Evgeniy Salov / Alamy Stock Photo

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the causes of premature ovarian insufficiency (POI);

- List the required diagnostic tests and the serious health consequences linked with POI diagnosis;

- Provide information on the benefits and risks of hormonal treatment options;

- Advise on emerging non-hormonal treatment options available for symptom relief.

Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI; also known as premature ovarian failure) is where the ovaries stop functioning before the age of 40 years and affects around 1% of women in the UK[1]. It can be a devastating diagnosis for women of reproductive age and differs from early menopause, which occurs in women aged between 40 and 45 years.

Data suggest a genetic aetiology and increased incidence in women of African-American, Hispanic and white ethnicity. Use of female hormones, cigarette smoking, osteoporosis and severe disability are associated with increased risk of POI in white women[2]. In African-American women, POI is associated with higher body mass index and use of female hormones[3].

Women with a diagnosis of POI should be treated by a multidisciplinary team, with a management plan that includes pharmacological therapy and appropriate counselling and support. Pharmacists are essential in reviewing the patient’s medical profile holistically — this includes the hormonal therapy essential for POI management and in minimising the risks of other medical conditions that may arise as a consequence of POI, such as osteoporosis and depression.

Symptoms

Cessation of ovarian function causes low oestrogen levels (hypo-oestrogenaemia), which commonly manifests as an irregular menstrual cycle; however, women can experience a range of physical, psychological and sexual symptoms (see Box 1).

Box 1: Symptoms of premature ovarian insufficiency

Physical

- Hot flushes;

- Night sweats;

- Heat intolerance;

- Palpitations (awareness of heartbeat);

- Infertility;

- Changes to skin and hair (e.g. dryness, thinning);

- Headaches;

- Breast tenderness;

- Fat redistribution;

- Needing to pass urine more often and with more urgency;

- Pain passing urine;

- Urinary tract infection/cystitis.

Psychological

- Mood changes and irritability;

- Lethargy;

- Difficulty concentrating;

- Anxiety/panic attacks;

- Depression;

- Sleep disturbance/insomnia;

- Fatigue;

- Lowered self-esteem.

Sexual

- Reduced sex drive;

- Vaginal dryness;

- Pain during sexual intercourse (dyspareunia).

The severity and frequency of symptoms varies from person to person. Affected women report reduced health-related quality of life owing to infertility leading to pregnancy failures, increased incidence in cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis owing to low bone mineral density[2].

Risk factors and causes

POI cannot be predicted or prevented, but around 37.5% of affected women report a family history[4]. Other risk factors include history of exposure to cytotoxic agents and radiation, autoimmune disease (most commonly Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) and chromosomal alterations (see Box 2[5]).

Box 2: Causes of premature ovarian insufficiency

Primary

- Chromosomal disease (e.g. Turner’s syndrome);

- Follicle-stimulating hormone-receptor gene polymorphism;

- Mutation of inhibin B;

- Auto-immune disorders (e.g. autoimmune oophoritis);

- Enzymatic defects.

Secondary

- Cancer treatment (e.g. chemotherapy, radiotherapy);

- Ovarian surgery;

- Uterine artery embolism;

- Infections (e.g. tuberculosis, mumps).

Diagnosis

Most POI cases are idiopathic — that is, the cause is not known. However, many endocrine disorders can cause menstrual disorders, so it is always necessary to check levels of thyroid stimulating hormones (TSH) and prolactin.

