Shutterstock.com

By the end of this article, you should be able to:

- Identify the main features and symptoms of cardiac chest pain to differentiate between stable angina, unstable angina and acute coronary syndrome;

- Understand the appropriate diagnostic tests and when to use them, including ECG and troponin assays, for evaluating chest pain in a primary care setting;

- Apply risk assessment tools, such as the ‘QRISK3’ score, to evaluate the likelihood of coronary artery disease and guide management decisions;

- Develop a management plan for patients presenting with chest pain, including referral criteria for specialist care and strategies for patient education and follow up.

Cardiac chest discomfort can be caused by valvular disease, such as moderate to severe aortic stenosis, spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD), pericarditis, myocarditis and aortic dissection, but most commonly is caused by coronary artery disease (CAD) restricting blood flow to the myocardium, thus myocardial ischaemia1.

Myocardial ischaemia is often described as ischaemic heart disease (IHD). Cardiac chest discomfort can be a red flag for a cardiac issue, particularly in acute presentations. Between 5% and 14% of individuals diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) die within the year following their diagnosis, with approximately half of these fatalities occurring within the first four weeks2. In 2022, IHD was the leading cause of male mortality, accounting for 13.3% of male deaths in England and Wales3. The leading cause of death in females in England and Wales was dementia, with IHD, which ranked second, accounting for 7.2% of all deaths3. In comparison, malignancy in both genders ranks lower — 5.1% and 4.8%, respectively — despite the high public profile of cancer3.

The word ischaemia derives from the Greek word ‘iskhaimos’, which means ‘stopping blood’4. Coronary ischaemia can result in angina, which usually manifests as chest pain and is often described as a discomfort, heaviness, tightness or pressure5. Angina is a symptom of myocardial ischaemia but is not a disease itself.

The focus of this article will be identification of myocardial ischaemia caused by coronary artery disease. It will demonstrate how pharmacists and other healthcare professionals in primary care can determine whether discomfort is non-cardiac, outline the red flags to look out for and summarise recommended referral pathways and management.

Stages of myocardial ischaemia

There are broadly two stages of myocardial ischaemia presentations: stable angina6 and acute coronary syndrome (ACS)7, which includes unstable angina and certain classifications of myocardial infarction.

Stable angina is predictable chest pain typically triggered by exertion or stress and relieved by rest. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a spectrum of conditions, including unstable angina, which is unpredictable and may occur at rest or with minimal exertion, and often signifies a more severe underlying issue.

A patient may present to primary care at any of these stages but commonly there are warning signs of a heart attack. The majority of patients show initial signs of stable angina, which will reduce the chance of advancing to more serious presentations of myocardial ischaemia, if they are identified and managed early.

