Abstract

Awareness of menopause has increased in recent years, but there remains a lack of knowledge and education about the differences in attitudes and experiences of menopause in different ethnic groups. This article collates the available evidence to support education and care for women who are going through the menopause, focuses on the challenges that women from different ethnic groups face and outlines how pharmacy professionals can play a part in menopause care.

Keywords: menopause, peri-menopause, ethnicity, hormone replacement therapy, pharmacist

Key points

- Midlife, along with the occurrence of peri-menopause and menopause, is a crucial stage for adopting healthy lifestyle behaviours and preventive strategies for women’s health;

- There is evidence that women from different ethnic groups may cope differently with peri-menopause and menopausal symptoms, and this supports individualised care;

- It is important to recognise the potential barriers to menopause treatment that are particular to certain ethnic groups, owing to differences in perception, understanding and experience;

- There are physiological and pharmacokinetic variations between ethnic groups that can affect hormone replacement therapy, and more research is needed into these variations;

- Pharmacists play a vital role in communicating the long-term risks of menopause and the benefits of hormone replacement therapy.

Introduction

Menopause is defined by the cessation of menstruation owing to ovarian failure, and this diagnosis can be made after 12 consecutive months of amenorrhea. In the UK, on average, menopause occurs between age 45–55 years, with the average age being 51 years[1]. Menopause is preceded by peri-menopause — the transition to menopause — which can involve up to ten years of turbulent hormonal fluctuations, leading to various symptoms of varying degrees of severity. The time after menopause is termed post-menopause.

Menopausal symptoms are often not recognised in younger women but can start as early as the late 30s. One in 100 women have premature ovarian insufficiency and are aged under 40 years when menses ceases[2]. Life expectancy in women in the UK is now 82 years, which means 30% of a woman’s life is post-menopausal, on average[3].