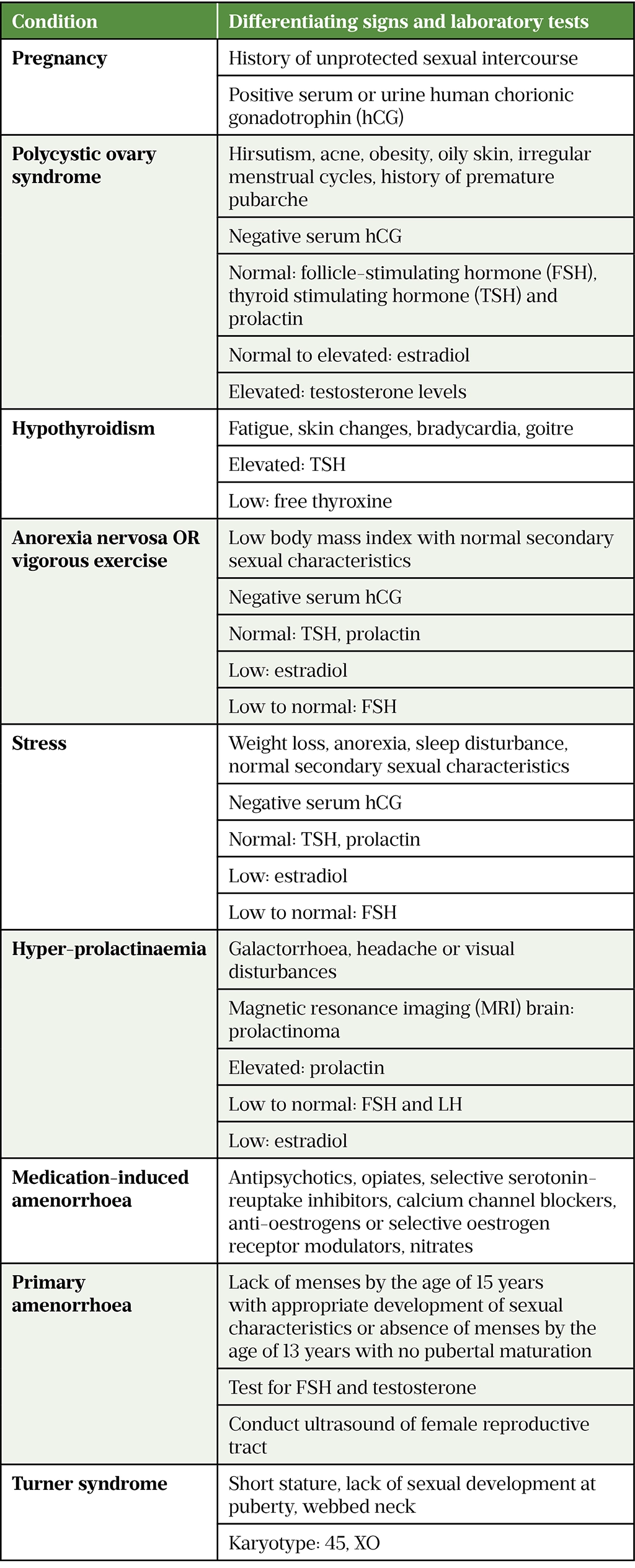

Many other conditions have symptoms that present in women with POI and must be ruled out before a diagnosis of POI can be confirmed (see Table 1[1]).

A diagnosis of POI is made based on clinical symptoms and hormone blood tests. POI is likely in a woman who is not on contraception, presenting with menopausal symptoms and elevated serum follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) levels (>30 IU/L) on two consecutive blood samples taken four to six weeks apart[1]. Routine pelvic examination is not required for diagnosis and it should only be performed to exclude other possible causes of menopausal symptoms[6].

After confirmed diagnosis, all patients require chromosomal analysis to assess the risk of gonadal neoplasia and should undergo testing for possible autoimmune disease, such as endocrine disorders (mainly adrenal insufficiency, Hashimoto thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes mellitus) and non-endocrine disorders (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis)[2].

Management

Management of POI should follow a holistic approach and include psychological support, fertility treatment options and replenishment of oestrogen hormone levels with hormone replacement therapy (HRT), unless contraindicated.

Hormone replacement therapy

Oestrogen and oestrogen receptors are not limited to the female reproductive tract. Oestrogen affects the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems, brain, skin, hair, urinary tract and mucous membranes. Therefore, oestrogen deficiency inevitably results in an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, depression, urinary incontinence and many other symptoms typically seen post menopause[7]. In fact, the use of HRT before the age of 60 years has been shown to reduce the risk of coronary heart disease by 24% and total mortality by 30%[8]. Oestrogen replenishment through HRT remains the mainstay of treatment for POI.

Multiple HRT regimens are available but the regimen and formulation should be monitored and adjusted to best manage symptoms with the lowest risk of side effects (see further discussion below).