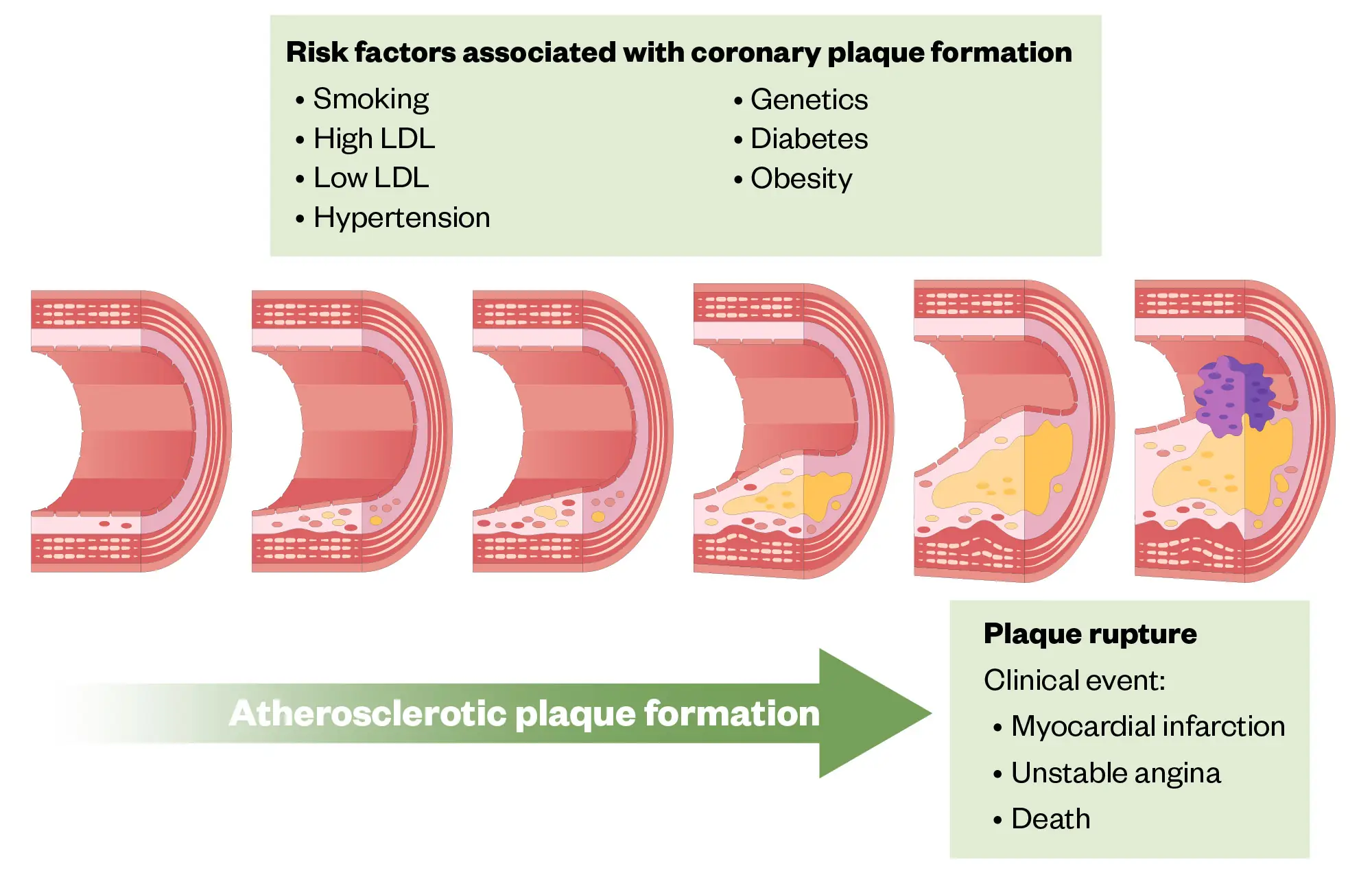

Figure 1 shows the risk factors associated with coronary plaque formation and the associated physiological changes. When the plaque impairs blood flow, the presentation can move from stable angina to myocardial infarction, and is often caused by plaque rupture8.

Shutterstock.com

Atypical cardiac chest pain phenomena

There are other conditions that can also cause chest pain and these have different diagnostic characteristics. The symptoms associated with coronary artery spasm (Prinzmetal angina), spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) and severe valve disease can all present with chest pain or discomfort. All three result from a reduction in myocardial blood flow but the mechanisms vary. While coronary artery spasm and SCAD are characterised by temporary, often unpredictable chest pain (resulting from artery constriction or dissection), severe valve disease may cause symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath and fatigue, owing to the heart’s impaired ability to pump blood effectively.

Coronary artery spasm is more common in women and more prevalent with recreational drug use, particularly cocaine9. The pain of a coronary artery spasm is often more acute than that of exertional angina. SCAD is more common in menstruating women and often presents as a myocardial infarction, accounting for 25% of all heart attacks in women aged under 50 years10.

The symptoms associated with valve disease most closely mimic exertional angina. The disease of the aortic valve in particular limits the flow of blood from the ventricle through the aortic valve. Aortic stenosis results in the heart having to work harder to open the valve so the muscle grows in size, increasing demand on the arteries, which are in turn underfilled because of reduced flow past the aortic valve. This obviously makes exertion more problematic. Left untreated, this condition can cause irreversible heart damage, ultimately resulting in heart failure.

It is beyond the scope of this article to explore these presentations further, but it is well described in the literature11–13. Practitioners should be aware of these conditions; however, they are often challenging to diagnose in primary care settings owing to their complexity. Initial identification may be possible through basic questioning about chest pain, but definitive diagnosis usually requires further specialised testing and evaluation.

