BRUKINSA is a next-generation Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), accepted by Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) and approved by Health Service Executive (HSE) as a treatment option for adult patients with CLL in treatment-naïve (TN) and relapsed/refractory (R/R) settings — a decision that is supported by robust data from multiple clinical studies[1–7].

CLL is a growing global concern[8–11]

CLL incidence, morbidity and mortality have considerably increased globally from 1990 to 2019 and are projected to rise[8–11].

Since targeted therapies have become available, patient outcomes have improved dramatically, but there are many factors to consider when making a treatment decision[12,13]. Co-morbidities are common in CLL patients because of the natural age distribution of the disease. Genetic features, including unmutated IGHV, mutated TP53 and del(17p), have been associated with worse outcomes, resulting in a need for treatments that are more tolerable and effective for a wider range of patients[12–15].

BRUKINSA is an oral BTK inhibitor that has demonstrated superior progression-free survival (PFS) vs bendamustine-rituximab (BR) in treatment-naïve CLL and vs ibrutinib in R/R CLL. It has shown consistent and durable efficacy across lines of therapy and subgroups, including patients with unmutated IGHV, del(17p) and/or TP53 mutation. It has a demonstrated safety profile across B-cell malignancies for over five years, with no new safety signals reported over time[1–3,16–20].

BRUKINSA: Reimbursed and available…[5–7]

…in England and Wales

Since 22nd November 2023, NICE recommends BRUKINSA for the treatment of patients with:

- Untreated CLL if there is a 17p deletion or TP53 mutation

- Untreated CLL without a 17p deletion or TP53 mutation, and fludarabine-cyclophosphamide-rituximab (FCR) or BR is unsuitable

- R/R CLL

For untreated CLL, BRUKINSA is cost effective compared with usual treatments in high-risk CLL, or for non-high-risk CLL when FCR or BR is unsuitable. For R/R CLL, BRUKINSA is cost effective compared with usual treatments[5].

…in Scotland

BRUKINSA has been accepted for restricted use within NHS Scotland. With the indication under review, BRUKINSA has been recommended as a monotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with CLL. There is a SMC restriction for adults with CLL in whom chemo-immunotherapy is unsuitable[6].

…in Ireland

The HSE has approved BRUKINSA for use and reimbursement in Ireland as monotherapy for adult patients with[7]:

- Previously untreated CLL in the presence of del(17p) or TP53 mutation when they are unsuitable for chemoimmunotherapy