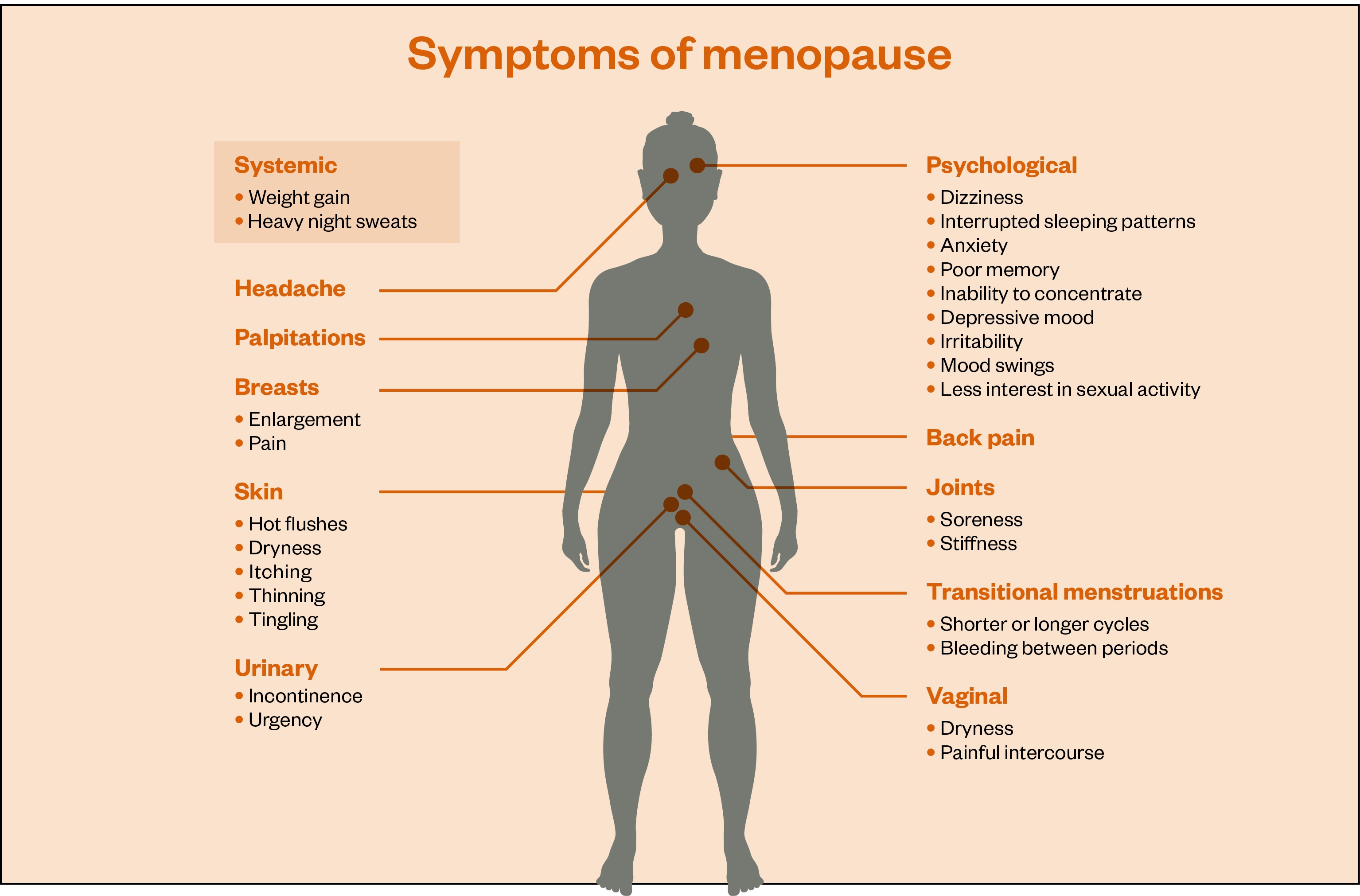

As hormone levels change throughout the transition, up to 80% of women experience symptoms related to declines in oestrogen, progesterone and testosterone[4]. There are more than 40 recorded menopausal symptoms (see Figure 1). There are oestrogen receptors all over the body and there is strong evidence to show that post-menopausal women are at increased risk of long-term effects of oestrogen deficiency, including osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity and depression (see Box 1)[5]. Evidence also shows that frequent and persistent hot flushes are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease events in later life[6]. This article will collate the evidence we have to support education and care for women who are going through the menopause, with particular focus on the challenges that women from different ethnic groups face. In an era of GP staff shortages, it will end with how pharmacy professionals can play a part in menopause care moving forward.

Box 1: How oestrogen affects different parts of the body

Brain:

- Body temperature control

- Memory

- Libido

Heart:

- Heart rate

- Healthy lining of blood vessels

- Lower cholesterol

Liver:

- Cholesterol regulation

Bones:

- Bone strength

Skin:

- Involved in collagen production

- Reduces moisture loss

Joints and muscles:

- Anti-inflammatory

- Muscle strength

- Flexibility

- Joint lubrication

Bowel:

- Maintains function

- Helps with gut microbiome

Nerves:

- Nerve transmission

Bladder:

- Reduces risk of infection

- Controls bladder function

Vagina:

- Lubrication

- Reduces bacterial overgrowth

Why is ethnicity important in menopause care?

Women from lower socioeconomic groups are around 30% less likely to be prescribed hormone replacement therapy (HRT) than those from more affluent areas[7]. The 2011 Census showed that 87% of the UK population is white and 13% is black, Asian, mixed or other ethnicity (BAME). Communities with higher BAME populations are more likely to have lower socioeconomic status[8].

In research by the Fawcett Society that included more than 4,000 women, 45% of BAME women reported that it took “many” appointments for their GP to realise they were experiencing the menopause, compared with 30% of white respondents[9].

It is vital to understand how culture and education influence the perception of menopause and potential treatment strategies in different ethnic groups. There is considerable variation in health beliefs in women from different religions and cultures. These can affect a patient’s understanding of, and willingness to follow, the recommendation of healthcare professionals[10].

There is, however, not as much evidence available as we would like, and care must be taken against over-generalising. Anecdotally, the authors can share from their practice that, for women who feel settled and culturally integrated, the difference can be less significant, as a language barrier is less likely to be a problem and there is often less reluctance to seek help.