Assessment for typical angina

Diagnosing angina based solely on symptom history can be challenging so careful questioning is crucial. The likelihood of angina should be assessed in the context of the patient’s risk factors (see Figure 1) and overall probability of developing cardiovascular disease.

The QRISK3 score, which is commonly used in primary care and listed in the British National Formulary, is aimed to help evaluate this risk14. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on assessment for chest pain suggests criteria for the determination that a chest pain is angina15. This has been adapted in all the South West London rapid access chest pain clinics (RACPCs). If there are less than two features listed below, then the referrer is advised that the referral is inappropriate:

- Constricting discomfort in the front of the chest, or in the neck, shoulders, jaw or arm;

- Precipitated by physical exertion;

- Relieved by rest or administration of glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) in approximately five minutes.

It is noteworthy that those with myocardial ischaemic symptoms (angina) will often deny chest “pain” and instead use any word but this. The term discomfort in this tool is used advisedly.

Location and assessment of discomfort

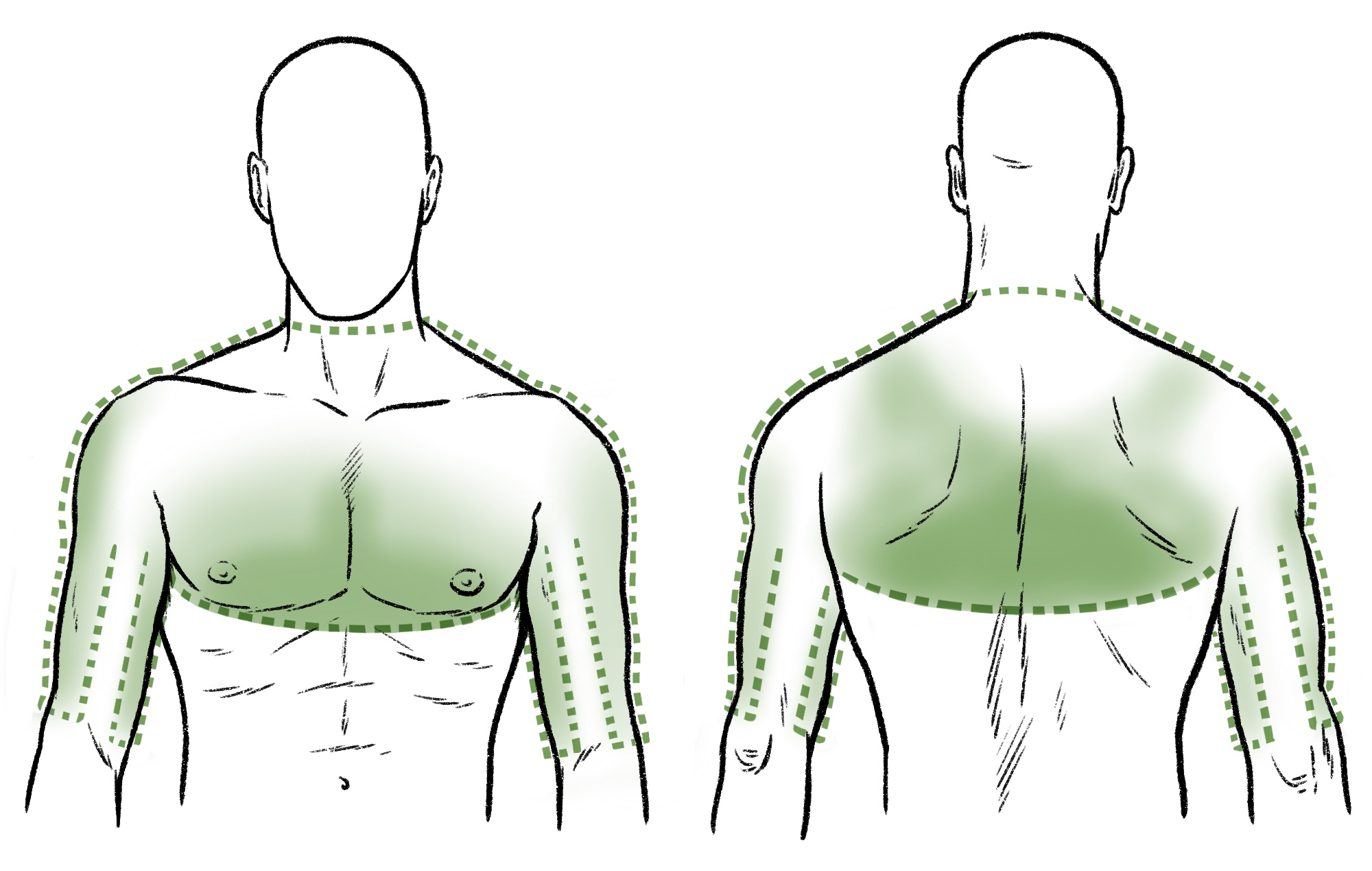

The description of angina pain or discomfort can vary but its location rarely does. See Figure 2 for the common sites.

In the assessment of discomfort a useful and popular tool is using the mnemonic SOCRATES16. This refers to Site, Onset, Character, Radiation, Alleviation, Time, Exacerbation and Severity. This will help the practitioner to employ a methodical approach to chest pain assessment.

The Pharmaceutical Journal

- Site (position) — The first tool to help you differentiate cardiac chest discomfort is the variation in location. Unilateral left sided presentation is common but unilateral right sided presentation is highly unlikely to be cardiac17. The sole presence of left sided chest discomfort is highly predictive of anginal chest pain. Anginal chest discomfort may present bilaterally or centrally or the discomfort may be in the upper back, again central or across the whole region or left scapula;

- Onset — This typically occurs with exertion, usually gradual onset;

- Character — This is usually described as heavy, crushing, tight, constricting, less often burning. More commonly females describe indigestion-type symptoms so be wary of this18;

- Radiation — This may radiate to the left side or down both sides or to jaw or lower teeth. A patient may only present with pain in the tooth or left arm and only on exertion;

- Associated factors — Angina can be associated with breathlessness, sweating or belching;

