Science Photo Library

After reading this learning article, you should be able to:

- Understand the causes of the different types of epidermolysis bullosa (EB);

- Identify the symptoms of EB and know how the disease is diagnosed;

- Understand the management of EB, with particular focus on wound and pain management.

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a genetic skin condition[1–4]. It encompasses several disorders characterised by recurrent blister formation that result from structural fragility within the skin and other selected tissues[4]. EB is classified by the level of tissue separation within the cutaneous basement membrane zone of the skin[5]. One in 227 individuals carry a defective gene that causes EB and one in 17,000 live births experience a form of EB[4]. There are around 5,000 people in the UK living with EB, with males and females being equally affected[2,4]. Certain types of EB can be fatal and others are severely life-limiting[2].

Painful open wounds and sores form when damage occurs to this exceptionally fragile skin; an example can be seen in Figure 1[4]. In some cases, internal linings (e.g. in the mouth and stomach) and organs are also affected[6]. Complications from secondary infection and extensive scarring often affect people living with EB[2].

Science Photo Library

Optimal management requires a multidisciplinary approach that focuses on the protection of susceptible tissues against trauma; use of sophisticated wound care dressings; aggressive nutritional support; and early medical or surgical interventions to correct extracutaneous complications, whenever possible[7]. It is important that pharmacists are aware of the symptoms and management of EB, as they may need to assist in providing complex tailored treatment as part of the multidisciplinary team. Prognosis varies considerably and is based on the EB subtype and overall health of the patient.

Causes

EB is a genetically inherited condition and may be inherited in either a dominant or recessive manner[2]. In dominant EB, one parent usually carries the gene and is affected by the condition[2]. EB may also arise through a new spontaneous mutation[2]. In rare cases, a severe form of EB can be “acquired” owing to autoimmune disease, where the body develops antibodies to attack its own tissue proteins[2].

Types and symptoms

There are five main types of EB. Patients are generally classified and sub-classified based on: ultrastructural level of blister development within the skin; mode of inheritance; and combinations of clinical, electron microscopic immunohistochemical and genotypic features[2].

