Shutterstock.com

Premature infants face a unique set of health challenges, with the gastrointestinal (GI) system being particularly vulnerable owing to its immaturity. The under-developed digestive tract and immune system of preterm neonates predispose them to a range of GI complications, including necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD), feeding intolerance and malabsorption disorders1. These conditions can significantly impact growth, development and overall survival, making early recognition and appropriate management essential.

Pharmacists play a crucial role in optimising medication therapy, ensuring safe and effective treatment strategies, and providing guidance on nutritional support for these fragile patients. This article focuses on feeding and necrotising enterocolitis (NEC). Other GI complications are outside the scope of this article. Further information on the management of gastro-intestinal reflux disease (GORD) can be found here.

Gastrointestinal challenges in neonates

Premature neonates face significant GI challenges owing to the immaturity of their digestive system. Several factors contribute to their difficulty in processing and absorbing nutrition effectively:

- Underdeveloped GI tract: The intestines, stomach and digestive enzymes are immature, leading to impaired digestion and absorption of nutrients. The mucosal barrier is weak, making the gut more susceptible to inflammation and damage. There is reduced gastric acid secretion, which increases the risk of bacterial overgrowth and infection2;

- Delayed gastric emptying and motility issues: Preterm infants often have slow gastric emptying and uncoordinated intestinal contractions, leading to feeding intolerance, reflux and difficulty advancing to full enteral nutrition3;

- Inadequate enzyme production: Digestive enzymes, such as lactase, lipase and proteases, may be insufficient, affecting the breakdown of macronutrients such as fats, proteins and carbohydrates, leading to malabsorption and poor weight gain4;

- Increased risk of NEC: Preterm infants are highly susceptible to NEC, a condition characterised by severe inflammation and tissue death in the intestines, which may potentially be exacerbated by formula feeding and bacterial imbalances5. NEC is described in more detail below;

- Immature gut barrier and immune system: The neonatal gut has increased permeability, making it more prone to infections and conditions such as NEC6;

- Difficulty with enteral feeding: Many preterm infants require parenteral nutrition (IV feeding) initially because they cannot tolerate full enteral feeds. Early enteral feeds can lead to abdominal distension, increased gastric residuals and vomiting, which may raise concerns for NEC; however, prolonged reliance on parenteral nutrition can lead to complications, such as cholestasis and liver dysfunction7;

- Poor nutrient reserves: Preterm neonates miss out on the final weeks of gestation, a critical period for nutrient accumulation. They are often born with low stores of essential nutrients, such as iron, calcium and fat-soluble vitamins, making postnatal nutrition even more challenging8.

These factors combined make it difficult for premature infants to achieve adequate growth and nutrition, necessitating specialised feeding strategies, close monitoring and often pharmacologic interventions to support digestion, absorption and overall GI health.

Parenteral nutrition

According to recommendations published by the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN), preterm and term babies have different energy and nutrient intake requirements when on parenteral nutrition, owing to differences in growth rates, metabolic needs and organ immaturity9. These differences are illustrated in Table 19.

Preterm infants require more energy, protein and micronutrients to support catch-up growth and organ development10. Lipid intake is more critical in preterm infants owing to immature fat stores and higher essential fatty acid needs11. Electrolyte needs are higher in preterms owing to renal immaturity and higher rates of growth and bone mineralisation12. Parenteral nutrition for preterms must be carefully monitored to prevent metabolic imbalances and optimise growth13.

It can be a challenge to deliver enough nutrition to meet these needs through both parenteral and enteral nutrition, especially in the context of infants being fluid-restricted or having a reduced volume available for nutrition owing to other infusions, such as analgesia or inotropes14. One of the most important roles of a pharmacist on a neonatal unit is in the provision of parenteral nutrition, which may be required until enteral feeding can be established.

