JL / Shutterstock.com

Sore throat is a symptom resulting from an acute self-limiting upper respiratory tract infection (RTI), and is characterised by a dry scratchy throat and pain on swallowing[1],[2]

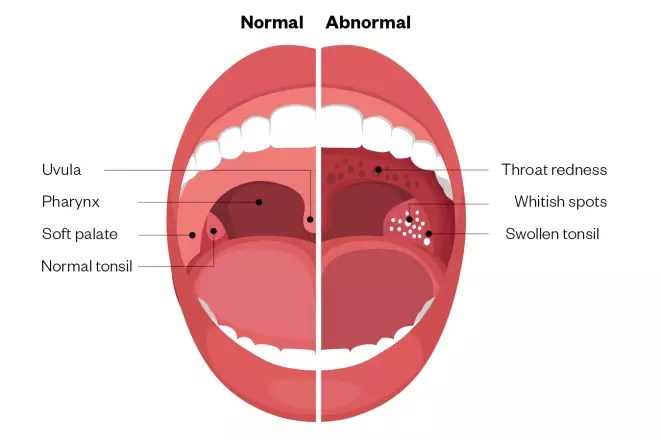

. The inflammation tends to be present in the back region of the throat (pharynx) and can encompass the back third of the tongue, roof of the mouth (the soft palate) and the tonsils (see Figure)[3]

. Conditions that commonly cause sore throats are laryngitis, tonsillitis and glandular fever.

Figure: Characteristics of a normal throat compared with an infected sore throat

Source: https://theydiffer.com/difference-between-strep-throat-and-tonsillitis

Although most sore throats are self-limiting and are caused by viral infections (and therefore do not require antibiotics), they are a common reason for GP consultations. One survey study showed that in Scotland in 2013, 31% of adults reported a severe sore throat in the previous year and 38% of these patients visited a GP[4]

.

Sore throat most commonly occurs in individuals aged 5–24 years; the highest incidence being in the early spring or winter months[4]

.

For patients presenting in community pharmacy with a sore throat, it is important to provide advice about how to manage symptoms through self-care, the normal symptom duration and the relevant public health messaging around appropriate prescribing of antimicrobials. Patients should also be informed about when to seek further medical advice.

Causes

Around 90% of sore throats that present in the pharmacy are caused by a viral infection (typically rhinovirus, influenza virus [types A and B], adenovirus, herpes simplex virus and Epstein–Barr virus[4]

) and can occur as part of the common cold[5]

. Although around 10% of sore throats are caused by a bacterial infection, most commonly group A Streptococcus

[6]

, it is clinically problematic to differentiate between the two causes as they both present with other overlapping symptoms, such as fever, enlarged lymph glands and pus-like exudate on the throat membrane (see Symptoms and differentials)[2]

.

Although less common, a sore throat can also have a non-infectious cause, including:

- Smoking;

- Side effects from drugs (e.g. antihistamines, antidepressants and diuretics);

- Various irritants (e.g. air pollution, chemicals);

- Traumatic injury (e.g. from a nasogastric tube);

- Hay fever;

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease[2],[4]

.

Symptoms and differentials

Symptoms of an infective cause of a sore throat may include:

- Throat pain, especially when swallowing;

- Dry, scratchy throat;

- Swollen neck glands;

- Redness at the back of the throat;

- Swollen tonsils;

- Whitish spots in the throat.

In younger children, symptoms such as fever, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain may also be present[4]

.

Symptoms can continue for seven to ten days, but most individuals will recover within a week without antibiotics, irrespective of the sore throat being caused by a viral or bacterial infection[1]

.

Patients may also present with other symptoms, which can be used to differentiate an acute self-limiting upper RTI from a more serious condition (see Box 1).

Box: Identifying red flags

Patients who present with the following red flag symptoms should be referred to their GP:

- Sore throat that lasts for longer than three weeks and remains persistent may be indicative of streptococcal infection (strep throat) or laryngeal cancer[7],[8]

; - A persistent sore throat and otalgia (earache) may also indicate laryngeal cancer;

- A very high temperature, or patients feeling hot and shivery, may indicate glandular fever;

- Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) may indicate an abscess.