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex

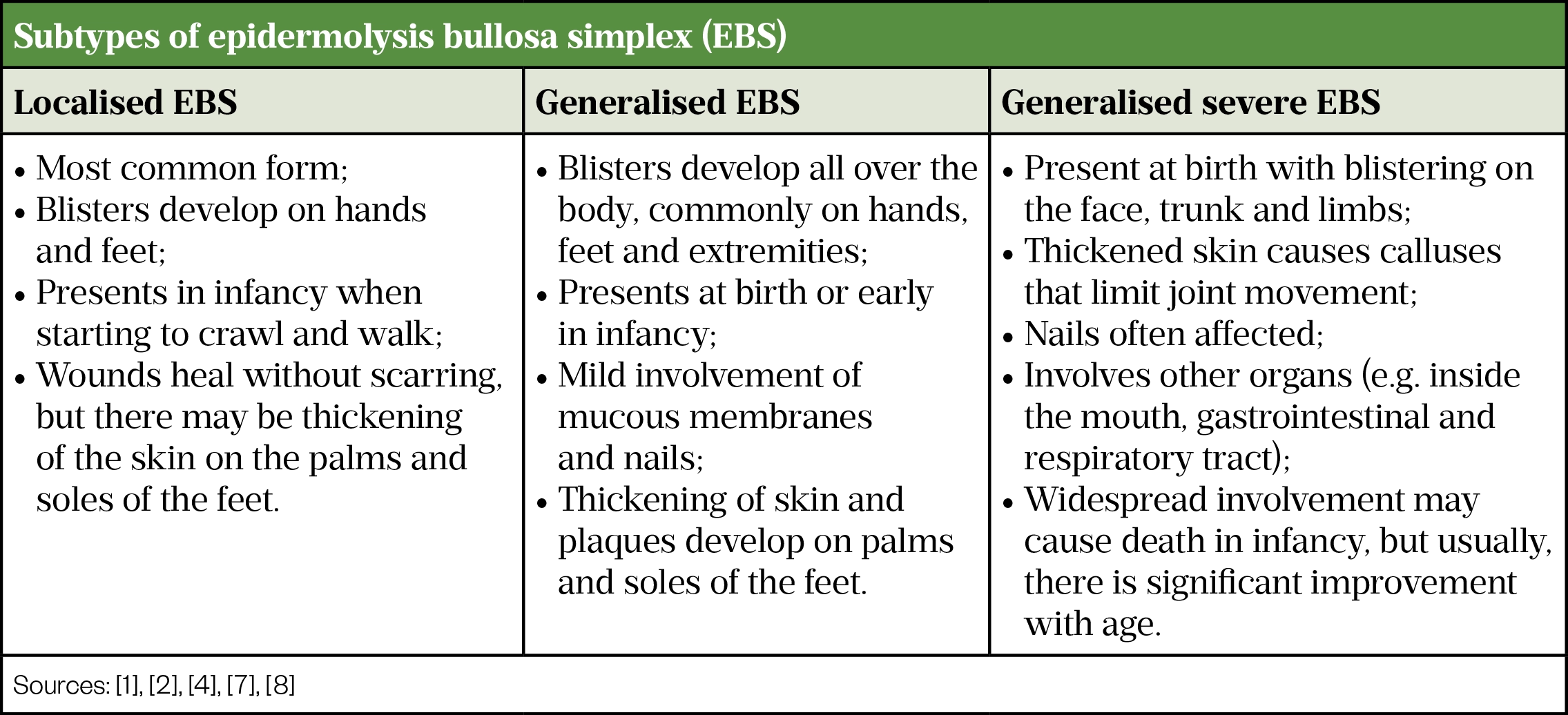

The most common form is EB simplex (EBS), which accounts for around 70% of patients with EB[2]. It is caused by defective proteins that would usually help bind the upper layers of the skin together[2]. EBS is generally dominantly inherited[7] and onset of disease activity is usually at or shortly after birth, although patients with localised EBS may not develop blistering until late childhood or even early adulthood[7].

EBS is usually mild to moderate in severity[2]. Localised intraoral erosions or blisters, which tend to be asymptomatic, occur in around one-third of patients[7]. These are the only common extracutaneous finding in localised EBS usually seen during infancy[7].

There are a range of EBS subtypes (see Table 1) [1,2,4,7,8].

Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa

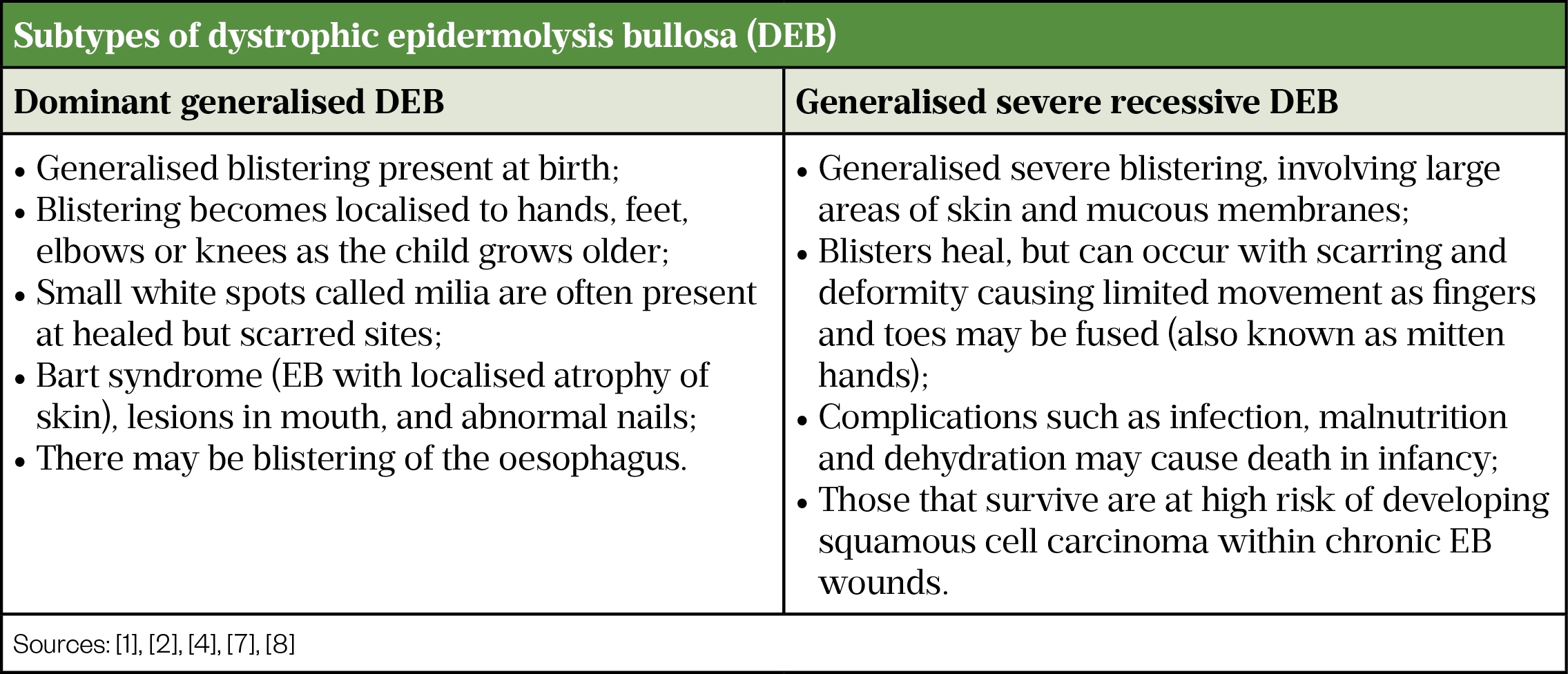

Around 20% of people with EB have dystrophic EB (DEB)[2]. DEB can be moderate or severe depending on the subtype. It affects the dermis, which is where the blistering occurs and may be dominantly or recessively inherited[2].

