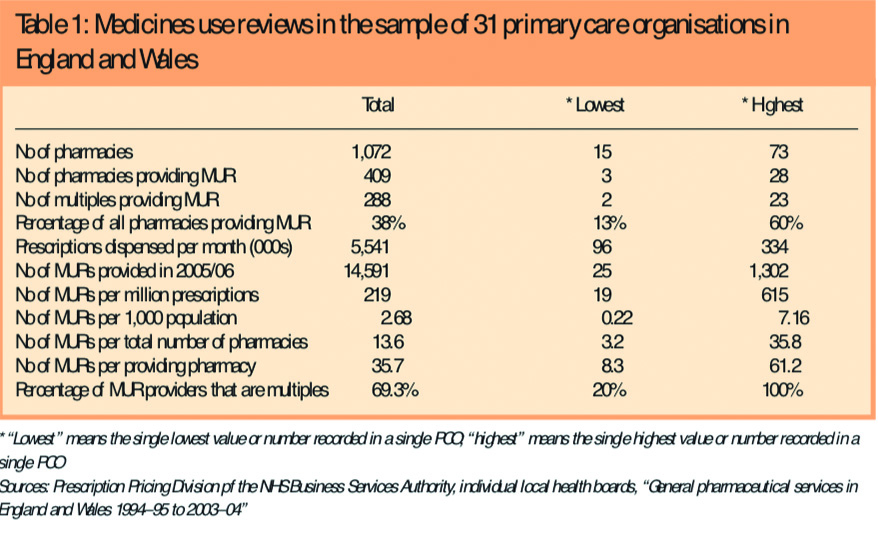

MUR provision in the 31 PCOs is summarised in Table 1.

Pharmacies in our sample claimed payment from the Prescription Pricing Division and Health Solutions Wales for a total of 14,591 MURs between 1 April 2005 and 31 March 2006, a mean of 471 per PCT. Analysis of the provision of MURs using PCO level prescription and population statistics showed a 32-fold difference in MURs per million prescriptions dispensed across our PCOs (19 to 615). The number of MURs per 1,000 population ranged from 0.22 to 7.16, representing a 33-fold difference.

Overall 38 per cent of the community pharmacies in our sample of PCOs had claimed payment for providing MURs in the first year of the service. The percentage of pharmacies claiming payment in the sample PCOs ranged from 13 to 60 per cent. Multiples were over-represented among the contractors claiming payment for MURs (70 per cent versus the national percentage of community pharmacies that are multiples, 57 per cent) and pharmacies from multiples undertook 83.8 per cent of all the MURs conducted in our sample PCOs. There was a seven-fold difference in the mean number of MURs per providing pharmacy, with a mean of 35.7 (range 8.3–61.2).

Based on the original cap of 200 MURs per pharmacy, the volume of MURs conducted in the PCOs in our sample represents 6.81 per cent of the maximum of 214,400 for which funding was allocated in the contract.

Targeting of MURs

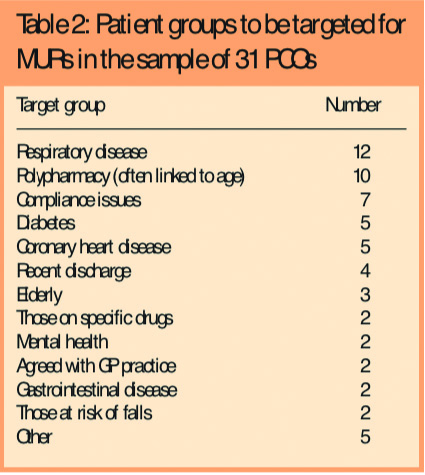

All except two of the PCOs reported having agreed with contractors the patient groups that should be targeted for medicines use review (see Table 2).

Respiratory conditions and polypharmacy were the most frequently cited. Other patient groups included those with Parkinson’s disease, housebound patients, those with stroke, children on three or more medicines, and care home residents (one PCO each).

Nineteen of the 26 PCOs that had identified target groups (73 per cent) reported that their PCO had used existing PCO priorities to identify these target groups. Five had used their pharmaceutical needs assessment to do so, eight had identified the target groups in “other” ways. These included the prescribing committee (two PCOs), the implementation group (two PCOs) and through local discussion (two PCOs).