- Timing/duration — Discomfort relieved by rest within 5–15 minutes. If longer, suspect either a worsening of angina or alternate cause of chest discomfort. Constant pain is a sign the problem is not angina;

- Exacerbating factors — This is provoked by exertion and worsened by continuing same level of exertion;

- Severity — This is usually a discomfort at the stable stage. Not a pain, it is mild, not troubling. As it is mild, it is regularly missed and presents late. More advanced disease results in more severe pain. Those suffering a myocardial infarction will often describe very strong debilitating pain, which they can describe as “the worst pain ever”.

Other signs that the patient’s chest pain is not angina include:

- Pain worse on inspiration;

- Pain worse on palpation;

- Pain relieved or provoked by movement of upper body;

- Pain on eating.

Box 1: The importance of effective questioning when assessing chest pain

A study in 2023 measured the effectiveness of asking patients experiencing chest pain who reported to an emergency department the following questions:

- Did the chest pain occur at the left/middle chest?

- Did the chest pain radiate to the back?

- Was the chest pain provoked by activity and relieved by rest?

- Was the chest pain provoked by food ingestion, positional changes, or breathing? (This is a negative question).

The study involved 164 patients and results showed a 92% sensitivity, 84% specificity, 85% positive predictive value and 86% negative predicted value19.

The following case study provides an opportunity to apply these assessment principles to a patient scenario.

Case study: initial assessment of a patient experiencing chest pain

Mr A, aged 50 years, was seen in a nurse-led rapid access chest pain clinic (RACPC) following a referral from his GP. He was seen within two weeks of referral, as per National Standard Framework for Coronary Heart Disease20.

Mr A smoked 20 cigarettes a day for 25 years and his father had a heart attack aged 55 years (he is still alive having had a coronary artery bypass operation). Mr A presented with chest discomfort at rest.

Following further questioning using the ‘SOCRATES’ approach, it is determined that the symptoms were initially only experienced when walking but his sleep had been disturbed the previous night, with the same pain experienced but with much worse severity.

SOCRATES assessment:

Site — Central chest;

Onset — With exertion but newly at rest;

Character — Discomfort, heavy;

Radiation — None with exertion but radiating to left jaw the night before;

Associated factors — None;

Timing — Between five minutes if it comes on with exertion and relieved by rest; one hour when experienced the night before at rest. Pain has been present for eight weeks;

Exacerbating — Exertion or eating and then walking (Post prandial angina)21;

Severity — Normally mild discomfort but a very strong pain experienced in the middle of the night.

