Shutterstock.com

When Debbie Barr was diagnosed with epilepsy aged 26 years, she had no immediate plans to become pregnant. However, because she was of childbearing age, her doctor prescribed anti-epileptic medicines considered to be safe for a developing foetus: first she was given lamotrigine (Lamictal; GlaxoSmithKline), then levetiracetam (Keppra; UCB Pharmaceuticals Inc.) for better seizure control.

However, levetiracetam did not successfully eliminate her tonic-clonic seizures, during which she would lose consciousness and sometimes fall.

As a result, when Barr did become pregnant three years later, she lived in constant fear of hurting herself or her unborn child during a seizure. As a precaution, Barr made sure she was never alone during both of her pregnancies. That way her companion — usually her husband, mother, or sister — could reassure her of what had happened if she had a seizure.

Barr had multiple seizures during her pregnancy, and each time she visited the emergency department to check that the baby was still moving and that its heart was still beating.

“Pregnancy was terrifying,” says Barr, now a mother of two healthy children. “But you just kind of block it out and hope for the best because there’s very little you can do about it.”

A balancing act

Women with epilepsy face a conundrum when choosing medicines to control their seizures. During pregnancy, seizures pose a danger to the mother and baby alike, through injury, preterm delivery or even death. But some anti-epileptic medicines are also associated with risks to the developing foetus.

Most notorious for these risks is valproate — a very effective anti-epileptic medicine that is linked to congenital malformations and developmental delays in children born to mothers taking the drug during pregnancy.

In 2018, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) introduced new regulatory guidance stating that if valproate is the only treatment option for women of childbearing age, they must be signed up to a pregnancy prevention programme (PPP). Women on a PPP receive contraception, an annual review with their specialist and the materials needed to understand the risks posed by valproate. This is a stronger regulatory stance than found in previous warnings, which merely advised that there was a risk of birth defects from the medicine.

And, with valproate use downgraded, the need for alternatives has become more acute; every year an estimated 2,500 women with epilepsy have a baby in the UK.

“These are important, live issues that we need to be thinking about,” says Sanjay Sisodiya, a professor of neurology at University College London and director of genomics at the Epilepsy Society.

To identify safer alternatives to valproate, the MHRA carried out a comprehensive review of non-valproate anti-epileptic medicines in 2019, and released its report in January 2021[1]. The report highlighted lamotrigine and levetiracetam as safe medicines for women during pregnancy, both in terms of birth defects and neurodevelopmental delays in their babies.

But dilemmas remain. Epilepsy is a varied condition and medicines that work for one person may not work for another. Seizure control during pregnancy can be a moving target, requiring increasing doses or changes to medicines. Furthermore, it remains unclear exactly how anti-epileptic drugs disrupt foetal development, adding uncertainty about the best way to offset the risks (see Box).

It’s a very individual discussion, and different women and their partners will have different views

Sanjay Sisodiya, director of genomics at the Epilepsy Society

However, concerted awareness-raising among prescribers about the safer alternatives could help protect women.

The MHRA report promises to guide clinical decision-making; however, the choice is, ultimately, a very personal one, in which a woman weighs her tolerance for seizures and the health of her baby.

“There isn’t a formula for this,” Sisodiya says. “It’s a very individual discussion, and different women and their partners will have different views.”

Box: The underlying mechanisms

Knowing how to mitigate risks from anti-epileptic medicines is difficult because the reasons for drug teratogenicity remain unclear.

One theory is that the medicines trigger inappropriate cell death. Programmed cell death is a regular part of brain development, but animal studies indicate that anti-epileptic medicines can trigger this to occur at an increased rate[2].

Another hypothesis is that the drugs interfere with absorption of folate, a vital nutrient in the early stages of foetal development. Women in the general population often take folate supplements to stave off birth defects, but it is not clear that this works for women with epilepsy. Some data suggest high doses of folate can help protect adverse cognitive effects in babies of women taking anti-epileptic medication during pregnancy, but the data are inconsistent and confounding factors are abound[3,4].

