Mclean/Shutterstock.com

In October 2020, NHS England and NHS Improvement (NHSE&I) approved an ambitious new strategy to become the world’s first national health service to agree net zero emissions commitments as part of the global effort to tackle climate change.

To hold itself accountable, it set two main targets: to become net zero by the year 2040 for emissions it controls directly, referred to as the NHS Carbon Footprint, and to achieve net zero by 2045 for emissions it influences but does not directly control, referred to as the NHS Carbon Footprint Plus.

Of all the emissions generated by the NHS, medicines account for 25%, and there is a significant focus on two groups — anaesthetic gases (2% of emissions) and inhalers (3% of emissions) — where emissions occur at the ‘point of use’[1].

Efforts to reduce emissions from anaesthetic gases are already taking effect. Minutes from a public NHSE&I meeting, held in September 2021, confirmed that the NHS had exceeded its target to reduce the use of the anaesthetic desflurane to 10% by 2021/2022, with the use of desflurane by NHS trusts now lower than 10% of all volatile gases by volume, at an average of 9.5%.

However, measures to reduce emissions from inhalers have not been welcomed so warmly.

In September 2021, a document published by NHSE&I, detailing plans for primary care networks (PCNs) for 2021/2022 and 2022/2023, set out a suite of incentivised targets to support improved respiratory care and health outcomes for asthma patients, as well as ambitions to reduce avoidable carbon emissions by encouraging the choice of lower carbon inhaler alternatives, where clinically appropriate (see Box 1)[2].

But it is one specific PCN incentive, adopted in October 2021, that has generated heated debate among respiratory specialists, which encourages switching patients from metered-dose inhalers (MDIs) to dry powder inhalers (DPIs) and soft mist inhalers (SMIs).

“Our aim is that, in line with best practice in other European countries, by 2023/2024, only 25% of non-salbutamol inhalers prescribed will be MDI inhalers,” the document states.

The reasoning it gives is that, in general, DPIs and SMIs offer a low-carbon alternative to MDIs.

Dry powder inhalers aren’t as green as we think they are

Garry McDonald, respiratory pharmacist consultant

But respiratory experts argue that, when considering the whole life cycle of the inhaler and the use of inhalers by patients, this is not always the case.

“The ‘NHS long term plan’ simply stated [switching to] a lower carbon inhaler [to deliver a 4% reduction in the carbon footprint of health and social care],” explains Garry McDonald, a respiratory pharmacist consultant who works across the UK, “but that message has been diluted and misheard to mean that it has to be a DPI; dry powders aren’t as green as we think they are.”

Jane Scullion, a respiratory nurse consultant at University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, has concerns about the impact the incentives could have on patient care.

“I’m always against anything that incentivises drug switches … we’ve seen it before, when the generics started coming out for inhalers, where suddenly people were switched on to a different inhaler and [then] they would come back because they didn’t like it so they didn’t use it, or they hadn’t been taught how to use it.”

“Sometimes, these targets become a target to achieve and are not done the right way,” agrees Toby Capstick, consultant pharmacist in respiratory medicine at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust.

“It’s reasonable to switch inhalers but it has to be done for the right reasons.”

Box 1: The Primary Care Network incentives

From October 2021:

- Dry powder inhalers (DPIs) and soft mist inhalers (SMIs) offer a low-carbon alternative to metered dose inhalers (MDIs). From October 2021, the NHS’s Investment and Impact Fund (IIF) will reward increased prescribing of DPIs and SMIs where clinically appropriate;

- Salbutamol MDIs are the single biggest source of carbon emissions from NHS medicines prescribing. From October 2021, the IIF will also reward increased prescribing of less carbon intensive salbutamol MDIs.

From 2022/2023:

- The IIF will reward primary care networks (PCNs) for increasing the percentage of asthma patients who are regularly prescribed an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS, or preventative inhaler), where clinically indicated;

- A further incentive will directly reward PCNs for achieving these reductions in avoidable SABA prescribing.

Environmental impact of inhalers

Up until the early 1990s, MDIs contained chloroflurocarbon (CFC) propellants. It was then discovered that they were damaging the atmospheric ozone layer and were consequently phased out on an international level[3]. To replace them, pharmaceutical companies developed CFC-free MDIs, containing hydrofluroalkane (HFA) propellants.

