Abstract

Aim

To determine the accessibility of over-the-counter (OTC) laxatives in a defined geographical area in the UK and to investigate pharmacists’ and other retailers’ awareness of and response to misuse of laxatives in the context of eating disorders.

Design

A confidential questionnaire survey.

Subjects and setting

293 potential laxative retailers in the area local to a community-based specialist outpatient service for adults with eating disorders.

Outcome measures

Number and types of stores stocking laxative products; prevalence and nature of standardised and specific sales policies for laxatives; awareness of laxative misuse associated with eating disorders; retailers’ response to suspected misuse; the potential for collaboration between laxative retailers and eating disorder services in addressing the issue of laxative misuse.

Results

53 retailers (18.1%) returned questionnaires. Laxatives are widely and easily available through community retailers; measures to regulate purchases are variable; and responses to suspected misuse are usually in the form of restricting sales, rather than offering guidance.

Conclusions

The majority of retailers agree they have an important role to play in addressing misuse and are willing to collaborate with eating disorder services. However, retailers need more information and resources to enable them to inform, advise and help suspected misusers.

Yesterday I was once again discharged from hospital after excessively abusing laxatives for the past three years. . . . I have been taking these tablets to the excess of 100 a day. This was not usually a problem, as many chemists would sell them to me repeatedly every day. . . . Last year I weighed four stone and looked near death, and very rarely did a pharmacist question me. . . . I got to know the chemists that would feed my habit without hesitance and became confident about purchasing tablets from them. . . . These pharmacies should surely take some responsibility and I would like to see some action taken to prevent the easy purchasing power of these dangerous drugs” — Letter to the Royal Pharmaceutical Society1

Serious laxative misuse has been associated with gastrointestinal tract dysfunctions, electrolyte imbalances, kidney disease and cardiovascular disorders.2 However, despite the severe consequences of their misuse, in the UK, laxatives of various types are currently available without prescription. Studies of laxative misuse in the general population have reported prevalence figures ranging from 2.0 per cent in secondary school pupils3 to 12.8 per cent in UK college students,4 and rates are substantially increased in eating disorder populations. Turner et al report laxative misuse in as many as 32 per cent of anorexic adolescents,5 and figures of up to 75 per cent have been reported within bulimic populations.6

Specification 10 of the Code of Ethics and Standards of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society states that “pharmacists and their staff must be aware of the abuse potential of certain OTC products and should not supply where there are reasonable grounds for suspecting misuse” (p91). Laxatives are listed in the Society’s practice guidelines as potential substances of misuse (p109).7

A number of general surveys have investigated pharmacists’ perceptions of the misuse and abuse of various OTC medicines (including laxatives) and the measures taken to manage or prevent suspected misuse.8–11 Findings suggest that although there is a reasonable level of awareness of the problem, with a number of community pharmacies taking steps to address the risk, the policies across different pharmacies are variable,8 and many are non-specific10 and appear to offer little long-term resolution of the misuse problem.11

Imposing restrictions on the sales of laxatives is unlikely to prevent eating-disordered individuals from obtaining and misusing laxatives. However, pharmacists can play an important part in the detection and prevention of misuse,12 beyond merely regulating sales of OTC medicines: government policy is seeking to give pharmacists increasing responsibility in providing advice and support for customers, as a first port of call before seeking GP consultation.13 Current research literature also highlights the potential role of the pharmacist as an interface between client and treatment, and the possibility of considering inappropriate medicine requests as opportunities to inform, advise and help suspected misusers.11 Pilot work to involve pharmacists in client treatment and support has begun,14 and there is scope to investigate further how laxative retailers might be encouraged and enabled to support the work of eating disorder services, for example, in providing information about the side effects of laxatives or in directing customers to appropriate treatment services.