“The bottom line is that we don’t know if folate supplementation is reducing the risk of malformations that are caused by the anti-epileptic medications,” says Torbjörn Tomson, a professor of neurology at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

There are also theories around genetics. Sisodiya and colleagues are exploring maternal genetics to see if mothers carry variants that predispose them, when taking an anti-epileptic medicine, to having a child with birth defects. This project is part of a collaboration called EpiPGX, which is funded by the European Commission, to find genetic variants that can help inform medicines strategies for people with epilepsy.

“That’s something that we’re exploring because it would mean you might be able to identify that someone is at greater risk or lesser risk on a particular drug or particular dose. And therefore you could try to manage that appropriately,” says Sanjay Sisodiya, a professor of neurology at University College London and director of genomics at the Epilepsy Society.

Recently, EpiPGX unveiled evidence suggesting that anti-epileptic medicines do not introduce new mutations to the foetus[5].

Safety in numbers

The teratogenic effects of anti-epileptic medicines have clouded the field for at least 50 years, with the earliest reports linking phenytoin and phenobarbital to congenital malformations, such as cleft lip, cleft palate, malformed limbs, cardiac abnormalities and neural tube defects.

When valproate was licensed in the 1970s, its teratogenic potential was already recognised, but the risks were not quantified well enough to guide clinicians, who — as recently as 20 years ago — were simply advised to prescribe the medicine that best controlled seizures during pregnancy[6].

However, the risks associated with doing nothing are significant. Barr was right to be concerned; a tonic-clonic seizure during pregnancy can injure the mother and her baby. Seizures in unmedicated women with epilepsy are also associated with a greater risk of preterm delivery and low birth weight[7].

There as an influx of new anti-epileptic medicines in the 1990s, including lamotrigine, levetiracetam and topiramate. These drugs brought varied mechanisms of action to the control of seizures — both focal, in which aberrant electrical activity involves only part of the brain, and generalised, which involves the whole brain and results in a loss of consciousness.

There was a great need to gather data on these medications to provide a basis for informed decisions

Torbjörn Tomson, professor of neurology at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm

The introduction of these medicines also brought questions about whether they, like their predecessors, were teratogenic. This triggered the establishment of several registries around the world to track foetal outcomes in women taking the medicines during pregnancy, including the International Registry of Antiepileptic Drugs and Pregnancy (EURAP) and the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy register, as well as equivalent registries in India, Australia and North America.

“There was a great need to gather data on these medications in a systematic way to provide a basis for informed decisions,” says Torbjörn Tomson, a professor of neurology at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm and member of the study group for EURAP, the largest epilepsy-dedicated registry.

Established in 1999, the primary aim of EURAP is to compare the safety of different antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy with respect to the risk of birth defects.

With their patients’ permission, participating neurologists voluntarily enter information about their pregnancies, including the medicines they are taking at the time of conception. With time, the sample size has grown large enough — now 27,000 pregnancies across 45 countries — to detect real signals.

In 2019, EURAP reported a decrease in valproate prescriptions in 2000–2013, and a 27% decrease in congenital malformation prevalence that seemed to be owing to this change in prescription numbers[8].

While EURAP focuses exclusively on congenital malformations, other registries have tracked cognitive outcomes in children, which takes more time and effort to ascertain. For example, valproate has been linked to reduced IQ in children aged six years, which raises a question about the subtle effects of non-valproate drugs on cognition[9].

Comparing risks

In 2018, NHS Digital and the MHRA established a nationwide valproate registry, which includes prescribing data from the NHS Business Services Authority, and links it to the Maternity Services Data Set and Hospital Episode Statistics data in England.

The initial purpose of the registry was to track the effects of valproate on pregnancies and outcomes, both in terms of birth defects and neurodevelopmental delays. Patient entry is automatic and anonymous. In the future, it will also include non-valproate medicines.

We are trying to make sure that those numbers of women using valproate during pregnancy are absolutely minimised

Sarah Branch, director of vigilance and risk management of medicines at the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency

The monitoring has already borne fruit, as detailed in a report published in February 2021, which showed that valproate use during pregnancy in the UK remains higher than expected[10].

“We are trying to make sure that those numbers are absolutely minimised,” says Sarah Branch, director of vigilance and risk management of medicines at the MHRA.

To identify safer alternatives, the MHRA undertook a review in 2019 of non-valproate medicines widely used in the UK and their safety during pregnancy, drawing from clinical and non-clinical data[1].