- CLL who have received at least one prior therapy

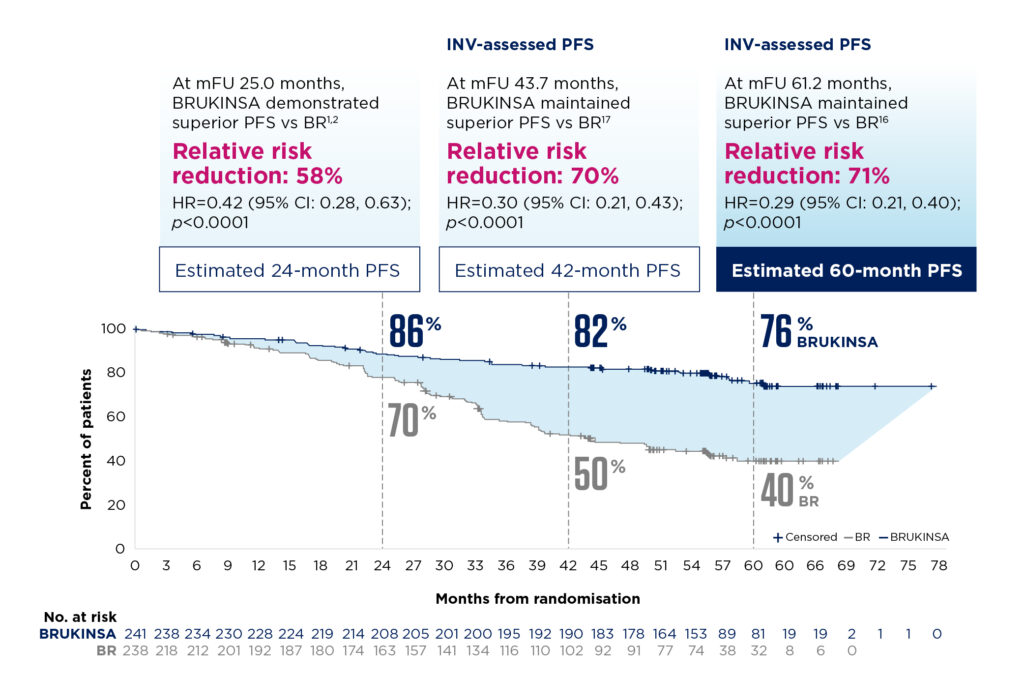

BRUKINSA has demonstrated superior efficacy vs BR over five years in TN CLL[16]

SEQUOIA was a pivotal Phase 3 study of BRUKINSA vs BR in TN CLL[2]

In SEQUOIA, two cohorts were evaluated; Cohort 1 was for patients without del(17p), randomly assigned to BRUKINSA 160 mg BID (n=241) or BR for a maximum of six cycles (n=238). BR was not considered a suitable treatment for patients with del(17p), so this group received BRUKINSA in a single-arm analysis (Cohort 2; n=111)[2].

The primary endpoint was PFS (IRC-assessed) in Cohort 1. Secondary endpoints included overall response rate (ORR), PFS, and overall survival (OS)[2].

More than 75% of patients were alive and progression-free at five years[16]

With extended follow-up, patients without del(17p) treated with BRUKINSA continued to demonstrate a PFS benefit vs BR. At a median follow-up of 61.2 months, median PFS was not reached with BRUKINSA vs 44.1 months with BR. PFS was significantly improved with BRUKINSA vs BR regardless of IGHV mutational status[16].

In Cohort 2 (n=111), survival outcomes for patients with del(17p) were similar to those in Cohort 1; the 24-month PFS rate was 89%[2]. At the extended follow-up of 47.9 months, efficacy was maintained with a 42-month PFS rate of 79%[17].

For patients without del(17p), the investigator-assessed ORR was 98% with BRUKINSA (median follow-up of 61.2 months), including 20.7% achieving a complete response[16].

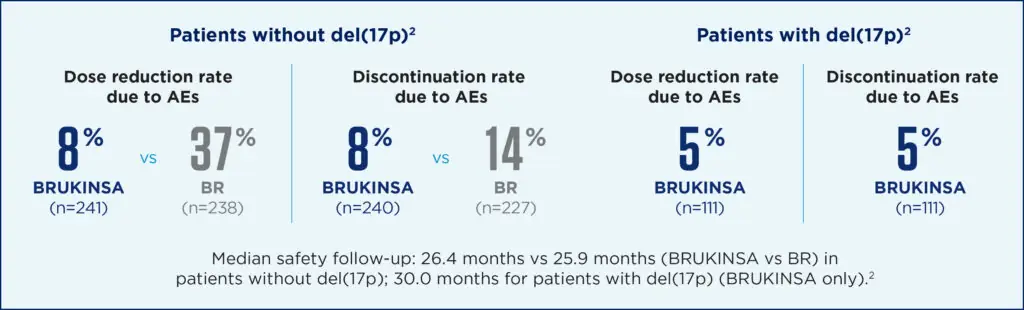

BRUKINSA had a favourable safety profile in both cohorts, including a low incidence of atrial fibrillation and flutter. Additionally, fewer patients discontinued or reduced BRUKINSA due to adverse events (AEs) in both cohorts[2].

For further study information, see BRUKINSA.co.uk (clicking on this link directs you to a promotional website containing information on BRUKINSA).

