Mclean/shutterstock.com

At the start of the millennium, Ken Clare finally faced up to his weight problem.

With a body mass index (BMI) of more than 60, he struggled to do simple things, such as walking or getting dressed, and he anticipated that he would eventually need a wheelchair to get around.

“And if I ended up in a wheelchair, I probably wouldn’t last long, health wise,” he remembers.

Clare was referred by his GP to an NHS weight management clinic, where he received dietary advice and cognitive behavioural therapy, and attended exercise classes. He was also prescribed a drug called Xenical (orlistat; Roche), which works by preventing fat absorption.

However, two years later, nothing seemed to be working and he was faced with his last resort: bariatric surgery.

Defined as a BMI of 30 or greater, the level of obesity is growing in the UK, affecting one-third of adults and putting huge strain on the NHS[1].

Obesity brings with it many complications, including an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus and stroke. Health risks associated with obesity have tragically been highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic, during which obesity has been associated with more severe cases of COVID-19[2,3].

In addition to physical complications, mental anguish and humiliation often hound people with obesity, because they feel they are to blame for their condition. During the peak of his obesity, Clare remembers feeling miserable, depressed and, at times, suicidal.

Despite these dangers, no one had ever talked to Clare about his weight before he enrolled in the weight clinic. Even now, more than 20 years later, and with increased knowledge about the biology of weight regulation, many clinicians feel that beyond advising their overweight patients to eat less and exercise more, there is little they can do.

New treatment options

However, new medicines are beginning to offer some alternative options. In 2020, a weight-loss drug called Saxenda (liraglutide; Novo Nordisk) became available on the NHS in England. Then, in February 2022, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) issued draft guidance recommending Wegovy (semaglutide; Novo Nordisk) for obese adults with at least one weight-related condition[4].

The public health message for people with obesity has been to ‘eat less and move more’ but that hasn’t worked, not for thousands of years

Carel le Roux, obesity physician at University College Dublin

These, and other drugs in the pipeline, could provide alternatives to people who have tried diet and exercise and it has not been effective. They may also help to change people’s attitudes about obesity, from a personal failure to a chronic physiological condition that needs managing.

“The public health message for people with obesity has been to ‘eat less and move more’ but that hasn’t worked, not for thousands of years,” says Carel le Roux, an obesity physician at University College Dublin.

“It’s time we change that message to ‘seek help’ because obesity is a biological disease that needs a biological treatment, whether it is a nutrition treatment or a medication or a surgical treatment.”

Gut–brain connection

The mounting prevalence of obesity in the UK led Public Health England to start the Better Health campaign in 2020 to reach overweight people and guide them to behaviours and services that can help with weight management[5]. Part of this includes the expansion of weight management services.

While a commitment to healthy eating and regular exercise can help many people lose weight, it often falls short for people with obesity. The reasons are complex, but physiology may be blamed in part. When eating, the gut releases multiple hormones that prepare the body for digestion, and that also provide satiety signals to the brain. In obesity, these hormonal responses seem blunted, so people do not receive the normal cues to stop eating.

To make matters worse, the body tends to guard against weight loss.

Just by losing weight alone, this will increase your hunger hormones and decrease your satiety hormones

Philip Newland-Jones, consultant pharmacist and clinical director of the endocrine diabetes service at Southampton General Hospital