To date, surveys of pharmacists have not, to our knowledge, focused exclusively on sales policies for laxatives or addressed the issue of their misuse specifically in relation to eating disorders. Nor have risk awareness and sales policies in non-pharmacy retail outlets (such as alternative health shops, supermarkets, or newsagents) been assessed. The present study therefore sought to determine the availability of OTC laxatives in the area local to an adult community-based eating disorder service, and to investigate the prevalence and nature of standardised and specific policies on sales of laxatives. It also explored retailers’ awareness of the issue of laxative abuse in the context of eating disorders, and the potential for establishing retail outlets as sources of information and support and as links to treatment services for laxative misusers.

Method

A questionnaire was compiled on the basis of forms used in previous pharmacy surveys, and adapted for all potential laxative retailers, including:

- Category A: dispensing pharmacies, including supermarket dispensaries

- Category B: non-dispensing health and beauty/drug stores, and supermarkets with health and beauty sections

- Category C: alternative/complementary health stores

- Category D: convenience stores, newsagents and service stations

A draft version of the questionnaire was piloted in seven retail outlets located in a neighbouring town (three from category A, three from B and one from C). The final version of the questionnaire (available on request from the first author) was then sent to a total of 293 local retailers within a defined geographical area (72 to category A, 29 to B, 15 to C, 175 to D; and two to “other” retailers (discount store/not stated). These retailers were identified using the relevant pharmacy registers and local telephone directories. The questionnaire was accompanied by a covering letter (addressed to the manager), an information sheet, and a reply-paid envelope. Retailers were asked to return the questionnaire within two weeks, after which time a reminder letter was sent to all retailers. Questionnaires were completed anonymously.

Results

Return rates

A total of 53 retailers returned their questionnaires (18.1 per cent). The response rate was highest for pharmacies (23.6 per cent) and there was no response from alternative/complementary health stores. Eight questionnaires were “returned to sender” because the address was no longer valid. A total of 20 retailers, (37.7 per cent of respondents) reported that they sold laxative products: all 17 pharmacies (category A) that returned the questionnaire stocked laxatives, as did two of the three health and beauty store respondents (category B). However, laxatives were available from only one of the 31 category D respondents. One pharmacy only completed p1 of the questionnaire, stating: “We have our own procedures and protocols and do not wish to participate in further work.” The following results therefore apply to those stores that stocked laxative products and completed the questionnaire in full (n=19, including 16 pharmacies; in some cases specific questions were not completed). In the results presented below, percentages refer to the proportion endorsing a particular response out of the total number of completed responses to that specific question and are presented as a percentage (N/total) — eg, 50 per cent (9/18).

The most widely available laxative brands were stimulant laxatives: Senokot, DulcoLax and Ex-Lax, respectively. Califig (stimulant), Fybogel (bulk forming), and Lactulose (osmotic) were also commonly stocked. Retailers stocked between one and 24 products, with the average number per store being approximately 12. Most products were displayed on open shelves. Products which retailers thought were most likely to be misused were senna preparations, followed by DulcoLax, Nylax, Ex-Lax and liquid paraffin.

Awareness of issue

Retailers were asked to indicate on an 11-point Likert-scale (0–10) how aware they were before receiving the questionnaire of the issue of laxative misuse in the context of eating disorders. The mean score for dispensing pharmacies (n=16) was 9.0 (“very aware”), with individual scores ranging from 6 (“reasonably aware”) to 10 (“very aware”). The two category B stores indicated their levels of awareness as “not at all aware” (score=0), and (for a supermarket) “very aware” (score=9). The category D store indicated only slight awareness (score=3).

Seven retailers believed that the issue of laxative misuse in the context of eating disorders was certainly of relevance in their stores; a further nine retailers thought it was an issue to some extent. Two pharmacies thought it was not an issue at all, and one (category D) respondent was unsure. Reasons given as to why it might not be (much of) an issue were: because sales of laxatives were low (four) (“at the moment slimming preparations are more available”); because staff did not suspect any customers of misusing laxatives in the context of an eating disorder (two) (“[we are] dealing with a small community — mostly elderly people”); because steps were taken to deal with the problem (two) (“[we] keep [laxatives] for supervised sales only”;“[we] counsel patients to suggest diet rather than sell any products”); or because laxatives were not prescription medicines (one).