Treatment should be initiated at a low dose, titrated according to response and can be continued up to the average age of natural menopause and potentially to the licensed recommended age specified in the summary of product characteristics (SPC) of the formulation — most commonly 65 years. The average age for natural menopause in the UK is 51 years[6].

There are four common combinations of HRT:

- Continuous combined regimen of oestrogen and progesterone daily;

- Cyclical combined regimen of oestrogen and progesterone for days 1–25 of each month, followed by withdrawal bleeding on days 26–31;

- Cyclical oestrogen for days 1–21 of each month with progesterone for days 7–21 and withdrawal bleeding on days 22–30;

- Cyclical daily oestrogen with progesterone added for 14 days of the month and withdrawal bleeding in the middle of the month[6].

The continuous combined regimen avoids menstrual blood flow and is usually the easiest to follow; however, it is only recommended after one year of amenorrhea. In the meantime, a cyclical regimen with monthly menstrual cycle is recommended[6].

HRT is available in oral, topical, vaginal, transdermal and subcutaneous formulations with detailed prescribing information on the different formulations outlined in section 8 of the British National Formulary[6,9]. The formulation should be chosen based on patient preference and risk factors. In general, better health outcomes are seen with the transdermal oestrogen and vaginal progesterone combination, compared with systemic oral oestrogen and progesterone formulations[10]. Transdermal oestrogen preparations have been associated with reduced systemic increase of blood pressure compared to oral formulations[10].

To minimise the risk of endometrial cancer, it is vital that all women with an intact uterus receive a HRT formulation that includes progesterone[6]. However, low-strength vaginal oestrogen HRT formulations (e.g. estradiol 10 micrograms pessary and estriol 0.01% cream used for dyspareunia and/or atrophic vaginitis) do not require the addition of opposed progesterone because they do not raise systemic oestrogen levels above the normal post-menopausal range[6,11,12].

The starting oral oestrogen dose for women with POI is usually 2mg/day (100 micrograms/day for transdermal formulations), with the dose titrated according to response and symptom control and follow the information and guidance outlined in the SPC[13].

Vaginal oestrogen can be used as an adjunct to alleviate vaginal dryness, atrophy and/or urinary symptoms associated with oestrogen deficiency[13]. Low-strength topical oestrogen vaginal formulations (e.g. estriol 0.01% cream) and pessaries are available and can be used in conjunction with other HRT therapy. However, the European Medicines Agency issued a warning regarding the use of high strength vaginal formulations containing >0.01% (100 micrograms/gram) of estradiol. These must not be combined with systemic or transdermal HRT therapy because of the increased risk of side effects — mainly blood clots and breast cancer[14]. It should be noted that such high-strength vaginal oestrogen formulations are not used in the UK and this concern must not be extrapolated to the use of low-dose vaginal oestrogen formulations, as discussed previously[14].

Many women and clinicians remain anxious about the perceived increased risk of breast cancer linked with HRT therapy. The risk of breast cancer in females with POI is not as widely investigated as that in females who began HRT after the age of natural menopause. In fact, some studies reported that HRT does not affect breast density or increase the risk of breast cancer in females with POI taking HRT[15–18]. Patients should be reassured that HRT up to the age of natural menopause is merely replacing the oestrogen that the body would otherwise have produced.

Contraindications to HRT

Prior to advising or initiation of any HRT regimen, pharmacists should screen patients for any potential contraindication to the prescribing of HRT. In cases where it is contraindicated, GP referral should be made for further discussion and specialist advice (e.g. gynaecology) may be required for advice on other non-hormonal options (see below).

The contraindications to HRT are:

- Unexplained vaginal bleeding;

- History of stroke or transient ischaemic attack; myocardial infarction; pulmonary embolism or venous thromboembolism; unless the patient is already on anticoagulation;

- Current, past, or suspected breast or endometrial cancer;

- Active liver disease; known protein C, protein S, or antithrombin deficiency or other thrombophilic disorders;

- Known or suspected pregnancy[19].

Side effects to HRT

The most common side effect of HRT is unscheduled vaginal bleeding within the first three months of the regimen and is different to the regular, scheduled bleeding that occurs at the end of the progesterone phase in cyclical regimens[6]. Continuous combined HRT can also result in irregular breakthrough bleeding or spotting in the first four to six months of treatment. Endometrial pathology needs to be excluded if bleeding persists beyond six months or reoccurs after a period of reported amenorrhea.