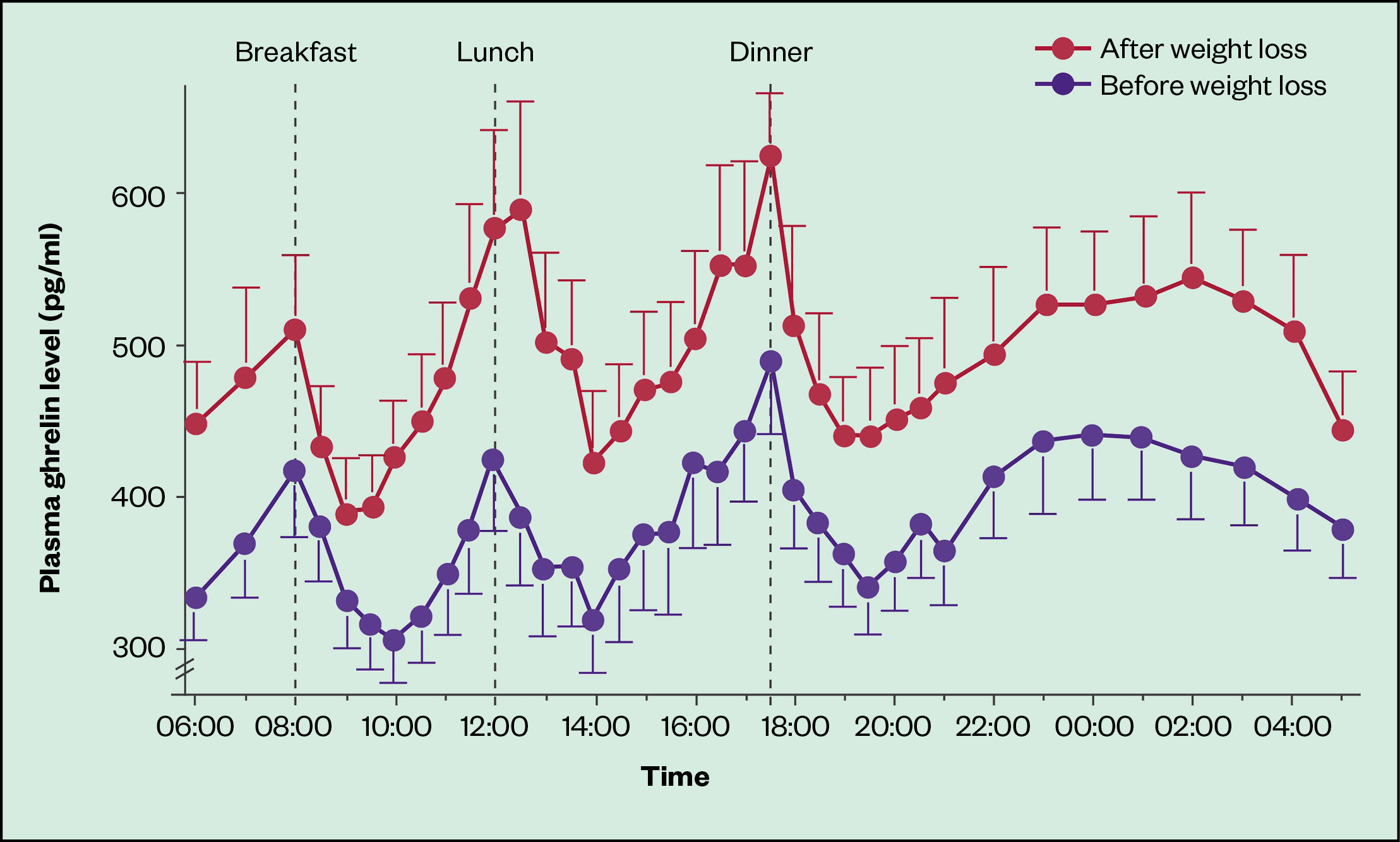

“Just by losing weight alone, this will increase your hunger hormones and decrease your satiety hormones,” explains Philip Newland-Jones, consultant pharmacist and clinical director of the endocrine diabetes service at Southampton General Hospital (see Figure 1)[6].

Ghrelin is a hormone, primarily secreted by the stomach and duodenum, that normally increases in the blood before meals and is thought to stimulate hunger, increase body weight and decrease metabolic rate

The obesity dilemma is not a new issue: pharmacotherapies have long been sought to help support those trying to lose weight. But drug design is challenging owing to the complicated system of signals that regulate weight. There are built-in redundancies that make it hard to have an effect by targeting a single molecule, and key molecules have multiple physiological roles, which can lead to unwanted side effects.

For example, early drugs in use in the 1990s, such as fat-burning dinitrophenol, or amphetamine-related appetite suppressants, such as fenfluramine, have since been found to have dangerous side effects and have been withdrawn from the market.

“Many of these really attractive targets have fallen by the wayside, because of off-target effects,” says John Wilding, an endocrinologist at the University of Liverpool, who is also involved in obesity medicine clinical trials.

Medicines currently licensed in the UK also come with side effects that may not make the weight loss worth it. These include the appetite suppressant Mysimba (naltrexone/bupropion; Orexigen Therapeutics), which was rejected by NICE in 2017, and orlistat, which was first recommended by NICE in 2001. These drugs only induce small amounts of weight loss and it is not clear whether they are any better for obesity than lifestyle modification[7]. They also come with gastrointestinal adverse effects, such as nausea and vomiting for naltrexone/bupropion, and diarrhoea and fatty stools for orlistat, which compel some to discontinue the drugs[7].

Now, newer pharmacotherapies, such as liraglutide and semaglutide, are based on recent discoveries about the involvement of gut–brain hormones in feelings of hunger and fullness. These, and similar drugs, are being put through their paces in clinical trials.

“These new drugs are coming in thick and fast,” Wilding says. “Targeting the body’s natural satiety systems with the gut peptides seems to be most effective.”