Sales policies and procedures

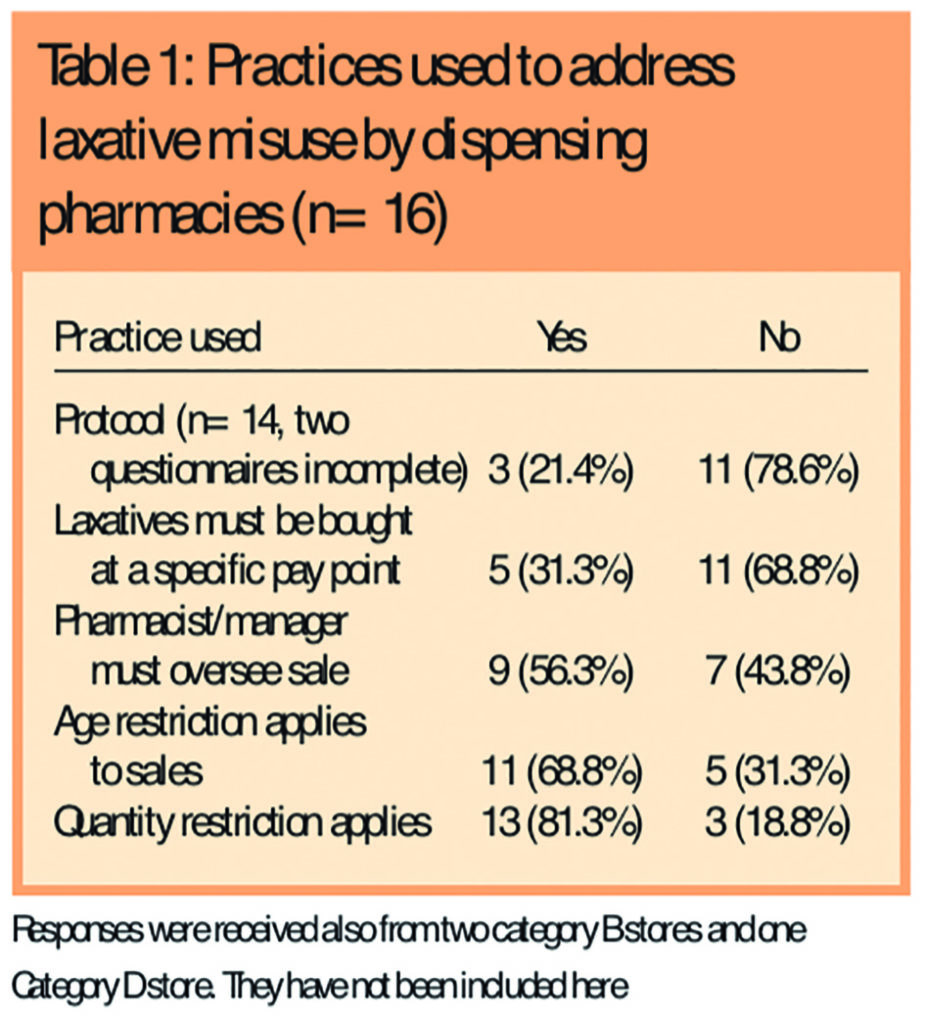

Only three (dispensing pharmacy) stores selling laxatives had a store protocol (ie, written procedures for staff to follow when supplying laxatives) (Table 1).

Six stores said there was “no particular reason” why they did not use a store protocol, and one respondent said they had “no idea” why there was no protocol. Other responses explained that a protocol was “too bureaucratic and time consuming” (one), that it had been “overlooked by [the] pharmacy department at head office” (one), that “it [had] never been raised as an issue before” (one), and that “the store was in the process of writing a protocol” (one).

However, 94.7 per cent of retailers (18/19) did have at least one standard practice in place (not necessarily written) to limit or monitor sales of laxatives. The remaining (category B) retailer justified the lack of standard practices by the fact that its sales of laxatives were “very low”. The practices used to address laxative misuse by dispensing pharmacies are given in Table 1 and details of the three protocols mentioned are given in Panel 1.

Panel 1: Details of protocols

Protocol 1

- Protocol applies to health care assistants.

