Shutterstock.com

Eczema — also known as atopic dermatitis — is characterised by relapsing episodes of skin inflammation and intense itching, resulting in a rash and dry skin lesions that can bleed, ooze and become infected. Eczema has two main pathological elements: impaired skin barrier function and immune dysfunction.

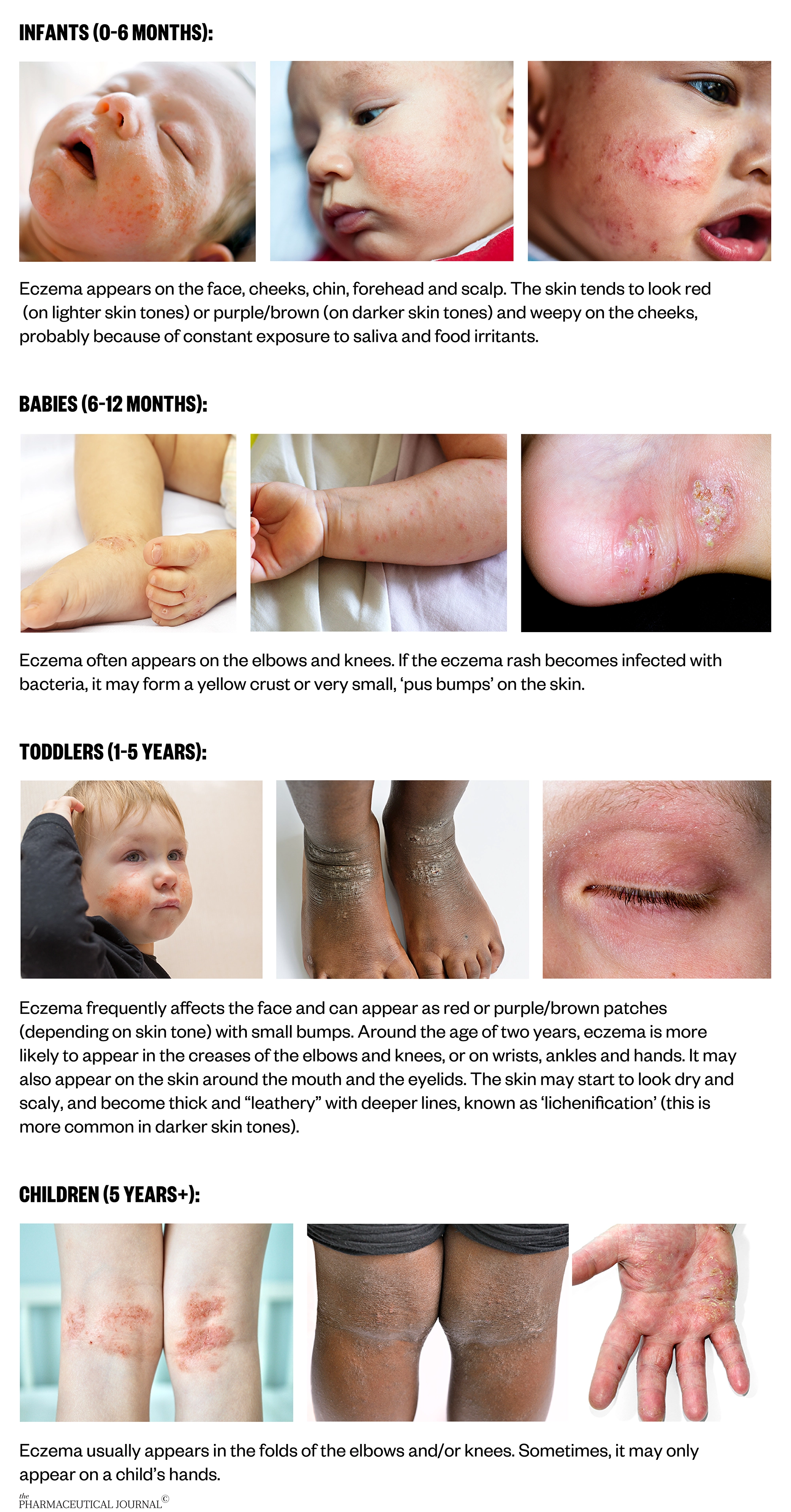

The appearance and location of eczema changes as children grow and looks different on different skin tones.