Observations were taken, showing a normal blood pressure measurement for the patient and unremarkable oxygen levels and heart rate. Heart sounds demonstrated no abnormalities and the ECG showed no ST segment changes, which is the main indicator of ischaemia. Troponin I assay was ordered.

Evaluation:

There are many tools to determine likelihood of disease but the obvious risk factors for Mr A were family history of heart disease and being a smoker. The QRISK3 score for Mr A indicated a 15.5% chance of having a heart attack or stroke within the next ten years.

As the onset of symptoms had changed, the nurse decided that Mr A had stable angina, which had deteriorated to unstable angina with post-prandial features.

Diagnosis and treatment:

Mr A had further ECG and blood tests which supported a diagnosis of non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. The patient was admitted to hospital and had a stent to the right coronary artery. The early intervention contributed to the preservation of myocardial function, demonstrated on echocardiography two weeks following the event.

In cases where the initial assessment suggests the patient may be experiencing cardiac chest pain, an ECG and a troponin I assay will be performed. These tests are crucial for confirming the diagnosis and determining the underlying cause of the symptoms, which will help guide the subsequent management plan. These diagnostic tools allow us to categorise the presentation as either ST or non-ST elevation MI22. ST elevation refers to a sign on the ECG whereas the troponin I assay will indicate myocardial cell death. Unstable angina typically refers to patients who experience concerning symptoms but do not have elevated troponin levels. Despite the absence of elevated troponin, unstable angina is associated with a risk of non-fatal heart attacks comparable to that of patients with confirmed myocardial infarction23. For more on ECG interpretation, see the article ‘Interpretation of electrocardiograms‘.

NICE recommends immediate coronary intervention (revascularisation) for those with ongoing symptoms24. In the case study above, Mr A’s symptoms resolved quickly but intervention is still recommended. The timing of these interventions should be determined by the risk of future events or mortality24. For more detail, see NICE guidance on the management of ACS and recent onset chest pain24,25.

Again using the example of Mr A from the case study, we are able to show how the ‘SOCRATES’ method provides an opportunity to work through the main differentials of cardiac chest pain and rule out a number of other cardiac conditions (see Table)26–28.

Red flags

If any of the following are suspected, emergency care should be provided including a 999 call:

- Aortic dissection;

- Myocardial infarction;

- Haemodynamic compromise is present (symptoms include cool clammy peripheries, rapid breath, reduced blood pressure and loss of pallor).

Non cardiac causes of chest pain

While the focus of this article is on identification of cardiac causes of chest pain, it is also helpful to briefly consider non-cardiac causes. Being able to rule these out enables the practitioner to have more confidence in a cardiac diagnosis.

Gastrointestinal causes

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disorder (GORD) is a very common cause of chest pain. Other characteristics and features include: bad breath, bad taste in mouth, stomach pain, trouble swallowing and vomiting. For more information on GORD, see the article ‘Case-based learning: GORD in adults’.

Gallbladder disease (cholecystitis) can also cause chest pain29. Characteristics include pain localised to right upper abdomen, as well as pain that radiates to the back chest and shoulder that is worse after a heavy meal.

Respiratory causes

Pulmonary embolus also causes chest pain30. It is often associated with breathlessness and hypoxia or cyanosis, may have haemoptysis, feeling lightheaded, sweating, shortness of breath, leg pain or leg swollen on one side and inspirational chest pain. The likelihood of pulmonary embolus is increased with recent periods of inactivity, such as long-distance travel.

Chest pain is also a symptoms of chest infection/pneumonia. Presentation is similar to pulmonary embolus but without unilateral leg swelling. Other symptoms include fever, sputum that appears infected, rapid shallow breathing and confusion (in older people).

Muscular skeletal causes

- Costochondritis — Inflammation of the costochondrial muscles. This is typified by discomfort on palpation. It is continuously present on provocation of pressing and inspiration;

- Trauma or degenerative changes — History present of mechanical trauma or discomfort on movement or pressing. Imaging may be needed31.