In the case where the woman reports such a bleeding pattern, the pharmacist must refer them to their GP for further investigation. After excluding any endometrial pathology, the progesterone component of the formulation can be adjusted[6,9]. The prescriber will either increase the dose, extend the duration of the progesterone in the cyclical regimen, or offer a different type of progesterone (e.g. intrauterine levonorgestrel-releasing system with oral or transdermal oestrogen formulation).

Other reported side effects are typically related to one of the two main hormones used: oestrogen and progesterone. Oestrogen-related adverse effects include fluid retention, bloating, nausea, headaches, dyspepsia, leg cramps and breast tenderness or enlargement. Further testing based on the suspected diagnosis (e.g. BNP for heart failure, Helicobacter pylori antigen for dyspepsia, full blood count for suspected headaches associated with anaemia) may be required to help rule out other pathological causes.

In cases where diagnostic tests are positive and pathological causes have not been ruled out, further investigation and specialist referral, such as to a cardiologist, may be warranted. Otherwise, where pathological causes have been ruled out and based on the competency level of the pharmacist and/or GP, an alternative formulation of HRT with a lower dose of oestrogen can be offered[9].

Progesterone-related adverse effects include fluid retention, breast tenderness, headaches/migraines, change in mood, depression, acne vulgaris, abdominal pain and back pain. A different formulation with a lower dose of progesterone can be offered after other pathological causes have been ruled out[9].

Testosterone supplementation

As well as oestrogen, the ovaries also produce testosterone. In POI, testosterone production is significantly reduced, or sometimes completely diminished[20,21]. As a result, women may experience reduced sexual desire. In the UK, the use of testosterone for reduced libido remains an off-label indication and initiation requires specialist knowledge[9]. Evidence on effectiveness is still limited. It is usually initiated in women already on HRT but with persistent symptoms of reduced libido that affect their quality of life or relationship with their partner. The only formulation designed for women currently available is a cream, AndroFeme 1 (Lawley Pharma)[22]. This is not yet available on NHS prescription and needs to be prescribed privately[23].

Supportive measures

The psychological effects of a POI diagnosis can significantly affect quality of life and many women can feel anxious and distressed. Diagnosis needs to be discussed in a very sensitive and timely manner and professional counselling can help reduce the associated anxiety. Pharmacists can signpost patients to support groups, such as the Daisy Network Premature Menopause Support Group, which can help patients form a supportive network with others with a similar diagnosis.

Family planning should also be discussed. Although the chance of pregnancy in women with POI is significantly reduced, 5–10% of women experience spontaneous resolution and may become pregnant[24]. Therefore, women should be counselled that HRT does not have any contraceptive effects. Those not planning for pregnancy must use an additional barrier method (condom) and/or contraceptive pills. However, progesterone-only pills need to be offered if required and HRT should not be given together with the combined oral contraceptive pill[6]. HRT should be stopped immediately if a patient becomes pregnant.

Women hoping to conceive in the future can opt for oocyte donation, which requires specialist care. Oocyte donation treatment is complicated and beyond the scope of this article. GPs, community and practice-based pharmacists and other healthcare professionals can signpost patients to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority for information on the different options available.

Bone care

Oestrogen plays an essential role in the regulation of osteoclasts and generation of osteoblasts, and a deficiency inevitably results in a significant reduction in the patient’s bone mass[25–27]. HRT in women with POI should mimic the normal ovarian function and provide hormonal balance like that of healthy women.

Nevertheless, lifestyle interventions such as smoking cessation, muscle-strengthening exercise, controlled alcohol intake and calcium and vitamin D supplementation are still necessary to slow decline in bone mineral density (BMD). According to World Health Organization guidelines, a daily intake of vitamin D 800 IU and calcium 1000mg is sufficient to maintain BMD without increasing the risk of kidney stones and cardiovascular disease[28]. BMD assessment should be performed by a dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan.