However, this did not solve all of the environmental problems associated with these devices; there is now increasing attention on the environmental impacts of HFAs, which are themselves powerful greenhouse gases[4].

“Most inhalers use HFA134 as a propellant, which has a high global warming impact, and a small number use HFA227, [which has] a very high global warming impact,” explains Capstick.

DPIs do not require a propellant, which is why they are favoured as a low-carbon option; instead, they rely on the patient breathing in quickly to inhale the drug into their lungs. A patient decision aid from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) shows that MDIs have an estimated carbon footprint of 500g carbon dioxide equivalent per dose, compared with 20g for DPIs[5].

However, DPIs too are far from environmentally friendly.

Ethically, what we should be doing is trying to use the devices that are best for the patient

Toby Capstick, consultant pharmacist, respiratory medicine, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

“The trade off with DPIs is that they contain a lot of plastic,” says Capstick.

“And there is some research that shows that DPIs score worse on a lot of other environmental measures in terms of the development, production and end-of-life disposal … [in fact], they score much, much worse than MDIs [in these areas],” explains Capstick.

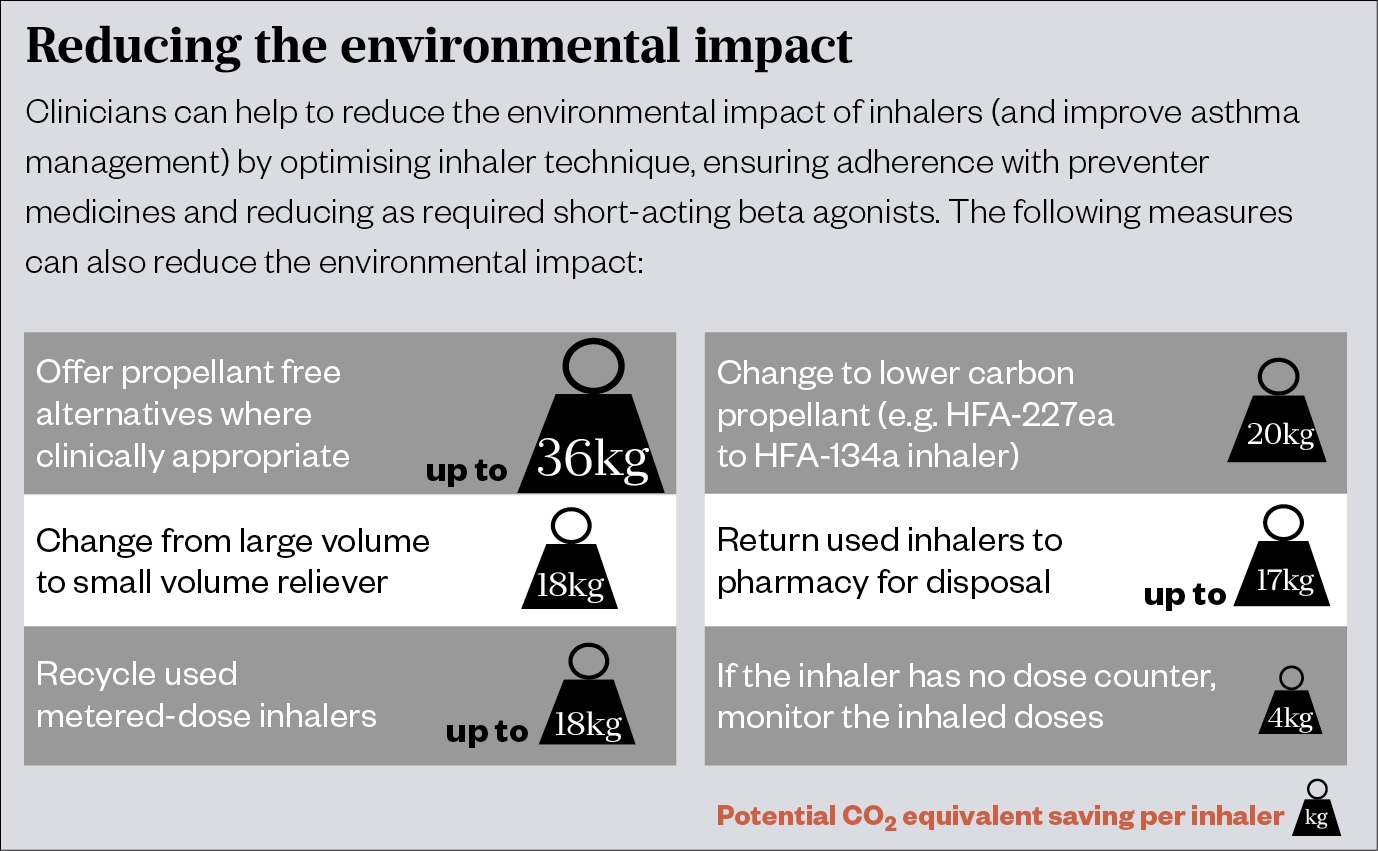

Respiratory experts argue that by focusing on the patient, rather than specific inhalers, the environmental benefits sought by the NHS will still be achieved.

“Ethically, what we should be doing is trying to use the devices that are best for the patient,” says Capstick, adding that the people who are contributing the most to the environmental harm or carbon impact of inhalers are those with poorly controlled disease.

“If you’re poorly controlled, your condition is going to be exacerbated; you’re going to go to your GP, you’re going to go to your hospital, and you’ve got all that carbon impact in terms of car drives, ambulances and everything else involved in that emergency care.”

Focusing on patients

Capstick explains that Leeds Clinical Commissioning Group — where he is based — is the fourth best performing when it comes to the lowest carbon impact of inhalers; despite the fact that they have never had an environmental agenda.

“What we focus on within our guidelines is to get people on devices that they can use first. So, we check: can they breathe in quick and deep, and [can therefore] use a DPI, or can they breathe in slow and steady, and [be better suited to] use an MDI or a soft mist inhaler?”

He likens the mechanics of using an MDI as akin to driving a car around a sharp bend to illustrate the importance of using a ‘slow and steady’ technique.

“With an MDI, the aerosols are coming in around 35–40 miles an hour, and if you breathe in [too] fast, you just accelerate that … you’re spraying it horizontally, it hits the back of your throat and has to do a sharp bend to get into your lungs.”

However, for some patients, switching from an MDI to a DPI can lead to poor disease control because they are unable to generate the deep inspiratory breath required to inhale the drug into their lungs properly.