Delays in establishing enteral feeds in preterm neonates occur as a result of several physiological, medical and clinical factors related to their immaturity and vulnerability15,16. These reasons include the immaturity of the GI system and risk of NEC, as described above. Additional reasons include:

- Poor gut perfusion. Conditions such as hypotension, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) or perinatal asphyxia can reduce blood flow to the intestines, increasing the risk of ischaemia and feeding complications17,18;

- Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS). Many preterm babies require mechanical ventilation or CPAP, which can impact feeding tolerance19;

- The suck-swallow-breathe coordination typically matures around 32–34 weeks gestation, making direct oral feeding difficult in very preterm infants20;

- Risk of aspiration is higher owing to weak airway protective reflexes21;

- Some NICUs adopt a conservative feeding approach (slow advancement of feeds) to reduce risks of feeding intolerance and NEC22.

While delays in enteral feeding reduce immediate risks, prolonged parenteral nutrition dependency can lead to intestinal atrophy, increased infection risk (sepsis) and delayed gut maturation23. Minimal enteral feeding (MEF) or trophic feeds (small volumes of milk) are often introduced early to stimulate gut maturation while balancing risks24.

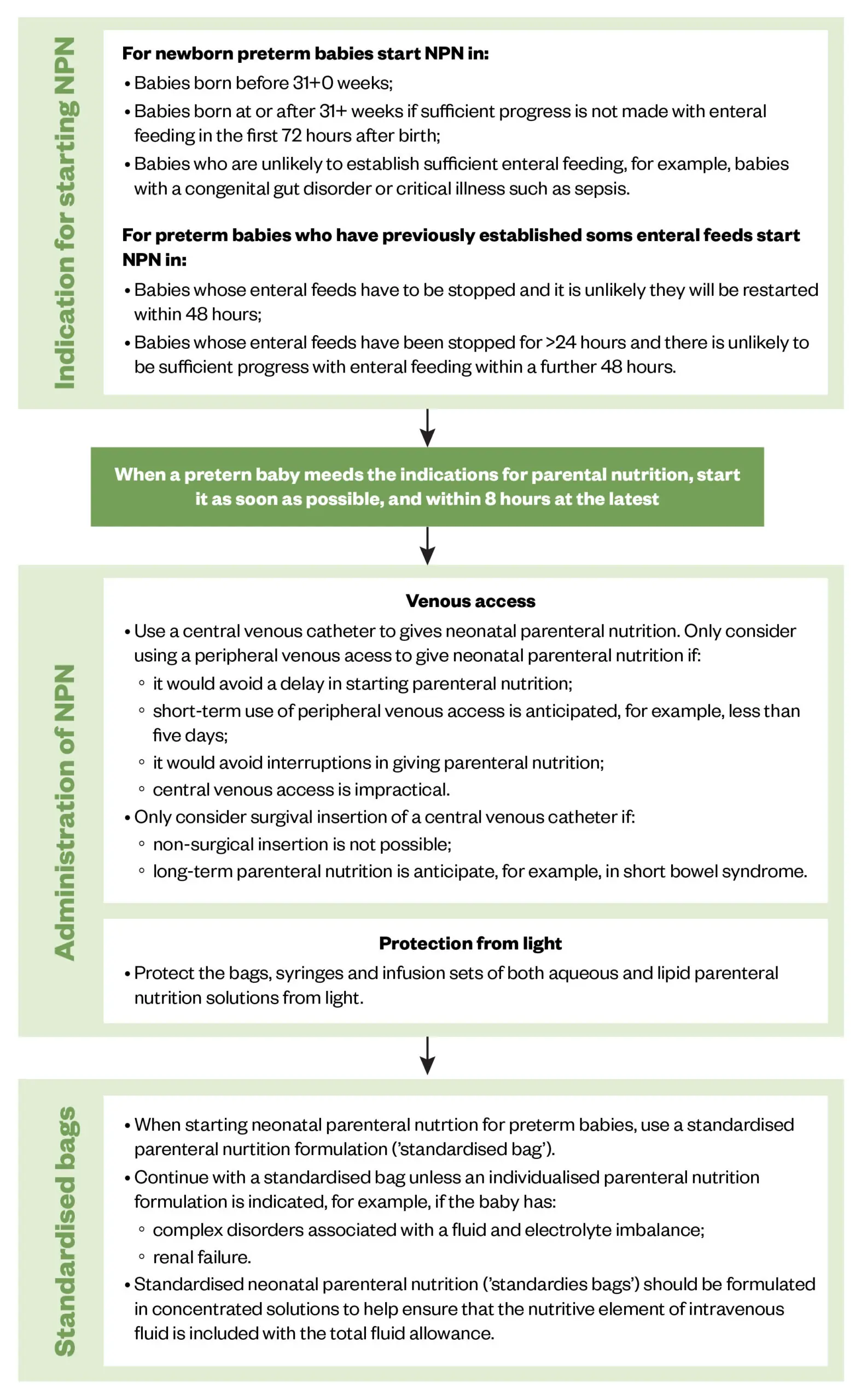

In 2020, the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) published a guideline on neonatal parenteral nutrition25. These recommendations can be applied by pharmacists, working alongside other neonatal healthcare professionals to ensure that babies’ nutritional needs are met. Figure 1 summarises when and how parenteral nutrition should be prescribed and administered in preterm babies aged up to 28 days25. An alternative algorithm for term babies can be found on the NICE website.

Adapted from NICE

The goal of parenteral nutrition is to ensure nutritional support is initiated as soon as necessary to promote and maintain optimal growth and development and reduce the risk of nutrient deficiencies. Parenteral nutrition contains the nutrients, vitamins and minerals a preterm neonate requires, the constituents of parenteral nutrition can be seen in Table 2 and Box 125.

Box 1: Other constituents of neonatal parenteral nutrition

- Iron:

- Do not give intravenous parenteral iron supplements to preterm babies <28 days old;

- For preterm babies 28 days or older, monitor for iron deficiency and treat if necessary.

- Give daily fat-soluble and water-soluble vitamins (in the IV lipid emulsion) from the outset or as soon as possible after starting parenteral nutrition;

- Give sodium and potassium in parenteral nutrition to maintain standard daily requirements;

- Give magnesium in parenteral nutrition from the outset or as soon as possible after starting parenteral nutrition;