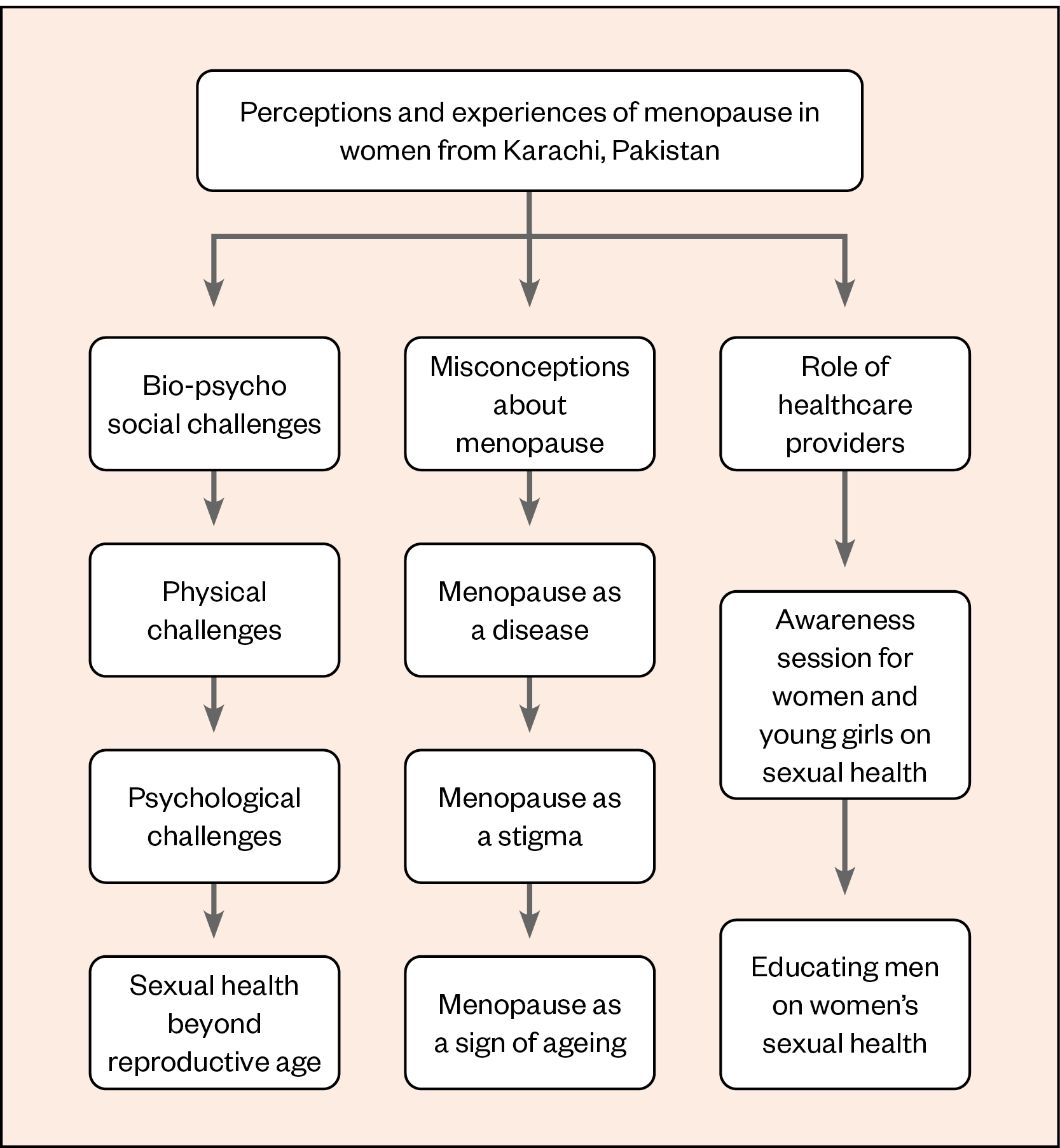

A study looking at the perceptions and experiences of menopausal women living in Karachi, Pakistan, found that the male-dominated culture meant that women lacked support from their husbands, whose attitudes and behaviour could be negative, particularly if the woman was experiencing a lack of libido[11].

When loss of libido occurs during menopause, it of course affects the relationships of patients of all ethnicities. It is also true that many BAME patients have partners who are engaged with care and supportive of menopause treatment, including HRT. However, some ethnic groups may have cultural beliefs and practices that present a barrier.

Lack of libido is a common menopause symptom in South Asian countries, including Pakistan, India and Saudi Arabia, and husbands sometimes threaten to remarry or resort to violence[11]. One woman in the Karachi study was quoted as saying:

“I believe that the topic of menopause should be addressed to create awareness. Most women in our society don’t know about basic things so it is very necessary to let them know.”

There is considerable stigma and women do not feel comfortable discussing such personal issues. Another woman in the same study said:

“My husband became agitated and frustrated with me, conflicts were very common at that time. He used to complain that I am not giving him time.”

The study of the menopause perceptions and experiences of women in Karachi, Pakistan found three main themes: bio-psycho-social challenges; misconceptions about the menopause; and the role of healthcare providers[11]. These are illustrated in Figure 2[11]. Women described some positive but mostly negative experiences of menopause, most relating to bio-psycho-social changes. Women’s negative experiences of menopause were intensified by mental distress, lack of support from an intimate partner and misperceptions about menopause[11].

Ethnicity or education

Metabolic syndrome is a collection of biochemical and physiological abnormalities associated with the development of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The abnormalities include obesity, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and impaired glucose metabolism[12]. Women tend to develop cardiovascular disease later in life, but the onset of menopause causes a steep rise in women over the age of 50 years[13].

A 2015 US study that used the data of more than 14,000 women from the Women’s Health Initiative found that, in overweight and obese women with <1 metabolic abnormality, ethnicity did not influence the risk of cardiovascular disease[12]. However, in black overweight women, having more than one metabolic abnormality did seem to increase cardiovascular risk[12].

The menopause transition is also associated with changes in body composition, lipid concentrations and carbohydrate metabolism, which, along with vascular change, progressively increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and the severity of menopause symptoms[5,13]. Genetics-based ethnic differences in insulin sensitivity and body mass index have been reported[14]. The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) found that 13% of peri-menopausal women developed metabolic syndrome during a 5-year follow up and that education, rather than ethnicity, was an independent predictor of risk[6]. This points to midlife being a crucial stage for adopting healthy behaviours and preventive strategies[13].

For women in communities where integration into UK society has not been widely encouraged, cultural differences and attitudes may have a bigger impact. Language barriers, lack of discussion/understanding and limited resources may be the greatest factors affecting their health, including during menopause. Some ethnic minority groups have been identified as having low or inadequate health literacy levels. Women may rely on translation by a family member, whose translation may well be affected by their own opinions and health literacy level[15].

Evidence to validate the variation in experience of menopause

A study comparing menopause in Asian and Caucasian women living in the UK and women living in Delhi, India, found menopause experiences and symptoms to be different in the three groups. All three groups experienced hot flushes, but these were described as more intense and severe by the UK Asian women compared with the UK Caucasian women, and many of the Delhi group did not report flushes at all. UK Caucasian women were more likely to report tiredness and low energy associated with night sweats, whereas both Asian groups talked about weight gain, visual disturbances, blood pressure and arthralgia[16].