Assessment and management of suspected cardiac ischaemia in primary care settings

Once the practitioner suspects that the discomfort could be myocardial ischaemia, the management of cardiac chest pain in the community is limited by the resources available. When a patient presents with chest discomfort there are two important things that can help with the decision-making as to appropriate next steps: careful questioning and establishing the vital signs. The immediate priority is to determine whether the patient needs emergency help. Below is a list of red flags that will assist with this24.

Box 2: Red flags for angina that could indicate instability (adapted from NICE)

- Newly occurring at rest;

- Not relieved by rest or GTN within 15 minutes;

- Increasing in frequency or coming with less provocation;

- Associated with nausea and vomiting, marked sweating, cool peripheries, breathlessness or particularly a combination of these.

Obtain a brief relevant medical history, (including cardiac history and symptoms history) and consider the likelihood of disease based on cardiovascular risk factors and tools, such as QRISK score. If possible, obtain a full set of vital signs (e.g. blood pressure, oxygen levels, heart rate, ECG).

The ‘Look, Listen, Feel’ approach to physical assessment can also provide valuable information:

LOOK — How does the patient look?

Colour, pallor, breathlessness, rapid breathing, clutching chest. Use your tools for signs of haemodynamic compromise (considering the patients norm if available).

LISTEN — What does the patient say?

Careful questioning, history taking. Use SOCRATES to establish risk especially onset, timing and severity. Make sure you cover all points and think about your differential diagnoses, use your red flags (below) to determine urgency. What is the likelihood and is there a history of angina?

FEEL — Is the patient clammy, cool or warm?

For more on physical assessment approaches see: ‘Introduction to clinical assessment for prescribers’.