- Give daily trace elements from the outset or as soon as possible after starting parenteral nutrition;

- For preterm babies with parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease, consider giving a composite lipid emulsion rather than a pure soy lipid emulsion25.

Monitoring

The recommendations from NICE for the monitoring of babies receiving parenteral nutrition can be seen in Table 325.

There are many factors to consider when deciding when to stop parenteral nutrition; examples include tolerance of enteral feeds and the needs of individual babies (e.g. short bowel syndrome)26. Please see the NICE guidance for additional information on stopping parenteral nutrition25.

Complications associated with parenteral nutrition can be seen in Box 2.

Box 2: Complications associated with parenteral nutrition

- Line complications:

- Line sepsis;

- Pneumothorax;

- Line dislodgement, fracture, leaking, blockage;

- Thrombosis and phlebitis;

- Loss of vascular access.

- Short-term metabolic complications:

- Hyper-/hypoglycaemia;

- Electrolyte abnormalities/refeeding syndrome;

- Hypertriglyceridemia;

- Over-hydration, oedema.

- Long-term metabolic complications:

- Metabolic bone disease;

- Intestinal failure associated liver disease;

- Micronutrient imbalances26.

Standardised parenteral nutrition

Standardised parenteral nutrition refers to approaches in which the parenteral nutrition solutions are manufactured according to a pre-specified standard formulation25. With individualised parenteral nutrition formulations, aqueous and lipid parenteral nutrition solutions are manufactured to meet the nutritional requirements of an individual baby. They are not pre-formulated and have to be prescribed and made up each time they are needed. Electrolytes can be added and macronutrients or micronutrients can be adjusted as necessary.

The responsibility for preparing individualised parenteral nutrition formulas for neonates typically falls under the neonatal multidisciplinary team, in collaboration with specialist hospital pharmacy aseptic units. Key roles in parenteral nutrition preparation are outlined in Table 4.

Some large NHS hospitals have their own aseptic pharmacy units for in-house parenteral nutrition compounding; however, most UK hospitals outsource parenteral nutrition preparation to specialist compounding facilities (e.g. commercial aseptic manufacturing units) to ensure consistency and sterility25.

Standard bags are recommended for routine use in preterm babies because they:

- Are immediately available when needed and are suitable for most babies;

- Help to minimise prescribing errors and clinical variation;

- Can improve compliance with national recommendations on quality control of parenteral nutrition manufacturing, dispensing, prescribing and administration;

- Have lower acquisition costs25.

