Shutterstock.com

Around 3,200 women in the UK are diagnosed with cervical cancer each year, with the disease occurring most frequently in younger women (aged under 45 years)[1]

. Cervical cancer can also develop in transgender men who have not had a hysterectomy[2]

.

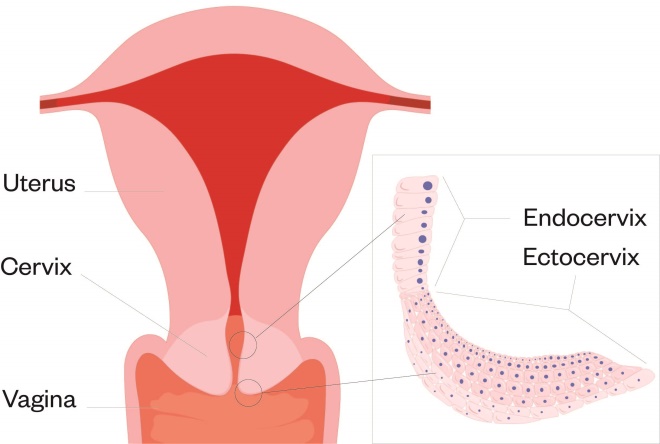

The cervix is located at the neck of the womb and is connected to the vagina. It is made up of different cells: on the outer surface, at the top of the vagina, the layer is called the ectocervix and is made up of skin-like cells, whereas glandular cells, which produce mucus, cover the lining of the inside of the cervix and are called the endocervix (see Figure)[3]

. Changes to the ectocervix and glandular cells in this area over time can lead to cancer of the cervix, or cervical cancer, which normally develops slowly (e.g. over several years)[4]

.

There are two main types of cervical cancer. The most common is squamous cell carcinoma (originating in the ectocervix), which accounts for around 70-80% of diagnoses[4],[5]

. The other type is adenocarcinoma, arising from cells in the endocervix; however, these are less common and account for around 20% of diagnoses[4],[5]

. Other, much rarer, types of cervical cancer include adenosquamous carcinoma, small cell and clear cell cancer[4],[5]

.

Cervical cancer, like other cancers, is graded depending on how abnormal the cells look under a microscope, and staged according to how big the tumour is and whether or not it has spread[3],[5]

. Spread can occur through the lymphatic system, which normally filters and drains tissue fluid and helps protect against infections in the body[3],[5]

. Generally, lymph nodes play an important part in cancer spread as cancer cells that ‘break away’ from the primary site may spread to the lymph nodes[3],[5]

. It is typical that, during surgery for cervical cancer, surrounding lymph nodes will be removed and later checked in the laboratory for cancer cells[3],[5]

.

Figure: Diagram of the cervix

Source: McLean/Shutterstock.com

This article outlines how to recognise the signs and symptoms of cervical cancer, its causes and risk factors, and the role of pharmacists and their teams in promoting screening to encourage and improve uptake.

Signs and symptoms

Often, cancer of the cervix does not cause symptoms in its early stages; therefore, screening is vital for its early identification[6],[7]

.

However, when symptoms do present, vaginal bleeding is often one of the first symptoms to be noticed[6]

. Although this bleeding is normal for many women, there is a particular cause for concern when this bleeding occurs:

Other symptoms may include pain during sex, an unpleasant vaginal discharge, pain in the pelvic area and recurrent urinary tract infections[6],[7]

. These symptoms are fairly broad and can be a sign of other conditions (e.g. pelvic inflammatory disorder or endometrial atrophy); therefore, it would be appropriate to refer the patient to their GP for further investigation. When referring patients, it is necessary to be firm that there is a need for further investigation, but balance this by trying not to exacerbate fears (e.g. refrain from using terms such as ‘worrying symptoms’)[8]

.

If the cancer has spread beyond the cervix and into surrounding lymph nodes or tissue, other symptoms could include:

- Constipation;

- The need to urinate or pass a bowel movement more frequently;

- Urinary and bowel incontinence;

- Haematuria;

- Swelling of one or both legs[6]

.

