Mclean/Shutterstock.com

“Ten-fold medication errors in children are a problem everyone fears,” says consultant paediatric nephrologist Yincent Tse.

“Everyone’s seen it happen before, but we’ve never really measured it or taken a wide view of it. We’ve never really had good data,” adds Tse, who is lead for patient safety and quality improvement on the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) Quality Improvement Committee and joint RCPCH/Neonatal & Paediatric Pharmacists Group Medicines Committee.

Medication errors have received rising political and media attention in recent years, with a global World Health Organization initiative to reduce avoidable medication-related harm, and subsequently commissioned studies estimating an annual incidence of 237 million medication errors in the UK[1–3]. However, these initiatives hold an adult-centric view, with paediatrics not/ largely featured. In fact, paediatrics has previously been called ‘an evidence-based desert’ and knowledge gaps still remain. But recent developments are aiming to change this[4,5].

A national investigation into weight-based medication errors in children was launched in January 2021 by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (HSIB), triggered by a reported case of an unintentional ten-fold overdose in a four-year-old child[6]. Although the clinician had correctly interpreted the dose from the guiding formularies, the prescribing pathway led to the administration of the ten-fold overdose on five separate occasions before it was identified. Using this as a reference event around which to build the investigation, HSIB aims to examine the various angles that lead to medication errors.

We’re not looking at just the prescribing, but at the dispensing and the administration as well

Helen Jones, HSIB national investigator

“We’re not looking at just the prescribing, but at the dispensing and the administration as well — and as part of that, we’re looking at different facets of the system: at broader issues such as multidisciplinary team working; communication; the role of the second checker in medicines administration,” explains Helen Jones, an HSIB national investigator. It is hoped that the findings of the investigation will advance what is currently known about paediatric medication errors.

Added layers of complexity

What is already widely accepted as common knowledge is the unique complexity of paediatric medicines.

“There are more calculation steps when prescribing for kids than there are for adults,” explains Daniel Hawcutt, a consultant paediatric clinical pharmacologist at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital and senior lecturer in paediatric clinical pharmacology, women’s and children’s health at the University of Liverpool.

Dosing is often weight-scaled to account for extremes of size differences, between, say, 5kg neonates and 50kg adolescents. To enable this dosing flexibility, paediatric drugs are typically liquids — but dose guidance is given in milligrams or units per milligram.

“So there’s also an additional conversion of how many milligrams have been prescribed to how many millilitres need to be given in liquid formulation,” Hawcutt adds. Sometimes, even a further calculation is needed to account for the concentration of the specific drug product available at that hospital or pharmacy.

Then there is the use of drugs off-licence, which is particularly common in paediatrics since most drugs have been made for, and researched in, adults. In 2007, the law changed in the UK to require development of age-appropriate drug formulations for new drugs.

“So, any new drug that’s being developed now has to be tested for safety and efficacy in children; you have to do a paediatric formulation,” says Hannah Batchelor, a professor in pharmaceutics at the University of Strathclyde, who is researching the development of age-appropriate medicines for children.

“But it won’t be done retrospectively. The new drugs coming out are all cancer agents and things that are rarely used, so the commonly used drugs, people are still struggling on with.”

Each layer of complexity offers another opportunity for errors. Furthermore, such bespoke, individualised dosing means “you can’t have that sort of intuitive feel of what the right dose should be that you would have in adult medicine,” explains Hawcutt.

In adults there’s only one dose — you know that paracetamol is 1g or ibuprofen is 400mg, but that doesn’t work in paediatrics

Daniel Hawcutt, consultant paediatric clinical pharmacologist at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital

“In adults there’s only one dose — you know that paracetamol is 1g or ibuprofen is 400mg, but that doesn’t work in paediatrics.”

Working with such diverse doses undermines the usual warning flags raised when administering a ten-fold overdose or underdose, further frustrating maintenance of adequate checking procedures.

These accounts are anecdotal; however, recent studies in secondary care are beginning to evidence them.

Evidence of error

Working in collaboration with David Tuthill, RCPCH officer for Wales and chair of the British National Formulary for Children, Tse used the Welsh Paediatric Surveillance Unit error reporting system to conduct a two-year population study in paediatric ten-fold medication errors — a world first[7].

The results describe an annual incidence of 4.6 errors per 100,000 children in the UK, of which almost one quarter result in moderate or severe harm.

