RICHARD USATINE MD / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article you should be able to:

- Recognise the signs and symptoms of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS);

- Understand the aims of pharmacological management of the disease;

- Be aware of the ways in which pharmacy professionals can support people with HS in managing their disease.

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic skin condition that causes painful inflammatory lesions in the folds of skin in areas of the body such as the armpits and groin, where hair follicles and apocrine sweat glands are present in abundance1.

As well as the pain and discomfort of the growths, patients struggle with the social impact of the disease, with HS patients experiencing an estimated 50% higher risk of depression and double the risk of suicide2,3. The appearance of deep-seated lesions can be unsightly and it can be embarrassing to have exudate leaking from the affected areas into clothing, with the fluid sometimes having an unpleasant odour as a consequence of pathogen infiltration4.

Compared with other follicular disorders, such as acne, HS is less well recognised by healthcare professionals. Prevalence is difficult to pinpoint owing to varied estimation methodologies and patients are often misdiagnosed, waiting years for a firm diagnosis5. Results from a 2018 study suggested that the condition may affect between 0.8–1.2% of the UK population2.

There is often a long diagnostic delay for patients; the average diagnostic delay for HS is 7.2 years5. Incorrect diagnoses owing to healthcare professionals’ unfamiliarity with HS and patient delay in seeking professional help are theorised as likely reasons6. Raising awareness of the disease among pharmacists and pharmacy technicians is one way in which this delay may be shortened.

Pathophysiology

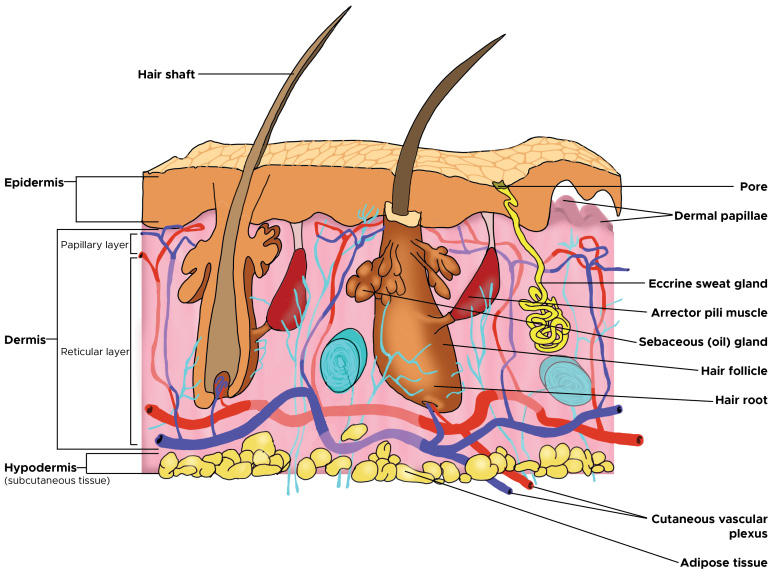

The name hidradenitis is a misnomer that derives from an outdated understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease: ‘hidrós’ means sweat, ‘adeno’ means gland and ‘itis’ refers to inflammation7. Despite HS lesions being found in locations that are dense with apocrine sweat glands, it is thought that the pathophysiology of the disease is not directly related to the glands, but instead resulting from inappropriate immune function, as well as blockages in hair follicles and their associated structures7.

Normal structure of the hair follicle can be seen in Figure 18, a suggested mechanism for the pathophysiology seen in HS can be seen in Figure 29.

Reproduced with permission from Martel et al.; StatPearls Publishing LLC

Smoking and obesity seem to contribute to disease progression by encouraging a pro-inflammatory environment; obesity can also contribute to increased mechanical stress and friction in the skin folds7. Despite many logical theories, a definitive pathophysiology of HS remains elusive.

Signs and symptoms

The clinical presentation of HS can vary, but the characteristic signs are painful inflamed nodules, papules and pustules, double-ended pseudocomedones (blackheads) and cysts that merge together to form draining sinuses4. Lesions can join together, forming tunnels under the skin and leaving scars and painful rope-like tethers of scar tissue1.

The armpits, groin and under the breasts are common locations for lesions to develop; these are areas where friction regularly occurs during movement. Their warmth, plus the combination of high moisture levels and low oxygen permeability, appear to help the proliferation of anaerobic bacteria, the presence of which may trigger the inflammatory response at the start of a HS lesion1.

The affected areas are typically hidden under clothing, which can make it difficult to identify a potential case of HS in a pharmacy setting, unless a patient proactively seeks advice. Pharmacists can help support patients in appropriate use of over-the-counter pain management and the selection of dressings, which will be discussed in more detail later.