Patients who present with a sore throat and the following symptoms should call 999:

- Drooling, difficulty breathing and stridor (breathing that sounds high pitched and abnormal), as they may have epiglottitis (severe swelling of the back of the throat)[9]

.

It is also important to remember that patients with weakened immune systems (e.g. people with cancer or HIV) have a higher risk of complications and should be referred accordingly.

Diagnosis

A sore throat with no serious underlying cause will be self-limiting; therefore, patients need to be asked how long they have had a sore throat and its severity, as well as if they have experienced any other symptoms, to rule out more serious conditions (see Box).

It can be difficult to differentiate between a bacterial and viral cause based on a patient’s history and clinical findings. However, the clinical scoring tools FeverPAIN and Centor criteria can aid the detection of individuals who are more likely to have a streptococcal infection and, therefore, may benefit from antibiotics[1]

.

For FeverPAIN, patients receive one point for each of the five criteria they meet (i.e. fever in the past 24 hours, purulence [pus on tonsils], onset of illness of three days or less, severely inflamed tonsils and no cough)[10]

. A cumulative score of 4 or 5 is associated with a 62–65% likelihood of isolating Streptococcus

[4]

.

In the Centor criteria, 1 point is given for each of four criteria (i.e. tonsillar exudate, tender anterior lymphadenopathy [glands in the neck] or lymphadenitis [enlarged lymph nodes], history of fever [over 38°C] and absence of cough)[4]

. A cumulative score of 3 or 4 is thought to be associated with a 32–56% likelihood of isolating Streptococcus

[4]

.

To confirm the diagnosis of a bacterial infection, patients should be tested for group A streptococcal (GAS) infection with a rapid antigen detection test (RADT) and/or throat culture[11],[12]

.

Case studies

Case study 1: treating a sore throat in an adult

A 31-year-old female* presents in the pharmacy and asks to speak to the pharmacist. She has a sore throat and would like to buy medicine to ease the pain.

Assessment

Before recommending a product, it is important to ask questions to rule out a more serious condition and to provide the best level of care for this patient, including:

Sore throat characteristics

- How long have you had a sore throat?

- How severe is the sore throat?

- Are your glands tender?

Associated symptoms

- Are you experiencing hoarseness?

- Do you have a cough?

- Do you have a temperature?

Social history

- Do you smoke? If so, what type of tobacco do you smoke? How many cigarettes do you smoke per day? How long have you smoked for?

Medicine history

- Are you taking any regular medicine, both on prescription and over-the-counter (OTC)?

- Have you already taken any medicine to alleviate the symptoms?[5]

The patient explains that she has had the sore throat for around three days and has not taken any medicine yet as she thought her symptoms would have subsided by now. She mentions that the pain is moderate, but thinks it is enough to start taking something to help ease it. She has a mild cough that started around two days ago, no fever, does not take any other regular medicine, but socially smokes.

Diagnosis

Based on the information provided by the patient, it is likely that she has a self-limiting viral infection.

Advice and recommendations

She is advised to gargle warm salt water, ensure adequate hydration is maintained, rest and use non-medicated demulcent pastilles to soothe the throat and prevent the throat from being too dry[2],[13]

. In addition, she could use topical medicated throat products such as lozenges, sprays and mouthwashes that contain a type of anti-inflammatory and/or anaesthetic if required to help reduce the pain[1],[2],[14]

.

OTC analgesics, such as paracetamol 1,000mg up to four times per day or ibuprofen 400mg up to three times per day[1],[5],[15]

, will also help relieve her pain.

Smoking can aggravate a sore throat, so she is also provided with smoking cessation advice.