The UK Caucasian women were more likely to report sexual problems and vaginal dryness and the Asian groups were more likely to report anxiety, panic and palpitations. For both the UK and Delhi Asian groups, ending menstruation also signified the beginning of ill health[16]. The study of women in Karachi somewhat mirrored this finding, with women reporting “thakan mehsoos hoti hai (I feel tired). Am not able to do all the household work now”[11]. This led to a loss of identity as the ‘woman of the house’ and feelings of unworthiness.

GP practices with a higher prevalence of patients with diabetes may prescribe less HRT, suggesting that a diagnosis of diabetes may influence other clinical decision making[17]. It may also result in South Asian women, in whom the risk of diabetes is more pronounced, having reduced access to HRT.

In a study that included four ethnic groups (African American, white, Japanese and Chinese), bone mineral density was found to be lowest in the Japanese and Chinese women, and highest in the African American women, who have a reduced risk of osteoporosis[18]. Healthcare can focus on chronic disease at the expense of menopause care, and access to such care may be further encumbered by cultural and communication barriers[19]. Women from ethnic minorities have been found to be less likely than white women to use HRT, and the uptake of other preventive health measures was lower in South Asian women than in white or African Caribbean women[20].

The most current research relevant to black UK women was published in 2007[21]. However, the total cohort was only 22 BAME women, 15 of whom identified as black, and the researchers did not report results by ethnicity[21]. The American SWAN study found that black women start menopause up to two years earlier and experience more severe symptoms for a longer duration, compared with white women[22]. This study concluded that BAME women cope differently with menopausal symptoms and may not want HRT as their first line of treatment[23]. This could be a financial decision, owing to how the American healthcare system is structured.

The benefits and risks of HRT

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance recommends HRT as first-line treatment for vasomotor symptoms and states that, for most women, the benefits of treatment outweigh the risks[24]. HRT is recommended for low mood associated with menopause[24]. This is the recommendation for all women and there is not currently any evidence that suggests women from different ethnic groups have different needs.

Continuous combined HRT (daily oestrogen and progestogen with no break) preparations are licensed for use in post-menopausal women and sequential HRT (daily oestrogen but progestogen only for part of the menstrual cycle) is normally used in peri-menopausal women. This is to support the gradual transition of the ovaries into being dormant; usual practice is that a woman can change to continuous combined HRT after one year of sequential use[24].

The earlier that HRT is started, the lower the future risk of cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis[25]. If HRT is started within ten years of menopause or before the age of 60 years, there is a reduced risk of atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease and overall mortality, with no increased risk of stroke or venous thromboembolism when using transdermal oestrogen[26,27]. There is also evidence showing benefit in reducing risk of diabetes, dementia, colorectal cancer and improvements in lipid profile[25].

More recent evidence, published after the latest review by NICE, explored a large-scale dataset of medical insurance records in the United States[28]. HRT use lowered women’s risk of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, which disproportionately affect women[28]. Newer, body-identical forms of HRT have greater efficacy in this respect (body-identical hormones have the same molecular structure as the hormones in the body)[28]. Research suggests that the protective effects are more pronounced when HRT is initiated when peri-menopausal symptoms begin[29].

Micronised progesterone is associated with a lower risk of venous thromboembolism, cardiovascular disease and breast cancer, compared with synthetic progestogens[30]. The French E3N study looked at breast cancer risk in relation to different types of HRT and showed no evidence of increased risk of breast cancer when micronised progesterone is used with transdermal oestradiol for up to five years[31]. Oral oestrogens with synthetic progestins showed a borderline increased risk of breast cancer with increased duration of use[31]. In women who have had a hysterectomy and are able to take unopposed oestradiol, breast cancer risk is in fact reduced[32].

Alternatives to HRT

The entire dialogue around menopause and HRT is changing worldwide, as awareness increases. However, women in different parts of the world are changing their preferences at different paces and, in many ethnic groups, alternatives to HRT remain a primary choice.

There are a range of methods women use to reduce the impact of symptoms. US studies suggest that around 30–80% of women who experience hot flushes try non-hormonal therapies[33]. Many women find these to be helpful, and the British Menopause Society advises taking lifestyle steps to support the menopause transition, although research evidence on some, such as exercise to reduce hot flushes, is limited[34].

Women from South Asia, whose diets tend be more plant-based, tend to suffer from fewer hot flushes, night sweats and skin changes from lack of oestrogen. However, they commonly have more body aches, palpitations and urinary symptoms from the change in oestrogen, progesterone and testosterone. This often leads to menopause and HRT being considered as a cause for these symptoms much later, and sometimes over-investigation or reluctance to treat.

A study involving women of Asian origin found that they saw menopause as a natural process, did not seek medical help and medicated with herbal remedies[35]. This may be owing to lack of knowledge of the risks and benefits of HRT and difficulty gaining access to female doctors of the same ethnic group. Yoga is widely practiced in many countries and there is evidence that it can have beneficial effects for women in menopause, although further robust evidence is awaited[36].