In women with a confirmed diagnosis of osteoporosis, bisphosphonates remain a first-line treatment. Bisphosphonates reduce risk of vertebral fractures by 50–60% and non-vertebral fractures by 20–30%[29]. Different bisphosphonates are available with different dosing regimens and choice should be made according to patient preference if possible. All bisphosphonates are contraindicated in pregnancy and they should not be used in women planning to conceive[30].

Non-hormonal treatments

HRT is the most effective treatment option for POI. In cases where the patient chooses not to take HRT or if it is contraindicated, the following non-hormonal treatments are available and may provide some symptom relief.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors — such as fluoxetine 20mg daily, citalopram 20mg daily, paroxetine 10mg daily or venlafaxine 75mg daily — can be trialled off-label for two weeks to manage vasomotor symptoms — mainly hot flashes and night sweats[6]. Clonidine is also licensed in the UK for management of hot flushes and vasomotor symptoms of menopause at a dose of 50 micrograms twice daily for two weeks, and can be increased if necessary to 75 micrograms twice daily. Gabapentin (unlicensed indication) can also be given at a low dose initially: 300mg once daily and increased gradually over three days to a maximum of 300mg three times daily, if tolerated[6].

Patients experiencing low mood and/or any associated anxiety or signs of depression may consider self-referral or be referred by their GP for free NHS talking therapies, including cognitive behavioural therapy. For more information, patients and family members can be directed to the NHS Talking Therapies web page.

Over-the-counter vaginal moisturisers can be used twice weekly to aid with vaginal dryness and daily lubricants can be used to minimise dyspareunia.

Best practice recommendations on how pharmacists and pharmacy teams should support women to manage POI are outlined in Box 3.

Box 3: Best practice recommendations

Pharmacists should:

- Be able to differentiate between women experiencing natural menopause and those presenting with signs and symptoms of premature ovarian insufficiency. Referral to a GP should be made promptly to confirm diagnosis of premature ovarian insufficiency (POI);

- Be sensitive when advising women about the serious health consequences associated with a new diagnosis of POI. Advice on bone care, management of increased cardiovascular risks and low mood/anxiety needs to be discussed fully and patients should be signposted to appropriate services where possible;

- Provide lifestyle advice to women with POI and present the evidence base and rationale for bone-protection treatment to minimise risk of cardiovascular events, psychological distress and osteoporosis;

- Counsel women on the safe use of HRT for POI, unless contraindicated. The different options and formulations of HRT should be discussed privately in a consultation room;

- Where HRT is contraindicated or declined by the patient, provide information on non-hormonal treatment options and lubricants available to manage vasomotor symptoms, low mood and anxiety.

- 1Premature Ovarian Insufficiency: Information for patients. The Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust. 2019.http://flipbooks.leedsth.nhs.uk/LN003682P/LN003682.pdf (accessed May 2022).

- 2Rudnicka E, Kruszewska J, Klicka K, et al. Premature ovarian insufficiency – aetiopathology, epidemiology, and diagnostic evaluation. pm. 2018;17:105–8. doi:10.5114/pm.2018.78550

- 3Luborsky JL, Meyer P, Sowers MF, et al. Premature menopause in a multi-ethnic population study of the menopause transition. Human Reproduction. 2003;18:199–206. doi:10.1093/humrep/deg005

- 4Cramer DW, Xu H, Harlow BL. Family history as a predictor of early menopause*. Fertility and Sterility. 1995;64:740–5. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57849-2

- 5Atabiekov I, Hobeika E, Sheikh U, et al. The Role of Gene Therapy in Premature Ovarian Insufficiency Management. Biomedicines. 2018;6:102. doi:10.3390/biomedicines6040102

- 6Scenario: Managing women with menopause, perimenopause, or premature ovarian insufficiency. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2022.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/menopause/management/management-of-menopause-perimenopause-or-premature-ovarian-insufficiency (accessed May 2022).

- 7Oliver MF, Boyd GS. EFFECT OF BILATERAL OVARIECTOMY ON CORONARY-ARTERY DISEASE AND SERUM-LIPID LEVELS. The Lancet. 1959;274:690–4. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(59)92129-4

- 8Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, et al. Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease by Age and Years Since Menopause. JAMA. 2007;297. doi:10.1001/jama.297.13.1465

- 9British National Formulary. British National Formulary. https://bnf.nice.org.uk (accessed May 2022).