- Customer should be asked whether they have used the product before

- The pharmacist must oversee sales to young children and the elderly, and sales of large quantities

- The product can be given when it is “for occasional use”

Protocol 2

- Protocol applies to the pharmacist

- The pharmacist must oversee the sale if the customer is pregnant, elderly, young, or using other medicines

Protocol 3

- Protocol applies to all staff

- Customer should be asked: Who is it for? What symptoms do they have? How long have they had the symptoms? Have they tried anything for the symptoms yet? Do they take any other medication? Have they used laxatives before?

- The pharmacist must oversee the sale if the customer is requesting a large quantity of laxatives or if the customer is buying them regularly

The most common standard practice was an age restriction on sales of laxatives (68.4 per cent of stores; 13/19), often in the form of alerting the pharmacist or manager to these customers. However the target age ranged from 14 to 18 years. Other retailers were concerned with very young children (one) or the elderly (one). Practices to limit quantity (eg, alerting the pharmacist) were also common (68.4 per cent; 13/19) but, again, these applied variably, eg, on more than one packet (five), or on “large quantities” (one). Rarely did laxatives need to be purchased at a specific till in the store (26.3 per cent; 5/19), and usually only in the case of behind-the-counter products. Sales were usually only overseen by the pharmacist or manager (47.4 per cent; 9/19) in the case of large quantities (two), or pharmacy-only/behind-the-counter products (four).

In 15 stores (93.8 per cent; 15/16), the implementation of standard practices was overseen by the head pharmacist or store manager and in three stores implementation was also the remit of the area manager or head office. However, in one category B store, implementation was the responsibility only of general sales staff.

Most retailers (62.5 per cent; 10/16) drew on their professional expertise to inform practice: this was usually supplemented by advice from other sources, although in four cases standard practices were informed by professional expertise alone. Six retailers received guidance from head office (37.5 per cent; 6/16); seven retailers (43.8 per cent; 7/16) referred to published guidelines; however, only two stores (12.5 per cent; 2/16) used government policy to guide their practices. One (category B) store received no guidance at all. Some 73.3 per cent of respondents (11/15) thought they had adequate guidance. Of the four retailers who found the guidance they received inadequate, three relied only on professional expertise or published guidelines, and one received no guidance at all.

Retailers were asked to rate on an 11-point Likert-scale (0–10) how effective they believed their retail practices (to limit or monitor sales) were in discouraging misuse. The majority of retailers (60.0 per cent; 9/15) felt their practices were “reasonably” effective, 20.0 per cent (3/15) thought they were “very effective”, 6.67 per cent (1/15) thought they were “slightly effective”. No retailer believed them to be entirely ineffective. However, two retailers (13.3 per cent; 2/15) were unsure as to the efficacy of their sales practices.