Although there may be some individual benefit to using alternatives to HRT, the placebo effect may be as great as 30–50%[37]. Most HRT alternatives only improve vasomotor symptoms (night sweats, hot flashes and flushes), rather than the collective symptoms, and none are as effective as oestrogen[38].

There is some evidence for a beneficial effect of isoflavones, black cohosh and St John’s wort on menopausal symptoms, but there have been reports of liver toxicity with black cohosh used for more than six months[38]. Because of oestrogenic activity, neither black cohosh nor isoflavones should be used by patients with breast cancer. St John’s wort is known for its many drug interactions (e.g. with tamoxifen, oral contraceptives and selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]) and is often not suitable for use in women experiencing the menopause[24]. The safety and purity of these alternatives should be questioned, because of the lack of rigorous testing and product variation.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), acupuncture and nerve block have also been used to treat vasomotor symptoms[39]. The British Menopause Society states that CBT developed specifically for menopausal symptoms can help women to manage hot flushes and night sweats (vasomotor symptoms), and it has been found to be effective in three clinical trials for women going through the menopause and for patients with breast cancer[40–43]. Improvements were maintained at six-month follow up, and there were additional benefits to quality of life. The CBT approach is theory-based and focuses on stress and wellbeing, hot flushes, night sweats and sleep problems, over four to six weeks; it is available in self-help book and small group formats[4,6]. The North American Menopause Society recommends CBT as an effective non-hormonal treatment option for hot flushes and night sweats[40].

Some non-hormonal options available on prescription include SSRIs (avoid paroxetine and fluoxetine with tamoxifen), venlafaxine, gabapentin, pregabalin and clonidine[33]. These can be useful options to consider for women in whom HRT is contraindicated and the clinician responsible for care is best placed to have a shared choice-based discussion around this[24].

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) is a comprehensive term that includes vulvovaginal symptoms and lower-urinary-tract symptoms related to low oestrogen levels (see Figure 1 and Box 1). This is a consistently identified predictor of impaired sexual health in women and studies have shown that around 70% of women have symptoms of GSM, yet only 7% receive treatment[44].

Vaginal dryness can be helped by simple lubricants, but the best and most logical treatment for urogenital atrophy is local oestrogen, such as 10mcg oestradiol pessary, estriol cream or an estriol vaginal ring. Local oestrogen is safe, effective and has few contraindications; treatment should be started early and before irrevocable atrophic changes occur[45,46].

The prevalence of vaginal dryness increases as women advance through their postmenopausal years, causing itching, burning and dyspareunia, and sexual activity is often compromised. Despite the various safe and effective treatment options, only a minority (about 25% of women in the Western world) seek medical help[45,46].

A paper addressing global variation in attitudes to vaginal atrophy identified common themes among women in Europe, Asia, India, Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East[46]. These ranged from a need for better information and education on the implications of vaginal atrophy on their quality of life and sexual function, to reluctance to seek help because of shyness or taboo[46]. Interestingly, 63% of women indicated that they did not seek treatment as they believed vaginal problems were natural after menopause[46]. Most women thought that improving vaginal health may improve their quality of life and would have liked to discuss the problem if their doctors had initiated the discussion[46].

“I tried to say I was uncomfortable down below, I told the doctor ‘I felt my lower body was numb and not mine’. They looked at me perplexed and said this was a consequence of ageing and I felt dismissed and ashamed.” (A patient with genitourinary syndrome of menopause from the authors’ own practice.)

Some of this reluctance might be owing to the adverse publicity for HRT in previous years that suggested an increased risk of breast cancer, heart disease and stroke[45]. However, local treatment of vaginal atrophy has never been associated with these possible risks of systemic HRT. Medical professionals should ask all postmenopausal women about vaginal atrophic symptoms, especially considering the impact these symptoms have and the reluctance to talk about them in some ethnic groups.

Drug metabolism differences and ethnicity

The limited available evidence suggests that there is much that we may not be aware of when considering HRT in different ethnicities. Most ethnic sensitivity to pharmacokinetics is thought to be owing to genetic polymorphisms of enzymes involved in metabolism[47]. However, the variation is not unique to particular ethnic groups and should be considered on an individual basis[47].

If oral therapy is being considered, diet and body weight can have a significant effect on drug absorption and distribution; additionally, there are interracial differences in the relationship between obesity, metabolic health and risk of cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women[12].

The absorption of transdermal preparations can differ according to ethnicity, age, disease, skin hydration and application site[48]. There is evidence of lower permeation across Afro-Caribbean skin, possibly because the stratum corneum is denser in structure and has lower subcutaneous water content compared with other ethnicities; therefore, higher doses would be required to reach the same plasma drug levels as in other ethnicities[48]. The order of absorption from lowest to highest was found to be Afro-Caribbean, Asian, Caucasian and Hispanic[48].

Asian women have significantly higher serum oestradiol levels during transdermal HRT compared with white women. This suggests a difference in metabolism and clearance[49]. Hill et al. found that plasma oestradiol levels in Japanese, Bantu and Caucasian women differ, and this may be partially owing to dietary factors[50]. There is little evidence for other ethnicities. This could influence prescribing once further guidance is established.