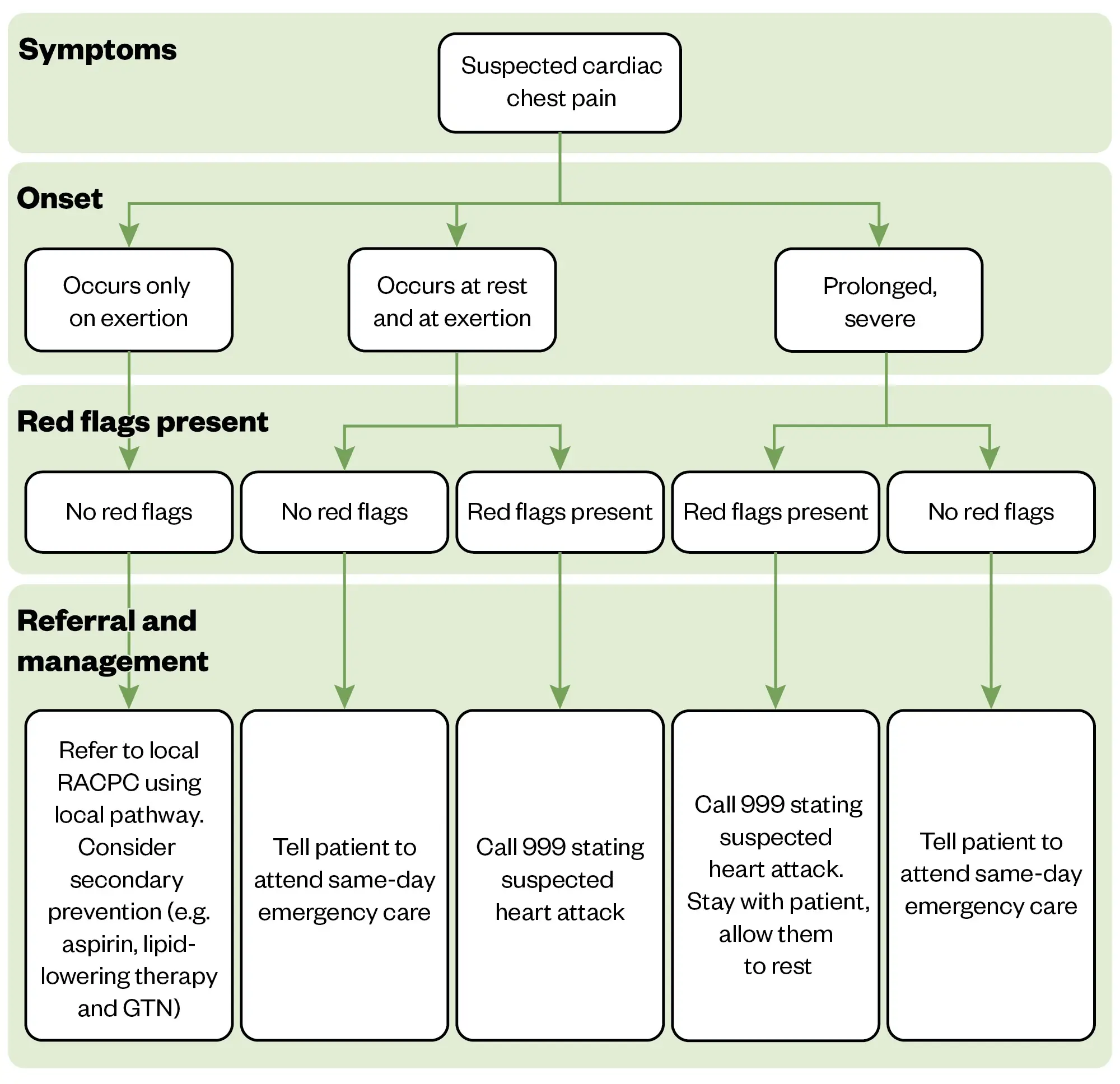

Figure 3 provides a summary of action to take depending on the nature of symptoms.

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Safety netting advice

If the assessment concludes that non-urgent assessment is required, it is important to provide the patient with clear safety netting advice. Make sure that they understand what red flags to look for and what action to take if their condition or symptoms change.

For more information on safety netting and red flag symptoms see:

- ‘How to provide patients with safety-netting advice’;

- ‘How to identify red-flag symptoms and refer patients appropriately‘.

Summary

Effective assessment and early intervention are key when responding to cardiac chest pain and the steps practitioners should take can be easily memorised using the mnemonic SPURS:

- SOCRATES assessment (to gather history of symptoms and work through key differentials)

- Physical assessment and vital signs (assess haemodynamic status)

- Urgency (establish if red flags are present)

- Risk factors (estimate likelihood of disease)

- Signpost appropriately (using Figure 3 as a guide).

Useful resources and further reading

- Recommendations for anginal drug treatment, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence;

- ‘Acute coronary syndrome: diagnosis and treatment‘, The Pharmaceutical Journal;

- ‘Management of stable angina‘, The Pharmaceutical Journal.

- 1.Shahjehan R, Bhutta B. statpearls. Published online August 17, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564304/

- 2.Sarkees M, Bavry A. Acute coronary syndrome (unstable angina and non-ST elevation MI). BMJ Clin Evid. 2009;2009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19445778

- 3.Deaths registered in England and Wales. Office for National Statistics. 2022. Accessed October 2024. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsregistrationsummarytables/2022#:~:text=Dementia%20and%20Alzheimers%20disease%20was,for%2010.3%25%20(59%2C356%20deaths)

- 4.Boden WE, Kaski JC, Berry C. Reprising Heberden’s description of angina pectoris after 250 years. European Heart Journal. 2022;44(19):1684-1686. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac643

- 5.Diagnosis and management of stable angina. Pharmaceutical Journal. Published online 2021. doi:10.1211/pj.2021.1.115357

- 6.Ambrose JA, Singh M. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease leading to acute coronary syndromes. F1000Prime Rep. 2015;7. doi:10.12703/p7-08

- 7.Willerson J, Yao S, Ferguson J, Anderson H, Golino P, Buja L. Unstable angina pectoris and the progression to acute myocardial infarction. Role of platelets and platelet-derived mediators. Tex Heart Inst J. 1991;18(4):243-247. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15227406

- 8.McCord J, Jneid H, Hollander JE, et al. Management of Cocaine-Associated Chest Pain and Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2008;117(14):1897-1907. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.107.188950

- 9.Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed October 2024. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17503-spontaneous-coronary-artery-dissection-scad

- 10.Williams S, Lindsay S. Syncope and chest pain at rest in aortic stenosis. Br J Cardiol. 2003;(10):143-144. https://bjcardio.co.uk/2003/03/syncope-and-chest-pain-at-rest-in-aortic-stenosis/