Strategic approach to review of medicines

In order to ascertain whether and how community pharmacists and MURs featured in PCOs’ strategic approaches to medicines review, we asked respondents, first, whether they had a strategy for medication review, second, if it included community pharmacists and, finally, if it included MURs.

Sixteen of PCOs (55 per cent) reported that they had a strategy for medication review. The professional groups mentioned in the strategies included GPs (all 16 PCOs) and, with decreasing frequency, practice pharmacists (13 PCOs), nurses (11 PCOs) and community pharmacists (nine PCOs). Of the nine PCOs that included community pharmacists in their strategies, two said that their strategy did not include MUR.

PCOs that reported including community pharmacy and MUR in their medication review strategy were more active in providing support to roll out MUR. Such support included identifying priority groups, undertaking

visits to pharmacies and practices, and providing incentives for GPs to engage with MUR. The seven PCOs that included MUR and community pharmacy in their medicines review strategy undertook an average of 3.7 activities to support roll out versus an overall average of 2.7 for our sample.

Encouraging roll-out among community pharmacy contractors and GP

PCO respondents were asked what actions their PCOs had taken to encourage the roll-out of MURs among community pharmacists and GPs. Table 3 shows the actions taken and compares the frequency of use in relation to community pharmacists and GPs.

Twenty-four respondents (92 per cent) reported that their PCO had used newsletters or other forms of publicity to encourage the roll-out among community pharmacists, 14 (54 per cent) had used an event or meeting and 11 (42 per cent) had used pharmacy visits. All three PCOs that were NPC Community Pharmacy Framework Collaborative sites reported using this to focus on MUR. Four PCOs described “other” methods including giving “direct verbal advice” to contractors, organising an “area managers meeting” and “producing a protocol and patient group target list”. None of our PCOs reported introducing an incentive to encourage the roll-out of MUR with community pharmacy contractors.

Three respondents reported that their PCOs had done nothing to encourage roll-out among community pharmacists.

Twenty-one respondents (72 per cent) reported that their PCO had used newsletters or other forms of publicity to encourage the roll-out among GPs, 17 (59 per cent) had used practice visits and eight (28 per cent) had held an event or meeting with GPs. Two of the three PCOs that were NPC Community Pharmacy Framework Collaborative sites had used this as an opportunity to focus on MUR with their GPs. Six PCOs reported using “other” methods including “practice managers meetings”, “local medical committee meetings”, “included as Quality and Outcomes Framework target” and “resource packs for GP practices given to local pharmacists to take into GP practice meetings to describe MUR”.

One PCO said it had introduced incentives for GPs to encourage roll-out. Three PCOs reported doing nothing to encourage roll-out among GPs.

PCOs were less likely to have organised an event or meeting for GPs than for community pharmacists. PCO visits to GPs were more common than visits to pharmacies.

Involving patients in the roll-out of MUR

PCO respondents were asked to describe how they had involved patients, if at all, in the roll-out of MUR. Few had done so.

Where it had occurred it was through a mixture of meetings and briefings with lay members, and leaflets aimed at the public about MURs.

One PCO said that, since only 50 per cent of pharmacies in the PCO were accredited, it had to be careful to balance informing patients and managing public expectation.

Evaluating the impact of MUR

Four PCOs (15 per cent) reported that they had undertaken work to evaluate the impact of MUR. The methods described were informal and often opportunistic, for example, reviewing completed MUR forms either on monitoring visits or through practice-based prescribing team members, spontaneous feedback from GPs who had received MUR forms and collecting and reviewing a random sample of MUR forms.

SHA and PCO perspectives on MUR

In this section we have integrated the SHA interview data with the qualitatively analysed responses to the open questions in the PCO survey. MUR was generally perceived to have considerable potential but to have been problematic in its implementation. Respondents said that the service had not taken off in the way that had been expected:

There has not been the uptake of advanced services that was expected. (SHA13)

Take up of MURs has been poor with nowhere near the target being reached. (SHA23)

MURs are poor at the moment. (PCO4)

One issue was a lack of clarity about what constituted an MUR. One respondent talked about local experience of a PCT providing feedback to pharmacists where the outputs of MURs were less focused on practical issues to do with medicines use:

