Sciencephoto.com

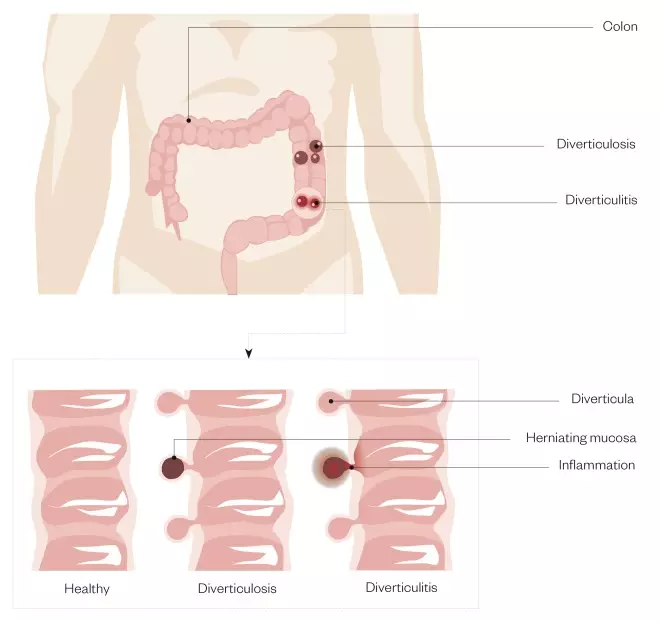

Diverticulosis is a digestive condition that mainly affects the sigmoid colon. Diverticulosis develops when a section of the mucosa pushes out or herniates through a weak area of muscle in the wall of the colon. The exact mechanism causing this is not known, but is thought to be related to raised intra-colonic pressure in segmented portions of the colon as a result of the contraction of the muscular wall[1],[2]

. This bulge forms a sac, known as a diverticulum (plural diverticulae). The disease at this stage is termed ‘diverticulosis’ — the presence of diverticulae without symptoms. Once symptoms develop, the term ‘diverticular disease’ is used, and the inflammation that gives rise to symptoms is known as ‘diverticulitis’ (see Figure).

Figure 1: Diverticulosis and diverticulitis

Diverticulosis occurs when pouches (diverticula) develop in the wall of the colon. Diverticulitis is when these pouches become inflamed or infected.

Diverticular disease is a chronic condition, with symptoms remitting and relapsing[3]

; it is common in older people living in developed countries. With ageing populations and advances in recognition and diagnosis, Painter and Burkitt highlighted in 1971 that “diverticular disease was almost unknown in 1900, but has become the most common affliction of the colon in Western countries within 70 years — the traditional life span of man”.[4]

Around 5–10% of people aged 45 years and over have diverticulosis, and this figure rises to 80% in people aged 85 years and over[5]

. Hospital admissions in England for diverticular disease were found to have more than doubled from 0.56 per 1,000 population to to 1.2 per 1,000 population over the ten years from 1996 to 2006[6]

. In 2017, of the 532,130 deaths registered in England and Wales, 1,511 were from diverticular disease[7]

.

This article will describe the risk factors, symptoms and treatment of this condition, and the role pharmacists can play in supporting patients.

Risk factors

Smoking, a history of constipation, and long-term regular use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and aspirin are associated with diverticular disease[8]

. Age is the largest risk factor in any population, although others include gender, genetics, diet and lifestyle.

Age

In the under 50 years age group, men are more likely than women to develop diverticular disease. Between the ages of 50 years and 70 years, women are slightly more likely to develop the condition, and the risk increases for women compared to men in the over 70 years age group[1]

.

Diet

Deficiency of dietary fibre was initially proposed as a major risk factor for diverticular disease by Painter and Burkitt[2]

. However, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s clinical knowledge summary highlights that “the recommendation on increasing dietary fibre is based on limited and conflicting evidence on the benefits for symptom relief and prevention of recurrent episodes of acute diverticulitis”[5]

. A 2018 meta-analysis of ten studies found a significant association between diverticulosis and obesity[9]

.

Genes

While diverticular disease generally affects the sigmoid colon in Western populations, right-sided colonic disease is more common in Asian populations[10]

. The genetic element in the pathogenesis of diverticular disease has also been substantiated in sibling and twin studies[11]

. In addition, people with Marfan syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, Williams–Beuren syndrome, Coffin–Lowry syndrome, and polycystic kidney disease are at increased risk of diverticulosis, which is more likely to develop at a younger age[12]

. In 2018, a genome study identified 42 loci, of which 39 were novel, associated with diverticular disease[13]

.