Identifying cases of misuse

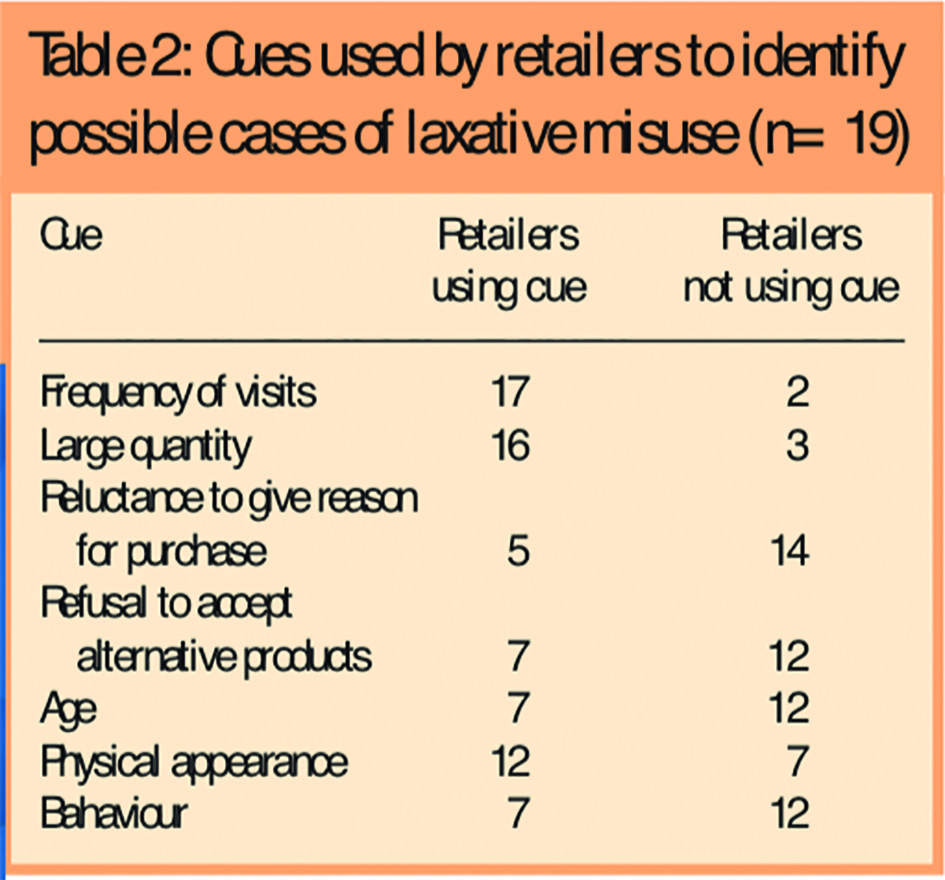

The most common cues retailers used to identify possible cases of laxative misuse were the frequency of visits by the customer (89.5 per cent of retailers; 17/19) and the purchase of large quantities (84.2 per cent; 16/19) (Table 2).

A majority (63.2 per cent; 12/19) would also be alerted by the customer’s physical appearance. Fewer retailers responded to the customer’s age (36.8 per cent; 7/19), behaviour (36.8 per cent; 7/19), refusal to accept alternative products (36.8 per cent; 7/19) or reluctance to give reasons for purchase (26.3 per cent; 5/19). Almost all retailers (94.7 per cent; 18/19) paid attention to more than one cue.

In terms of physical appearance, 10 retailers were particularly vigilant with regards to low-weight customers: “very thin, baggy clothes”, “thin/gaunt”. One retailer also stated that he would be concerned in the case of an over-weight customer.

Other physical characteristics included: a guilty appearance (one); young and female (one); having other physical symptoms, eg, piles (one) or “skin marks” (one); and being well-dressed (one).

When asked to give details of customers’ behavioural characteristics, three retailers described either a forceful or demanding style (“aggressive and ready to pay any price”, “confident — adamant to have product”), and four described an edgy or avoidant style (“slightly nervous or ambiguous about symptoms or questions”, “withdrawn and reluctant to answer questions”).

Response to suspected misuse

When presented with someone suspected of misuse, the most common response was to refer the request to the (head) pharmacist or store manager (88.2 per cent of retailers; 15/17). Other common responses were: enquiring into the reasons for purchase (52.9 per cent; 9/17); enquiring about previous treatment attempts (52.9 per cent; 9/17); and (after some initial enquiry or consultation) referring the customer to their GP (52.9 per cent; 9/17). However, only about one third of retailers (35.3 per cent; 6/17) would suggest alternative products, and only 29.4 per cent (5/17) would enquire about the customer’s condition.

When asked to describe the circumstances under which a customer would be refused the sale of laxatives, responses included: if the customer was known or believed to be misusing laxatives (five) (eg, “obvious abuse”; “apparent misuse, ie, refusal to see GP about problem, refusal to accept another product”); if the customer was a frequent purchaser (seven), requested an exceptionally large amount (six) or could not give good reasons for their purchases (four); if the customer was “under-age” (three); if the customer returned after ignoring the advice of the sales staff (two), eg, “continuing purchase after recommendations to see GP”; or if the sale was not thought suitable for the patient’s health (two), eg, “anorexic”.

Less than half of retailers who sold laxatives (41.2 per cent; 7/17) stated that they would communicate with neighbouring retailers about suspected cases of use, and the majority of retailers (nine) were unsure as to how helpful such communication could be.