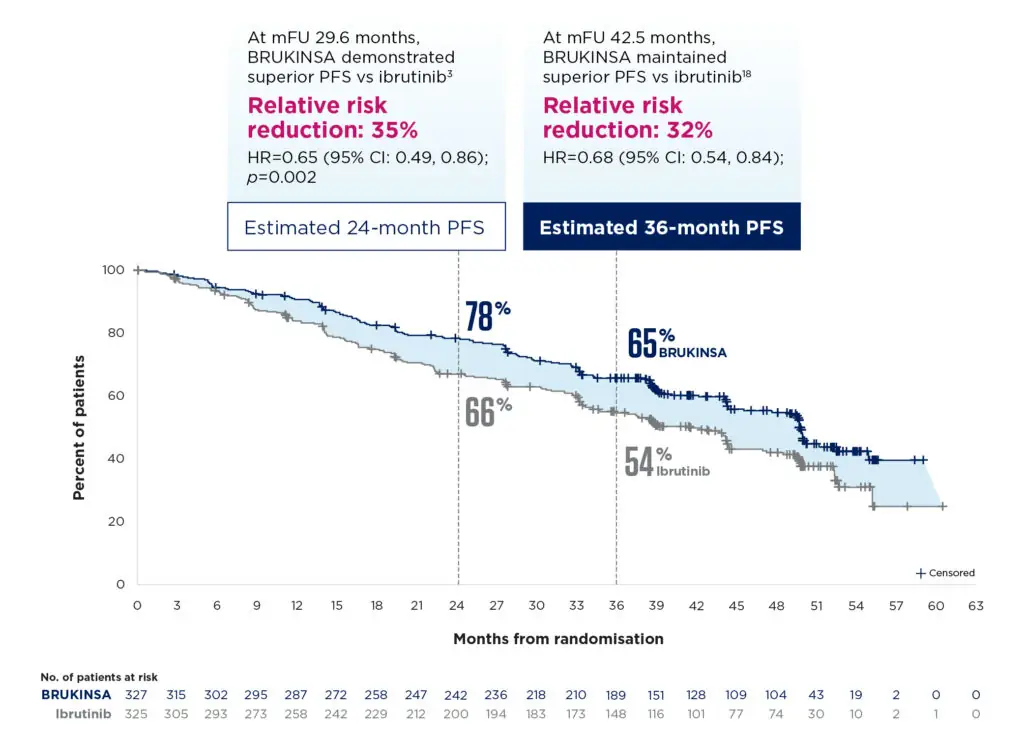

BRUKINSA is the first and only BTK inhibitor to demonstrate superior efficacy vs ibrutinib in R/R CLL[3]

ALPINE was a pivotal Phase 3 study of BRUKINSA vs ibrutinib in R/R CLL[3]

In ALPINE, 652 patients were randomised to receive BRUKINSA 160 mg BID (n=327) or ibrutinib 420 mg QD (n=325). The primary endpoint was ORR (investigator-assessed). Key secondary endpoints included PFS, duration of response (DoR), OS and incidence of atrial fibrillation/flutter[3].

With a median follow-up of 29.6 months, BRUKINSA demonstrated superior ORR vs ibrutinib (80% vs 71% for BRUKINSA vs ibrutinib, respectively, in the intention-to-treat [ITT] population; investigator-assessed; superiority two-sided: p=0.0133)[3].

With extended follow-up, superior clinical benefit was maintained in both ORR and PFS vs ibrutinib. The ORR at 48 months was 90% with BRUKINSA vs 83% with ibrutinib[18].

Key secondary endpoint: Investigator-assessed PFS showed sustained clinical benefit over 3.5 years[18]

Consistent clinical benefit was observed in the subgroup of patients with del(17p) and/or TP53 mutation (n=150). At 29.6 months follow-up, the ORR was 81% with BRUKINSA vs 64% with ibrutinib[3]. At extended follow-up, the 36-month PFS rate was 59.2% with BRUKINSA vs 38.5% with ibrutinib[18].