“If we extrapolate to the rest of the UK, we estimate we’ll probably get about 250 definite cases a year in the whole of the UK,” Tse says, explaining that he and Tuthill are now looking to expand the study across Great Britain using the British Paediatric Surveillance Unit system for confirmation.

The data from the Welsh study offers valuable insight. “We had 50 cases overall: 20 actual cases where medicines reached a child, and 30 near-misses.

Of the 50 cases, there were so many medicines involved

Yincent Tse, consultant paediatric nephrologist

“Of the 50 cases, there were so many medicines involved: you can’t say, ‘Oh, it’s just paracetamol and morphine’. I think we had 37 different medicines and 43 different permutations of medicine, route and form,” reveals Tse.

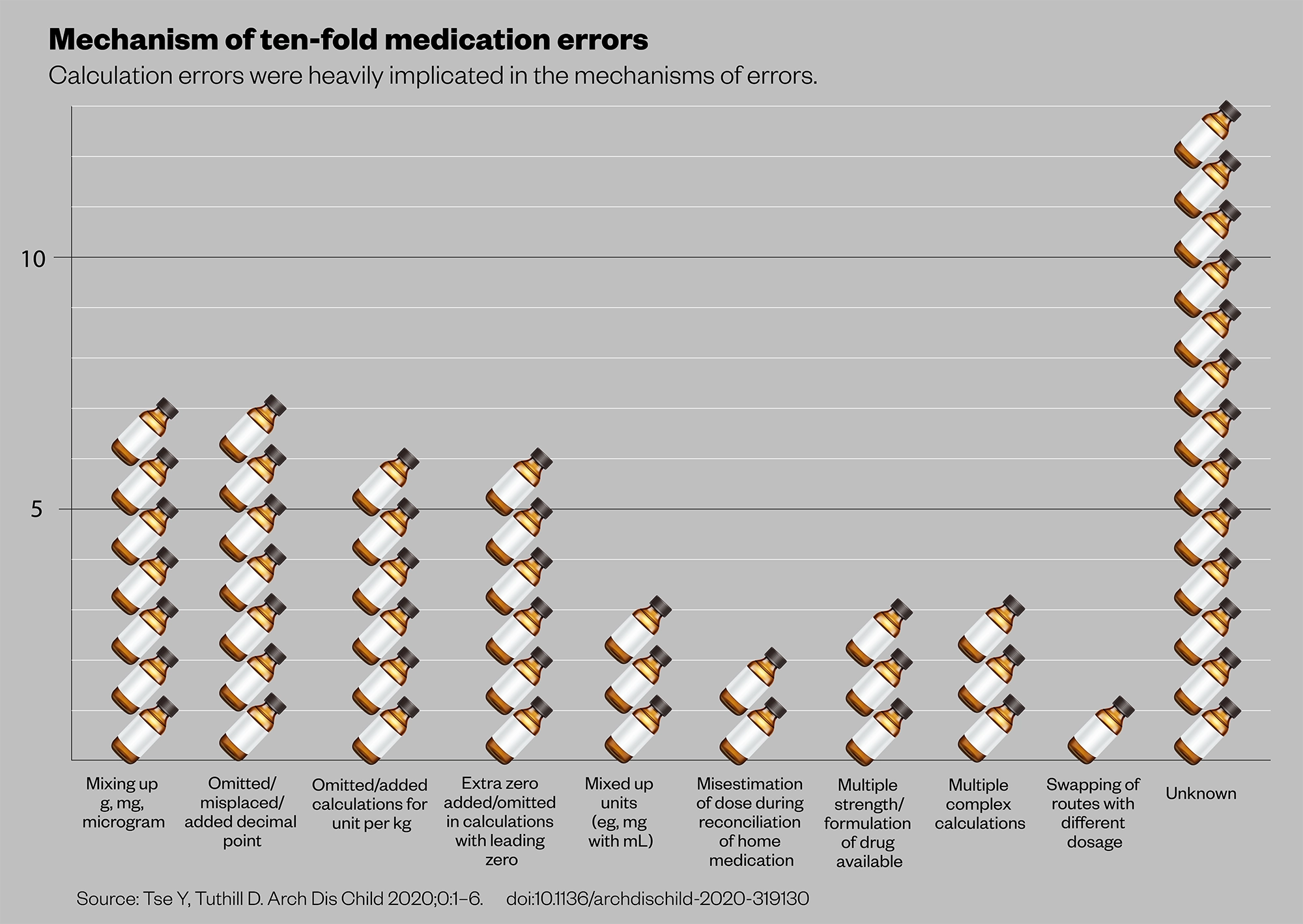