DEB derives its name from the tendency of the blisters to heal with scarring, leading to:

- Contraction of the joints;

- Fusion of the fingers and toes;

- Contraction of oral membranes;

- Narrowing of the oesophagus[2].

There are two subtypes of DEB (see Table 2) [1,2,4,7,8].

Junctional epidermolysis bullosa

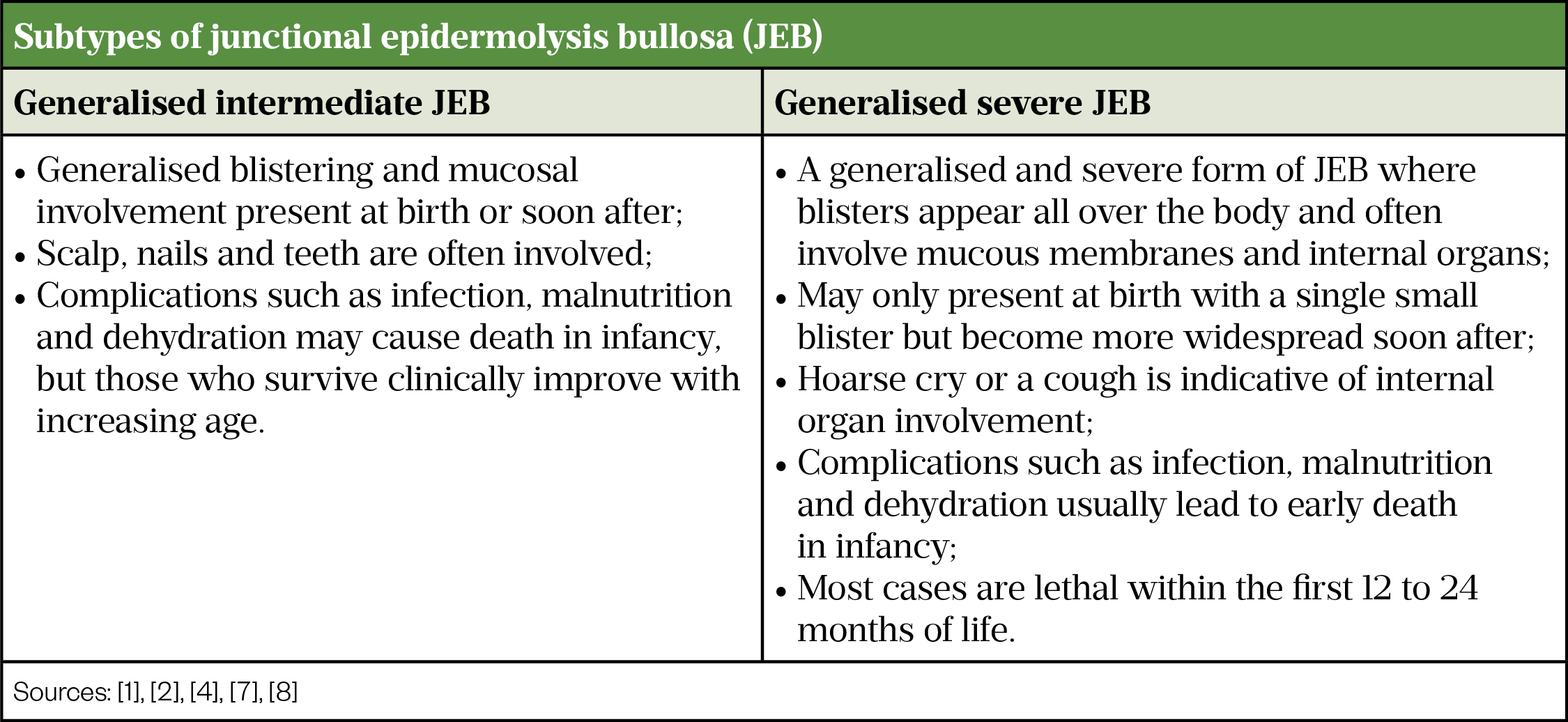

A moderate-to-severe form, junctional EB (JEB) affects the basement membrane, the structure that keeps the epidermis and dermis layers together. The skin easily breaks apart, causing blistering[2]. It is a recessively inherited condition[2] and affects around 10% of people living with EB [2]. Table 3 shows the two subtypes of JEB[1,2,4,7,8].

Kindler syndrome

The rarest type of inherited EB, Kindler syndrome, is recessively inherited[2]. Since it was first identified in 1954, more than 250 cases have been described[9]. Symptoms may include increased sensitivity to light; patchy/discoloured skin; and/or hardening of the skin on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet (hyperkeratosis)[7]. Sometimes the gums and teeth are affected as individuals get older[2,7].