Unfortunately, scarring is common and can be just as debilitating as active HS lesions themselves in high-grade disease. Patients develop hypertrophic and bridging scars that rigidly connect skin on the inside of joints, potentially limiting range of motion in the limbs4. Scar tissue can be extensive and can have a significant impact on quality of life10.

Risk factors

Studies have found that women are three times more likely than men to be diagnosed with HS in Europe and North America2,11. It is more common in people with skin of colour; US studies have shown people from racial and ethnic minority groups have a higher prevalence of HS and greater disease morbidity12. There also appears to be a genetic link; family history is reported in around one-third of patients5. A history of other follicular disorders, such as acne and pilonidal sinus, as well as diseases of immune dysregulation, such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and psoriasis, have been found to have an association with HS5.

HS patients are more than three times more likely than the general population to smoke or have obesity, making these the two biggest modifiable risk factors for the disease2. Smoking cessation and support in weight loss are areas where community pharmacy teams can be of great help, through advanced services, counselling and signposting to other NHS resources. However, expectation management is important. Although positive changes to these risk factors can reduce disease severity in patients, it is not a silver bullet and HS is still found in patients who are non-smokers, and in those of a healthy weight4.

Diagnosis and grading

HS is usually a clinical diagnosis owing to characteristic lesion sites/morphological features, strong links to family history of the disease and association with other follicular or immune function disorders13. Comprehensive history-taking and physical examination are, therefore, critically important. Histological investigation is uncommon, as it is difficult to distinguish the disease from other inflammatory skin conditions under the microscope14. More information on diagnosis can be found in the British Association of Dermatologists’ HS 2018 guideline4.

Once a diagnosis has been made, there are many severity scoring systems available to clinicians; however, the Hurley staging system is most widely used in the UK (see Table 14). Severity scoring systems are important to monitor disease progression and for effective communication between primary, secondary and tertiary care teams when progressing to more specialist treatment options with complex funding arrangements.

There are various differential diagnoses for HS. What might appear superficially to be HS, could be cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease, staphylococcal infection or cysts7. Prompt signposting of patients to general practice and specialist services is the most suitable approach for pharmacists to take. The intimate location of many HS growths means that axillary lesions are the only common lesion site that would be appropriate to examine in the consultation room of a community pharmacy.

Management

Treatment regimens can be complex and may involve drugs with important counselling points. Patients may need to be reviewed each month or so during the initiation of a treatment, but this can become more infrequent once stabilised (perhaps every three to six months instead)4. In hospital dermatology services, pharmacists can support access to new treatment options, such as monoclonal antibodies15,16. They can also directly engage with and prescribe for patients in clinics and encourage other clinical staff in the department to adhere to step-wise treatment pathways based on national guidance4, supporting patients in finding the best treatment regimen for their disease.

Treatment success is assessed based upon reduction in pain and lesion count, more infrequent disease flares and by improved scores on quality-of-life questionnaires4.

Conventional therapies

Patients often cycle through a variety of pharmacological interventions in pursuit of relief from HS. Antibiotics feature prominently in the treatment algorithm from the British Association of Dermatologists4. The mechanism by which antibiotics alleviate HS may be as much owing to their anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects as their antimicrobial function17.

The benefit of long courses of antibiotics (i.e. more than 14 days) for the individual patient, combined with the chronic nature of HS, presents a dilemma: while some patients are keen to use an antibiotic on an ongoing basis, antimicrobial stewardship is increasingly important and pharmacists should challenge open-ended use of antibiotics in this patient group. That is not to say that an individual should be limited to a set number of courses in a lifetime, but antibiotic regimens should have a defined endpoint and only be reinitiated in times when symptoms flare4.

There are some notable adverse effects for systemic HS regimens. Pharmacists can counsel patients on the important safety points and ensure suitability. Generally, the least intense and most cost-effective options are tried in the first instance, progressing to more intensive options in later lines of treatment, requiring careful consideration as to the balance of risks versus benefits. This is explored in Table 24,18–23.

The monoclonal antibodies adalimumab and secukinumab, which are the last lines of treatment, require centrally commissioned NHS funding15,16,24. They can be used only when conventional systemic therapies have failed. Their benefit in HS is mediated through effects on inflammatory pathways (affecting the cytokines tumour necrosis Factor α and Interleukin 17, respectively)24. The treatments are suitable for shared care between secondary and tertiary care15,16. However, the mechanism for ensuring appropriate reimbursement can be confusing for clinical teams. Pharmacists can make use of their expert knowledge on funding pathways to make sure that costs are appropriately reimbursed. By enabling shared care, pharmacists can make it easier and more convenient for patients to be supported by their local dermatology team, rather than having to be managed by a more distant specialist centre.