Symptoms

Often, people will be unaware that they have diverticulosis as they are not displaying any symptoms.

However, if one or more of the sacs become inflamed and infected (i.e. diverticulitis), acute symptoms can include severe lower abdominal pain and tenderness, fever and general malaise. Some diverticulae may bleed, so patients may notice blood in their stools. Symptoms are particularly severe in acute complicated diverticulitis, which affects around 5% of those with diverticulosis.

Diagnosis

Patients who are symptomatic may present in community pharmacy prior to consulting their GP. As symptoms are similar to those experienced in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), pharmacists should establish whether a diagnosis of diverticular disease has been made. The inflammatory component of diverticular disease, and the often more localised abdominal pain, provide clear differentials between IBS and diverticular disease[11]

.

Apart from other gastrointestinal conditions, differential diagnoses include gynaecological or urological conditions[4]

.

Questions to ask the patient:

- Have you experienced any unplanned weight loss?

- Have you experienced any abdominal symptoms?

- The patient may complain about eating less food and/or find that avoiding certain foods or food groups helps them manage their symptoms.

If either of these are the case, encourage the patient to discuss this with their GP to see if a referral to a dietitian is appropriate (see Box 1). Since smoking is thought to increase the patient’s risk[8]

, this can also present an opportunity to discuss smoking cessation and signpost patients to relevant smoking cessation services.

Box 1: Staging of acute diverticulitis and formal diagnosis of diverticulitis

Acute diverticulitis is diagnosed using the five-stage Hinchey’s classification, with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis comprising stages 0 and Ia, and acute complicated diverticulitis comprising stages Ib to IV[11]

:

- Stage 0: clinically mild diverticulitis;

- Stage Ia: pericolic inflammation;

- Stage Ib: pericolic or mesocolic <5cm abscess;

- Stage II: intra-abdominal, pelvic or retroperitoneal abscess, or abscess distant from the primary inflammation;

- Stage III: generalised purulent peritonitis;

- Stage IV: faecal peritonitis.

Referral

Encourage GP consultation if the patient has not yet received a diagnosis. Depending on the symptoms, bloods tests may be undertaken to look for inflammation, which include:

- Systemic

- C-reactive protein;

- White cell count.

- Intestinal

- Faecal calprotecin.

Other investigations include an ultrasound, CT scan and/or a colonoscopy.

Management

Diverticulosis

For asymptomatic diverticulosis, patients should be advised to eat a healthy, balanced diet. This includes achieving an intake of 30g/day of dietary fibre. When UK government guidelines on dietary carbohydrates were published in 2015, the average intake of fibre in adults among the general population was just 24g/day[5]

,[14]

. Therefore, it is important to explain to patients how they can increase their intake (e.g. by eating nuts, beans, cereals, and fresh and dried fruits). It is important to highlight that the benefits of increasing dietary fibre may take several weeks[5]

.

Diverticular disease

There has been a wide-held belief that people with diverticular disease should avoid nuts and seeds owing to the risk of small food particles becoming lodged in diverticulae, promoting or exacerbating local inflammation and infection. However, a large prospective study found no association between frequent consumption of nuts, corn and popcorn and the increased risk of diverticulosis or diverticular complications. Instead, the research suggested that higher consumption of these foods could protect against diverticulitis[15]

. Therefore, if the patient has symptoms, but does not require hospitalisation, they should also be advised to achieve an intake of 30g/day of dietary fibre[5]

.

If dietary fibre is insufficient, consider bulk-forming laxatives. Dietary fibre is the non-digestible part of plant cell walls. Soluble fibre dissolves in water to form a viscous gel, but insoluble fibre does not. Ispaghula husk (also known as psyllium) and sterculia are bulk-forming laxatives containing soluble fibre that increase retention of fluid in the stool, therefore softening it. A softer, bulkier stool puts less pressure on the wall of the colon and helps the passage through the colon by peristalsis. Besides fluid retention, fermentation of some soluble fibres (although not ispaghula husk) by gut bacteria can increase stool mass through increased mass of bacteria and stool lipid[16],[17]

.