Individualised bags are not immediately available on a neonatal unit and are more complex to prescribe. Without good evidence to support the use of individualised bags, NICE recommends that the additional complexity and cost is not justified. Individualised parenteral nutrition may be needed for babies with more complex needs; for example, babies with a fluid imbalance25.

Enteral nutrition

Pharmacists are not usually involved with management of enteral feeding in preterm infants (e.g. in terms of what feed to use, or the rate that feeds are increased); however, it is important that pharmacists have an awareness of the quantity, volume, composition and route of administration of milk feeds. ESPGHAN recommendations were updated in 2022 to contain information on content of milk, method of administration, growth, supplements and breast milk fortification9.

The British Dietetic Association updated their recommendations in March 2025 on supplementing vitamins and iron in preterm and small for gestational age infants27. The dosing recommendations for multivitamin supplementation can vary depending on the infant’s weight, gestational age and type of milk being administered (fortified breast milk, unfortified breast milk, preterm formula or term formula). The BDA recommend using Abidec as a first-line agent; they do not recommend Dalivit as a direct interchangeable product, as it contains a much higher vitamin A content27.

The BDA dosing recommendations for iron supplementation also vary depending on weight, gestational age and type of milk being administered. Pharmacists should take extra care if patients need to switch to alternative oral iron supplements (for example, due to product shortages) as the amount of elemental iron in each preparation varies — sodium feredetate liquid preparations contain 5.5mg elemental iron in 1mL, whereas ferrous fumarate liquid preparations contain 9mg elemental iron in 1mL27.

A brief summary of the BDA recommendations can be seen in Table 5; see full guideline for further information27.

Pharmacists are often involved in supplying these vitamins, iron preparations and minerals, both while the neonate is in hospital and on discharge. Pharmacists are frequently consulted to provide advice when there are concerns about product licensing; for example, there have been issues with severe hypercalcaemia following vitamin D intoxication in infants given unlicensed food supplements28,29.

Necrotising enterocolitis

The most common gastrointestinal complication in preterm neonates is necrotising enterocolitis (NEC)30. NEC is a serious illness in which tissues in the intestine become inflamed and start to die. This can lead to the development of a perforation, allowing the contents of the intestine to leak into the abdomen, which can lead to a life-threatening infection31. NEC usually presents with the following symptoms:

- An intolerance to feeds;

- High volumes of gastric aspirates;

- Bloody stools and a distended abdomen30.

Incidence worldwide varies between 0.3–2.4 infants per 1,000 live births. Nearly 70% of these cases occur in premature infants born before 36 weeks gestation. NEC affects 2–5% of all premature infants and is responsible for nearly 8% of all NICU admissions. Overall, mortality ranges from 10–50%; however, in the most severe cases, involving perforation, peritonitis and sepsis, mortality approaches 100%30.

A 2017 study published by Battersby et al. reviewed NEC incidence rates in England32. Between 2012 and 2013, there were 531 cases of necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) — 0.4% of all admissions (n=118 073). Total number of deaths owing to severe NEC was 247 (46.5% of NEC cases). Severe NEC in preterm infants (<32 weeks GA) was seen in 462 cases (3.2% patients) and mortality in preterm infants with severe NEC resulted in 222 deaths (48.1%)32.

Medical treatment for NEC involves stopping oral feeds and switching to IV feeding via parenteral nutrition, and the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics (to cover aerobic and anaerobic organisms)33. Circulatory support (e.g. inotropes) may be needed if the baby deteriorates quickly and goes into septic shock34. Surgical management of NEC is sometimes necessary to remove necrosed sections of the bowel35. Possible malabsorption may become a long-term complication if surgery is required and bowel resection is extensive36.

Preventing NEC and its associated complications is an important goal in neonatal care settings. Several clinical strategies have been recommended, including feeding with enteral breast milk. Breast milk has been robustly demonstrated to reduce the risk of NEC compared with formula milk37. Donor milk has a similar, albeit smaller, effect38.

Other strategies to prevent NEC include restricting the use of antibiotics, standardising feeding protocols and supplementation with probiotics39.