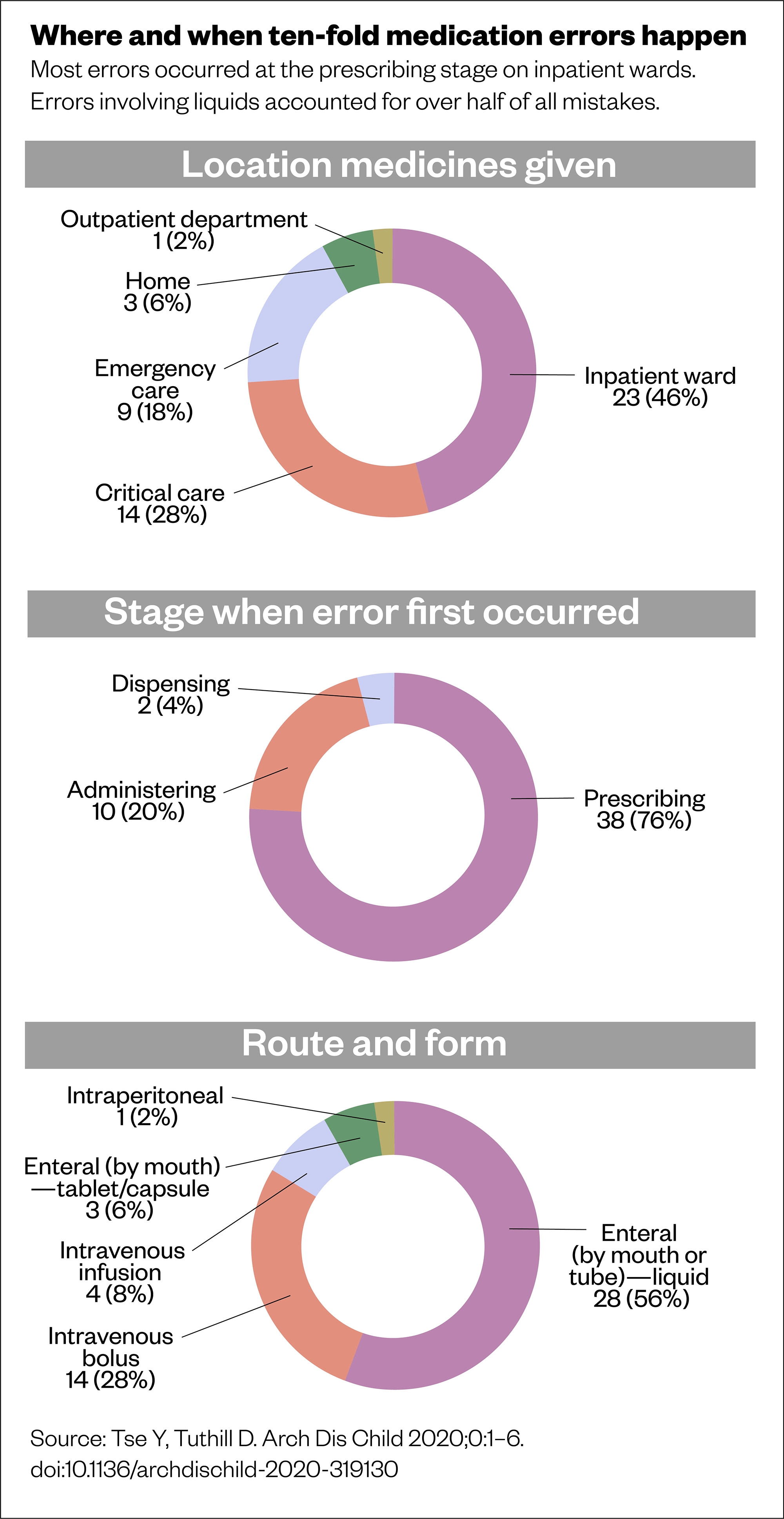

This suggests the issue of ten-fold medication errors is generalised among the paediatric population. Further analysis into the characteristics of these cases supports anecdotal findings about the potential for errors when calculating doses for children. For instance, although enteral administration (by mouth or tube) made up 31 of the total 50 error cases, definite errors within this category were only observed with liquids, not tablets or capsules. Similarly, intravenous bolus doses and infusion pump calculations were subject to error. Looking at the root causes, calculations were heavily implicated, including unit mix-ups, missing or erroneously adding weight dose adjustments, incorrect conversions for different concentrations and even decimal point misplacements (see Figures 1 and 2)[7].