Scullion explains that, for children, older people and those with cognitive problems or issues with dexterity, an MDI, used with a spacer, is the only appropriate option available. However, she highlights that, even for people who fall outside of these categories, switching them from an MDI to a DPI can be a significant change, particularly if their asthma is well-controlled.

“If it’s a brand-new patient, I have no issue with them being shown the devices and put on the most appropriate that they can use because they’ve never known anything else,” she says, “but some asthmatics may have had [the same type of inhaler] since childhood; that might be 40 odd years of being controlled on your medication and then somebody wants to switch you to something that might not work [for you].”

McDonald summarises: “The best inhaler is the one the patient can use, will use and does use.”

And finding out whether an inhaler is suitable for a patient and that they can use it properly requires a proper assessment.

“Never ask a patient ‘Do you know how to use your inhalers?’, because you know what answer you’re going to get: ‘Of course I do!’

“[Instead] the phrase I always use is ‘Can you show me how you use your inhalers?’”

My biggest fear is that somebody will just do it all by post, and then we’ll have to pick up all the pieces afterwards

Jane Scullion, respiratory nurse consultant, University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust

But, with more than 4.8 million people in England and Wales who have asthma, the vast majority of whom will potentially need their inhaler switching under this incentive, McDonald questions how, realistically, these assessments are going to be carried out[6].

“How are we going to check their inhaler technique? Are we going to call them into the surgery? GPs don’t have time for that. [But] if we’re going to do this properly, that’s what we’re going to have to do — engagement with the patient is key.”

As Scullion highlights, the switching process on its own comes with an environmental cost that needs to be considered.

“There’s a cost of the face-to-face appointment, a cost on the environment of driving there and getting people in; my biggest fear is that somebody will just do it all by post, and then we’ll have to pick up all the pieces afterwards.”

However, when asked about this by The Pharmaceutical Journal, NHS England stuck by their targets. A spokesperson said: “Clinicians are enabling patients to choose greener devices only when it is clinically appropriate for them to do so.

“The incentives for PCNs on inhalers are the product of extensive clinical input and patient engagement.”

Readjusting the focus

Most people do agree on the need for a national inhaler recycling scheme in order to properly dispose of used inhalers. But, unlike the PCN incentives, this still seems a long way off. Responding to a freedom of information request from The Pharmaceutical Journal in August 2021, NHSE&I confirmed that it “did not currently have any plans” for such a scheme (see Box 2).