Photos: Source: Jacek Sopotnicki / Alamy Stock Photo; Engdao Wichitpunya / Alamy Stock Photo; Zenobillis / Alamy Stock Photo; Dr P Marazzi / Science Photo Library; Shutterstock.com; National Eczema Association

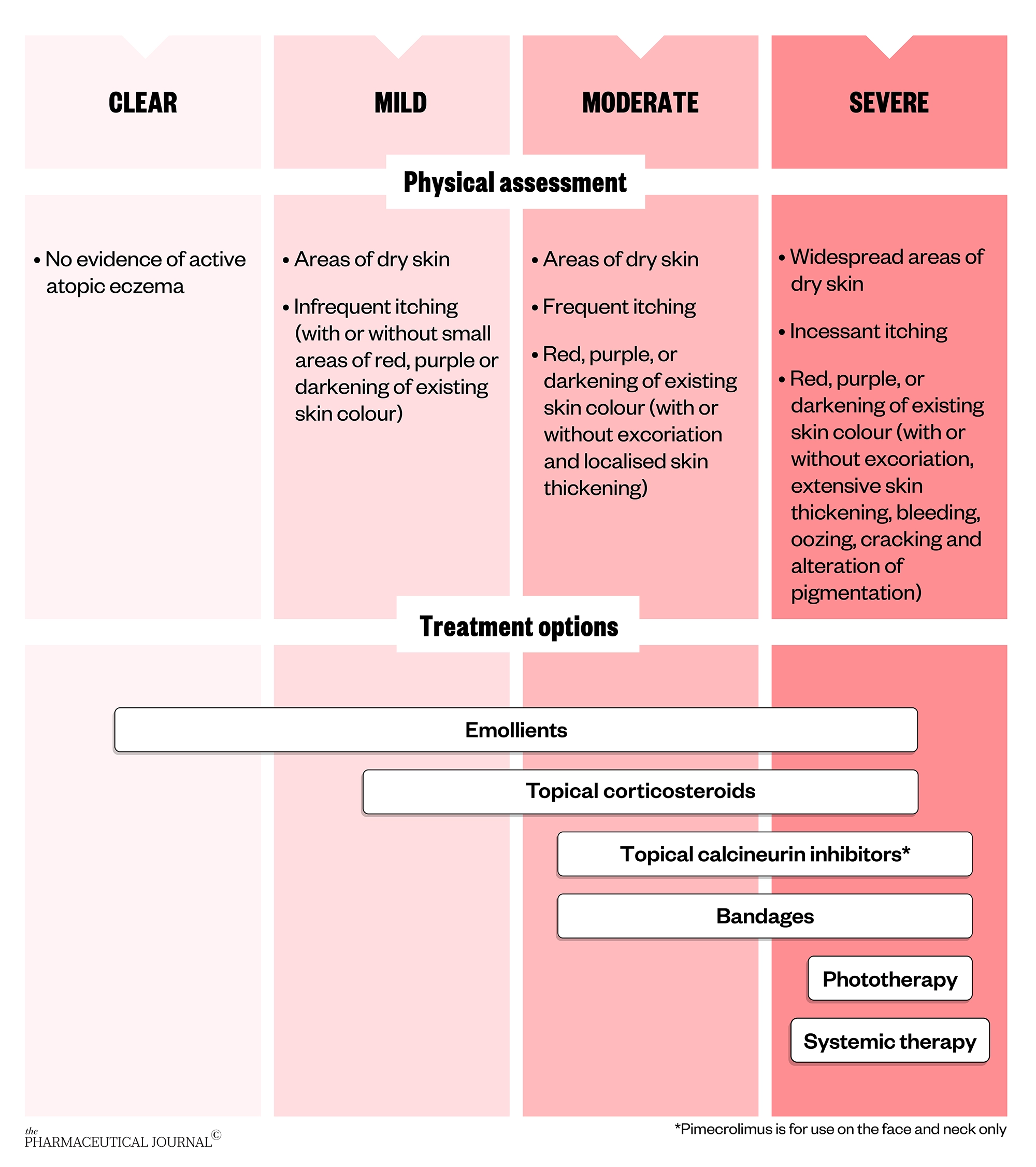

Treatment pathway

Eczema management should take a stepped approach, where treatment is tailored to the severity of the disease.