- 10Langrish JP, Mills NL, Bath LE, et al. Cardiovascular Effects of Physiological and Standard Sex Steroid Replacement Regimens in Premature Ovarian Failure. Hypertension. 2009;53:805–11. doi:10.1161/hypertensionaha.108.126516

- 11Estradiol 10 mcg Vaginal Tablets. Electronic Medicines Compendium. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11779/smpc#gref (accessed May 2022).

- 12Estriol Cream. Electronic Medicines Compendium. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/12876/smpc#gref (accessed May 2022).

- 13Torrealday S, Kodaman P, Pal L. Premature Ovarian Insufficiency – an update on recent advances in understanding and management [version 1; peer review: 3 approved]. F1000 Research. 2017.https://f1000research.com/articles/6-2069 (accessed May 2022).

- 14Four-week limit for use of high-strength estradiol creams . European Medicines Agency . 2019.https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/four-week-limit-use-high-strength-estradiol-creams (accessed May 2022).

- 15Webber L, Anderson RA, Davies M, et al. HRT for women with premature ovarian insufficiency: a comprehensive review. Human Reproduction Open. 2017;2017. doi:10.1093/hropen/hox007

- 16Benetti-Pinto CL, Soares PM, Magna LA, et al. Breast density in women with premature ovarian failure using hormone therapy. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2008;24:40–3. doi:10.1080/09637480701690543

- 17Ewertz M, Mellemkjaer L, Poulsen AH, et al. Hormone use for menopausal symptoms and risk of breast cancer. A Danish cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1293–7. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602472

- 18Bösze P, Tóth A, Török M. Hormone Replacement and the Risk of Breast Cancer in Turner’s Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2599–600. doi:10.1056/nejmc062795

- 19Shifren JL, Schiff I. Role of Hormone Therapy in the Management of Menopause. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2010;115:839–55. doi:10.1097/aog.0b013e3181d41191

- 20Premature ovarian failure. BMJ Best Practice. 2020.https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/1004 (accessed May 2022).

- 21Soman M, Huang L-C, Cai W-H, et al. Serum androgen profiles in women with premature ovarian insufficiency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause. 2019;26:78–93. doi:10.1097/gme.0000000000001161

- 22ANDROFEME 1 testosterone 1% w/v (10 mg/mL) cream tube. Australian Department of Health (Therapeutic Goods Administration). 2021.https://myhealthbox.eu/en/androfeme-1-testosterone-1-w-v-10-mg-ml-cream-tube/5602603 (accessed May 2022).

- 23Testosterone replacement in menopause. British Menopause Society. https://thebms.org.uk/publications/tools-for-clinicians/testosterone-replacement-in-menopause/#:~:text=AndroFeme%20is%20not%20currently%20available,special%20license%20from%20the%20MHRA (accessed May 2022).

- 24van Kasteren Y. Premature ovarian failure: a systematic review on therapeutic interventions to restore ovarian function and achieve pregnancy. Human Reproduction Update. 1999;5:483–92. doi:10.1093/humupd/5.5.483

- 25Popat VB, Calis KA, Kalantaridou SN, et al. Bone Mineral Density in Young Women With Primary Ovarian Insufficiency: Results of a Three-Year Randomized Controlled Trial of Physiological Transdermal Estradiol and Testosterone Replacement. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2014;99:3418–26. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-4145

- 26Anasti J. Bone Loss in Young Women With Karyotypically Normal Spontaneous Premature Ovarian Failure. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1998;91:12–5. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00583-8

- 27Uygur D, Sengül Ö, Bayar D, et al. Bone loss in young women with premature ovarian failure. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;273:17–9. doi:10.1007/s00404-005-0029-7

- 28Osteoporosis – prevention of fragility fractures: Scenario: Management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/osteoporosis-prevention-of-fragility-fractures/management/management/ (accessed May 2022).

- 29ESHRE Guideline: management of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Reprod. 2016;31:926–37. doi:10.1093/humrep/dew027

- 30Osteoporosis – prevention of fragility fractures: Bisphosphonates. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/osteoporosis-prevention-of-fragility-fractures/prescribing-information/bisphosphonates (accessed May 2022).