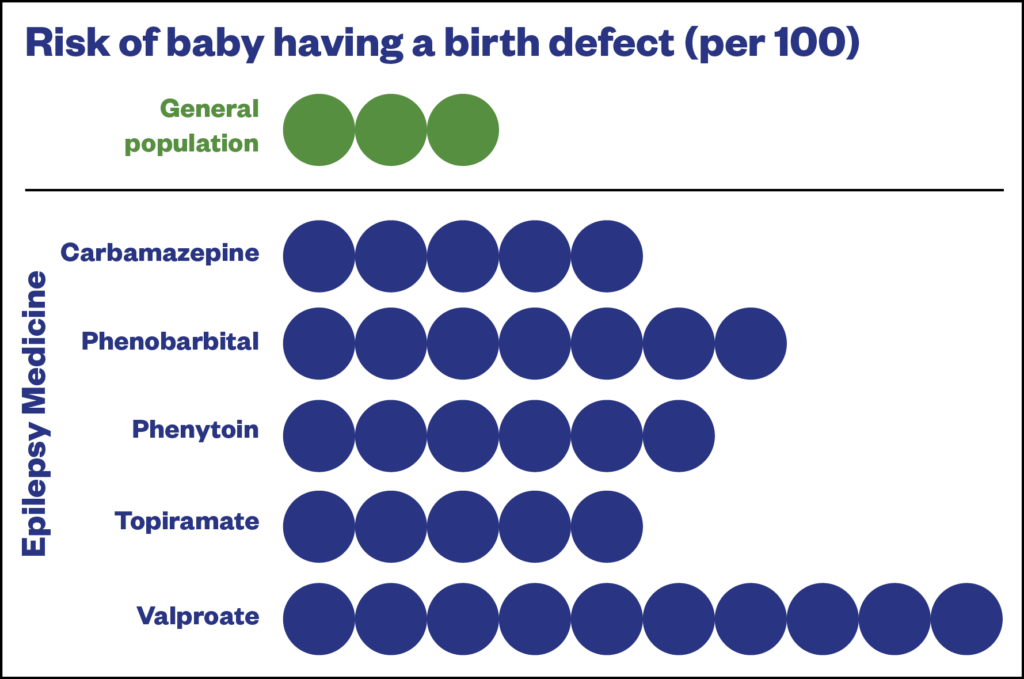

The report, published in January 2021, identified lamotrigine and levetiracetam as safe drugs to use during pregnancy; they were not associated with an increase in birth defects compared with the number occurring in the general population. Other drugs had increased prevalence of birth defects but less than that found for valproate (see Figure).

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency

For cognitive difficulties, the report concluded that phenobarbital and phenytoin were associated with increased risk, although the risk was not as high as that for valproate. Carbamazepine, lamotrigine and levetiracetam did not show an increased risk, although these conclusions were based on less data.

The report does not spring any surprises and provides a quantitative comparison of risks that could guide medicine choice. “It’s an important initiative,” Tomson says, adding that the findings are in line with an earlier EURAP study, which compared eight different anti-epileptic medicines and found lamotrigine, levetiracetam and oxcarbazepine were not associated with increased risk of congenital malformations[11].

Tomson notes, however, that the dose dependence of some drugs is overlooked in the report’s concluding statements. For example, he says, a high dose of lamotrigine — a drug deemed safe during pregnancy — is associated with a similar prevalence of malformations as a low dose of carbamazepine.

The report was also accompanied by a patient safety leaflet summarising the findings[12]. “We have feedback that clinicians are already finding it helpful and able to share with women,” Branch says.

Overall, the findings indicate that women with epilepsy of childbearing potential should be managed, as much as possible, on lamotrigine or levetiracetam. And, given the unplanned nature of many pregnancies, this should start as soon as possible prior to pregnancy.

In May 2021, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence reviewed and amended its recommendations on carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, pregabalin, topiramate and zonisamide in line with the MHRA’s updated safety advice on anti-epileptics in pregnancy.

However, simply substituting lamotrigine or levetiracetam into a patient’s treatment plan is not a guaranteed path to safety. As in Barr’s case, these drugs may not fully control seizures, and tweaking the dosage, or adding medicines, is a trial and error process that can take months to get right.