It is particularly important for pharmacists and their teams to identify women who present regularly with similar requests (e.g. repeat prescriptions for medicines for urinary tract infections or repeated requests for laxatives). If there are concerns, the pharmacist should discuss these with the patient.

Causes and risk factors

There are a variety of causes and risk factors for cervical cancer, some of which are general and can be applicable to other cancers (see below). Pharmacy teams need to be aware of these to be able to confidently educate their patients. This could be through raising public awareness of cancers and their causes, and ensuring that they themselves are up to date with educational resources that can support them.

Age

Similar to many other cancers, age is a risk factor, with cervical cancer more common in younger women. The highest incidence rate is in women aged 30–34 years[9]

. This then drops until age 50–54 years and then falls again beyond 80 years[9]

.

Smoking

Cigarette smoking not only increases the risk of developing cervical cancer, but also makes it harder to treat as smoking is associated with a higher symptom burden and can have an impact on the effect of radiotherapy

[10]

. The risk is increased by the duration that the individual has smoked and how many cigarettes are smoked each day[10]

. For every 15 cigarettes that are smoked, there is a DNA change that could cause a cancerous cell to develop[10]

. Pharmacy teams should take all opportunities to encourage smoking cessation through services or via over-the-counter management.

Contraceptive pill

Cervical cancer has been linked with the combined contraceptive pill, and there is a higher risk with a longer duration (more than 5 years) of use[9]

. The risk has been shown to increase by 60% with 5–9 years of use and double with 10 or more years of use[11]

. However, the risk does reduce as soon as the medication is stopped[9]

. The combined contraceptive pill increases the risk of breast cancer by 24%, but can reduce the risk of both womb (30%) and ovarian cancers (30–50%) [12],[13],[14]

. Although patients are likely to have received counselling when first prescribed their medicine, it is important that pharmacists ensure they counsel the patient on appropriate use and take the opportunity to remind patients of the associated risks, including cervical cancer.

Humanpapilloma viruses

The human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are the cause of 99.7% of cervical cancer cases in the UK[15]

. There are over 200 types of HPV, with the majority causing warts and verrucae; however, there are around 12 types that are considered high-risk for cervical cancer[15]

. The high-risk types 16 and 18 cause 70% of all cervical cancers[16]

.

HPV affects the skin and mucous membranes (e.g. the inside of the mouth, throat, genital areas or anus)[17]

. The immune system has the ability to clear the virus, but if this does not happen (e.g. if the individual has a weakened immune system) and the infection remains in the body for long periods of time, the risk of cervical cancer is increased[17]

.

The virus is spread, in men and women, during intercourse or other types of sexual activity (e.g. oral sex)

[17]. The risk may be higher for individuals who began to have sex at a younger age (owing to earlier introduction of HPV); have had lots of sexual partners (owing to higher HPV exposure); or have HIV — women with HIV are more likely to have persistent HPV infection[18],[19],[20]

. Condoms and other barrier contraceptive methods can reduce the risk of infection, but will not completely prevent transmission as these methods can fail[9]

.

Other risk factors

Additional factors that can increase the risk of cervical cancer include women giving birth before the age of 17 years, having a family history of cervical cancer (it is not known whether this is through genetics or shared lifestyle) and having current cancer of the vagina, vulva, kidney or urethra[9]

.

Prevention

Cervical screening

An important factor that increases the likelihood of a positive outcome in cervical cancer is ensuring that cervical screening takes place in order to identify the disease early[4],[21]

. It is essential that pharmacy teams take any opportunity to reinforce this message because, according to the charity Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust, almost a quarter of a million women aged 25–29 years did not attend their smear test in England in 2016[22]

. Data from the charity shows that 26.7% women feel too embarrassed to attend[22]

.

In the UK, the NHS provides cervical screening to women aged between 25 and 64 years[23]

. Women aged between 25 years and 49 years will be invited to attend screening every 3 years, whereas women aged between 50 years and 64 years will be invited every 5 years[24]

. For the latter group, the reduced frequency is owing to the low risk of women at this age developing cervical cancer, particularly if they have had several previous negative test results[25]

. Screening is not offered to women below the age of 25 years as changes to cells of the cervix are very common and cervical cancer is rare below this age[26]

. Between 2015 and 2017, there were only 75 cases of cervical cancer in women below the age of 25 years[1]

.