Information and training for staff

In 73.7 per cent of stores (14/19), staff received in-store training on the issue of laxative misuse. However, other sources of information and training were used only in a minority of stores. Training from head office, educational courses or distance learning were used to train staff in just three stores; only five stores had access to published articles and two stores received information from drug representatives. In two stores (category A and B), staff received no training about laxative misuse. Staff of just one (pharmacy) store had any information about local support services for individuals who were misusing laxatives.

Information and support for customers

Only one (pharmacy) store had information — in the form of leaflets — available to advise customers on the issue of laxative misuse. None of the stores selling laxatives had any system in place to support customers suspected of misuse.

Potential for collaboration between retailers and eating disorder services

More than two-thirds of those who sold laxatives were prepared to display posters, provide leaflets or display shelf cards on the issue of laxative misuse or eating disorders. One (pharmacy) retailer already provided such information.

Three (pharmacy) retailers (16.7 per cent; 3/18) were already offering customers face-to-face advice about laxative misuse, and four (22.2 per cent; 4/18) were already offering advice about eating disorders. A further 11 retailers (61.1 per cent; 11/18) would be prepared to offer such face-to-face advice.

Retailers (n=19) were asked to rate on an 11-point Likert scale (0–10) the extent to which they agreed with various statements relating to laxative sales and the issue of laxative misuse. Responses were varied, but most respondents (17) agreed (“somewhat” or “strongly”) that retailers had an important role to play in addressing the issue of laxative misuse (mean = 8.0, range = 3–10). However, over half agreed that they needed more guidance to identify cases of misuse (10) (mean = 6.31; range = 1–10) and to manage such cases (12) (mean = 6.68; range = 3–10).

Although 70.6 per cent of respondents (12/17) said they would be willing to work with eating disorder services in addressing the issue of laxative misuse, currently, none of the retailers had any connection with such services. Among those retailers that were not willing to work with eating disorder services, reasons given included lack of time (three) or facilities (one) (“no time, no space, no confidential area”); thinking it was not the role of a non-pharmacist (one); thinking it was too much work without sufficient gain (one) (“no benefit to store profit”); and company policy (one).

Discussion

The present study investigated the availability and accessibility of OTC laxatives in an area of the UK and explored the policies and practices which retailers, of various types, use to address laxative misuse. The survey also addressed retailers’ awareness of the issue of laxative abuse in the context of eating disorders, and the potential for establishing retail outlets as sources of information and support, and as links to treatment services, for individuals misusing laxatives for weight and shape purposes. The results provide insight into the misuse issue from the perspective of the retailer, valuably supplementing clinical perspectives. This insight also provides the opportunity to develop early-intervention schemes that address laxative misuse at the point of purchase.

Before discussing the study findings, it is necessary to acknowledge that the study was severely hampered by the low return rate of questionnaires. There may have been various reasons for the poor response. Some questionnaires, in addition to those noted, may have been invalidly addressed. Many retailers who received a questionnaire may not have stocked laxatives and therefore may not have been interested in participating (despite a clear statement in the information letter and on the questionnaire that their response would still be of use). Retailers may have seen the questionnaire as judgemental and have felt uncomfortable answering its questions, and have been unable to complete it due to time constraints, especially given its relatively long and complex format. Return rates, for future surveys, might be improved by: shortening and simplifying the questionnaire; “pre-screening” retailers (eg, by a telephone call) to determine those that stocked laxatives before sending a questionnaire; and delivering questionnaires in person.

The low return rate was particularly problematic because the number of completed questionnaires per retail category was variable. In particular, no results at all were available for alternative health shops (category C), only two full questionnaires were received from retailers in category B, and only one category D store returned a full questionnaire. This made comparisons between different types of retail outlets difficult and in some cases impossible, and results reported for category B and D stores cannot justifiably be considered representative of these retailers in general. It is also worth noting that the pilot questionnaire was not trialled in category D retailers and examples of laxative products were not stated on the questionnaire; it is possible that this had implications regarding the appropriateness of the questionnaire to this particular group.