These treatments should benefit the patient because sore throat caused by a virus is self-limiting within 7–10 days and antibiotics are unlikely to make a difference[5]

. However, if the symptoms do not improve within this timeframe, she is advised to visit her GP. She is also advised that if she develops any breathing difficulties, dysphagia, severe pain, drooling, a muffled voice or becomes extremely unwell she should call 999[1]

.

Case study 2: treating a sore throat in a teenager

A 16-year-old male* presents to his local pharmacy because he has been experiencing a fever and a sore throat, which he thinks is getting worse.

Assessment

It is important to ask the patient some questions about their symptoms, including:

Sore throat characteristics

- How long have you had a sore throat?

- How severe is the sore throat?

- Are your glands tender?

Associated symptoms

- Are you experiencing hoarseness?

- Do you have a cough?

- Do you have a temperature?

- Do you have abdominal pain?

- Are you having difficulty breathing?

Social history

- Do you smoke? If so, what type of tobacco do you smoke? How many cigarettes do you smoke per day? How long have you smoked for?

Medicine history

- Are you taking any regular medicine, both on prescription and over the counter?

- Have you already taken any medicine to alleviate the symptoms?[5]

The patient explains that his symptoms have lasted for a few days and that he has also been quite tired recently, but thinks it is because he has been studying late at night for his upcoming exams. He occasionally gets headaches and has slightly swollen glands.

He also explains that he has not taken any medicines for his symptoms and, when questioned further about whether he has been in contact with anyone who may have had a sore throat, tonsillitis or a cold, he mentions he has been to some parties within the past few weeks and thinks he may have caught something from someone at one of these events.

It is important to ask the patient if he has been experiencing any abdominal pain and difficulty breathing as these are red flag symptoms that require prompt medical attention. If there is a yellowish discolouration of the skin or eyes, this is a major symptom indicative of jaundice, requiring timely referral[16]

.

Diagnosis

The patient confirms that he is not experiencing any other symptoms. It is therefore likely that he has glandular fever, which is caused by the Epstein–Barr virus. The incidence of this condition is highest in adolescents and adults[16]

.

Advice and recommendations

Since the patient has a fever, and seems to be getting worse, he is told to visit his GP. In the meantime, he can begin taking analgesic medicine, such as paracetamol 1,000mg up to four times per day or ibuprofen 400mg up to three times per day[17]

. He can also use medicated throat lozenges/sprays that contain numbing agents to help with the pain, in addition to gargling with salt water or an anaesthetic rinse, such as benzydamine hydrochloride[5],[14]

. In addition to this, he should ensure he gets adequate rest and hydration as it can take up to two to three weeks to fully recover.

Since the patient could still be contagious, he should be advised to observe good hand hygiene, as well as refraining from sharing food and utensils, and avoiding mouth-to-mouth contact with others, because the virus can be transmitted to an uninfected individual[16],[18]

.

Case study 3: treating a severe sore throat in a child

A concerned parent attends the pharmacy in need of advice about her eight-year-old son*, who has an extremely painful sore throat and cough. He is currently at home and in bed with a high temperature. On inspection of the back of his throat, his mother could see a creamy white matter on his tonsils. She explains that he has also not been eating very well as his throat is painful and he has become quite lethargic over the past few days. The sore throat started 5 days ago, and he has been in bed for the past 24 hours. She also mentions that the glands in her son’s neck appear to be swollen[5]

.

Advice and recommendations

The severity of his symptoms, and that he is struggling to eat, indicates that he is likely to have tonsillitis and should be referred to his GP. Although the patient is being referred to a GP, you can initially recommend an analgesic, such as paracetamol, possibly in a soluble or syrup form so it is easier to swallow. This would also be beneficial as an antipyretic for the patient’s fever[5]

. Caution should be taken when recommending that children gargle with salty water because there is a risk that they will choke or swallow it. Patients aged over five years with a sore throat, which is associated with cough, may benefit from honey and lemon juice in warm water (honey is not safe for children aged under one year)[19]

.