We have trained the pharmacists but they still make clinical recommendations, despite being asked not to do this. We give (them) feedback but many just don’t seem to understand what the point of a MUR is. (PCO29)

The confusion among pharmacists about the boundary between MUR and clinical medication review was also noted to have an effect on GPs. Other respondents commented on the lack of familiarity of GPs with the purpose of the MUR service and about what sorts of issues an MUR report might encompass:

What is an MUR? What is not? There is a lot of confusion in pharmacy and general practice. (SHA14)

(Need) national publicity on what constitutes a good MUR. (PCO17)

Some SHA respondents referred to the positive impact of MURs on local relationships between community pharmacies and practices:

MURs have allowed pharmacists to link up with practices and find out what information practices require. (SHA2)

Professional relationships have improved and MURs are happening. (SHA15)

These comments were made in the context of specific PCOs where MUR implementation was reported to have gone well. Others, however, cited inter-professional relationships as problematic:

No PCT has cracked the problem of community pharmacist/GP communication. (SHA3)

No thought was given to the reliance on GPs to enable repeat dispensing and action MUR findings — no funding available to ensure GP co-operation. (PCO10)

Several respondents made reference to the differing responses of GPs when receiving MUR reports:

(Public perception and) GP acceptance of MUR is poor. (PCO21)

This was exemplified by the comment from one respondent, who attributed it to the nature of the information contained in the report sent by the pharmacist to the doctor:

The information provided (by the community pharmacist) is either too clinical or too basic and this has antagonised GPs. (SHA2)

There were few positive examples from either SHAs or PCOs around MUR implementation. One respondent reported good progress in a PCO that had actively involved local GPs in developing MURs:

Has worked well in some areas eg (PCT A), where the GPs have set the patient selection criteria. (SHA12)

A different issue was a perceived lack of ownership by PCOs of advanced services. The funding and specification for these services are agreed nationally. Arrangements for accreditation for MURs comprised university assessment against a competence framework and premises requirements in terms of consultation facilities. The extent to which PCOs felt able to influence or manage the MUR service locally was questioned by some respondents:

As accreditation is provided externally (non-NHS) PCTs feel disconnected from the service and are unable to assess what is occurring. (SHA15)

There are concerns (among PCTs) around the training, (about) a lack of confidence of many pharmacists and (about) receipt of the service by GPs. (SHA18)

Lack of facility for effective control in management of MURs. (PCO31)

A key issue was the lack of transparency about what outcomes were being achieved from MURs. In this respect it was suggested that it was currently impossible for PCTs to make any such assessment:

MURs have given problems because they are uncontrolled. PCTs have been challenged to decide how MURs are improving patient care and giving value for money. (SHA3)

(What are) the quality and usefulness of MURs? Currently PCT staff cannot view completed paperwork in pharmacies. In order to monitor the quality of MURs this needs amending. (PCO6)

Some respondents were concerned that the annual cap on numbers of MURs provided by individual pharmacies had, in practice, been perceived as a target, with numbers of MURs provided becoming the main measure by which the service was assessed:

There’s no quality monitoring. Should PCTs be aiming for quality or quantity? (SHA15)

When respondents did feel able to speak about the quality of MURs being conducted the emphasis was negative:

There is a frustration about community pharmacists making recommendations that are wrong. (SHA16)

The policy of some pharmacy multiples to set numerical targets for their pharmacists’ MURs was thought to have potential effects on the quality of reviews:

Output from some pharmacists is of variable quality owing to a push by some multiples to do as many as possible. This reflects badly on community pharmacy services in general and in relation to practice based commissioning in particular. (SHA12)

Another respondent mentioned the effects of multiples’ policies:

Results from MURs have wound up the GPs, especially those from some multiple pharmacies who have been forcing employee pharmacists to do 250 MURs, often of questionable need and dubious quality. (SHA18)

A key process issue was the documentation required for MURs and here there were two concerns: first, the record itself was overcomplicated and, secondly, because it was not possible technically to transmit confidential information from the pharmacy to the surgery in electronic form some practices refused to deal with reports:

Paperwork is dreadful and not available electronically. (SHA2)

Too complicated and GPs don’t know what to do with it. It’s a problem in paperless practices as all the pages can’t be scanned in. (SHA12)