Other bulk-forming laxatives include methylcellulose and wheat/oat bran, although the former is better tolerated with less risk of bloating and wind as it provides non-fermentable soluble fibre. Wheat bran contains a high proportion of insoluble fibre, which physically bulks stool mass. Insoluble fibre also irritates the colonic mucosa, increasing the secretion of mucus and water, therefore producing a laxative effect[16]

. Oat bran provides more of a mix of insoluble and soluble fibre[17]

.

Patients should be referred to a dietitian for advice on dietary modification of fibre intake. An increase in intake of soluble fibre can be advised, alongside laxatives. For instance, this could include: one tablespoon per day of ground linseeds sprinkled on foods or added to sauces; increasing the intake of oat-based foods, such as porridge or unsweetened oat biscuits; and/or eating fruits and vegetables (excluding, if necessary, the high-insoluble-fibre skins, seeds and stalks).

Adequate fluid intake (roughly 25–30mL/kg bodyweight) is recommended for everyone to reduce risk of constipation[18]

and is a major factor in the efficacy of laxatives, as well as to reduce the risk of associated intestinal obstruction[19]

.

Paracetamol should be recommended to alleviate abdominal pain. NSAIDs and opioids should be avoided as they increase the risk of complications (e.g. perforation)[12]

. In 2008, Piekarek et al. investigated whether NSAIDs, corticosteroids and opioids were significantly associated with an increased risk of complications of diverticular disease[20]

. They concluded that long-term use of opioids, which increase intra-colonic pressure and slow colonic transit, seems to increase the risk of diverticular perforation. Acetylsalicylic acid in cardiologic dose did not correlate with diverticular complications. Furthermore, corticosteroids were independently associated with perforated diverticular disease.

Acute diverticulitis

In acute diverticulitis, antibiotics are recommended only if there is suspected infection, which include co-amoxiclav, ciprofloxacin, metronidazole and rifaximin, depending on local guidelines. Watchful waiting is recommended in symptomatic diverticulosis where infection is not suspected.

The role of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis has been challenged. A multicentre randomised trial by Chabok et al. demonstrated that antibiotic treatment for acute uncomplicated diverticulitis neither accelerates recovery nor prevents complications or recurrence and, therefore, should be reserved for the treatment of complicated diverticulitis[21]

.

In colonic diverticulosis, luminal content stasis can lead to bacterial overgrowth[22]

. Rifaximin, a non-absorbable antibiotic, was investigated for diverticular disease. In a meta-analysis, Bianchi et al. concluded that in symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease, treatment with rifaximin plus fibre supplementation is effective in obtaining symptom relief and preventing complications[23]

. At one-year follow up, 64.0% of patients treated with rifaximin plus standard fibre supplement were symptom-free, compared with 34.9% of patients treated with fibre alone. The number needed to treat (NNT) was three for rifaximin versus placebo to achieve symptom relief. The NNT was nine to avoid complications of diverticular disease.

For acute diverticular disease requiring hospitalisation, intravenous fluids and antibiotics are a cornerstone of treatment. Emergency surgery may be required if a diverticulum perforates and for other serious complications (e.g. abscess, peritonitis, formation of a fistula or bowel obstruction)[5]

. This may include large bowel resection (known as a colectomy) with or without formation of a colostomy. A clear fluids diet is often recommended initially, progressing to a low-insoluble-fibre diet while symptoms resolve. A return to a standard fibre (30g/day) diet can be encouraged as soon as symptoms have resolved and/or after recovery from any surgery.

Current evidence base

There is research being performed regarding treatment options; however, there are currently insufficient data for them to be adopted in guidelines.

Antimuscarinics and calcium channel blockers

Hypermotility and higher pressure in the sigmoid colon have been observed in patients with diverticular disease compared with controls[24],[25]

. Therefore, altered motility in the colon is thought to contribute to symptoms of chronic diverticular disease; however, a definite correlation is yet to be established.

A UK case study showed a protective association between calcium channel blockers and perforated colonic diverticular disease. This association appears to be solely attributable to the modified release preparations of these drugs. No protective effect against perforation was found for antimuscarinic drugs[26]

. Piekarek et al. found that use of calcium channel blockers, which decrease intra-colonic pressure, was associated with a reduction in diverticular perforation. They also did not find any protective association between antimuscarinics and perforated colonic diverticular disease[23]

. However, further studies are required to confirm this association and the routine use of calcium channel blockers as preventive therapy in diverticular disease.