In addition, some patients will develop dangerous hypersensitivities to these medicines, and even if a woman appears to be stable on a safe drug prior to pregnancy, this can change during pregnancy[13].

“There may be a list of drugs that you would think would be appropriate for this person’s epilepsy, but that has to be tempered by the risks they carry and by a woman’s choice in terms of starting a family,” Sisodiya explains.

There may be a list of drugs you think would be appropriate, but that has to be tempered by the risks and a woman’s choice

Sanjay Sisodiya, director of genomics at the Epilepsy Society

Protecting women and children

Without a definitive understanding of teratogenic mechanisms, campaigns to raise awareness about safe alternative medicines will help offset some of the risk; the #SafeMumSafeBaby campaign, started by the Epilepsy Society in February 2021, aims to do just this.

Branch, who trained as a pharmacist, says that pharmacists can make a big difference to women like Barr, by ensuring they have all of the relevant information at their fingertips.

Pharmacists can help ensure that women are receiving an annual review with their neurologist; taking appropriate contraception; planning to seek advice about the most appropriate medicines if they are thinking about becoming pregnant; and have received the patient safety leaflet that was developed as part of the MHRA report.

“That kind of support would be welcomed from pharmacists,” Branch says.

While Barr recognises all of the newly available information as a positive improvement, she is glad to have the complicated decision making behind her. She is now taking lacosamide (Vimpat; UCB), which gives her good seizure control.

“It’s great not to have to choose medication based on those other kinds of factors now,” Barr says. “It’s basically about what’s going to work best to get the seizures down.”

How to have effective consultations on contraception in pharmacy

What benefits do long-acting reversible contraceptives offer compared with other available methods?

Community pharmacists can use this summary of the available devices to address misconceptions & provide effective counselling.

Content supported by Bayer

- 1Antiepileptic drugs: review of safety of use during pregnancy. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2021.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/public-assesment-report-of-antiepileptic-drugs-review-of-safety-of-use-during-pregnancy/antiepileptic-drugs-review-of-safety-of-use-during-pregnancy (accessed 16 Jun 2021).

- 2Ikonomidou C, Turski L. Antiepileptic drugs and brain development. Epilepsy Res 2010;88:11–22. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.09.019

- 3Meador K, Pennell P, May R, et al. Effects of periconceptional folate on cognition in children of women with epilepsy: NEAD study. Neurology 2020;94:e729–40. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000008757

- 4Sadat-Hossieny Z, Robalino C, Pennell P, et al. Folate fortification of food: Insufficient for women with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2021;117:107688. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107688

- 5Perucca P, Anderson A, Jazayeri D, et al. Antiepileptic Drug Teratogenicity and De Novo Genetic Variation Load. Ann Neurol 2020;87:897–906. doi:10.1002/ana.25724

- 6Pennell P, Meador K. Reducing birth defects in women with epilepsy: Research leading to results. Neurology 2019;93:375–6. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000007999

- 7Chen Y, Chiou H, Lin H, et al. Affect of seizures during gestation on pregnancy outcomes in women with epilepsy. Arch Neurol 2009;66:979–84. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2009.142

- 8Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al. Declining malformation rates with changed antiepileptic drug prescribing: An observational study. Neurology 2019;93:e831–40. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000008001

- 9Meador K, Baker G, Browning N, et al. Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure and cognitive outcomes at age 6 years (NEAD study): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:244–52. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70323-X

- 10[MI] Medicines in Pregnancy Registry: Valproate use in females aged 0 to 54 in England (April 2018 to September 2020). NHS Digital. 2021.https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mi-medicines-in-pregnancy-registry/valproate-use-in-females-aged-0-to-54-in-england-april-2018-to-september-2020 (accessed 16 Jun 2021).

- 11Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al. Comparative risk of major congenital malformations with eight different antiepileptic drugs: a prospective cohort study of the EURAP registry. Lancet Neurol 2018;17:530–8. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30107-8

- 12EPILEPSY MEDICINES AND PREGNANCY. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2021.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/950069/Epilepsy-medicines-in-pregnancy-leaflet.pdf (accessed 16 Jun 2021).

- 13Pennell P, French J, May R, et al. Changes in Seizure Frequency and Antiepileptic Therapy during Pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2547–56. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2008663