None the less, although the length and complexity of the questionnaire may have negatively influenced return rates, the returned questionnaires contained information of valuable depth and breadth. Laxatives are available in all pharmacies and also in most health and beauty stores and supermarkets (though in smaller quantities). However, they are not usually stocked in newsagents or convenience stores and, if they are, only in small quantities. The availability of laxatives via alternative health stores remains unclear. This suggests that pharmacies should be a central target of any project designed to address laxative misuse at the point of purchase. However, other types of store should not be excluded, not least given that awareness of the issue is often slight among non-pharmacy retailers.

Although most retailers believed that the issue was of relevance in their stores, sales policies and practices were informed by disparate sources, and were highly variable across stores; this is consistent with previous surveys. Additionally, since 1 January 1995, community pharmacies have been required to possess a written protocol covering the procedure to be followed when supplying a medicine.15 Although most laxatives are non-prescription products, their formal status as a substance of potential misuse makes it surprising, not to say worrying, that a protocol covering laxative sales was only available in three (pharmacy) stores, and these three were each quite different. The use of such a protocol has been strongly recommended16 and would do much to aid retailers in dealing more confidently and consistently with cases of suspected misuse. Furthermore, if practices or protocols could be formulated at a regional, or even national, level rather than at the level of individual retailers, this would address the need — clearly highlighted by the findings of the present survey — for formal standardised guidelines.

Most retailers made some attempt to address the issue of misuse. However, the steps taken were usually in the form of measures to monitor or restrict purchasing (eg, placing an age restriction on sales, or limiting the purchase quantity), rather than in the form of systems of support, education or guidance for customers. Given the wide availability of laxatives, it is unlikely that simply limiting purchases in individual stores will prevent customers from obtaining, via a number of stores, sufficient quantities to support a habit of abuse — not least because less than half of retailers would communicate with other stores in the local area about a suspected case of misuse. Thus, such practices and policies alone are unlikely to offer a long-term solution to the misuse problem.

Previous studies have instead suggested that inappropriate medicine requests might be viewed as opportunities to inform, advise and help suspected misusers11 or refer them to appropriate services. The present study suggests that there is indeed potential for such collaboration between customer and retailer: most retailers agreed that they had an important role to play in addressing misuse. Most would be prepared to display posters, leaflets, or information cards about laxative misuse and eating disorders in their stores, as well as to offer face-to-face advice to customers on these issues. It is possible that information relating to local eating disorder services, as well as national charity organisations such as the Eating Disorders Association, might be usefully displayed by similar means. It is also encouraging that a large majority of retailers would also be prepared to work collaboratively with eating disorder services.

However, at present, few retailers were actively engaged in any of these activities, despite their willingness to do so. Most retailers agreed they needed more guidance in identifying cases of misuse and in managing such cases, suggesting the reason for the lack of health promotion by retailers.

In terms of identification, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s practice guidelines only state that laxatives are misused “by anorexics” (p109).7 Not surprisingly, therefore, most retailers stated they were vigilant for clearly underweight individuals. However, laxative misuse is just as likely to occur in individuals of normal or above-normal weight.17 Providing basic information about the misuse of laxatives associated with eating disorders could therefore do much to aid retailers in identifying vulnerable customers.

In terms of management, retailers in the present survey often made prudent responses to suspected misuse (eg, exploring previous treatment attempts and reasons for the present purchase, or referring the request to the head pharmacist). However, such responses appeared limited to determining whether or not a particular sale should be made, rather than employed as ways of supporting customers and encouraging them to address their misuse problem.

This is consistent with the 2004 Which? report,18 which found that health promotion among pharmacists — eg, advising about smoking cessation, weight loss, or sexual health — was “often poor or non-existent”. Yet it is tackling the issue at this level that is likely to be most effective in discouraging misuse in the long-term. A central impediment to such an approach may be a simple lack of information: only one retailer in the present survey had any knowledge of local services for individuals who were misusing laxatives. Retailers cannot be expected to provide guidance, support and information to vulnerable customers, if they are not themselves in possession of the necessary resources.