Pain management

Pain is considered to be the most impactful symptom of HS for many patients25. There is currently no clear consensus on optimal pain management and there is a pressing need for research to understand the causes of HS pain. Pain in HS appears to involve a combination of both neuropathic and nociceptive pathways26. Pharmacists can support patients in finding relief with over-the-counter products, such as oral or topical NSAIDs, given the inflammatory nature of the disease, or with topical methol (a medication that relieves pain by causing the skin to feel cool and then warm), which can be soothing when used on impacted sites27.

Paracetamol can be useful in mild pain; however, refractory pain may require prescription-only medicines, such as gabapentin, tricyclic antidepressants or opioids27. Involvement of specialist pain teams is prudent, given the potential for dependency with these more intensive options. Healthcare professionals should also bear in mind that an individual’s experience of pain does not necessarily correlate with the outward markers of disease severity.

Self-care advice

Patients can also benefit from other treatment modalities and lifestyle adjustments. Some patients find the use of an antiseptic wash such as chlorhexidine 4% solution beneficial as a soap substitute4. Avoiding tight-fitting clothing that could otherwise add to friction and occlusion can help some patients. A system of dressings and custom garments called Hidrawear is available on some formularies in the UK, which has been developed to reduce friction and incorporates dressings that lock into place at common HS lesion sites28. Patients who require additional support with wound care can be signposted to speak with specialist dermatology nurses or members of the local tissue viability team, who are best placed to provide expert individualised advice. As a general guide, the most suitable dressings for HS are usually those that have high absorbance and low friction. Charcoal dressings can also help manage odour29.

Surgery

Surgery is used to remove chronic lesions that have not responded to medical intervention and to address sequelae, such as scars, contractions of the skin and sinus tracts24. Novel surgical techniques are evolving to suit the morphological characteristics of HS, such as de-roofing, in which the roof of a lesion is excised. This can save tissue and reduce lesion recurrence30. Marsupialisation is another procedure whereby the surgeon crafts a pocket of tissue at a lesion site with an intentional opening that the patient can manually manipulate to easily drain exudate at a convenient time, reducing pain from fluid build-up and minimising the risk of embarrassing leakages in social situations10. Patients can experience complications as a consequence of surgery, with the potential for infection and nerve damage. Scar tissue from the surgery itself might still limit the range of motion of limbs7. There is evidence to suggest that specialist surgical techniques lead to low levels of recurrence for the lesion that has been operated on; however, there is always the risk of new lesions developing in the future31.

Complications and patient prognosis

HS patients have an elevated risk of squamous cell carcinoma owing to chronic inflammation7. Medical interventions are not without risk, as shown in Table 2. Monitoring for adverse events when using intensive treatments is important. There is significant overlap between the disease and comorbidities, such as cardiovascular problems, atherosclerosis, metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidaemia4,7.

Conclusion

The past 20 years have revolutionised the pharmacological landscape for other inflammatory dermatoses, such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, with a wealth of effective, targeted treatment options now on offer32. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for HS. Although new treatment options, such as monoclonal antibodies, are promising, managing expectation in patients while still being able to elicit the enthusiasm to pursue different treatments is a delicate balancing act. Identification and early treatment of HS can reduce the likelihood of developing severe disease6.

- 1.Wolk K, Join‐Lambert O, Sabat R. Aetiology and pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(6):999-1010. doi:10.1111/bjd.19556

- 2.Ingram JR, Jenkins-Jones S, Knipe DW, Morgan CLI, Cannings-John R, Piguet V. Population-based Clinical Practice Research Datalink study using algorithm modelling to identify the true burden of hidradenitis suppurativa. British Journal of Dermatology. 2018;178(4):917-924. doi:10.1111/bjd.16101

- 3.Thorlacius L, Cohen AD, Gislason GH, Jemec GBE, Egeberg A. Increased Suicide Risk in Patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2018;138(1):52-57. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2017.09.008

- 4.Ingram JR, Collier F, Brown D, et al. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for the management of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa) 2018. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(5):1009-1017. doi:10.1111/bjd.17537

- 5.Ingram JR. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa*. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(6):990-998. doi:10.1111/bjd.19435

- 6.Saunte DM, Boer J, Stratigos A, et al. Diagnostic delay in hidradenitis suppurativa is a global problem. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(6):1546-1549. doi:10.1111/bjd.14038