The purpose of screening is to detect the presence of HPV and abnormal cell changes that could develop into cervical cancer[27]

. The invitation is sent through the GP, meaning that women who are not currently registered with a GP should be informed that they need to organise their own screening tests. This can be done by registering with a GP, visiting a walk-in centre that offers cervical screening or going to a sexual health service. Transgender men, who are registered as a male at their GP, may not automatically be sent a letter; therefore, if they have a cervix, they may need to contact their GP to arrange a test[28]

.

Some individuals may feel nervous and uncomfortable about screening, so specialist clinics are available for people who may not want to go to their GP for screening. For example, CliniQ is a transgender clinic that offers cervical screening and My Body Back Project offers services to women who have experienced sexual assault[29],[30],[31]

.

Screening appointments

A smear test is usually performed by a female nurse and takes a matter of minutes. It is normally conducted with the woman lying on her back, but if this is uncomfortable for them then they can lie on their side[29],[32]

. The test is performed when a woman is not menstruating. A speculum (a medical tool for investigating body orifices) is inserted into the vagina, so that the nurse can clearly see the cervix[29],[32]

. The nurse will use a soft brush to take a sample of cells from the cervix; these are then put into a sample pot and sent to the laboratory[29],[32]

. The method of cell collection and preparation is known as liquid-based cytology[23]

. This method ensures that all cells collected are retained for slide preparation for viewing under the microscope[27]

. Results are normally reported two to six weeks after the screening test[33]

. Women will normally receive a letter in the post, but may also receive the results through text messaging or email. It is important to be conscious of the fact that many women are apprehensive about cervical screening — the experience can be uncomfortable, particularly if the individual is tense. If a patient is apprehensive, you should refer them to patient-orientated information about the process, such as Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust.

HPV testing

In England, Wales and Scotland, the cells taken from the cervix are tested for HPV (known as HPV primary screening)[29]

. In Northern Ireland, the cells are examined under a microscope for abnormalities first. If any changes are detected, the cells will then be tested for HPV. However, Northern Ireland will be changing to HPV primary screening in line with England, Wales and Scotland[29]

. Testing for HPV first, rather than looking for abnormalities, has been shown to be a more sensitive test[27]

.

If HPV is not found, then the individual will continue receiving invitations for screening, according to the age bracket they fall under. If high-risk HPV is detected, then the same sample will be used to carry out a cytology triage (i.e. looking at a small cluster of cells in order to determine an anomaly)[27]

. If there are no cell changes then the individual will be invited back for screening in one year. If changes are detected, the individual will be invited for a colposcopy (a more detailed examination of the cervix) and further tests[34]

.

Other prevention strategies

Vaccination

Girls aged 12–13 years should receive the HPV vaccination. It has been offered to girls who are in year 8 of school since 2010 in England[35]

. From September 2019, it has also been offered to boys in year 8 of school in England[35]

.

It is important that the vaccine is administered before the onset of sexual activity and exposure to HPV[36]

. Individuals can get the vaccine up to the age of 25 years, without charge, from the NHS if they missed the opportunity at school[35]

. This can be conducted through their GP.

There are three types of vaccine — Cervarix (GlaxoSmithKline UK), Gardasil and Gardasil 9 (Merck Sharp & Dohme Limited):

- Cervarix protects against HPV types 16 and 18 — these are estimated to be responsible for 70% of cervical cancers;

- Gardasil protects against HPV types 6, 11, 16 and 18. HPV 6 and 11 are responsible for 90% of genital warts and 10% of low-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia;

- Gardasil 9 protects against HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, as well as 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58, and is anticipated to protect against 90% of cervical cancers[37],[38],[39]

.