There was a general perception that GPs were unlikely to become engaged with MURs because the structure of the general medical services contract had led to an expectation that payment would be required for any activity that was perceived as new. Several respondents suggested that GPs needed to receive incentives to take action when they received a MUR report:

Link them (MURs) with the GMS QOF so the GP must do something about the MUR report. (SHA2)

Need GMS contract to reflect requirements of pharmacy contract, eg, MUR. (PCO13)

Indeed one PCO was reported to have started local discussions on this subject:

(PCOB) have discussed MURs and a link with the GMS contract with the LMC. (SHA17)

Overall many respondents, although not negative about the concept of MURs, remained to be convinced that the service could deliver. Data to confirm the value of the service were thought to be essential in justifying its future:

Has potential but must be seen to be cost-effective and provide a positive outcome for patients. (SHA10)

Need national guidance on requirements for comprehensive monitoring of MURs. (PCO31)

A SHA/national evaluation is required to assess outcomes and link it into long term conditions and thus PBC. (SHA17)

Discussion

This is the first study to correlate data on actual volume of MUR provision with local and national perspectives on implementation. At the end of the first year of the new pharmacy contract, PCO and SHA stakeholders perceived MUR as a service that was not yet fulfilling its potential. The data on provision of MURs in the sample PCOs support stakeholders’ accounts and show that the volume represented only a small percentage, 6.81 per cent, of allocated budget. This level of provision reflects the national data6 where 152,854 MURs were provided over the same period in England and Wales, 7.31 per cent of a possible 2,088,200 (if all 10,441 community pharmacies in Enland and Wales at 31 March 2005 carried out the maximum of 200 MURs each). The mean number of MURs was 484 per PCO nationally compared with 471 in the PCOs in our sample.7 Across our sample PCOs, 38 per cent of pharmacies had claimed MUR payments, compared with a figure of 31 per cent from a national survey of PCOs8 and 39.1 per cent from national statistics.6 The average number of MURs per providing pharmacy in our sample was 35.7 compared with 37 for England and Wales.6

We found a 32-fold difference in MURs per million prescriptions dispensed across our PCOs and a 33-fold difference in the number of MURs per 1,000 population. However it should be noted that no breakdown is available of patient registrations with dispensing doctors or prescriptions dispensed by these practices so, although the analysis shows wide variation, some caution is needed in interpretation for specific PCTs. MUR is not available to patients registered with dispensing doctors and this itself creates inequity in provision.

Nationally the number of pharmacies claiming monthly payments for providing MURs in England rose from 2,081 (20 per cent) in January 2006 to 2,953 in May 2006 and 4,107 in November, representing 42 per cent of the community pharmacies in England and Wales.7 Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC) figures7 show that the monthly total number of MURs for England remained steady between April and September then rose by around 20,000 in October and 22,000 in November. Eight months into the second year of the service the number of MURs provided represented around 8 per cent of those for which funding are available (Table 4).

There were wide variations in levels of provision between the PCOs in our sample that remained after standardising for population and prescription numbers. Variation may be largely attributable to differences in percentages of multiples in the individual PCOs. Pharmacies from multiple groups provided over 80 per cent of MURs and independent pharmacies were substantially under-represented in terms of MUR provision.

One factor that may have influenced implementation is the support provided for roll-out of the service. Most community pharmacists in a telephone interview survey in two PCOs “felt they did not receive sufficient support from the PCO”9 but no information was available about the support provided by their PCOs. The PCOs in our sample had invested different amounts and types of resource to support the local roll-out of MUR. Only three said they had done nothing to support roll-out and most reported publicising MUR using written information. Some also used local meetings and community pharmacy and general practice visits. Although we did not ask about this directly we think it likely that the GP practice visits were being made for other reasons (for example, to discuss prescribing) and that MUR was incorporated into the agenda. Two PCOs appeared to have found creative ways to incentivise GP participation through the GMS Quality and Outcomes Framework. The effects of these activities are difficult to discern since the provision of MURs was dominated by pharmacy multiples. Disentangling the effects of corporate targets on provision from the impact of local PCO support strategies was not possible because the number of MURs provided by independent pharmacies was so small. We will be analysing data from the second year of the MUR service in mid-2007 when the numbers will be larger, and intend to use regression analysis to investigate this further.