“I think some of it is difficult because it is contaminated pharmaceutical waste, in some regards,” says Capstick.

“But you do think, all that single use plastic — surely in this day and age we should be able to do something.”

McDonald argues that, to make a real difference to the environment, there is a need to look at the bigger picture. For example, he mentions a new HFA gas “on the horizon”, called HFA152, which is being considered as a candidate to replace HFA134 to reduce the environmental impact, owing to its carbon footprint being ten times lower[3].

“If we throw out metered-dose inhalers, in two to three years when this [new] gas does come in, there’ll be no device to put it into.”

Instead, he says the focus should be on helping patients to use fewer inhalers.

“Right now, nationally, we’re using about eight blue inhalers for every brown; it should be the other way round, we should use around six brown for every blue. If you’re using your blue inhaler more than twice a week, your asthma is not controlled.”

Capstick agrees: “One of the positive things about the PCN agreement is that it does talk about the need to improve respiratory care and health outcomes … I think that’s the primary focus: we need to improve asthma control, if we do that, we’ll reduce SABA [short-acting beta agonist] use and that’s going to have an overwhelming impact on environmental harm.”

Box 2: Can we recycle inhalers in the UK?

In July 2020, it was announced that the ‘Complete the cycle’ programme, run by pharmaceutical firm GSK, was to close at the end of September 2020, after nine years.

At the time, it was thought to be the only scheme of its kind in the UK. GSK said that since 2011, when the scheme began, more than two million inhalers had been recycled and recovered, saving a similar amount of CO2 emissions as that produced by 8,665 cars in one year. The scheme recycled inhalers made by other manufacturers, as well as those made by GSK.

On closing the scheme, a spokesperson for GSK said there needed to be a focus on a wider, joint-working approach across industry, rather than their own standalone approach.

In February 2021, pharmaceutical company, Chiesi, launched the UK’s first postal inhaler recycling scheme.

The aim was that the pilot scheme, ‘Leicestershire take action for inhaler recycling’, would run for 12 months, disposing and recycling empty and unwanted inhalers of any brand or type, with the users sending them via post.

After 12 months it will be assessed for effectiveness and how it can best be rolled out in other areas. However, figures obtained by The Pharmaceutical Journal in July 2021, revealed that of the 227 community pharmacies invited to participate, only 141 community pharmacies had signed up.

Responding to a freedom of information request in August 2021, regarding its plans to establish a national inhaler recycling scheme, NHS England and NHS Improvement (NHE&I) confirmed that it “did not currently have any plans” for such a scheme.

This was despite an NHS-funded national working group being established in 2019 that aims to reduce the climate change impact of asthma inhalers.

In its written response, sent on 18 August 2021, NHE&I said: “Nationally, the recycling of inhalers is enabled through the general contractual obligation for community pharmacies to accept returned medicine waste (including inhalers).

“This ensures medicine waste is disposed of in the safest and most environmentally friendly way.”

NHSE&I added that it was aware of a range of local and manufacturer-led inhaler disposal schemes, which it “encouraged use of across the NHS”.

READ MORE: Blue, brown and now green

- 1Delivering a ‘Net Zero’ National Health Service. NHS 2020. https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/wp-content/uploads/sites/51/2020/10/delivering-a-net-zero-national-health-service.pdf (accessed 13 Oct 2021).

- 2Annex B – Investment and Impact Fund (IIF): 2021/22 and 2022/23. NHS 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/B0828-iii-annex-b-investment-and-impact-fund-21-22-22-23.pdf (accessed 13 Oct 2021).

- 3Panigone S, Sandri F, Ferri R, et al. Environmental impact of inhalers for respiratory diseases: decreasing the carbon footprint while preserving patient-tailored treatment. BMJ Open Resp Res 2020;7:e000571. doi:10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000571

- 4DeWeerdt S. The environmental concerns driving another inhaler makeover. Nature 2020;581:S14–7. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-01377-7

- 5Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80/resources (accessed 13 Oct 2021).

- 6Asthma death toll in England and Wales is the highest this decade. Asthma UK. 2019.https://www.asthma.org.uk/about/media/news/press-release-asthma-death-toll-in-england-and-wales-is-the-highest-this-decade/ (accessed 13 Oct 2021).