DNA methylation is recognised as a potential biomarker for underlying health disparities between ethnic groups[51]. Methylation is an important step in the metabolism of oestrogen and may be affected if the process does not have the required nutritional cofactors. Methylation is particularly reliant on folate and vitamin B12, which the British South Asian population are often deficient in[52]. The importance of eating folate-rich and vitamin-B12-rich foods and supplementation for vegetarians and vegans should therefore be reinforced with BAME women.

How can pharmacists help?

Pharmacists are in a unique position, not only as accessible healthcare professionals but also by virtue of their demographic characteristics. Of 56,264 pharmacists registered with the General Pharmaceutical Council in 2019, 37% were Asian or Asian British, 6% were black or black British and 36% were white British[53]. This is a marked contrast with 56.2% of senior doctors being of white ethnicity and 31.4% being Asian[54].

According to the 2011 census, people from a Bangladeshi ethnic background living in the UK are most likely to not speak English proficiently or at all[54]. Women of Pakistani or Bangladeshi background are five times more likely than men of the same background to speak no English at all[54].

Being able to communicate and raise awareness in individuals from some ethnic minority groups can be difficult. However, it is something that pharmacists already often have to do when dispensing medication, perhaps through an English-speaking relative, or a member of staff with skills in the same language as the patient. There are some excellent resources available that patients can be referred to; for example, there are relevant information videos available in Punjabi, Hindi and Spanish. As awareness and effectiveness increases, material in more languages may become available.

There are many ways that pharmacists can help BAME patients (see Box 2). One of the most important is to recognise the symptoms of menopause in all women and to consider peri-menopause in all unexplained symptoms/untreated illness.

Box 2: What can pharmacists do to help women in minority ethnic groups?

- Improve awareness and representation of ethnically diverse women in menopause conversations;

- Be aware of different health and cultural beliefs and, if unsure, ask the patient;

- Use translational services/media if required;

- Consider peri-menopause and menopause in frequently presenting patients with non-specific symptoms or polypharmacy;

- Educate about the importance of lifestyle changes. Use any discussion as an opportunity to advise patients on the importance of nutrition (non-processed, whole foods, plant-based foods that include soya), sleep, stress management, exercise, safe alcohol limit and positive social networks;

- Raise the long-term risks of menopause and the comparable benefits of HRT;

- Be aware of the need for medicines review in BAME women, especially considering differences in pharmacodynamics;

- Peri-menopause and menopause should be actively treated with lifestyle changes and/or HRT, as the health implications are significant;

- Liaise with other healthcare professionals at GP practices and, if appropriate, consider a serum oestradiol level check in ethnic women who are not stable on their current HRT regimen;

- Develop and pursue an interest in menopause management;

- Be aware that most alternatives to HRT do not have any proven evidence of efficacy.

Conclusion

There is a need for cohesive community approaches to menopause care for all women. The Fawcett study on ‘Menopause and the workplace’ demonstrates that reform in menopause care is urgently required. It found:

- One in ten women who worked during the menopause have left a job owing to their symptoms;

- Eight in ten women say their employer has not shared information, trained staff, or put in place a menopause absence policy;

- Almost half of women have not approached their GPs about the menopause and three in ten of those who have experienced delays in diagnosis;

- Only four in ten women who have talked to their GP about the menopause say they were immediately offered HRT[9].

This article has highlighted the barriers women from BAME groups can face accessing and responding to menopause care. Furthermore, there may be a reluctance to see a male doctor, IT challenges to accessing counselling material and financial constraints related to prescription charges. In addition, although the media is beginning to report more on the problems of menopause, its focus tends to be on the stories of white women.

For a clinician, it can be challenging to combine the management of chronic diseases, such as diabetes, with the treatment of non-specific symptoms of menopause, especially when faced with challenges of workload, cultural variations and health beliefs. However, the current momentum in menopause awareness and evidence points to the integration of menopause care being crucial, and we need further studies to investigate effective measures to help menopausal women. The principles of treatment remain the same regardless of ethnicity, but it is vital to be aware that attitudes and response to treatment may differ.

There is a lack of robust research around ethnic differences in women at menopause; however, available information shows physiological, biochemical, pharmacokinetic, sociological and psychological variation and differences in symptom reporting. With an ageing population, it is projected that by 2030, 1.2 billion women will be menopausal or postmenopausal[4]. If we are to take a preventive approach, then early education, lifestyle modification and promotion of safe HRT to all symptomatic women needs to be at the forefront.

Resources

Conflict of interest statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

- 1Sarri G, Davies M, Lumsden MA, et al. Diagnosis and management of menopause: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2015;351:h5746–h5746. doi:10.1136/bmj.h5746

- 2Maciejewska-Jeske M, Szeliga A, Męczekalski B. Consequences of premature ovarian insufficiency on women’s sexual health. pm. 2018;17:127–30. doi:10.5114/pm.2018.78557

- 3National life tables — life expectancy in the UK: 2017 to 2019. Office for National Statistics. 2020.https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/lifeexpectancies/bulletins/nationallifetablesunitedkingdom/2017to2019 (accessed Sep 2022).