Chronic symptoms of diverticular disease, such as abdominal pain, bloating and altered bowel habit, can overlap with IBS, making diagnosis difficult. Antispasmodic agents can help with abdominal pain owing to IBS, and patients should be referred to a dietitian for advice.

Mesalazine

The anti-inflammatory drug mesalazine appears to act locally on colonic mucosa. The current hypothesis is that 5-aminosalicylic acid activates the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-gamma transrepressing several important target genes involved in inflammatory processes. PPAR-gamma is highly expressed in colonic inflammation and is involved in cell proliferation, apoptosis and modulation of cytokine production and anti-tumourigenic effects.

Mesalazine also acts as an inhibitor of mediators of lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase, interleukin-1, interleukin-2 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα). It has been recognised as a potent antioxidant and free-radical scavenger.

Tursi hypothesised in 2014 about the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of diverticular disease, ranging from increased inflammatory infiltrate to enhanced expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα[27]

. As such, diverticular disease may be considered as a chronic inflammatory process and, therefore, mesalazine may be potential therapeutic tool. A 2018 meta-analysis by Picchio et al. concluded that mesalazine is more effective than placebo in obtaining symptom relief and in preventing diverticulitis occurrence in symptomatic, uncomplicated diverticular disease[28]

.

Mesalazine has also been studied in combination with the use of rifaximin. Tursi et al. demonstrated that at one-year follow up, the combination therapy group (rifaximin 400mg twice per day and mesalazine 800mg twice per day for 7 days/month) did better than the monotherapy group with rifaximin alone in terms of symptom management, normalising bowel habits and preventing recurrence[29]

.

In a prospective, randomised open trial, Di Mario et al. compared the efficacy of cyclic use of rifaximin to mesalazine in achieving symptom relief in patients with symptomatic uncomplicated colonic diverticular disease. They found mesalazine was as effective as rifaximin for diminishing symptoms but better than rifaximin for improving the global score in those patients[30]

.

The gut microbiome

The colon is home to a diverse array of bacteria. The gut microbiome is, naturally, a target of research in diverticular disease, with probiotics potentially providing a relatively simple and cost-effective means of prevention and treatment[31]

. While differences in the gut microbiome have been identified in people with and without diverticular disease, translation into recommendations for use of probiotics is not yet possible[32],[33]

and further research is required.

Summary

Pharmacists and their teams should be aware of the signs and symptoms of diverticular disease and diverticulitis, and how they can support patients to manage their condtion by maintaining a healthy diet and advising on simple analgesia, where appropriate.

Useful additional resources

References

[1] World Gastroenterology Organisation. Diverticular disease. 2007. Available at: http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/guidelines/global-guidelines/diverticular-disease/diverticular-disease-english (accessed May 2019)

[2] Vermeulen J, van der Harst E & Lange JF. Pathophysiology and prevention of diverticulitis and perforation. Neth J Med 2010;68(10):303–309. PMID: 21071775

[3] Elisei W & Tursi A. The pathophysiology of colonic diverticulosis: inflammation versus constipation? Inflamm Intest Dis 2018;3(2):55–60. doi: 10.1159/000489173

[4] Painter NS & Burkitt DP. Diverticular disease of the colon: a deficiency disease of Western civilization. Br Med J 1971;2(5759):450–454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5759.450

[5] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical knowledge summaries: diverticular disease. 2019. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/diverticular-disease (accessed month 2018)

[6] Jeyarajah S, Faiz O, Bottle A et al. Diverticular disease hospital admissions are increasing, with poor outcomes in the elderly and emergency admissions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30(11–12):1171–1182. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04098.x

[7] Office for National Statistics. Mortality statistics for England and Wales 2017. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsregistrationsummarytables/2017 (accessed May 2019)

[8] NHS. Diverticular disease and diverticulitis. 2017. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/diverticular-disease-and-diverticulitis/ (accessed May 2019)

[9] Wijarnpreecha K, Ahuja W, Chesdachai S et al. Obesity and the risk of colonic diverticulosis: a meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 2018;61(4):476–483. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000999

[10] Imaeda H & Hibi T. The burden of diverticular disease and its complications: west versus east. Inflamm Intest Dis 2018;3(2):61–68. doi: 10.1159/000492178

[11] Lanas A, Abad-Boroja D & Lanas-Gimeno A. Progress and challenges in the management of diverticular disease: which treatment? Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2018;11:1756284818789055. doi: 10.1177/1756284818789055