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

The incidence of EB acquisita (EBA) is not well understood owing to it being the rarest type of EB[2,10]. EBA is not inherited and is classified as an autoimmune disease, whereby the body attacks its own healthy tissue[2]. It is thought that immune proteins mistakenly attack healthy collagen — the protein that binds the skin together[2]. Symptoms are usually mild to moderate; blistering tends to mostly affect the hands, knees, knuckles, elbows and ankles[2].

Diagnosis

EB’s rarity means that it is recommended to consult specialised centres at all stages of diagnosis and care. Individuals with a history of recurrent blistering or erosions following mild trauma without other plausible aetiology (e.g. infection) should be suspected of having EB, especially if there is a family history[3]. It is necessary to perform genetic testing for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment[2]. Diagnosis also means that genetic counselling can be provided to the family. Those known to be at risk of passing on EB can receive antenatal diagnostic testing 8–10 weeks into pregnancy[3].

Clinical suspicion of EB is based on chronic recurrent blistering, after exclusion of other causes such as infections[7].

Diagnostic tests include skin biopsies of newly induced blisters, which undergo immunofluorescence antigen mapping and transmission electron microscopy[8]. Indirect immunofluorescence (which reveals low titre circulating IgG autoantibodies that target the basement membranes) is a diagnostic procedure that enables rapid determination of EB type and subtypes, such as for EBA[8].

Management

A patient-centred multidisciplinary approach is required for EB management, as the condition and medical needs vary in each patient. Currently there is no definitive treatment. For all patients, the principles of care to improve quality of life and minimise complications include avoiding trauma; good skin care; infection prevention; and symptom management[11].

Skin care and wound management

Blisters in EB are not self-limiting and will extend rapidly if left unattended[11,12]. They can develop anywhere and may involve mucous membranes[12]. Intact blisters should be lanced at their lowest point and drained to limit tissue damage[11].

The underlying principle of skin and wound management is to select an atraumatic dressing to:

- Prevent blistering and skin damage;

- Minimise pain and bleeding during dressing changes;

- Prevent infection;

- Allow cooling of the blister sites;

- Encourage wound healing[11].

Non-adherent dressings should be used to prevent further skin damage on removal, and secured with appropriate retaining dressings to avoid skin tear and blistering through friction. Silicone medical adhesive removers can be used to remove adherent dressings or clothing to avoid skin damage[11].