A 2022 online survey that was circulated to all UK neonatal units concluded that more than 40% routinely administer probiotics, with variability in the product used. With increased probiotic usage in recent years, there is a need to establish whether this translates to improved clinical outcomes40. In 2023, results from a Cochrane review, involving the outcomes of more than 11,000 infants, showed that the evidence for whether probiotics can prevent NEC in very-low birth weight infants was low to moderate; further large scale, high quality trials are needed41.

A retrospective cohort published in March 2025 evaluated the effectiveness and risks of probiotics in more than 30,000 infants born before 34 weeks’ gestation and with a birth weight of less than 1,000g42. The use of probiotics was associated with a decreased mortality with limited effects on NEC and late-onset sepsis42.

European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition guidance recommends probiotic preparations containing either Lactobacillus rhamnosus or a combination of Bifidobacterium infantis, Bifidobacterium lactis and Streptococcus thermophiles43. Since these are not licensed medications, pharmacists may be asked to examine the evidence for their use for inclusion in hospital formularies, or asked to approve their use from a quality assurance perspective.

Pharmacists should consult systematic reviews and meta-analyses (e.g. Cochrane reviews) that evaluate probiotic efficacy in reducing NEC risk and they should follow local, national and international guidelines, such as those from ESPGHAN43. Not all probiotic strains are equally effective and recommendations may vary.

Probiotics are not licensed as medicines in the UK; they are regulated as food supplements, meaning quality can vary. Products should be chosen from trusted, high-quality manufacturers that provide:

- Good manufacturing practice (GMP) certification;

- Clear labelling of strain, colony-forming units (CFUs) and expiration dates;

- Microbiological purity and safety testing (absence of contaminants)44.

Parents and neonatal staff should be educated on probiotic use, risks and benefits. Correct storage and administration of probiotics needs to be ensured, as they may require refrigeration or specific handling45.

Best practice points

By considering the following points, pharmacists can contribute to the prevention of NEC and support the nutritional management of preterm infants:

Premature infants’ GI challenges:

- Preterm infants have an immature gastrointestinal system, leading to difficulties in nutrient absorption and digestion;

- NEC is a major concern, with preterm infants being especially vulnerable.

Pharmacists’ role in nutritional support:

- PN is essential for many preterm infants until enteral feeding is tolerated.

- Pharmacists play a vital role in preparing and monitoring PN solutions, ensuring they meet the infant’s evolving nutritional needs (e.g. energy, protein and micronutrients).

Probiotics for NEC prevention:

- Probiotics have shown promise in reducing NEC risk, but the evidence is variable (low to moderate quality).

- Probiotics are not licensed medications in the UK, but are regulated as food supplements.

- This article was updated on 4 April 2025 to reflect updated guidance from the British Dietetic Association

- 1.Hu X, Liang H, Li F, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis: current understanding of the prevention and management. Pediatr Surg Int. 2024;40(1). doi:10.1007/s00383-023-05619-3

- 2.Indrio F, Neu J, Pettoello-Mantovani M, et al. Development of the Gastrointestinal Tract in Newborns as a Challenge for an Appropriate Nutrition: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2022;14(7):1405. doi:10.3390/nu14071405

- 3.Eichenwald EC, Cummings JJ, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux in Preterm Infants. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1). doi:10.1542/peds.2018-1061

- 4.Jenkinson A, Aladangady N, Wellmann S, et al. Pancreatic Insufficiency, Digestive Enzyme Supplementation, and Postnatal Growth in Preterm Babies. Neonatology. 2024;121(3):283-287. doi:10.1159/000535964

- 5.Lopez CM, Weller JH, Sodhi CP, Hackam DJ. Evidence-Based Approaches to Minimize the Risk of Developing Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Premature Infants. Curr Treat Options Peds. 2022;8(3):278-294. doi:10.1007/s40746-022-00252-z

- 6.Colarelli AM, MD, Barbian ME, MD, Denning PW, MD. Prevention Strategies and Management of Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Curr Treat Options Peds. 2024;10(3):126-146. doi:10.1007/s40746-024-00297-2