- 11.Caverley ZR, Tam LM. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection. JAAPA. 2023;36(12):8-13. doi:10.1097/01.jaa.0000991340.13787.3c

- 12.de Luna AB, Cygankiewicz I, Baranchuk A, et al. Prinzmetal Angina: ECG Changes and Clinical Considerations: A Consensus Paper. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2014;19(5):442-453. doi:10.1111/anec.12194

- 13.QRISK®3-2018 risk calculator. QRISK. Accessed October 2024. https://www.qrisk.org/index.php

- 14.How should I assess someone with stable chest pain? . National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Accessed October 2024. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/angina/diagnosis/assessment-of-stable-chest-pain/

- 15.Ford C. Adult pain assessment and management. Br J Nurs. 2019;28(7):421-423. doi:10.12968/bjon.2019.28.7.421

- 16.Right-side chest pain. Cleveland Clinic. 2020. Accessed October 2024. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/25070-right-side-chest-pain

- 17.DeVon HA, Ryan CJ, Ochs AL, Shapiro M. Symptoms Across the Continuum of Acute Coronary Syndromes: Differences Between Women and Men. American Journal of Critical Care. 2008;17(1):14-24. doi:10.4037/ajcc2008.17.1.14

- 18.Lukitasari M, Apriliyawan S, Manistamara H, Sella YO, Rohman MS, Jonnagaddala J. Focused Chest Pain Assessment for Early Detection of Acute Coronary Syndrome: Development of a Cardiovascular Digital Health Intervention. gh. 2023;18(1):18. doi:10.5334/gh.1194

- 19.National Standard Framework for Coronary Heart Disease. NHS. 2020. Accessed October 2024. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7b03a7e5274a319e77c60a/National_Service_Framework_for_Coronary_Heart_Disease.pdf

- 20.Baliga RR, Rosen SD, Camici PG, Kooner JS. Regional Myocardial Blood Flow Redistribution as a Cause of Postprandial Angina Pectoris. Circulation. 1998;97(12):1144-1149. doi:10.1161/01.cir.97.12.1144

- 21.Clinical Knowledge Summary: MI, secondary prevention, what is it? . National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Accessed October 2024. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/mi-secondary-prevention/background-information/definition/

- 22.Puelacher C, Gugala M, Adamson PD, et al. Incidence and outcomes of unstable angina compared with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Heart. 2019;105(18):1423-1431. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314305

- 23.Acute Coronary Syndrome (NG185). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2020. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng185/chapter/Recommendations#nstemi-and-unstable-angina-early-management

- 24.Recent-onset chest pain of suspected cardiac origin: assessment and diagnosis. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Accessed October 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg95

- 25.Symptoms and diagnosis of pericarditis. American Heart Association. Accessed October 2024. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/pericarditis/symptoms-and-diagnosis-of-pericarditis

- 26.Myocarditis. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed October 2024. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22129-myocarditis

- 27.Aortic aneurysm, dissection and rupture. British Heart Foundation. Accessed October 2024. https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/conditions/aortic-aneurysm-dissection-and-rupture

- 28.Rivas J. Digestive causes of chest pain: what you need to know. Rivas Digestive Center. Accessed October 2024. https://www.johnrivasmd.com/blog/digestive-causes-of-chest-pain-what-you-need-to-know

- 29.Daliparty VM, Amoozgar B, Razzeto A, Ehsanullah SUM, Rehman F. Cholecystitis Masquerading as Cardiac Chest Pain: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22. doi:10.12659/ajcr.932078

- 30.Railton D. What Could Cause Chest Pain. Medical News Today. Accessed October 2024. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321650#lung-problem

- 31.Gillen C, Goyal A. statpearls. Published online December 19, 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559016/

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

If pain is Newly occurring at rest;

Not relieved by rest or GTN within 15 minutes;

Increasing in frequency or coming with less provocation;

Associated with nausea and vomiting, marked sweating, cool peripheries, breathlessness or particularly a combination of these.

….

So gtn spray or tabs could be obtained from pharmacies if appropriate and proviso goto call for further help if experience above symptoms