- 7.Vinkel C, Thomsen S. Hidradenitis Suppurativa: Causes, Features, and Current Treatments. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(10):17-23. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30519375

- 8.Martel J, Miao J, Badri T, Fakoya A. statpearls. Published online June 22, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470321/

- 9.Vossen ARJV, van der Zee HH, Prens EP. Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Systematic Review Integrating Inflammatory Pathways Into a Cohesive Pathogenic Model. Front Immunol. 2018;9. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02965

- 10.Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: A publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2019;81(1):76-90. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.067

- 11.Garg A, Kirby JS, Lavian J, Lin G, Strunk A. Sex- and Age-Adjusted Population Analysis of Prevalence Estimates for Hidradenitis Suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(8):760. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0201

- 12.Jaleel T, Mitchell B, Burge R, et al. Exploring racial and ethnic disparities in the hidradenitis suppurativa patient disease journey: Results from a real‐world study in Europe and the USA. The Journal of Dermatology. Published online October 14, 2024. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.17386

- 13.Ingram JR. The Genetics of Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Dermatologic Clinics. 2016;34(1):23-28. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.07.002

- 14.Smith SDB, Okoye GA, Sokumbi O. Histopathology of Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Systematic Review. Dermatopathology. 2022;9(3):251-257. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9030029

- 15.TA392: Adalimumab for treating moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2016. Accessed November 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta392

- 16.TA935: Secukinumab for treating moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023. Accessed November 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta935

- 17.Ring HC, Riis Mikkelsen P, Miller IM, et al. The bacteriology of hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. Experimental Dermatology. 2015;24(10):727-731. doi:10.1111/exd.12793

- 18.Dalacin T Topical Lotion or Clindamycin Phosphate Topical Lotion – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2024. Accessed November 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/3844/smpc

- 19.British National Formulary. British National Formulary. Accessed November 2024. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/

- 20.Wakelin SH, Maibach HI, Archer CB, eds. Handbook of Systemic Drug Treatment in Dermatology. CRC Press; 2015. doi:10.1201/b18491

- 21.Singh S, Sethi N, Pandith S, Ramesh G. Dapsone-induced methemoglobinemia: “Saturation gap”-The key to diagnosis. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2014;30(1):86. doi:10.4103/0970-9185.125710

- 22.DeMeulenaere S. Pulse Oximetry: Uses and Limitations. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2007;3(5):312-317. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2007.02.021

- 23.Kiniwa N, Okumiya T, Tokuhiro S, Matsumura Y, Matsui H, Koga M. Hemolysis causes a decrease in HbA1c level but not in glycated albumin or 1,5-anhydroglucitol level. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation. 2019;79(6):377-380. doi:10.1080/00365513.2019.1627577

- 24.Ocker L, Abu Rached N, Seifert C, Scheel C, Bechara FG. Current Medical and Surgical Treatment of Hidradenitis Suppurativa—A Comprehensive Review. JCM. 2022;11(23):7240. doi:10.3390/jcm11237240

- 25.Orenstein LAV, Salame N, Siira MR, et al. Pain experiences among those living with hidradenitis suppurativa: a qualitative study. British Journal of Dermatology. 2022;188(1):41-51. doi:10.1093/bjd/ljac018

- 26.Nielsen RM, Lindsø Andersen P, Sigsgaard V, Theut Riis P, Jemec GB. Pain perception in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. Published online July 8, 2019. doi:10.1111/bjd.17935

- 27.Savage KT, Singh V, Patel ZS, et al. Pain management in hidradenitis suppurativa and a proposed treatment algorithm. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2021;85(1):187-199. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.039

- 28.HidraWear – Wound care solution, adhesive free for hidradenitis suppurativa. HidraWear. Accessed November 2024. https://hidrawear.com/

- 29.Hidradenitis Suppurativa – Primary Care Treatment Pathway. Primary Care Dermatology Society. 2024. Accessed November 2024. https://www.pcds.org.uk/files/general/hs-pathway-web.pdf

- 30.van der Zee HH, Prens EP, Boer J. Deroofing: A tissue-saving surgical technique for the treatment of mild to moderate hidradenitis suppurativa lesions. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2010;63(3):475-480. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.12.018

- 31.Chawla S, Toale C, Morris M, Tobin A, Kavanagh D. Surgical Management of Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Narrative Review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(1):35-41. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35309275

- 32.Smith CH, Yiu ZZN, Bale T, et al. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for biologic therapy for psoriasis 2020: a rapid update. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(4):628-637. doi:10.1111/bjd.19039