[12] Böhm SK. Risk factors for diverticulosis, diverticulitis, diverticular perforation, and bleeding: a plea for more subtle history taking. Viszeralmedizin 2015;31(2):84–94. doi: 10.1159/000381867

[13] Maguire LH, Handelman SK, Du X et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 39 new susceptibility loci for diverticular disease. Nat Genet 2018;50(10):1359–1365. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0203-z

[14] Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. Press pelease: expert nutritionists recommend halving sugar in diet. 2015. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/446188/SACN_Carbohydrates_Press_Release_July_2015.pdf (accessed May 2019)

[15] Strate LL, Liu YL, Syngal S et al. Nut, corn, and popcorn consumption and the incidence of diverticular disease. JAMA 2008;300(8):907–914. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.907

[16] McRorie JW Jr & McKeown NM. Understanding the physics of functional fibers in the gastrointestinal tract: an evidence-based approach to resolving enduring misconceptions about insoluble and soluble fiber. J Acad Nutr Diet 2017;117(2):251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.09.021

[17] Chen HL, Haack VS, Janecky CW et al. Mechanisms by which wheat bran and oat bran increase stool weight in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;68(3):711–719. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.3.711

[18] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Algorithms for IV fluid therapy in adults. 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg174/resources/intravenous-fluid-therapy-in-adults-in-hospital-algorithm-poster-set-191627821 (accessed May 2019)

[19] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Constipation. 2017. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/constipation.html (accessed May 2019)

[20] Piekarek K & Israelsson LA. Perforated colonic diverticular disease: the importance of NSAIDs, opioids, corticosteroids, and calcium channel blockers. Int J Colorectal Dis 2008;23(12):1193–1197. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0555-4

[21] Chabok A, PÃ¥hlman L, Hjern F et al. Randomized clinical trial of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg 2012;99(4):532–539. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8688

[22] Ventrucci M, Ferrieri A, Bergami R & Roda E. Evaluation of the effect of rifaximin in colon diverticular disease by means of lactulose hydrogen breath test. Curr Med Res Opin 1994;13(4):202–206. doi: 10.1185/03007999409110484

[23] Bianchi M, Festa V, Moretti A et al. Meta-analysis: long-term therapy with rifaximin in the management of uncomplicated diverticular disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;33(8):902–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04606.x

[24] Bassotti G, Sietchiping-Nzepa F, De Roberto G et al. Colonic regular contractile frequency patterns in irritable bowel syndrome: the ‘spastic colon’ revisited. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;16(6):613–617. PMID: 15167165

[25] Huizinga J, Waterfall W & Stern H. Abnormal response to cholinergic stimulation in the circular muscle layer of the human colon in diverticular disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999;34(7):683–688. doi: 10.1080/003655299750025886

[26] Morris CR, Harvey IM, Stebbings WSL et al. Do calcium channel blockers and antimuscarinics protect against perforated colonic diverticular disease? A case-control study. Gut 2003;52(12):1734–1737. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.12.1734

[27] Tursi A. New physiopathological and therapeutic approaches to diverticular disease: an update. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2014;15(7):1005–1017. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.903922

[28] Picchio M, Elisei W & Tursi A. Mesalazine to treat symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease and to prevent acute diverticulitis occurrence. A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2018;27(3):291–297. doi: 10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.273.pic

[29] Tursi A, Brandimarte G & Daffinà R. Long-term treatment with mesalazine and rifaximin versus rifaximin alone for patients with recurrent attacks of acute diverticulitis of colon. Dig Liver Dis 2002;34(7):510–515. PMID: 12236485

[30] Di Mario F, Aragona G, Leandro G et al. Efficacy of mesalazine in the treatment of symptomatic diverticular disease. Dig Dis Sci 2005;50(3):581–586. PMID: 15810646

[31] Kvasnovsky CL, Bjarnason I, Donaldson AN et al. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of a multi-strain probiotic in treatment of symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease. Inflammopharmacology 2017;25(5);499–509. doi: 10.1007/s10787-017-0363-y

[32] Ojetti V, Petruzziello C, Cardone S et al. The use of probiotics in different phases of diverticular disease. Rev Recent Clin Trials 2018;13(2):89–96. doi: 10.2174/1574887113666180402143140

[33] Lanas A, Abad-Baroja D & Lanas-Gimeno A. Progress and challenges in the management of diverticular disease: which treatment? Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2018;11:1756284818789055. doi: 1756284818789055