The dosing for each of the different types of vaccines varies slightly, but all require a course of two or more doses (see Table)[37],[38],[39]

.

| Vaccine | Route | Age (years) | Dose (dosing intervals) |

|---|---|---|---|

Cervarix | Intramuscular | 9–14 | 0.5ml (0, 5–13 months) |

≥15 | 0.5ml (0, 1, 6 months) | ||

Gardasil | Intramuscular | 9–13 | 0.5ml (0, 6 months) or 0.5ml (0, 2, 6 months) |

≥14 | 0.5ml (0, 2, 6 months) | ||

Gardasil 9 | Intramuscular | 9–14 | 0.5ml (0, 6-12 months) or 0.5ml (0, 2, 6 months) |

≥15 | 0.5ml (0, 2, 6 months) | ||

Safe sex

Practising safe sex can help to prevent spread of HPV[9]

. Barrier methods, such as condoms, can reduce the risk of developing the infection, but the virus can be transmitted through other sexual activities, such as skin-to-skin contact between genitals, oral sex and the use of sex toys[9]

. The risk of contracting HPV has been shown to be reduced in those who have fewer sexual partners[19]

.

Best practice

There are opportunities for pharmacists working in hospital, community and general practice to educate and provide advice to individuals about cervical cancer. For example, pharmacy teams should:

- Work with young people aged 9 years and over, highlight the risks of cervical cancer, as well as introducing them to the HPV vaccination programme;

- Remind individuals about their screening appointments, explaining their importance to patients and dispelling any myths about the purpose of the test;

- Identify any warning signs or symptoms that could indicate cervical cancer and highlight these to medical teams when appropriate, or encourage the individual to make an urgent appointment with their GP;

- Display leaflets and posters within their pharmacies, surgery or outpatient area;

- Provide training sessions within their networks and to other healthcare professionals on the importance of cervical screening, recognising symptoms and understanding how to discuss these topics with patients;

- Be a source of ongoing support for patients in their care who have cervical cancer.

About the authors

Melanie Dalby is Macmillan patient experience and engagement lead for cancer and pharmacist at Barts Health NHS Trust; Yvonne Law is oncology pharmacist specialising in gynaecology and uro-oncology at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust.

How to have effective consultations on contraception in pharmacy

What benefits do long-acting reversible contraceptives offer compared with other available methods?

Community pharmacists can use this summary of the available devices to address misconceptions & provide effective counselling.

Content supported by Bayer

References

[1] Cancer Research UK. Cervical cancer statistics. 2020. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/cervical-cancer (accessed September 2020)

[2] NHS. Should trans men have cervical screening tests? 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/common-health-questions/sexual-health/should-trans-men-have-cervical-screening-tests/ (accessed September 2020)

[3] Cancer Research UK. What is cervical cancer? 2020. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cervical-cancer/about (accessed September 2020)

[4] Macmillan Cancer Support. What is cervical cancer? 2020. Available at: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/cervical-cancer#1_what_is_cervical_cancer (accessed September 2020)

[5] Cancer Research UK. Cervical cancer stages, types and grades. 2020. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cervical-cancer/stages-types-grades/types-and-grades (accessed September 2020)

[6] NHS. Cervical cancer symptoms. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cervical-cancer/symptoms/ (accessed September 2020)

[7] The Eve Appeal. What is cervical cancer? 2014. Available at: https://eveappeal.org.uk/gynaecological-cancers/cervical-cancer/ (accessed September 2020)

[8] Lewis J. Identifying patients with suspected cancer: red flags and referral. Pharm J 2018:301(7918). doi: 10.1211/PJ.2018.20205538

[9] Cancer Research UK. Cervical cancer risks and causes. 2020. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cervical-cancer/risks-causes (accessed September 2020)

[10] Cancer Research UK. How does smoking cause cancer? 2018. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/causes-of-cancer/smoking-and-cancer/how-does-smoking-cause-cancer (accessed September 2020)

[11] Smith JS, Green J, Berrington de Gonzalez A et al. Cervical cancer and use of hormonal contraceptives: a systematic review. Lancet 2003;361(9364):1159–1167. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12949-2

[12] Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53,297 women with breast cancer and 100,239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet 1996;347(9017):1713–1727. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90806-5

[13] Michels KA, Pfeiffer RM, Brinton LA & Trabert B. Modification of the associations between duration of oral contraceptive use and ovarian, endometrial, breast, and colorectal cancers. JAMA Oncology 2018;4(4):516–521. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4942