The 2004 Which? report18 also concluded that “[the government] must invest in proper training and evaluation before putting more pressure on pharmacists or trying to extend their role”. The findings of the present study suggest that input from health services can do much to enable retailers to address laxative misuse effectively among their customers. One of the roles of primary care organisations is to improve signposting and availability of information to all retailers in their area; these organisations therefore provide one potential route for the dissemination of useful information. The findings of the present study can usefully inform such collaborations; for instance, a first step may be simply to provide retailers with up-to-date and accurate information about laxative misuse in the context of eating disorders and details of relevant local support services. In terms of addressing the issue of laxative misuse retailers, it seems, are willing and there is much that eating disorder and other services and professionals can, and must, do to ensure that they are able.

About the authors

Rachel Bryant-Waugh, DPhil, is consultant clinical psychologist and honorary senior lecturer, Hannah Turner, DClinPsych, is clinical psychologist and Philippa East, BA, is assistant psychologist at Hampshire Partnership NHS Trust Eating Disorders Service.

Correspondence to: Dr Rachel Bryant-Waugh, Hampshire Partnership NHS Trust Eating Disorders Service, Eastleigh Community Enterprise Centre, Unit 3, Barton Park, Eastleigh SO50 6RR (e-mail: rachel.bryant-waugh@ntlworld.com)

References

- Abuse of OTC medicines. Law and Ethics Bulletin: The Pharmaceutical Journal 1996;256:581.

- Neims DM, McNeill J, Giles TR, Todd F. Incidence of laxativeabuse in community and bulimic populations: a descriptive review. International Journal of Eating Disorders 1995;17:211–28.

- Kegan DM, Squires RL. Compulsive eating, dieting, stress, and hostility behaviors among college students. International Journal of Eating Disorders 1984;3:15–26.

- Clark MG, Palmer RL. Eating attitudes and neurotic symptoms in university students. British Journal of Psychiatry 1983;142:299–304.

- Turner J, Batik M, Palmer LJ, Forbes D, McDermott BM. Detection and importance of laxative use in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2000;39:378–85.

- Abraham SF, Beumont PJV. How patients describe bulimia and binge-eating. Psychological Medicine 1982;12:625–35.

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Medicines Ethics and Practice Guide. No 27. London: The Society; 2003.

- Paxton R, Chapple P. Misuse of over-the-counter medicines: A survey in one English county. The Pharmaceutical Journal 1996;256:313–15.

- Hughes GF, McElnay JC, Hughes CM, McKenna P. Abuse/misuse of non-prescription drugs. Pharmacy World and Science 1999;21:251–5.

- Pates R, McBride AJ, Li S, Ramadan R. Misuse of over-the-counter medicines: a survey of community pharmacies in a South Wales health authority. Addiction 2003;4:179–82.

- Matheson C, Bond C, Pitcairn J. Misuse of over-the-counter medicines from community pharmacies: a population survey of Scottish pharmacies. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2002;269:66–8.

- Downie G, Hind C, Kettle J. The abuse and misuse of prescribed and over-the-counter medicines. Hospital Pharmacist 2000;7:242–50.

- Department of Health. A vision for pharmacy in the new NHS. London: The Department; 2003.

- Fleming GF, McElnay JC, Hughes CM. A pilot study to investigate the identification and treatment of over-the-counter drug abuse and misuse. Health Service Research and Pharmacy Practice Conference, 19 April 2001.

- Rodgers R. PJ practice phecklist. London: The Pharmaceutical Journal; 1996. Available at www.pharmj.com/pdf/checklist/protocols.pdf (accessed 3 June 2005).

- Duggan C. Ethical dilemma: the pharmacist and laxative abuse. Chemist and Druggist 1995;243 (4 suppl 8).

- Bryant-Waugh R, Turner H, East P, Mehta R. Misuse of laxatives among adult outpatients with eating disorders: prevalence and profiles. International Journal of Eating Disorders. In press.

- The role of pharmacists is being extended. Our research shows they are not up to the job. Which? 2004;(February): 10–13.