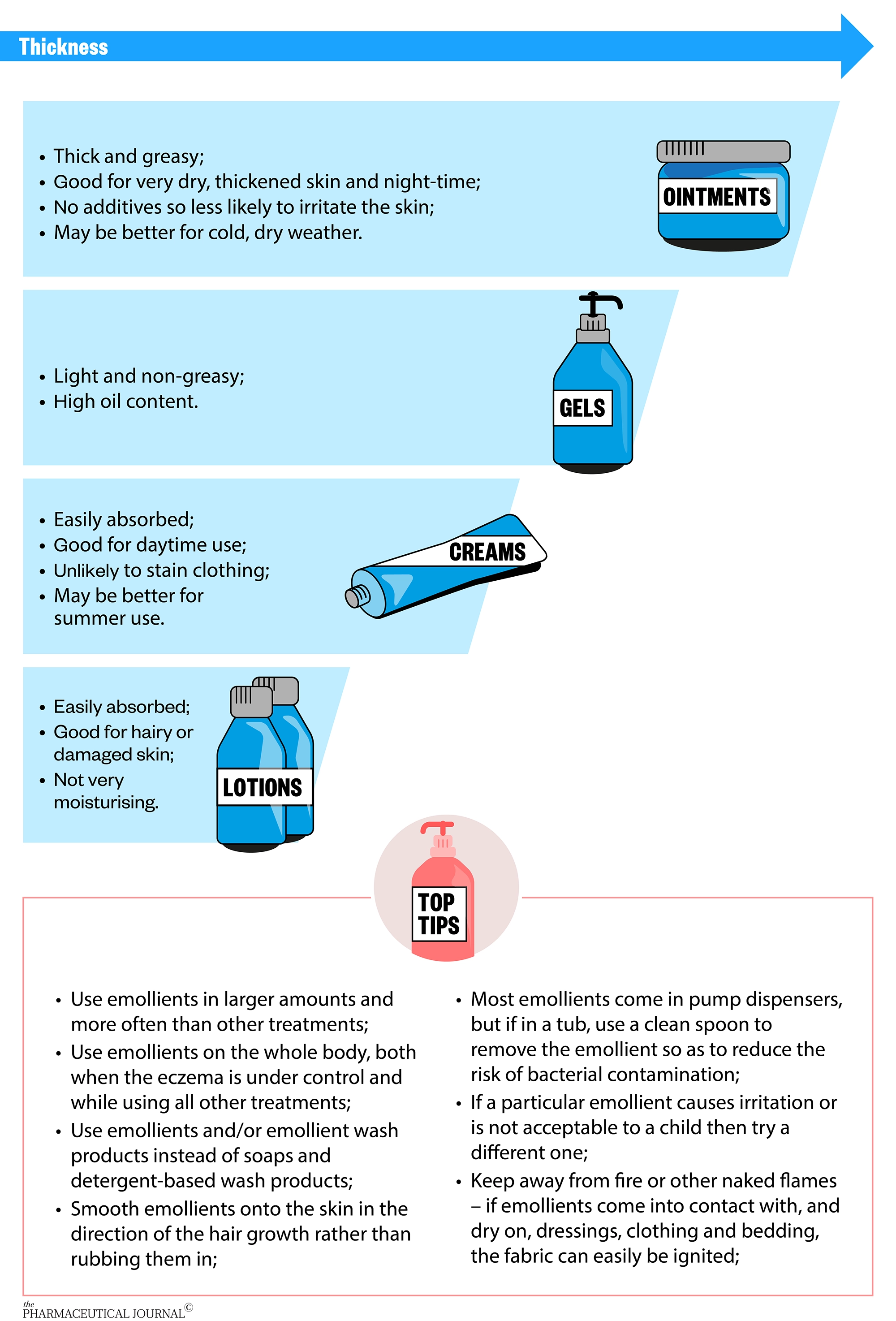

Correct use of emollients

Emollients target impaired skin barrier function and form part of eczema management by hydrating the skin. They are especially useful when eczema is under control in order to prevent flares. Emollients may increase the efficacy of topical corticosteroids (TCS) and should continue to be used throughout treatment.