[14] Wentzensen N, Poole EM, Trabert B et al. Ovarian cancer risk factors by histologic subtype: An analysis from the Ovarian Cancer Cohort Consortium. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(24):2888–2898. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.8178

[15] Burd EM. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev 2003;16(1):1–17. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.1-17.2003

[16] Clifford GM, Smith JS, Aguado T & Franceschi S. Comparison of HPV type distribution in high-grade cervical lesions and cervical cancer: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2003;89(1):101–105. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601024

[17] Macmillan Cancer Support. Human papilloma virus. 2018. Available at: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/worried-about-cancer/causes-and-risk-factors/hpv (accessed September 2020)

[18] Plummer M, Peto J & Franceschi S. Time since first sexual intercourse and the risk of cervical cancer. Int J Cancer 2011;130(11):2638–2644. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26250

[19] Zhi-Chang L, Wei-Dong L, Yan-Hui L et al. Multiple sexual partners as a potential independent risk factor for cervical cancer: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015;16(9):3893–3900. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.9.3893

[20] Ghebre RG, Grover S, Xu MJ et al. Cervical cancer control in HIV-infected women: past, present and future. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2017:21:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2017.07.009

[21] Macmillan Cancer Support. Cervical screening. 2009. Available at: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/diagnostic-tests/cervical-screening (accessed September 2020)

[22] Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust. Barriers to cervical screening among 25-29 year olds. 2017. Available at: https://www.jostrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/ccpw17_survey_summary.pdf (accessed September 2020)

[23] National Institute for Heath and Care Excellence. Cervical screening: what is the purpose of the NHS cervical screening programme? 2017. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/cervical-screening/background-information/cervical-screening-programme/ (accessed September 2020)

[24] NHS. Cervical cancer prevention. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cervical-cancer/prevention/ (accessed September 2020)

[25] Blanks RG, Moss SM, Addou S et al. Risk of cervical abnormality after age 50 in women with previously negative smears. Br J Cancer 2009;100(11):1832–1836. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605069

[26] Mackie A. What is the right age for cervical screening? 2014. Available at: https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2014/04/28/what-is-the-right-age-for-cervical-screening/ (accessed September 2020)

[27] Government UK. Cervical screening: programme overview. 2019. Available at: www.gov.uk/guidance/cervical-screening-programme-overview#screening-tests (accessed September 2020)

[28] Macmillan Cancer Support. Cervical screening. 2020. Available at: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/diagnostic-tests/cervical-screening#3_who (accessed September 2020)

[29] Cancer Research UK. About cervical screening. 2020. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cervical-cancer/getting-diagnosed/screening/about (accessed September 2020)

[30] CliniQ. Sexual health and clinical services. 2015. Available at: https://cliniq.org.uk/www-cliniq-org-uk/sexual-health-clinical-services (accessed September 2020)

[31] My Body Back Project. Our St Bartholomew’s cervical screening clinic opens on 6th August. 2015. Available at: http://www.mybodybackproject.com/?s=cervical&submit=Search (accessed September 2020)

[32] NHS. What happens at your cervical screening appointment? 2020. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cervical-screening/what-happens-at-your-appointment/ (accessed September 2020)

[33] NHS Digital. Cervical screening statistics, England 2018–2019. 2019. Available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/cervical-screening-annual/england—2018-19 (accessed September 2020)

[34] NHS. Colposcopy. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/colposcopy/ (accessed September 2020)

[35] NHS. HPV vaccine overview. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/hpv-human-papillomavirus-vaccine/ (accessed September 2020)

[36] World Health Organization. Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, May 2017 — recommendations. Vaccine 2017;35(43):5753–5755. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.05.069

[37] Electronic medicines compendium. Cervarix. 2020. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/20204#gref (accessed September 2020)

[38] Electronic medicines compendium. Gardasil suspension for injection. 2019. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/261/smpc#gref (accessed September 2020)

[39] Electronic medicines compendium. Gardasil 9. 2020. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/32240#gref (accessed September 2020)