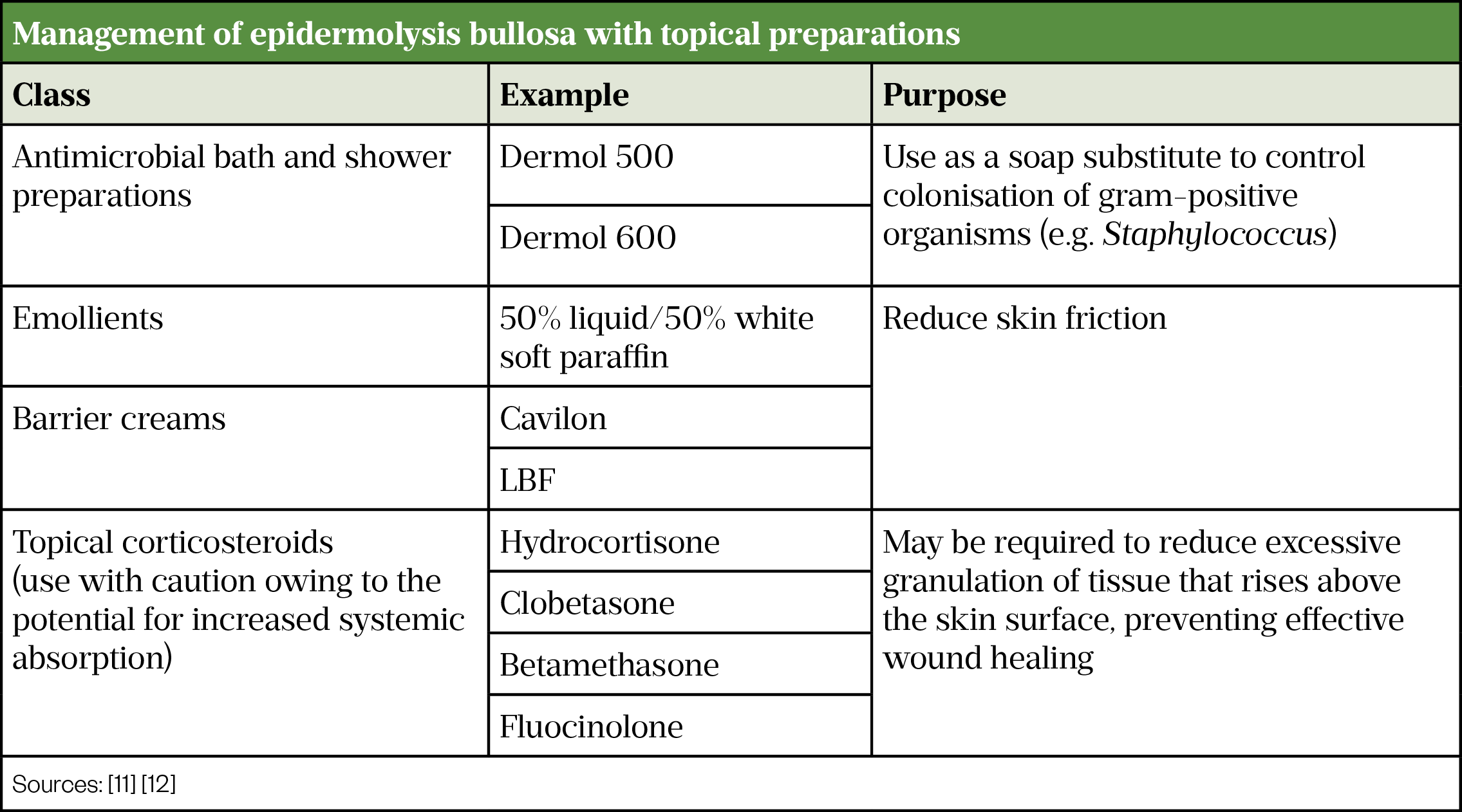

The increased bioburden (i.e. normal flora of human skin) in critically colonised or infected wounds impairs healing[11]. Regular cleaning of chronic wounds is required to reduce infection risk, prevent odour and promote wound healing (see Table 4)[11,12]. Antimicrobial bath and shower preparations can be used as a soap substitute to control colonisation of gram-positive organisms[12]. Emollients and barrier creams should be used to reduce skin friction[11]. Potent topical steroids should be used with caution owing to potential systemic absorption, but may be required in over-granulating wounds (i.e. where an excess of granulation tissue rises above the surface of the wound, hindering healing)[13].

Pain management

Pain is a common complaint with all types of EB and can originate from blister sites, areas of skin loss and affected areas of the mucous membrane[5]. Normal daily routines can involve several painful events; for example bathing, mobilising and dressing changes. EB patients experience complex pain, displaying features of nociceptive (somatic/visceral) pain as well as neuropathic pain[12]. Persistent wound development and poor healing, with recurrent infections, often aggravates the intensity of pain. A patient’s experience of pain is subjective, and strategies to manage pain must engage with patients and their carers to design an individual and dynamic plan that address their needs.

Birch bark extract

NICE issued highly specialised technology guidance in September 2023, recommending birch bark extract within its marketing authorisation as an option for treating partial thickness wounds associated with dystrophic and junctional EB in patients aged 6 months and over. A clinical trial showed that birch bark led to quicker wound healing than a control gel and results suggest that it led to a reduced amount of affected skin[14].

Non-pharmaceutical interventions

Psychological therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), hypnosis and relaxation training may modify pain intensity, reduce related distress, decrease pain-related functional disability and improve pain coping[15]. Distraction, hypnosis and relaxation can be helpful for acute pain, while CBT may benefit those with longstanding pain and pruritus[15].

Complementary and alternative medicine practices (e.g. acupuncture, meditation and music therapy) may have a role in EB[15]. Patients who wish to use homeopathic remedies should be encouraged to consult with pharmacists prior to treatment as some herbal medicines (e.g. birch bark and St John’s wort) may increase risk of bleeding and may not be suitable for patients having surgery or with open wounds[16]. Drug–drug interactions should be considered when herbal medicines are co-administered with other medicines (e.g. St John’s wort with anaesthetic agents via the hepatic cytochrome P450 CYP3A4 isoform)[17].