- 4Sussman M, Trocio J, Best C, et al. Prevalence of menopausal symptoms among mid-life women: findings from electronic medical records. BMC Women’s Health. 2015;15. doi:10.1186/s12905-015-0217-y

- 5Maas AHEM, Rosano G, Cifkova R, et al. Cardiovascular health after menopause transition, pregnancy disorders, and other gynaecologic conditions: a consensus document from European cardiologists, gynaecologists, and endocrinologists. European Heart Journal. 2021;42:967–84. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa1044

- 6Thurston RC, Aslanidou Vlachos HE, Derby CA, et al. Menopausal Vasomotor Symptoms and Risk of Incident Cardiovascular Disease Events in SWAN. JAHA. 2021;10. doi:10.1161/jaha.120.017416

- 7Hillman S, Shantikumar S, Ridha A, et al. Socioeconomic status and HRT prescribing: a study of practice-level data in England. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70:e772–7. doi:10.3399/bjgp20x713045

- 8Measuring Poverty 2020. Social Metrics Commission. 2020.https://socialmetricscommission.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Measuring-Poverty-2020-Web.pdf (accessed Sep 2022).

- 9Menopause and the workplace. Fawcett Society. 2022.https://www.fawcettsociety.org.uk/menopauseandtheworkplace (accessed Sep 2022).

- 10Women’s health: migrant health guide. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. 2014.https://www.gov.uk/guidance/womens-health-migrant-health-guide (accessed Sep 2022).

- 11Asad N, Somani R, Peerwani N, et al. “I am not the person I used to be”: Perceptions and experiences of menopausal women living in Karachi, Pakistan. Post Reprod Health. 2021;27:199–207. doi:10.1177/20533691211060099

- 12Schmiegelow MD, Hedlin H, Mackey RH, et al. Race and Ethnicity, Obesity, Metabolic Health, and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Postmenopausal Women. JAHA. 2015;4. doi:10.1161/jaha.114.001695

- 13Nappi RE, Chedraui P, Lambrinoudaki I, et al. Menopause: a cardiometabolic transition. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2022;10:442–56. doi:10.1016/s2213-8587(22)00076-6

- 14Kodama K, Tojjar D, Yamada S, et al. Ethnic Differences in the Relationship Between Insulin Sensitivity and Insulin Response. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1789–96. doi:10.2337/dc12-1235

- 15Baird J, Yogeswaran G, Oni G, et al. What can be done to encourage women from Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds to attend breast screening? A qualitative synthesis of barriers and facilitators. Public Health. 2021;190:152–9. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2020.10.013

- 16Hunter MS, Gupta P, Papitsch-Clark A, et al. Mid-Aged Health in Women from the Indian Subcontinent (MAHWIS): a further quantitative and qualitative investigation of experience of menopause in UK Asian women, compared to UK Caucasian women and women living in Delhi. Climacteric. 2009;12:26–37. doi:10.1080/13697130802556304

- 17Cobin RH, Goodman NF. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Position Statement on Menopause–2017 Update. Endocrine Practice. 2017;23:869–81. doi:10.4158/ep171828.ps

- 18Finkelstein JS, Lee M-LT, Sowers M, et al. Ethnic Variation in Bone Density in Premenopausal and Early Perimenopausal Women: Effects of Anthropometric and Lifestyle Factors. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2002;87:3057–67. doi:10.1210/jcem.87.7.8654

- 19Raleigh V, Holmes J. The health of people from ethnic minority groups in England. The Health of People from Ethnic Minority Groups in England. 2021.https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/health-people-ethnic-minority-groups-england (accessed Sep 2022).

- 20Harris TJ, Cook DG, Wicks PD, et al. Ethnic differences in use of hormone replacement therapy: community based survey. BMJ. 1999;319:610–1. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7210.610

- 21Ozuzuzu-Nwaiwu J. Black women’s perceptions of menopause and the use of HRT. Nursing Times. 2007.https://www.nursingtimes.net/archive/black-womens-perceptions-of-menopause-and-the-use-of-hrt-09-03-2007/ (accessed Sep 2022).

- 22Gold EB. The Timing of the Age at Which Natural Menopause Occurs. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 2011;38:425–40. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2011.05.002

- 23Harlow SD, Burnett-Bowie S-AM, Greendale GA, et al. Disparities in Reproductive Aging and Midlife Health between Black and White women: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). womens midlife health. 2022;8. doi:10.1186/s40695-022-00073-y

- 24Menopause: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2015.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng23 (accessed Sep 2022).