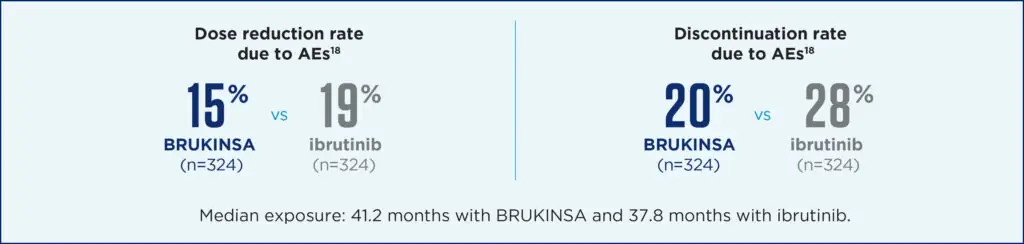

BRUKINSA was well tolerated. Lower rates of cardiac disorders vs ibrutinib were observed, and there were no cardiac deaths in the BRUKINSA arm, whereas 6 patients who received ibrutinib had a fatal cardiac event. Lower rates of atrial fibrillation/flutter were observed with BRUKINSA vs ibrutinib (7% vs 17%, respectively). Fewer patients discontinued or reduced their dose with BRUKINSA due to AEs[18].

For further study information, see BRUKINSA.co.uk (clicking on this link directs you to a promotional website containing information on BRUKINSA).

BRUKINSA’s manageable safety profile is well documented and consistent across indications[1,20]

Safety data have been pooled from ten clinical studies of BRUKINSA monotherapy in 1,550 patients with B-cell malignancies. Exposure-adjusted incidence rates showed that AEs of interest remained stable or decreased over time on BRUKINSA treatment[1,20].

At a median exposure duration of 34.41 months, 4.8% of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse reactions. The most frequent adverse reaction leading to treatment discontinuation was pneumonia (2.6%). Adverse reactions leading to a dose reduction occurred in 5.0% of patients[1]. Refer to the BRUKINSA SmPC for complete safety information.

Unmatched dosing flexibility among BTK inhibitors[1,21,22]

BRUKINSA is an oral therapy that is taken daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Treatment with BRUKINSA offers once-daily or twice-daily dosing options.

BRUKINSA can be co-administered with protein-pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) without compromising efficacy and can be dose adjusted for patients who are taking moderate and strong CYP3A inhibitors.

BRUKINSA is the only covalent BTKi with a recommended dose for patients with severe hepatic impairment (80mg twice daily)[1,21,22].

Refer to the BRUKINSA SmPC for complete information before initiating therapy with BRUKINSA.

Find out more about BRUKINSA for the treatment of your patients with CLL

BRUKINSA (zanubrutinib) as monotherapy is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with[1]:

- CLL

- Waldenström’s macroglobulinaemia (WM) who have received at least one prior therapy, or in first-line treatment for patients unsuitable for chemo-immunotherapy

- Marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) who have received at least one prior anti-CD20-based therapy

- Mantle cell lymphoma who have received at least one prior therapy

Click here for BRUKINSA prescribing information

▼ This medicine is subject to additional monitoring. This will allow quick identification of new safety information. Report any suspected adverse reactions.

Adverse events should be reported. United Kingdom: Healthcare professionals are asked to report any suspected adverse reactions via the Yellow Card Scheme found at www.mhra.gov.uk/yellowcard. Adverse events should also be reported to BeOne Medicines at adverse_events@beonemed.com

Abbreviations

AE, adverse event; BID, twice daily; BR, bendamustine-rituximab; BTK, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase; CI, confidence interval; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CR, complete response; CYP3A, Cytochrome P450, family 3, subfamily A; del(17p), deletion of the short arm of chromosome 17; DoR, duration of response; FCR, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab; H2RA, histamine H2-receptor antagonist; HR, hazard ratio; HSE, Health Service Executive; IGHV, immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region genes; IRC, independent review committee; ITT, intention-to-treat; mPFS, median progression-free survival; MZL, marginal zone lymphoma; NE, non-evaluable; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PPI, proton-pump inhibitor; PR, partial response; QD, once daily; R/R, refractory/relapsed; SMC, Scottish Medicines Consortium; SmPC, Summary of Product Characteristics; TN, treatment-naive; TP53, tumour protein P53; WM, Waldenström’s macroglobulinaemia.