There are many different emollients available but little evidence to recommend a particular type. A 2017 Cochrane review, which identified 77 trials, concluded that most emollients appear to be effective but was unable to find reliable evidence that one is better than another.

The ‘Best emollients for eczema’ study, a randomised controlled trial to compare the effectiveness and acceptability of four types of emollient (lotion, cream, gel and ointment), is due to report later in 2021.

In the meantime, a choice of emollients should be offered based on the child’s needs and preferences. For example, lighter and less greasy emollients are often chosen for the face to avoid a shiny look that might be unacceptable to teenagers. Thicker emollients might be preferred in colder dry weather, whereas lighter emollients may be preferred in warmer summer weather.

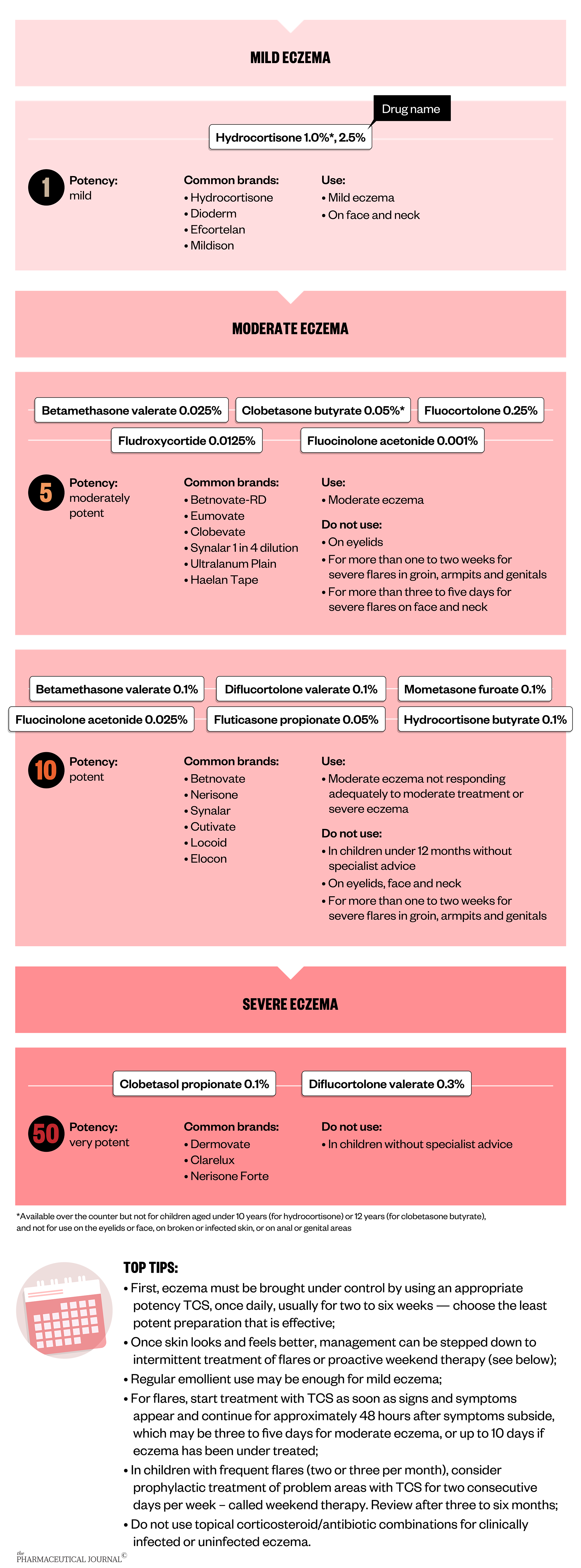

Tackling concerns about topical corticosteroids

TCS target the underlying skin inflammation that may result from immune and skin barrier dysfunction and are essential to treat and prevent eczema flares. Despite TCS being a mainstay of treatment for eczema for more than 50 years, many parents, carers and healthcare professionals have concerns about using them in children.