- 25Scheyer O, Rahman A, Hristov H, et al. Female Sex and Alzheimer’s Risk: The Menopause Connection. J Prev Alz Dis. 2018;:1–6. doi:10.14283/jpad.2018.34

- 26Schierbeck LL, Rejnmark L, Tofteng CL, et al. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular events in recently postmenopausal women: randomised trial. BMJ. 2012;345:e6409–e6409. doi:10.1136/bmj.e6409

- 27Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, et al. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002229.pub4

- 28Kim YJ, Soto M, Branigan GL, et al. Association between menopausal hormone therapy and risk of neurodegenerative diseases: Implications for precision hormone therapy. A&D Transl Res & Clin Interv. 2021;7. doi:10.1002/trc2.12174

- 29Mosconi L, Brinton RD. How would we combat menopause as an Alzheimer’s risk factor? Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2018;18:689–91. doi:10.1080/14737175.2018.1510320

- 30Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ. 2019;:k4810. doi:10.1136/bmj.k4810

- 31Fournier A, Berrino F, Riboli E, et al. Breast cancer risk in relation to different types of hormone replacement therapy in the E3N-EPIC cohort. Int. J. Cancer. 2005;114:448–54. doi:10.1002/ijc.20710

- 32Women’s Health Initiative: the final outcome. British Menopause Society. 2006.https://thebms.org.uk/2006/04/womens-health-initiative-the-final-outcome/ (accessed Sep 2022).

- 33Biglia N, Bounos VE, De Seta F, et al. Non-hormonal strategies for managing menopausal symptoms in cancer survivors: an update. ecancer. 2019;13. doi:10.3332/ecancer.2019.909

- 34Daley A, Stokes-Lampard H, Thomas A, et al. Exercise for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006108.pub4

- 35Huang K-E, Xu L, I NN, et al. The Asian Menopause Survey: Knowledge, perceptions, hormone treatment and sexual function. Maturitas. 2010;65:276–83. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.11.015

- 36Cramer H, Peng W, Lauche R. Yoga for menopausal symptoms—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2018;109:13–25. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.12.005

- 37Woyka J. Consensus statement for non-hormonal-based treatments for menopausal symptoms. Post Reprod Health. 2017;23:71–5. doi:10.1177/2053369117711646

- 38Non-hormonal-based treatments for menopausal symptoms. British Menopause Society. 2022.https://thebms.org.uk/publications/consensus-statements/non-hormonal-based-treatments-menopausal-symptoms/ (accessed Sep 2022).

- 39Guo P-P, Li P, Zhang X-H, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine for natural and treatment-induced vasomotor symptoms: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2019;36:181–94. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2019.07.007

- 40Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) for Menopausal Symptoms. British Menopause Society. 2017.https://thebms.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/01-BMS-TfC-CBT-03-AUGUST2022.pdf (accessed Sep 2022).

- 41Ayers B, Smith M, Hellier J, et al. Effectiveness of group and self-help cognitive behavior therapy in reducing problematic menopausal hot flushes and night sweats (MENOS 2). Menopause. 2012;19:749–59. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e31823fe835

- 42Duijts SFA, van Beurden M, Oldenburg HSA, et al. Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Physical Exercise in Alleviating Treatment-Induced Menopausal Symptoms in Patients With Breast Cancer: Results of a Randomized, Controlled, Multicenter Trial. JCO. 2012;30:4124–33. doi:10.1200/jco.2012.41.8525

- 43Mann E, Smith MJ, Hellier J, et al. Cognitive behavioural treatment for women who have menopausal symptoms after breast cancer treatment (MENOS 1): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2012;13:309–18. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70364-3

- 44Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Vaginal Health: Insights, Views & Attitudes (VIVA) – results from an international survey. Climacteric. 2011;15:36–44. doi:10.3109/13697137.2011.647840

- 45Newson L, Kirby M, Stillwell S, et al. Position Statement for Management of Genitourinary Syndrome of the Menopause (GSM) . British Society for Sexual Medicine. 2020.http://www.bssm.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/GSM-BSSM.pdf (accessed Sep 2022).

- 46Sturdee DW, Panay N. Recommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2010;13:509–22. doi:10.3109/13697137.2010.522875

- 47Olafuyi O, Parekh N, Wright J, et al. Inter‐ethnic differences in pharmacokinetics—is there more that unites than divides? Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2021;9. doi:10.1002/prp2.890

- 48Singh I, Morris A. Performance of transdermal therapeutic systems: Effects of biological factors. Int J Pharma Investig. 2011;1:4. doi:10.4103/2230-973x.76721

- 49Huddleston HG, Rosen MP, Gibson M, et al. Ethnic variation in estradiol metabolism in reproductive age Asian and white women treated with transdermal estradiol. Fertility and Sterility. 2011;96:797–9. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.06.023

- 50Hill P, Wynder E, Helman P, et al. Plasma hormone levels in different ethnic populations of women. Cancer Res 1976;36:2297–301.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/132269

- 51Kader F, Ghai M. DNA methylation-based variation between human populations. Mol Genet Genomics. 2016;292:5–35. doi:10.1007/s00438-016-1264-2

- 52O’Logbon J, Crook M, Steed D, et al. Ethnicity influences total serum vitamin B12 concentration: a study of Black, Asian and White patients in a primary care setting. J Clin Pathol. 2021;75:598–604. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2021-207519

- 53Survey of registered pharmacy professionals 2019. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2019.https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/document/gphc-2019-survey-pharmacy-professionals-equality-diversity-inclusion-report-december-2019.pdf (accessed Sep 2022).

- 54Ethnicity facts and figures. UK Government. 2022.www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk (accessed Sep 2022).