Medication errors affect babies in more than half of England’s neonatal units, from incorrect dosing that poses a risk to fragile newborns, to sub-optimal treatment that lengthens hospital stays. However, pharmacists often do not have the dedicated time they need to perform their specialised role supporting patients and families on neonatal and paediatric intensive care wards.

In 2022 and 2023, the Neonatal and Paediatric Pharmacy Group (NPPG) set out the level of pharmacist staffing required per bed to provide “appropriate support for the safe and effective use of medicines” in neonatal and paediatric critical care.

However, in 2025, there remains huge variability in pharmacist staffing, particularly in neonatal care and district general hospitals, as revealed by Freedom of Information (FOI) requests sent by The Pharmaceutical Journal to every hospital trust and health board in Great Britain.

Neonatal care

In neonatal care, pharmacists provide expertise in parenteral nutrition (i.e. intravenous nutrition infusions) and medication dose adjustments for babies who may be very small or have under-developed organs owing to prematurity. Levels of care range from neonatal intensive care units (NICU) and high dependency units (HDU), to special care baby units (SCBU; see Table 1). Some hospitals also have transitional care beds, which are used until an infant can be moved to more intensive care elsewhere.

For a five-day service, NPPG standards recommend 0.12 whole-time equivalent (WTE) pharmacists for every NICU bed, every two HDU beds, or every four SCBU beds.

Table 1: Levels of neonatal care

But the majority of NHS hospital trusts and health boards told The Pharmaceutical Journal that they did not have enough pharmacists to meet these ratios on neonatal wards, with particularly low levels where pharmacists were supporting neonatal care in addition to work across maternity and children’s wards.

Of the 125 NHS hospital trusts with neonatal beds that responded to The Pharmaceutical Journal’s FOI request (see Box), just 13% (n=16) met the NPPG staffing standards for neonatal pharmacy, 7% (n=9) almost or possibly did (for instance, depending on allocation of staff time), and 75% (n=94) did not meet the standards.

In a further 4% (n=5) of trusts, some sites did meet the standards and some did not.

Figure 1: Very few NHS trusts meet the Neonatal and Paediatric Pharmacy Group staffing standards for neonatal care

Medicines safety

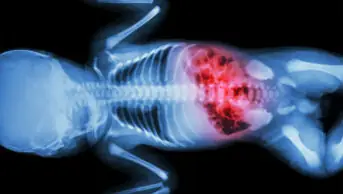

Low pharmacist staffing puts medication safety at risk, which is particularly concerning given how frequently medication errors are reported in neonatal intensive care.

According to the results of a 2019 survey carried out by NHS England’s Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) project and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH), medication errors were the most common incident reported in 28% of NICUs, 51% of LNUs and 8% of SCBUs (see Table 2).

The results also revealed that medication errors were among the top three incidents reported in 62% of centres for all levels of neonatal intensive care.

Table 2: Medication errors in neonatal intensive care

Nigel Gooding, a neonatal pharmacist and regional lead for NPPG, highlights how crucial pharmacist skills are to adjust doses for very small babies with different physiology to adult or even paediatric patients.

Compared to adult care, “you really do use your brain more [in NICU] in terms of why we’re using these drugs”, he explains.

“What are the doses that we should be using, how are you adapting that for a [neonatal] patient, how are we even going to get this medicine into a neonate in some cases? Often there’s not a black and white answer for some of these things, and it’s just having that ability to think outside the box, and use the evidence that we do know and then trying to adapt it to the situation.”

Without proper pharmacist involvement, Gooding warns that babies might be given too much medication or vitamins or be treated sub-optimally with too low a dose. This might mean patients and their families have to stay in hospital for longer, while higher intensity cots cannot be freed up for other patients.

NHS England says it aims to “provide safe expert care as close to their home as possible, and keep mother and baby together while they need care”, but a lack of cot capacity at the right level of care can mean babies have to be moved away from their local hospital or even out of region.

This has an “absolutely massive” impact on the family, particularly with limited access to family accommodation, says Gooding.

“The capacity issues are massive in neonates,” he says, adding that his own hospital is “full at the moment”.

Ward rounds

The NPPG standards recommend that pharmacists “must attend daily multidisciplinary ward rounds”, which could lead to reduced mortality, shorter stays and fewer adverse drug events. The RCPCH has also highlighted pharmacists as crucial members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT), saying: “Paediatric pharmacist reviews have been associated with reduced medication incidents.”