- 7.Rodriguez S, de la Cruz D, Neu J. Nutrition strategies to prevent short-term adverse outcomes in preterm neonates. BMJNPH. 2024;8(Suppl 1):s3-s10. doi:10.1136/bmjnph-2023-000801

- 8.Bronsky J, Campoy C, Braegger C, et al. ESPGHAN/ESPEN/ESPR/CSPEN guidelines on pediatric parenteral nutrition: Vitamins. Clinical Nutrition. 2018;37(6):2366-2378. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2018.06.951

- 9.Embleton ND, Jennifer Moltu S, Lapillonne A, et al. Enteral Nutrition in Preterm Infants (2022): A Position Paper From the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition and Invited Experts. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition. 2022;76(2):248-268. doi:10.1097/mpg.0000000000003642

- 10.Rigo J, Senterre J. Nutritional needs of premature infants: Current Issues. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2006;149(5):S80-S88. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.06.057

- 11.Fusch G, Fink NH, Rochow N, Fusch C. Fatty acids from nutrition sources for preterm infants and their effect on plasma fatty acid profiles. Mol Cell Pediatr. 2024;11(1). doi:10.1186/s40348-024-00183-9

- 12.Mihatsch W, Fewtrell M, Goulet O, et al. ESPGHAN/ESPEN/ESPR/CSPEN guidelines on pediatric parenteral nutrition: Calcium, phosphorus and magnesium. Clinical Nutrition. 2018;37(6):2360-2365. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2018.06.950

- 13.Moltu SJ, Lapillonne A, Iacobelli S. Parenteral Nutrition in Premature Infants. Textbook of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Published online November 25, 2021:87-101. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-80068-0_7

- 14.Milner Y, Stagg W, McElroy H. AB017. Optimising the delivery of parenteral nutrition in newborn care. Pediatr Med. 2020;3:AB017-AB017. doi:10.21037/pm.2020.ab017

- 15.Young L, Oddie SJ, McGuire W. Delayed introduction of progressive enteral feeds to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022;2022(1). doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001970.pub6

- 16.Leaf A, Dorling J, Kempley S, et al. Early or Delayed Enteral Feeding for Preterm Growth-Restricted Infants: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):e1260-e1268. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2379

- 17.Barrington K, El-Khuffash A, Dempsey E. Intervention and Outcome for Neonatal Hypotension. Clinics in Perinatology. 2020;47(3):563-574. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2020.05.011

- 18.Rios DR, Bhattacharya S, Levy PT, McNamara PJ. Circulatory Insufficiency and Hypotension Related to the Ductus Arteriosus in Neonates. Front Pediatr. 2018;6. doi:10.3389/fped.2018.00062

- 19.Cresi F, Maggiora E, et al. Enteral Nutrition Tolerance And REspiratory Support (ENTARES) Study in preterm infants: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20(1). doi:10.1186/s13063-018-3119-0

- 20.Mizuno K, Ueda A. The maturation and coordination of sucking, swallowing, and respiration in preterm infants. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2003;142(1):36-40. doi:10.1067/mpd.2003.mpd0312

- 21.Miller CK. Aspiration and Swallowing Dysfunction in Pediatric Patients. ICAN: Infant, Child, & Adolescent Nutrition. 2011;3(6):336-343. doi:10.1177/1941406411423967

- 22.Oddie SJ, Young L, McGuire W. Slow advancement of enteral feed volumes to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021;2021(8). doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001241.pub8

- 23.Neu J. Gastrointestinal development and meeting the nutritional needs of premature infants. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;85(2):629S-634S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/85.2.629s

- 24.Brune KD, Donn SM. Enteral Feeding of the Preterm Infant. NeoReviews. 2018;19(11):e645-e653. doi:10.1542/neo.19-11-e645

- 25.Overview: neonatal parenteral nutrition: guidance. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020. Accessed March 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng154

- 26.Wilkinson E, Cunningham H, McDonald C, Gite R. Basic principles of parenteral nutrition for paediatrics and term neonates. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. Published online February 17, 2025:edpract-2024-327715. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2024-327715