Pharmaceutical interventions

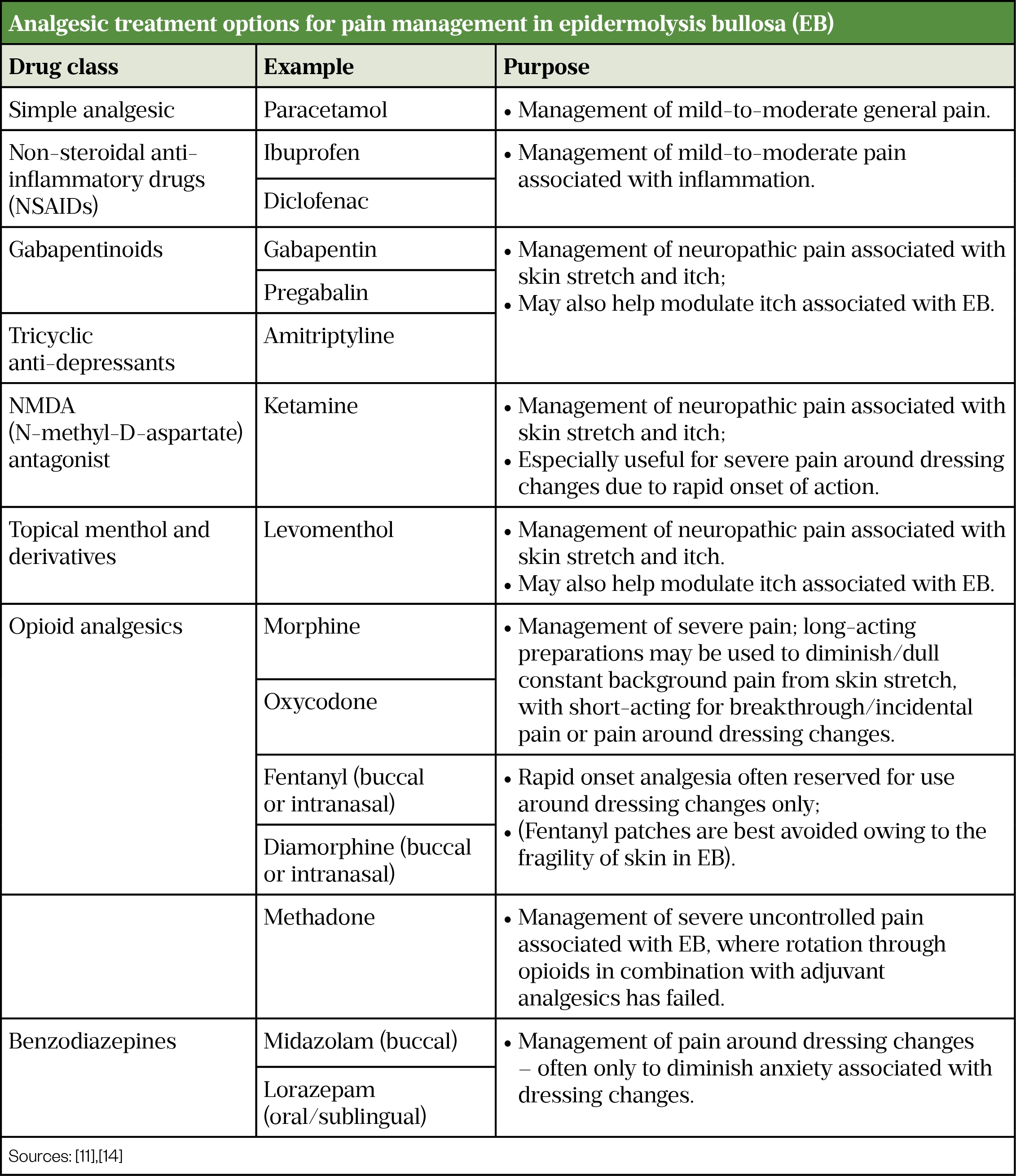

Bathing and dressing changes are the greatest challenges in controlling pain and can be sources of anxiety for patients with EB[15]. Simple analgesics such as paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be effective at managing pain, combined with use of adjuvant analgesics (e.g. gabapentinoids or ketamine) alongside oral opioids[18–21].

Anxiolytics, such as short-acting benzodiazepines (e.g. midazolam), can be considered for acute anxiety prior to dressing changes[15]. Care should be taken when using benzodiazepines with opioids to avoid over-sedation[15]. Table 5 shows the available analgesic treatment options for pain management.

Pruritus

Pruritus can be constant, intense and agonising for patients, and cause significant impairment of quality of life[12]. Healing wounds are particularly pruritic and intense itch provokes scratching that can lead to further damage[11]. Pruritus is part of the pain spectrum and can lead to insomnia and depression[11].

Topical emollients, including moisturisers and bath oils, form an integral part of skin care, by preventing skin dryness and aiding recovery[12,15]. Moisturisers containing sodium lauryl sulphate should be avoided as this can exacerbate skin damage[12]. Antimicrobial moisturisers and menthol-containing topical preparations can reduce itch, while patients with acute severe itch may respond to topical steroids[12]. Non-sedating antihistamines (e.g. cetirizine and loratadine) may be helpful to allow for daytime activities. Adjuvant sedating antihistamines (such as alimemazine, chlorphenamine and hydroxyzine) may be valuable at night to promote rest when the urge to scratch is heightened[12,13]. Other medications that have been used to treat severe recalcitrant itch include gabapentinoids; amitriptyline; ondansetron; thalidomide; aprepitant; and ciclosporin[12,22].

Surgical procedures

Flexion contractures (i.e. bent or flexed joints that cannot be straightened actively or passively) and fusion of the hands and feet (i.e. mitten hands) can develop, owing to recurrent scarring causing permanent disfigurement and disability[23]. Surgical interventions to release contractures of the limbs, repair mitten glove deformity and remove mucosal overgrowth by oesophageal dilatation to preserve airways may be required[11]. Good skin care and oral hygiene and physiotherapy may delay the need for surgery[11]. Many patients may already take regular analgesia; this should be considered when planning peri- and post-operative pain management.

Nutrition

Malnutrition is common, owing to swallowing difficulties caused by blistering of the oral mucosa[11]. Reduced food intake and increased metabolic demands from wound healing lead to failure to thrive, delayed puberty and anaemia, which may further affect wound healing and skin integrity[12]. Early input from dietitians, encouraging a hypercaloric diet, is essential[12]. Supplementary nutrition via a percutaneous gastric tube is sometimes required[11]. Correction of anaemia, using oral and intravenous iron supplements, is needed for patients with venous ulcers to avoid impaired wound healing[12]. Medication-induced constipation can lead to reluctance to eat, and can be addressed with adequate hydration, increased fibre intake and stool softeners[15].