Another reason why implementation of the MUR service has been slow is the evidence of a substantial gap between the number of pharmacists accredited to provide MURs and the number of pharmacies claiming MUR payments. A questionnaire survey of 140 community pharmacists found that 59 per cent of respondents were accredited to provide MURs but only 52 per cent of these were doing so, and that overall only 38 per cent of the pharmacies had a consultation room.10 Data published by the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee showed that 13,157 pharmacists were accredited by November 2006. However the number of pharmacies claiming payment in England at November 2006 was 4,107.7 These data indicate two barriers: one relating to suitability of premises and one relating to accredited pharmacists not taking the next step into provision.

Just over half of the PCOs had a strategy for medicines review. These tended to focus on GP practice-based clinicians (including pharmacists), with community pharmacists featuring less often. Overall only one in three of our sample PCOs both had a strategy and included MUR within it. This suggests that PCOs may not yet have been able to think strategically about MUR and how it could support their local priorities. However almost all of the PCOs had identified target patient groups for MUR, with respiratory conditions the most frequently cited.

PCO and SHA respondents generally viewed MURs as a less successful feature of the new contract. Although there were some areas where the service appeared to have developed well, this was the exception not the norm.

Although the level of MUR provision was below the expectations of the national contract team, the pattern of take up is perhaps not surprising. MUR is an innovation and previous research in community pharmacy has demonstrated the challenges required to embed and sustain it.2,11

In considering possible barriers to the provision of MURs it is noteworthy that both PCOs and potential MUR providers had other aspects of contract implementation that were “must dos” in the first year of the new contract. The demands of contract implementation are likely to have fallen more heavily on independent contractors, who have no corporate systems and economies of scale to share the work needed. Multiples, on the other hand, have well established management systems that might be expected to streamline paperwork and reduce the effort required at individual pharmacy level to design, for example, standard operating procedures or new data-recording policies for essential services. These efficiencies might also be expected to apply in relation to advanced services.

Stakeholder accounts identified that inter-professional relationships between community pharmacists and general practitioners were acting as a barrier to MURs in many cases. Elvey and colleagues reported that “lack of support from GPs” was the barrier to contract implemenation most frequently cited by PCO respondents in their survey.8 A questionnaire survey of community pharmacists also identified “the GP response to the MUR service” as a key barrier.10 Our PCO survey found low levels of contact between local pharmaceutical and medical committees, suggesting that dialogue was limited. Although committee level contact is not the only way in which local discussions might occur, it may be an important marker. It will be difficult for MUR to flourish in the future without improvement in the local relationships between community pharmacy and general practice. Stakeholders thought that GPs might not know the purpose of an MUR and, although MUR is primarily intended to identify and address practical issues in medicines use, there are times when the pharmacist might need to make suggestions for changes. Here, stakeholders thought that GPs perceive any action required from them by an MUR as new work and expected that they should be paid for it.

The format of the documentation of MURs was thought by both PCO and SHA respondents to be complex and difficult for GPs to use. Some respondents commented that until it was possible to transmit the information electronically many practices would not use it, particularly those that were paperless.

Both SHA and PCO respondents were concerned that the quality and value for money of MURs could not yet be demonstrated since PCOs did not have the right to audit MUR reports. This lack of data was thought to have disenfranchised PCOs and meant greater scepticism about quality and the potential contribution of MURs to patient care. Four of the PCOs in our sample reported undertaking some sort of evaluation of MURs using ad hoc methods. So far we are aware, only one other PCO has publicly reported establishing a system for feedback on MURs,12 with those involved saying “we have been impressed by the quality and outcomes”. In contrast “anecdotal feedback suggests that there is considerable variation in the quality of referral forms sent to GPs following a MUR”.13

Respondents from PCOs and SHAs suggested a number of ways to improve implementation of the MUR service including a clearer definition of what was and was not an MUR, linking MURs to the QOF in the GMS contract, revising the paperwork and introducing audit.

The recent financial settlement for the contract for 2006–07 included an increase in the maximum number of MURs for which payment can be claimed from 250 to 400.14 Data on levels of provision in 2006–07 together with our findings indicate that further action is needed to address potential barriers, and to learn from local experience of facilitating factors.