A study involving 105 community pharmacists, based in Berkshire, UK, showed they were less likely to provide patient counselling on the safety of TCS than on their indication, application and formulation, possibly owing to their own lack of knowledge in this area. More than 50% of the pharmacists incorrectly believed that side effects, such as skin thinning, are common even when TCS are used appropriately (see Box).

Box: Skin thinning and other adverse effects with topical corticosteroids

Local adverse effects of topical corticosteroids (TCS) can include:

- Transient burning or stinging;

- Worsening and spreading of misdiagnosed fungal infection;

- Reversible thinning of the skin;

- Stretch marks;

- Allergic contact dermatitis;

- Acne vulgaris;

- Reversible, mild hypopigmentation;

- Excessive hair growth at the site of application.

Some thinning of the skin is a desirable therapeutic effect of TCS, restoring abnormally thick chronic eczema to normal skin thickness. However, parents are often concerned about abnormal skin thinning with TCS use, making the blood vessels more visible and the skin more likely to bruise or tear. In a survey of 200 dermatology outpatients, 72.5% of people worried about using TCS on their own or their child’s skin, with the perceived risk of skin thinning (34.5%) the most frequent cause for concern.

However, a recent review bringing together all safety data from 38 systematic reviews of TCS use in adults and children with eczema, found that skin thinning is uncommon when TCS are used intermittently ‘as required’ to treat flares or on two days a week as ‘proactive weekend therapy’ to prevent flares.

Although most data were from short-term studies, one study showed there was only one episode of skin thinning in 1,213 children using mild/moderate TCS as required with five-year follow-up. And trials using TCS as proactive weekend therapy generally included 16–20 weeks of follow-up.

The risks of skin thinning with TCS are increased with:

- Using potent or very potent TCS;

- Inappropriate long-term continuous use;

- Treating sensitive sites where the skin is thinner, e.g. face or genital areas;

- Using TCS under occlusion, e.g. a nappy, dressing, or when applying in skin folds;

- Treating large areas.

Children, especially infants, are particularly susceptible to systemic adverse effects of TCS because they have a proportionately greater body surface area to weight ratio, and so there is a greater degree of absorption for the same amount applied. However, systemic effects, which include adrenal suppression, Cushing’s syndrome and growth suppression, are rare.

The potency of TCS to use is chosen depending on the age of the patient, the severity of the eczema and the part of the body on which they are being used. The percentage concentration of the TCS does not relate to its potency and it is important that patients know which potency to use where.