Head lice

Infestations of head lice are common among schoolchildren and management can be difficult in children with EB. If infestation is not controlled quickly, scratching of the scalp will lead to infection, permanent hair loss and problematic crusting[11]. The lice may be harder to clear as they may hide under crusts on the scalp; an antimicrobial emollient (e.g. Dermol 500 lotion) can be applied to the hair and scalp before being combed out with a fine-toothed comb[11]. If proprietary insecticides are used, all wounds and blister sites should be protected using a barrier agent (e.g. Vaseline) before application[11]. Ivermectin is a systemic oral agent that selectively binds to specific neurotransmitter receptors of the peripheral motor system of the lice, and can be an effective alternate therapy for patients who are resistant or cannot tolerate the therapy outlined above[11,24].

Future therapies

Different evidence-based approaches are being tested at pre-clinical and clinical levels for the most severe EB types and in some cases is focused on correcting the defective gene. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation improved symptoms in some patients but is associated with severe adverse effects, including death[6]. Intravenous infusions with mesenchymal stromal stem cells from bone marrow relieved symptoms, such as itch, and improved the general wellbeing of children, but was deemed not to have clear clinical benefit at this stage by NHS England and is hence not currently commissioned[25].

Beremagene geperpavec (B-VEC) is a gene therapy that delivers a healthy or working copy of the human COL7A1 gene directly to skin cells, using a modified virus (herpes simplex virus-1) as a carrier. The NICE guidance on B-VEC for treating wounds in people with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa is currently under evaluation[26]. It has been studied in a double-blind, intrapatient randomised, placebo-controlled trial in patients aged 6 months or older with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa[27]. At 3 and 6 months of treatment, the primary endpoint of achieving complete wound healing was more likely with topical administration of B-VEC than with placebo.

Other approaches are aimed at relieving the symptoms of EB. Topical diacerein showed promising results in a clinical trial by improving healing and reducing blister formation, owing to its anti-inflammatory properties and its protective effects against collagen destruction[28].

Role of pharmacists

EB patients require complex and tailored care plans throughout their lives. Medicine optimisation enables a patient-centred, holistic approach to maximise benefits from their treatment, improve medicines safety and adherence and reduce wastage[29]. Having an open dialogue to discuss symptoms/concerns with patients and/or their carers is crucial in agreeing on a care plan. EB patients will have a tried and tested dressing regimen and pain and pruritus management strategies that suit their needs (e.g. short-acting opioids for acute pain and sedative antihistamine to promote sleep and avoid scratching at night)[11]. Management should start with a thorough history to identify the timing and exacerbating factors and devise corresponding therapies.

Owing to the complexity and rarity of their diseases, EB patients’ care plans will involve polypharmacy and the use of unlicensed medicines[18,20,21,30]. Pharmacists can help patients and/or their carers to make informed decisions about their treatment choices by providing education and support regarding their medications.

The use of age-appropriate assessment tools — such as the behavioural Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability (FLACC) scale and visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain — can be helpful in identifying temporal patterns and aggravating factors to ensure personalised treatment that is clinically appropriate, cost-effective and informed by the best evidence available[31]. Stepdown plans should be an integral part of care plans to reduce drug burden and adverse drug effects and discontinue any treatments that do not benefit the patient’s management.

Summary

EB is a complex disease, with severe types having devastating effects on quality of life and life span. Patients with EB require the involvement of a dedicated multidisciplinary team with expertise in all aspects of care. Pain is the most common symptom, and it is essential that patients have an individualised care plan to ensure their pain is controlled. Until a cure is available, anticipatory guidance for possible disease-related complications and appropriate wound care are the cornerstones of EB management.

Best practice for pharmacists

- Medicine optimisation is essential for the successful management of EB patients to help them to live a near-to-normal life;

- Effective communication with various care providers to provide holistic multidisciplinary care, maximise treatment benefits and avoid adverse drug events;

- Respect EB patients’ preferences with an open-minded approach when helping them to formulate tailored skin care and symptom management strategies;

- Management of skin integrity, wound care, pruritus, pain and nutrition are essential components of care plans;

- Help patients to avoid drug–drug and drug–disease interactions that may impair wound management and result in harm;

- Consider patients’ existing pain management strategies when planning pain management for surgical interventions;

- Provide effective counselling to enable EB patients to make an informed decision regarding their treatment.

This article has been reviewed and updated by the expert authors to ensure it remains relevant, following its original publication in May 2021.