0625-BRU-PRC-023 | October 2025

- 2Tam CS, Brown JR, Kahl BS, et al. Zanubrutinib versus bendamustine and rituximab in untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SEQUOIA): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2022;23:1031–43.

- 3Brown JR, Eichhorst B, Hillmen P, et al. Zanubrutinib or Ibrutinib in Relapsed or Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:319–32.

- 4Tam CS, Muñoz JL, Seymour JF, et al. Zanubrutinib: past, present, and future. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13.

- 5TA931. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA931 (accessed October 2025)

- 6SMC2600. Scottish Medicines Consortium. 2023. https://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/medicines-advice/zanubrutinib-brukinsa-abbreviated-smc2600 (accessed October 2025)

- 7Cancer Drugs Approved for Reimbursement: Zanubrutinib. Health Service Executive. 2023. https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/5/cancer/profinfo/medonc/cdmp/new.html (accessed October 2025)

- 8Yao Y, Lin X, Li F, et al. The global burden and attributable risk factors of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: analysis based on the global burden of disease study 2019. BioMed Eng OnLine. 2022;21.

- 9van der Straten L, Maas CCHM, Levin M-D, et al. Long-term trends in the loss in expectation of life after a diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a population-based study in the Netherlands, 1989–2018. Blood Cancer J. 2022;12.

- 10Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. 2023. https://www.lls.org/sites/default/files/file_assets/PS34_CLL_Booklet_2019_FINAL.pdf (accessed October 2025)

- 11Ou Y, Long Y, Ji L, et al. Trends in Disease Burden of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia at the Global, Regional, and National Levels From 1990 to 2019, and Projections Until 2030: A Population-Based Epidemiologic Study. Front. Oncol. 2022;12.

- 12Bennett R, Seymour JF. Update on the management of relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2024;14.

- 13Walewska R, Parry‐Jones N, Eyre TA, et al. Guideline for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2022;197:544–57.

- 14Patel K, Pagel JM. Current and future treatment strategies in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14.

- 15Estupiñán HY, Berglöf A, Zain R, et al. Comparative Analysis of BTK Inhibitors and Mechanisms Underlying Adverse Effects. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;9.

- 16Shadman M, Munir T, Robak T, et al. Zanubrutinib Versus Bendamustine and Rituximab in Patients With Treatment-Naïve Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma: Median 5-Year Follow-Up of SEQUOIA. JCO. 2025;43:780–7.

- 17Shadman M, Munir T, Robak T, et al. Zanubrutinib vs Bendamustine + Rituximab in Patients With Treatment-Naive Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma: Extended Follow-Up of the SEQUOIA Study. International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma, June 13–17, 2023. Abstract 154. 2023. 2023. https://www.beonemedinfo.com/CongressDocuments/Shadman_BGB-3111-304_ICML_Presentation_2023.pdf (accessed October 2025)

- 18Brown JR, Eichhorst B, Lamanna N, et al. Sustained benefit of zanubrutinib vs ibrutinib in patients with R/R CLL/SLL: final comparative analysis of ALPINE. Blood. 2024;144:2706–17.

- 19D’Sa S, Dimopoulos M, Juczak W, et al. Long-Term Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Waldenström Macroglobulinemia Who Received Zanubrutinib in the Phase 3 ASPEN Study: A Report From the Zanubrutinib Extension Study. ASH Annual Meeting, December 7–10, 2024. Abstract 3031. 2024. https://www.beonemedinfo.com/CongressDocuments/DSa_BGB-3111-LTE1_ASH_Poster_2024.pdf (accessed October 2025)

- 20Brown JR, Ghia P, Jurczak W, et al. Characterization of zanubrutinib safety and tolerability profile and comparison with ibrutinib safety profile in patients with B-cell malignancies: post hoc analysis of a large clinical trial safety database. haematol. 2024.

BRUKINSA and BeOne Medicines are trademarks owned by BeOne Medicines I GmbH or its affiliates. © BeOne Medicines I GmbH, 2025 All Rights Reserved.