Our study has some strengths and limitations. A strength is that it correllates data on MUR volume with data from PCO and SHA perspectives. The high response rates from both PCOs and SHAs mean that the possibility of bias is reduced. The PCOs included were of wide sociodemographic variation and with respect to participation in NHS initiatives, the sample was representative of the national population of PCOs. Our study has not explored the content, appropriateness or outcomes of medicines use review so we cannot say in what way medicines use reviews are addressing the needs of patients, the NHS and health care professionals.

Conclusions

The numbers of MURs provided in the first year of the new community pharmacy contract were substantially lower than expected. Multiples were responsible for over three quarters of MURs conducted; independents were under-represented. Stakeholders identified a number of barriers to provision. These findings suggest that further action is needed to support and embed the MUR service.

Key findings

- Uptake and spread of the MUR service in its first year accounted for 7 per cent of the allocated funding, with one in three pharmacies participating

- There are wide variations in provision in different parts of England and Wales

- Independent pharmacies were under-represented in the MUR service in its first year

- NHS stakeholders identified a number of barriers to provision and asked for an audit of value for money from MURs

- At the halfway stage in the current NHS year the provision represents 6 per cent of allocated funding

- Further action is now urgently needed to support and embed the MUR service

Acknowldegements

The study was funded by the Pharmacy Practice Research Trust as part of the national evaluation of the community pharmacy contract for England and Wales. We are grateful to the Prescription Pricing Division of the NHS Business Services Authority for their assistance. We would like to thank the study participants from primary care trusts, local health boards and strategic health authorities. We are grateful to our external advisory board for its advice and to Robert Hallworth who conducted the SHA interviews.

This paper was accepted for publication on 5 February 2007.

About the authors

Alison Blenkinsopp, PhD, FRPharmS, is professor of the practice of pharmacy in the department of medicines management at Keele University. Gianpiero Celino, BSc, MRPharmS, is director of Webstar Health. Christine Bond, PhD, FRPharmS, is professor of primary care pharmacy, and Jackie Inch, BPharm, MRPharmS, is research fellow in the department of general practice and primary care at the University of Aberdeen.

Correspondence to: Professor Alison Blenkinsopp,School of Pharmacy, Keele University, Keele, Staffordshire ST5 5BG (e-mail a.blenkinsopp@keele.ac.uk)

References

- Boardman H, Blenkinsopp A, Jesson J, Wilson K. A pharmacy workforce survey in the West Midlands (2). Changes made and planned for the future. Pharmaceutical Journal 2000;264:105–8.

- Bond CM, Laing AW, Inch J, Grant A. Evolution and change in community pharmacy. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society; 2002.

- The Pharmaceutical Services (Advanced and Enhanced Services) (England) Directions 2005. London: Department of Health; 2005.

- Celino G, Blenkinsopp A. Local commissioning of community pharmacy services in England prior to the introduction of the new pharmacy contract. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2006;14(Suppl 2):B30.

- Ritchie J, Spencer E. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess RG (editors). Analyzing qualitative data. London: Routledge; 1994.

- General Pharmaceutical Services in England and Wales 1996–7 to 2005–6. London: Department of Health; 2006.

- Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. MUR statistics. Aylesbury: PSNC; 2006.

- Elvey R, Bradley F, Ashcroft D, Noyce P. Implementing medication usage reviews through the new community pharmacy contract: key drivers and barriers. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2006:14(Suppl 2):B32.

- Hall J, Smith I. Barriers to medicines use reviews: comparing the views of pharmacists and PCTs. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2006:14(Suppl 2):B51.

- Ewen D, Ingram MJ, MacAdam A. The uptake and perceptions of the medicines use review service by community pharmacists in England and Wales. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2006:14(Suppl 2):B61.

- Tann J, Blenkinsopp A. Innovation in community pharmacy: accelerating the spread of change. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society; 2004.

- Goldstein R, Riley G, Jenkins R. Medicines use reviews — need to reconsider “10 minute campaign”. Pharmaceutical Journal 2006;276:415.

- James DH, Hatten S, Roberts D. The development of quality indicators for evaluating pharmacists’ referral skills following a medicines use review (MUR). International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2006:14(Suppl 2):B31.

- Community Pharmacy News. Aylesbury: Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee; September 2006.