- 1Epidermolysis bullosa simplex patient information leaflet. British Association of Dermatologists. https://www.bad.org.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?id=163&itemtype=document (accessed April 2021)

- 2Clinical Practice Guidelines. DEBRA. https://www.debra.org.uk/healthcare-professionals/clinical-best-practice-guidelines (accessed April 2021)

- 3Epidermolysis bullosa. NHS. 2021. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Epidermolysis-bullosa/

- 4Epidermolysis bullosa. Primary Care Dermatology Society. http://www.pcds.org.uk/clinical-guidance/epidermolysis-bullosa1 (accessed April 2021)

- 5Denyer J. Managing pain in children with epidermolysis bullosa. Nurs Times. 2012;108:21–3.

- 6Bruckner-Tuderman L. Newer treatment modalities in epidermolysis bullosa. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:244.

- 7Fine J-D. Inherited epidermolysis bullosa. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-12

- 8Epidermolysis bullosa. DermNet NZ. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/epidermolysis-bullosa/ (accessed April 2021)

- 9Youssefian L, Vahidnezhad H, Uitto J. Kindler Syndrome. Adam M, Ardinger H, Pagon R et al. GeneReviews®. Seattle, USA. 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK349072 (accessed April 2021)

- 10Koga H, Prost-Squarcioni C, Iwata H, et al. Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita: The 2019 Update. Front Med. 2019;5. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00362

- 11Denyer J, Pillay E, Clapham J. Best practice guidelines for skin and wound care in epidermolysis bullosa. Wounds International. 2017. https://www.debra.org.uk/downloads/community-support/woundcare-guidelines-2017.pdf (accessed April 2021)

- 12Pope E, Lara-Corrales I, Mellerio J, et al. A consensus approach to wound care in epidermolysis bullosa. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2012;67:904–17.

- 13McDonald C, Plevey K, Petrof G, et al. <p>Optimal Management Of Chronic Wounds In Paediatric Junctional Epidermolysis Bullosa Patients</p>. CWCMR. 2019;Volume 6:99–107.

- 14Birch bark extract for treating epidermolysis bullosa. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/hst28 (accessed February 2024)

- 15Goldschneider KR, Good J, Harrop E, et al. Pain care for patients with epidermolysis bullosa: best care practice guidelines. BMC Med. 2014;12. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0178-2

- 16Medications and Herbs That Affect Bleeding. Stanford University School Of Medicine. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/ohns/documents/Sinus%20Center/Stanford_Medication_and_Herbs.pdf (accessed April 2021)

- 17Wong A, Townley SA. Herbal medicines and anaesthesia. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 2011;11:14–7.

- 18de Leeuw TG, Mangiarini L, et al. Gabapentin as add-on to morphine for severe neuropathic or mixed pain in children from age 3 months to 18 years – evaluation of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of a new gabapentin liquid formulation: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-3169-3

- 19Buck M. Gabapentin use in postoperative and neuropathic pain in children. Pediatr Pharmacother 2016;22(2). https://med.virginia.edu/pediatrics/wp-content/uploads/sites/237/2015/12/Feb16_Gabapentin_PedPharmaco.pdf (accessed April 2021)

- 20Cooper TE, Wiffen PJ, Heathcote LC, et al. Antiepileptic drugs for chronic non-cancer pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Published Online First: 5 August 2017. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd012536.pub2

- 21Kamerman P, Finnerup N, Lima LD, et al. Gabapentin for Neuropathic Pain: An application to the 21st meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on Selection and Use of Essential Medicines for the inclusion of gabapentin on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. 2020. https://doi.org/10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.3814206

- 22He A, Alhariri JM, Sweren RJ, et al. Aprepitant for the Treatment of Chronic Refractory Pruritus. BioMed Research International. 2017;2017:1–6.

- 23Bardhan A, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Chapple ILC, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0210-0

- 24BNF for children. London: BMJ Group, Pharmaceutical Press, and RCPCH Publications. Paediatric Formulary Committee. 2020. https://bnfc.nice.org.uk (accessed April 2021)

- 25Allogenic Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Infusion Therapy for Children with Severe Generalised Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa. NHS England Clinical Commissioning Policy Statement. 2019. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/allogenic-mesenchymal-stromal-cell-infusion-therapy-for-children-with-severe-generalised-recessive-dystrophic-epidermolysis-bullosa/ (accessed April 2021)

- 26Beremagene geperpavec for treating skin wounds associated with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/awaiting-development/gid-ta10868 (accessed February 2024)

- 27Guide SV, Gonzalez ME, Bağcı IS, et al. Trial of Beremagene Geperpavec (B-VEC) for Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:2211–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2206663

- 28Wally V, Hovnanian A, Ly J, et al. Diacerein orphan drug development for epidermolysis bullosa simplex: A phase 2/3 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2018;78:892-901.e7.

- 29Picton C, Wright H. Medicines Optimisation: Helping patients to make the most of medicines. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2013. http://www.rpharms.com/promotingpharmacy-pdfs/helping-patients-make-the-most-of-their-medicines.pdf (accessed April 2021)

- 30Chappell F. Medication adherence in children remains a challenge. Prescriber. 2015;26:31–4.

- 31Brun J, Chiaverini C, et al. Pain and quality of life evaluation in patients with localized epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0666-5