Tonsillitis could be caused by either a bacterial or viral infection, and therefore may or may not require an antibiotic. However, this patient has severe symptoms and the safest option is to prescribe phenoxymethylpenicillin as it is not viable to exclude a bacterial (streptococcal) infection at this point. The dose for the patient would be 250mg four times per day for ten days. Common side effects include diarrhoea, hypersensitivity, nausea, vomiting and skin reactions, and it is contraindicated in patients with known penicillin hypersensitivity[5],[20],[21]

. Erythromycin can be used if the patient is allergic to penicillin.

Recovery should take around a week and the patient should rest during this time, and continue taking paracetamol and their prescribed antibiotic. However, it should be explained that the patient’s mother that she should call 999 if the severe sore throat gets worse quickly or if the patient has difficulty speaking, swallowing or breathing.

*All case studies are fictional.

References

[1] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Sore throat (acute): antimicrobial prescribing guideline [NG84]. 2018. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng84/evidence/evidence-review-pdf-4723224013 (accessed September 2019)

[2] Farrer F. Sprays and lozenges for sore throats. South African Family Practice 2012;54(2):120–122. doi: 10.1080/20786204.2012.10874190

[3] Sore Throat (Pharyngitis). Harvard Health Publishing. 2017. Available at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/a_to_z/sore-throat-pharyngitis-a-to-z (accessed September 2019)

[4] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS). Sore throat — acute. 2018. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/sore-throat-acute (accessed September 2019)

[5] Blenkinsopp A, Paxton P & Blenkinsopp J. Symptoms in the Pharmacy: A Guide to the Management of Common Illness. Blackwell Publishing; 2005.

[6] Kenealy T. Sore throat. BMJ Clin Evid 2011;2014:1509. PMID: 21477389

[7] Shephard EA, Parkinson MAL & Hamilton WT. Recognising laryngeal cancer in primary care: a large case-control study using electronic records. BJGP 2019;69(679):e127–e133. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X700997

[8] Mayor S. Persistent sore throat may be a warning sign for laryngeal cancer, study suggests. BMJ 2019;364:l435. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l435

[9] NHS choice. Epiglottitis. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/epiglottitis (accessed September 2019)

[10] FeverPAIN. Available at: https://ctu1.phc.ox.ac.uk/feverpain/index.php (accessed September 2019)

[11] Advisory Group on Antibiotic Stewardship Programme in Primary Care, Chan AMW, Au WWY et al. Antibiotic management of acute pharyngitis in primary care. Hong Kong Med J 2019;25(1):58–63. doi: 10.12809/hkmj187544

[12] Ruppert SD & Fay VP. Pharyngitis: soothing the sore throat. Nurse Pract 2015;40(7):18–25. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000466498.57296.60

[13] Nathan A. FASTtrack: Managing Symptoms in the Pharmacy. Pharmaceutical Press: RPS Publishing; 2008.

[14] eMC. Summary of characteristics. Difflam 0.15% w/v Sore Throat Rinse. 2018. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/9258/smpc (accessed September 2019)

[15] ESCMID Sore Throat Guideline Group, Pelucchi C, Grigoryan L et al. Guideline for the management of acute sore throat. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;Suppl 1:1–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03766.x

[16] Ebell MH. Epstein-Barr virus infectious mononucleosis. Am Fam Physician 2004;70(7):1279–1287. PMID: 15508538

[17] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS). Glandular fever (infectious mononucleosis). 2015. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/glandular-fever-infectious-mononucleosis#!topicSummary (accessed September 2019)

[18] Lennon P, Crotty M & Fenton JE. Infectious mononucleosis. BMJ 2015;350:h182. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1825

[19] NHS.UK. Honey, not antibiotics, recommended for coughs. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/news/heart-and-lungs/honey-not-antibiotics-recommended-coughs (accessed September 2019)

[20] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and British National Formulary. Penicillins. 2019. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/penicillins.html (accessed September 2019)

[21] eMC. Summary of product characteristics. Penicillin VK Tablets 250 mg. 2019. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1754/smpc (accessed September 2019)