Figure 1

Figure 2

A team based at Imperial College London took a completely different approach, instead outfitting doctors and nurses with cameras and running paediatric emergency simulations in an observational study[8].“We could really see how the team worked; what they were doing; the buttons they were pressing; and what they were mumbling to themselves and saying to each other as they worked through the process,” Nicholas Appelbaum, lead author of the study, describes.

Micro-analysing the footage, the team were able to pinpoint exactly what had gone wrong, and map this against the cognitive journey a clinical team follows from prescribing through to administration. Their findings were similar to the root causes identified in Tse’s study, with calculations and conversions at fault — but interestingly, error hotspots were also identified when moving between digital interfaces, such as correctly interpreting the dose from formularies or having to switch between different resources. In particular, guidelines for injectables and complex dose tables proved difficult to read in time-pressurised situations[8,9].

It is worth noting that medication errors are thought to be substantially under-reported. In Appelbaum’s simulation study, only 2 of 52 (4%) errors were retrospectively identified by the clinicians[8]. Moving forward in this area will require a reassessment of error reporting methods, and addressing the stigma surrounding errors in clinical culture, to accurately monitor any improvements.

Going digital

One much-hyped solution is increasing digitisation, from electronic prescribing and medicines administrations systems (EPMAs) or clinical decision support (CDS), to electronic patient records. These initiatives are receiving governmental investment to improve medication errors.

However, these electronic solutions are evolving and remain under scrutiny. Some research indicates that although EPMAs reduce errors associated with legibility and transcription, they shift rather than eliminate the error burden, allowing for new errors, such as accidentally selecting the wrong option from a drop-down list[10]. EPMA use forms an element of the ongoing HSIB national investigation, with an EPMA system implicated in its reference case[6].

“The doctor knew that the child’s weight was 15.2kg, so the intention was to prescribe 1,500 units of dalteparin twice per day, which was the calculated dose,” Jones explains.

“However, when he went into the system, because of the way the information was available to him there, he ended up inadvertently prescribing 15,000 units.” The investigation is therefore also seeking to illuminate the risks that EPMA poses to weight-based paediatric prescribing and administration. An interim bulletin from the HSIB, published on 18 March 2021, highlighted that it would be beneficial for trusts at which adult and paediatric prescribing is supported through the same EPMA system to ensure they have adequately risk-assessed the way the system supports the calculation of doses, to make sure that adult doses do not require manipulation for paediatric patients.

One problem associated with the rollout of electronic systems is standardisation.

There is not ‘one’ single electronic prescribing system that is used by hospitals

Andy Fox, consultant pharmacist in medicines safety

“There is not ‘one’ single electronic prescribing system that is used by hospitals,” Andy Fox, consultant pharmacist in medicines safety, states. And even within one hospital, different systems could be in use between adult and paediatric wards. Additionally, each system is configured separately by individual hospitals to match local guidance and information, such as syringe sizes and available drug preparations — meaning they require continual updates against national guidance, which places a resource burden on pharmacy teams.

The impact the lack of standardisation has on error-making and patient harm is not fully understood, but Fox points to a study his team ran in 2019, where, across 7 EP systems used in 22 NHS hospital trusts, 90.7% of incorrect medicines orders were possible to prescribe and were not detected by the systems’ pre-programmed alerts[11].

“It clearly shows that different systems have different abilities to identify potential errors to the prescriber. Even the same EP system in different hospitals has variations in the levels of CDS presented to the prescriber, because the individual hospitals will have implemented it and optimised it at a local level.”

Thorough research notwithstanding, it is clear EPMA is an area long overdue for advancement.

Appelbaum, who also has an interest in digital solutions to medication errors, highlights the paradox exposed by EPMA’s placement in modern healthcare: “How can a patient — child or adult — be wheeled out of the neuro-endovascular laboratory, where we’ve coiled an aneurysm in a deep branch of the middle cerebral artery using 3D reconstructed image guidance — advanced stuff — and then, wheeled down the corridor to the ward where we are going to use an EPMA with a very high chance of a medication error coming about? If they’re a child, a significantly higher chance.”

Development of next-generation EPMA could change the landscape of paediatric medications errors yet again.

A solid solution

Alternatively, improvements could be gained from moving away from liquid presentations. Tse sees many patients taking a vast array of medicines, predominantly liquids.

“The parents come with lots of bottles clonking around, and many of them, especially the ones that are specially made, have quite short expiry dates,” he explains.