Involvement in multidisciplinary ward rounds are where pharmacists can have the “maximum impact” as they are able to review patients frequently and correct errors, respond to concerns and optimise medication swiftly, says Gooding.

“You’re there as they’re discussing the baby and what the plan is for the next 24 hours. Without that, you’re playing catch-up sometimes, it’s quite hard,” he explains.

But responses to The Pharmaceutical Journal’s FOI request show that pharmacist attendance on ward rounds in neonatal care is varied (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Where do pharmacists attend daily MDT neonatal ward rounds?

Just over one-quarter (27%; n=34) of the trusts and health boards with neonatal beds we surveyed do ask pharmacists to attend daily ward rounds. Some of these trusts house specialist centres such as St George’s Hospital and Great Ormond Street in London, and Sheffield Children’s Hospital in Yorkshire.

There can also be differences between sites within the same trust. For example, in Manchester’s St Mary’s Hospital Oxford Road Campus NICU, pharmacists do not attend daily MDT ward rounds, but pharmacists working in Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, which is operated by the same trust, do.

Other trusts say pharmacists attend “sometimes”, with the University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust telling The Pharmaceutical Journal: “Current capacity doesn’t allow daily attendance on ward rounds.”

Overall, in 22 trusts (18%) surveyed that had neonatal care, pharmacists attended ward rounds sometimes but less than daily, or attended MDT ward rounds in some sites but not others within the trust.

Meanwhile, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, which operates a NICU and two paediatric intensive care units (PICUs), including at London’s Evelina Children’s Hospital, said: “Attendance to full rounds is not necessarily the best way to optimise pharmacist time.”

Instead, it has its pharmacists attend ward rounds twice weekly and participate in MDT discussions on specific patients “where medicines optimisation is complex and critical”.

As regional lead for the East of England at the NPPG, Gooding says: “I don’t think we’ve got anywhere in the region that’s got enough staffing to be able to attend a ward round, or at least regularly attend a ward round.”

Overall, 53% (n=66) of trusts with neonatal beds said pharmacists did not attend daily MDT ward rounds.

‘The non-patient-facing part of the job is what suffers’

As well as medication safety, the NPPG standards are aimed to enable pharmacists to provide “value-added” clinical care, says Stephen Tomlin, professional lead at the NPPG.

It is this non-patient facing element of the job — such as team management, dispensary, stock, developing guidelines and resources and undertaking their own training — that “tends to be the bigger part that suffers a bit more, that you have to postpone”, says Sylvia George, paediatric critical care pharmacist at Oxford University NHS Foundation Trust.

Pharmacists might provide medication-related training for other members of the MDT, including junior doctors, or initiate projects such as switching eligible newborns to oral antibiotics at home.

Existing workforce assessments often fail to quantify the contribution that pharmacists make. For instance, Gooding suggests that the 2022 GIRFT neonatal workforce report focused more on the need for allied health professionals because pharmacists were already seen to be on intensive care wards – even if in reality, their role was split across wider women’s and children’s units and did not allow them to provide value-added patient care.

Is pharmacist staffing better in paediatric intensive care units?

“Pharmacy should never be seen as an optional extra, but an essential part of the team. Pharmacy needs to make it much clearer about what they deliver and how many are needed to deliver that service and stick to that (the same as groups such as nurses),” says Tomlin.

The data collected by The Pharmaceutical Journal suggest this seems to have been the case in specialist PICUs, which generally provide both level three (L3) and level two (L2) care for sick children (see Table 3).

Table 3: Levels of paediatric critical care

The Pharmaceutical Journal’s investigation found that sites with L3 PICU beds (n=20) were the best resourced in terms of pharmacist staffing: 40% (n=8) of trusts with level three (L3) paediatric critical care beds met the NPPG staffing ratio, 15% (n=3) nearly or probably did (depending on staffing allocations) and 40% (n=8) did not (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Level 3 paediatric intensive care settings have the highest pharmacist-to-bed ratio

The trusts that did meet the ratios include Alder Hey Children’s Hospital in Liverpool, which has a team of pharmacists available to meet its 4.5 WTE requirements for a 36-bed seven day service; and Great Ormond Street Hospital in London, which has a 1.2 WTE band 8 pharmacist and 1 WTE band 7 pharmacist to cover its 17 L3 beds.

However, at the Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, just 0.3 WTE band 8b and 0.8 WTE band 8a pharmacists are employed to cover paediatric critical care — not enough to meet the standards for 19 L3 and 14 L2 beds.

At Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, one site – the Evelina Children’s Hospital – met the staffing ratios required, but another site, the Royal Brompton Paediatric Intensive Care Unit, did not.

Some hospital trusts only provide L2 paediatric intensive care (see Table 3, above) alongside general paediatric wards, and do not have a specialised PICU (n=26).

In these cases, our investigation suggests pharmacists are often covering several departments and therefore may not be able to devote enough time to the critical care beds (see Figure 4). One-quarter of trusts that only offered L2 paediatric critical care were categorised by The Pharmaceutical Journal as ‘orange’ — those that nearly or possibly met the standards, depending on staffing allocation across different departments (27%, n=7).

Figure 4: Outside of specialist PICUs, pharmacist time on paediatric critical care is more mixed

Less than one-third (27%, n=7) of trusts with just L2 beds met the NPPG ratio, while 42% (n=11) did not. In one trust — University Hospitals Sussex NHS Foundation Trust — pharmacist-to-bed ratios in one half of the trust (St Richard’s Hospital in Chichester and Worthing Hospital) met the standards, while ratios for beds that had formerly fallen under East Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust did not.

George explains that it can be hard to make a case for needing more pharmacists if a hospital has just a few beds requiring a higher level of care.

“You need to have quite a high skill mix and yet you’re investing it for a smaller number of patients,” she says.

“In the bigger picture of the NHS and staffing, that’s where the struggle tends to be. It’s like: ‘Why do you need a specialist pharmacist for a ten-bed unit?’.

“PICUs that are exclusively within a children’s hospital have it a bit easier with trying to get better staffing, compared to university hospitals where it’s really big and paediatrics tend to be a smaller part,” she adds.

Ward-based pharmacy technicians

One way to increase pharmacist capacity might be to make more use of pharmacy technicians. The NPPG standards suggest that ward-based pharmacy technicians “can provide a valuable supportive role, assisting with activities such as medicines reconciliation, medicines management and expenditure reporting … which can release more time for medicines optimisation activities by clinical pharmacists”.

Responding to our FOI requests, just 15% (n=19) of hospital trusts that had L2 or L3 paediatric critical care or NICU, HDU or SCBU neonatal care employed ward-based pharmacy technicians (see Figure 6).

Figure 5: Very few hospital trusts employ ward-based pharmacy technicians

Ashifa Trivedi, senior paediatrics pharmacist at Evelina London Children’s Hospital, says the role of pharmacy technicians is “often underestimated”.

“Ward-based pharmacy technicians can play an important part in supporting safe and effective medicines use — helping with medicines reconciliation, patient and parent counselling, monitoring for interactions, and advising on administration through enteral feeding tubes.

“Their involvement allows pharmacists to focus on the more complex clinical and governance aspects of care,” she adds.

Tomlin agrees: “Pharmacy technicians can deliver so much of the medicines management programme and their absence generally leads to pharmacists delivering more service delivery functions and less directed clinical care.”

Funding and recognition

Ultimately, though, more pharmacist roles are needed to improve medicines safety and patient care — particularly as more of the workforce become prescribers.

“Medicines and medicine practice are, ever increasingly, complex; the pharmacy team are in a unique position of having a primary focus on those complexities,” Tomlin explains.

“Not having that dedication on medicine training, education and leadership can only be at the detriment to the delivery from the rest of the MDT and the outcome of the patients.

“There is a logic to having all pharmacists being able to prescribe medicines in the future — medicines are what we do.”

Trivedi says pharmacy should be “integral” to service design and workforce planning, which would “support more equitable, safe, and sustainable care for children across both specialist and district general hospitals”.

However, even though the NPPG standards set out a level to aim for, “meeting them is difficult without sustained investment, protected time, and visibility of the workforce in national planning”, Trivedi adds.

“It is not just about having the standards — it is also about enabling services to achieve them.”

Box: Freedom of Information requests

The Pharmaceutical Journal sent Freedom of Information requests to 155 hospital trusts and health boards across England, Wales and Scotland, 6% of which (n=10) did not respond.

Of those that did respond, 20 (14%) did not have any neonatal beds, but 126 had either neonatal care or level two or three paediatric critical care beds. Of those, 125 (99%) had neonatal care (NICU, HDU or SCBU); 26 (21%) had level two paediatric critical care beds but not level three, and a further 20 (16%) had level three paediatric critical care beds.

- This article was updated on 2 December 2025 to amend the number of hospital trusts that met the NPPG staffing standards for neonatal pharmacy as the FOI data provided from Aneurin Bevan was incorrect