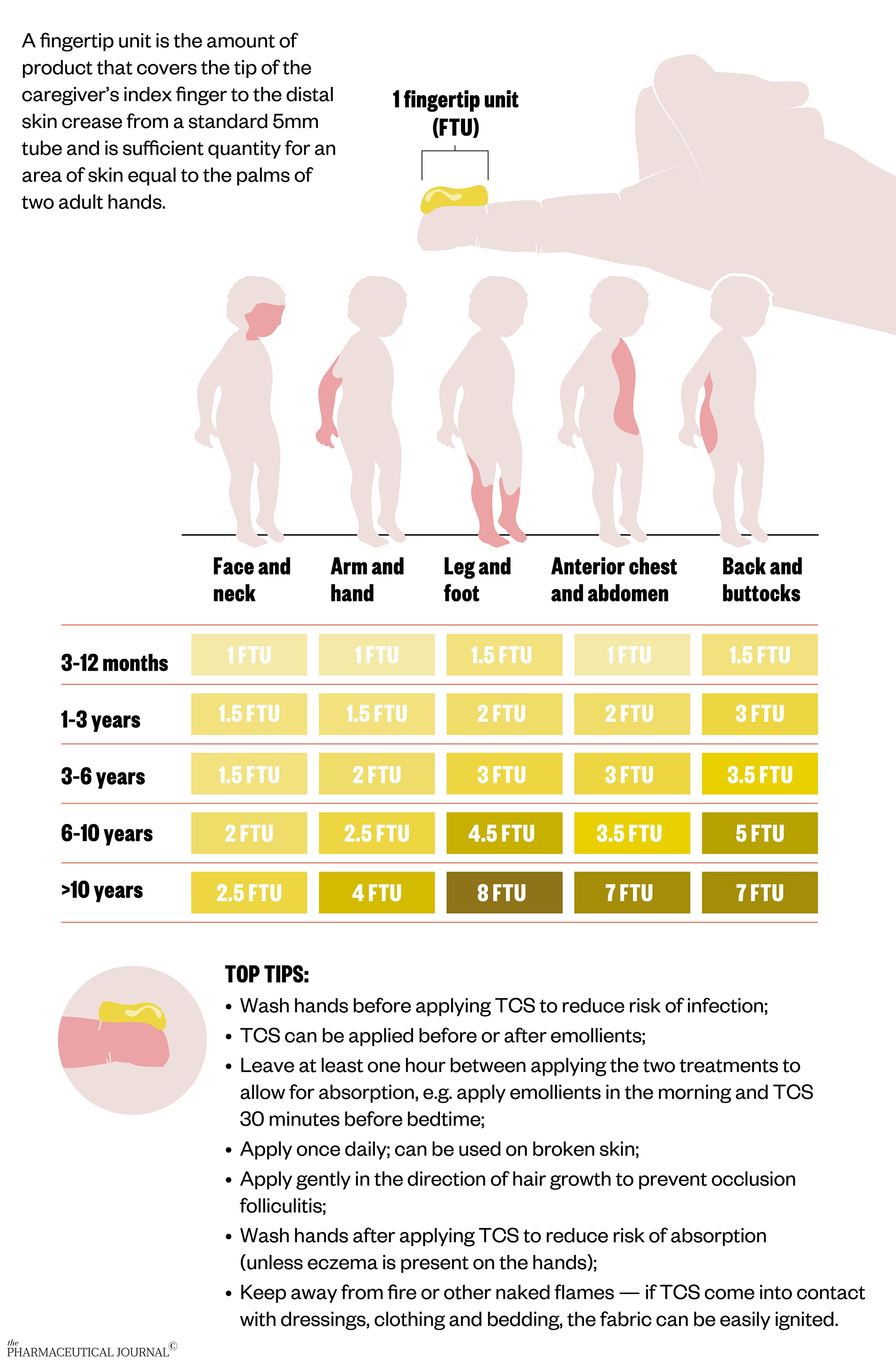

Advice to apply TCS sparingly is not appropriate for use in eczema and can lead to confusion and anxiety. Parents and carers can use fingertip units as a guide to how much TCS to apply for each part of the body.

When to re-consult

In the following situations, parents and carers should continue to use TCS but make an appointment to see their child’s GP:

- If eczema is not clearing after seven days of using a TCS despite adequate use (ask to see the tubes of creams/ointments for evidence);

- If the child’s skin develops clusters of itchy and painful blisters, often on the face and neck, or is unwell with a fever and swollen local lymph nodes (signs of eczema herpeticum), this requires a same-day appointment;

- If eczema on the face has not responded to appropriate treatment;

- If the child is suffering psychological upset or sleep problems despite regular treatment.

Some parents or carers may have concerns about topical steroid withdrawal. More information can be found on this from the National Eczema Society.

Editorial advisers: Hywel Williams, professor of dermato-epidemiology and co-director, Centre of Evidence-Based Dermatology, University of Nottingham and Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust; Jane Harvey, pharmacist and research assistant, Centre of Evidence-Based Dermatology, University of Nottingham; Matthew Ridd, a GP in Portishead, Somerset, and reader at the Centre for Academic Primary Care, University of Bristol; Stephanie Lax, research assistant, Centre of Evidence-Based Dermatology, University of Nottingham; Kim Thomas, professor of applied dermatology research and co-director of the Centre of Evidence-Based Dermatology, University of Nottingham; Laura Howells, research fellow, Centre of Evidence-Based Dermatology, University of Nottingham; Miriam Santer, professor of primary care research within medicine at the University of Southampton and a GP at Denmark Road Medical Centre in Bournemouth; and Ingrid Muller, health psychologist and lecturer in the School of Primary Care, Population Sciences and Medical Education.