“So, from the patient’s perspective, they’re traipsing around pharmacies finding these medicines, and, if they run out on a Saturday, it’s a huge problem. It’s not like in adults where you can get three months’ [supply] at a time.”

Seeing a huge benefit for patients who could switch from liquids to tablets, Tse’s team has developed resources to teach children to swallow tablets[12,13]. There can be a default assumption that swallowing tablets is too difficult for children, especially younger ones, but as Tse finds: “In many cases, we’d say to a child, ‘Can you swallow a sweet?’ and they’d say ‘Yes’. So, we’d say ‘Try this’ and they’d do it.” Fighting this assumption could open up a wider pool of existing drug products to paediatrics.

Recent research has sought to determine weight-based dose bands as a workaround for highly individualised dose calculations; these would also make the use of solid dosage forms more achievable[14].

Pharmaceutical developments are also under way to design age-appropriate formulations.

“One of the things that’s becoming popular in research is a dispersible tablet, where you put the tablet on a spoon, add some water, and it becomes a liquid,” Batchelor explains.

In addition, mini-tablets — which are of a more manageable size for small children and offer the all-important increased flexibility in dose-scaling — is another area that is receiving pharmaceutical attention.

One simple solution echoed by many is increasing involvement of paediatric pharmacists in all prescribing pathways that involve children[7,8].

It is apparent, however, that not enough is yet known about paediatric medication errors to pinpoint a clear solution. It is appropriate then, says Hawcutt, that “given it’s a problem that’s been around for an awful long time, it’s finally getting its turn in the sun”.

- 1NHS England. The Medicines Safety Improvement Programme. NHS. https://www.england.nhs.uk/patient-safety/national-medicines-safety-programme/ (accessed 6 Apr 2021).

- 2World Health Organization. Medication Without Harm – Global Patient Safety Challenge on Medication Safety. World Health Organization. 2017.https://www.who.int/patientsafety/medication-safety/en/ (accessed 6 Apr 2021).

- 3Elliott R, Camacho E, Campbell F, et al. Prevalence and Economic Burden of Medication Errors in The NHS in England. Rapid evidence synthesis and economic analysis of the prevalence and burden of medication error in the UK. Policy Research Unit in Economic Evaluation of Health and Care Interventions (EEPRU), Universities of Sheffield and York 2018.

- 4Sutcliffe AG, Wong ICK. Rational prescribing for children. BMJ 2006;332:1464–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7556.1464

- 5Corrick F, Conroy S, Sammons H, et al. Paediatric Rational Prescribing: A Systematic Review of Assessment Tools. IJERPH 2020;17:1473. doi:10.3390/ijerph17051473

- 6Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch . Weight-based medication errors in children. Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch . 2021.https://www.hsib.org.uk/investigations-cases/weight-based-medication-errors-children/ (accessed Apr 2021).

- 7Tse Y, Tuthill D. Incidence of paediatric 10-fold medication errors in Wales. Arch Dis Child 2020;:archdischild-2020-319130. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2020-319130

- 8Appelbaum N, Clarke J, Feather C, et al. Medication errors during simulated paediatric resuscitations: a prospective, observational human reliability analysis. BMJ Open 2019;9:e032686. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032686

- 9Appelbaum N, Clarke J, Feather C, et al. Medication errors during simulated paediatric resuscitations: a prospective, observational human reliability analysis. Helix Centre. 2019.https://helixcentre.com/_content-img/touchdose/eposter.pdf (accessed Apr 2021).

- 10Caldwell NA, Power B. The pros and cons of electronic prescribing for children. Arch Dis Child 2011;97:124–8. doi:10.1136/adc.2010.204446

- 11Fox A, Portlock J, Brown D. Electronic prescribing in paediatric secondary care: are harmful errors prevented? Arch Dis Child 2019;104:895–9. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2019-316859

- 12Tse Y, Vasey N, Dua D, et al. The KidzMed project: teaching children to swallow tablet medication. Arch Dis Child 2020;105:1105–7. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2019-317512

- 13E-Learning for Healthcare . KidMedz: A resource to teach children how to swallow pills. KidMedz. 2021.https://www.e-lfh.org.uk/programmes/kidzmed/ (accessed Apr 2021).

- 14Rashed AN, Tomlin S. Establishing dose bands for commonly prescribed oral medications for children in the UK: Results of a Delphi study. Br J Clin Pharmacol Published Online First: 11 January 2021. doi:10.1111/bcp.14698