- 27.Neonatal Dietitians Group (NDiG). The routine supplementation of vitamins and iron and the management of zinc deficiency in preterm and small for gestational age infants. British Dietetic Association. 2025. Accessed April 2025. https://www.bda.uk.com/static/f2a8b727-a487-4223-bc83ba8c62a53874/NDiG-Vit-iron-zinc-March-2025-FINAL-V15.pdf

- 28.Gérard AO, Fresse A, Gast M, et al. Case Report: Severe Hypercalcemia Following Vitamin D Intoxication in an Infant, the Underestimated Danger of Dietary Supplements. Front Pediatr. 2022;10. doi:10.3389/fped.2022.816965

- 29.Pizzini C, Ossato A, Realdon N, Tessari R. Case Report: Nephrocalcinosis in an infant due to vitamin-D food supplement overdose. Front Pediatr. 2024;12. doi:10.3389/fped.2024.1485814

- 30.Ginglen J, Butki N. Necrotizing Enterocolitis. StatPearls. 2024. Accessed March 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513357

- 31.Sylvester KG, Liu GY, Albanese CT. Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Pediatric Surgery. Published online 2012:1187-1207. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-07255-7.00094-5

- 32.Battersby C, Longford N, Mandalia S, Costeloe K, Modi N. Incidence and enteral feed antecedents of severe neonatal necrotising enterocolitis across neonatal networks in England, 2012–13: a whole-population surveillance study. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2017;2(1):43-51. doi:10.1016/s2468-1253(16)30117-0

- 33.Lee JS, Polin RA. Treatment and prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis. Seminars in Neonatology. 2003;8(6):449-459. doi:10.1016/s1084-2756(03)00123-4

- 34.Wynn JL, Wong HR. Pathophysiology and Treatment of Septic Shock in Neonates. Clinics in Perinatology. 2010;37(2):439-479. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2010.04.002

- 35.Bethell GS, Knight M, Hall NJ. Surgical necrotizing enterocolitis: Association between surgical indication, timing, and outcomes. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2021;56(10):1785-1790. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2021.04.028

- 36.Marroquín IE, Guerrero MFI, et al. Necrotizing Enterocolitis: A Literature Review of Basic Concepts, Diagnosis and Treatment Options. IJMSCRS. 2024;04(12). doi:10.47191/ijmscrs/v4-i12-52

- 37.Bode L. Human Milk Oligosaccharides in the Prevention of Necrotizing Enterocolitis: A Journey From in vitro and in vivo Models to Mother-Infant Cohort Studies. Front Pediatr. 2018;6. doi:10.3389/fped.2018.00385

- 38.McGuire W. Donor human milk versus formula for preventing necrotising enterocolitis in preterm infants: systematic review. Archives of Disease in Childhood – Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2003;88(1):11F – 14. doi:10.1136/fn.88.1.f11

- 39.Jin YT, Duan Y, Deng XK, Lin J. Prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants – an updated review. WJCP. 2019;8(2):23-32. doi:10.5409/wjcp.v8.i2.23

- 40.Patel N, Evans K, et al. How frequent is routine use of probiotics in UK neonatal units? bmjpo. 2023;7(1):e002012. doi:10.1136/bmjpo-2023-002012

- 41.Sharif S, Meader N, Oddie SJ, Rojas-Reyes MX, McGuire W. Probiotics to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very preterm or very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023;2023(7). doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005496.pub6

- 42.Alshaikh BN, Ting J, Lee S, et al. Effectiveness and Risks of Probiotics in Preterm Infants. Pediatrics. 2025;155(3). doi:10.1542/peds.2024-069102

- 43.van den Akker CHP, van Goudoever JB, Shamir R, et al. Probiotics and Preterm Infants. J pediatr gastroenterol nutr. 2020;70(5):664-680. doi:10.1097/mpg.0000000000002655

- 44.Ahire JJ, Rohilla A, Kumar V, Tiwari A. Quality Management of Probiotics: Ensuring Safety and Maximizing Health Benefits. Curr Microbiol. 2023;81(1). doi:10.1007/s00284-023-03526-3

- 45.Probiotic use for neonates in North West London Perinatal Network neonatal units. London Neonatal Operational Delivery Network. 2021. Accessed March 2025. https://londonneonatalnetwork.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/NWLPODN-Probiotic-use-for-neonates-V1.0.pdf