Enter incretins

Both liraglutide and semaglutide mimic an incretin hormone called glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), which stimulates insulin release, inhibits glucagon release, slows the movement of food from the stomach and reduces appetite. Although originally designed and approved to treat diabetes, it has been found that these drugs facilitate weight loss in diabetes trials, which led to trials for obesity at higher doses.

Liraglutide and semaglutide have fatty acid attachments that are thought to give them greater access to the brain than other GLP-1 analogues. People who have taken liraglutide or semaglutide report feeling less hungry, more satisfied after a meal and more able to control food cravings.

Recent clinical trials of semaglutide show unprecedented amounts of weight loss. A phase III clinical trial called STEP 1 (‘Semaglutide treatment effect in people with obesity’) involving 1,961 participants with obesity found that weekly subcutaneous injections of semaglutide, in addition to lifestyle intervention, produced an average of 14.9% body weight loss compared with 2.4% in those who received placebo after 68 weeks[8].

Semaglutide is a game changer when it comes to treatments for obesity

Carel le Roux, obesity physician at University College Dublin

Around 86% of the participants on semaglutide lost at least 5% of their body weight, which is considered a clinically meaningful amount that can bring health benefits, compared with 32% of participants in the placebo group. Furthermore, 32% of those taking the drug lost 20% or more of their body weight — a weight reduction on par with that reported one to three years following bariatric surgery[8].

“That’s a game changer when it comes to treatments for obesity,” says le Roux.

The trial also showed improvements in the complications associated with obesity, including blood pressure, lipids, blood glucose, metabolic syndrome and quality of life.

“The bottom line there is [that] everything improved,” says Wilding, who was lead author of the study.

Trial participants taking semaglutide did report gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea and diarrhoea, more often than those in the control group; however, these adverse events were temporary and, to avoid overpowering participants with these side effects, the trial gradually titrated up to the full 2.4mg semaglutide dose over 16 weeks.

In the end, nearly 90% of participants stayed with the trial. This, along with the wide use of the drug in diabetes, offers some assurance regarding its overall safety.

The STEP 8 phase III trial, results of which were published in January 2022, directly compared semaglutide and liraglutide. This found that weekly injections of semaglutide outperformed daily doses of liraglutide: mean body weight change from baseline to 68 weeks was -15.8% in the semaglutide group compared with -6.4% in the liraglutide group[9].

However, stopping semaglutide results in weight gain, according to a trial published in 2021. In the this trial, called STEP 4, all participants took semaglutide for 20 weeks before a subset was switched to placebo[10]. At 20 weeks, mean weight loss was 10.6% of body weight but, at 68 weeks, those who were switched to placebo regained 6.9% of their 20-week weight. This was compared with the 7.9% additional weight loss of those who remained on semaglutide.

This finding suggests that taking semaglutide is not a quick fix for obesity, but rather part of an arsenal that can be used for its long-term management as a chronic condition.

But, how long can a medicine like semaglutide be taken? Results from the STEP 5 trial showed that taking semaglutide for two years resulted in weight loss comparable to the shorter STEP 1 trial with a similar safety profile, though the results are yet to be published[11].

This raises the idea of an intermittent therapy, in which people stop taking the medicine after they have achieved their weight loss, then restart it when they’ve regained a certain amount of weight.

“That would save drug costs and unnecessary exposure to medicine,” Wilding says. “But it has not yet been tested for semaglutide.”

Re-tooling the clinics

Semaglutide has been approved for obesity treatment in the UK and, in February 2022, NICE issued draft guidance recommending the drug to adults with at least one weight-related condition, such as diabetes, and a BMI of at least 35[4]. It has also been recommended exceptionally to people with a BMI of 30.0 to 34.9 if they are referred to tier 3 services based on criteria laid out in NICE’s obesity clinical guideline[12]. The final semaglutide guidance is expected to be published later in 2022[4]

In the meantime, other potential drugs are making their way through the pipeline, some of which mimic multiple gut peptides. For example, tirzepatide (Eli Lilly) targets receptors for both GLP-1 and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP). Eli Lilly announced promising topline results from the first phase III trial, SURMOUNT-1, involving around 2,500 participants, in April 2022. The results suggest that, after 72 weeks of treatment, those taking 15mg tirzepatide lost up to 22.5% (24kg) of their body weight, compared with an average weight loss of 2.4% (2kg) in the placebo group[13].

An early phase Ib trial has tested a combination of semaglutide and cagrilintide (Novo Nordisk), a molecule that mimics the satiety hormone amylin[14]. In the same way as semaglutide, this drug is administered subcutaneously.

As these drugs make their way through clinical trials, adjustments need to be made in weight management clinics.

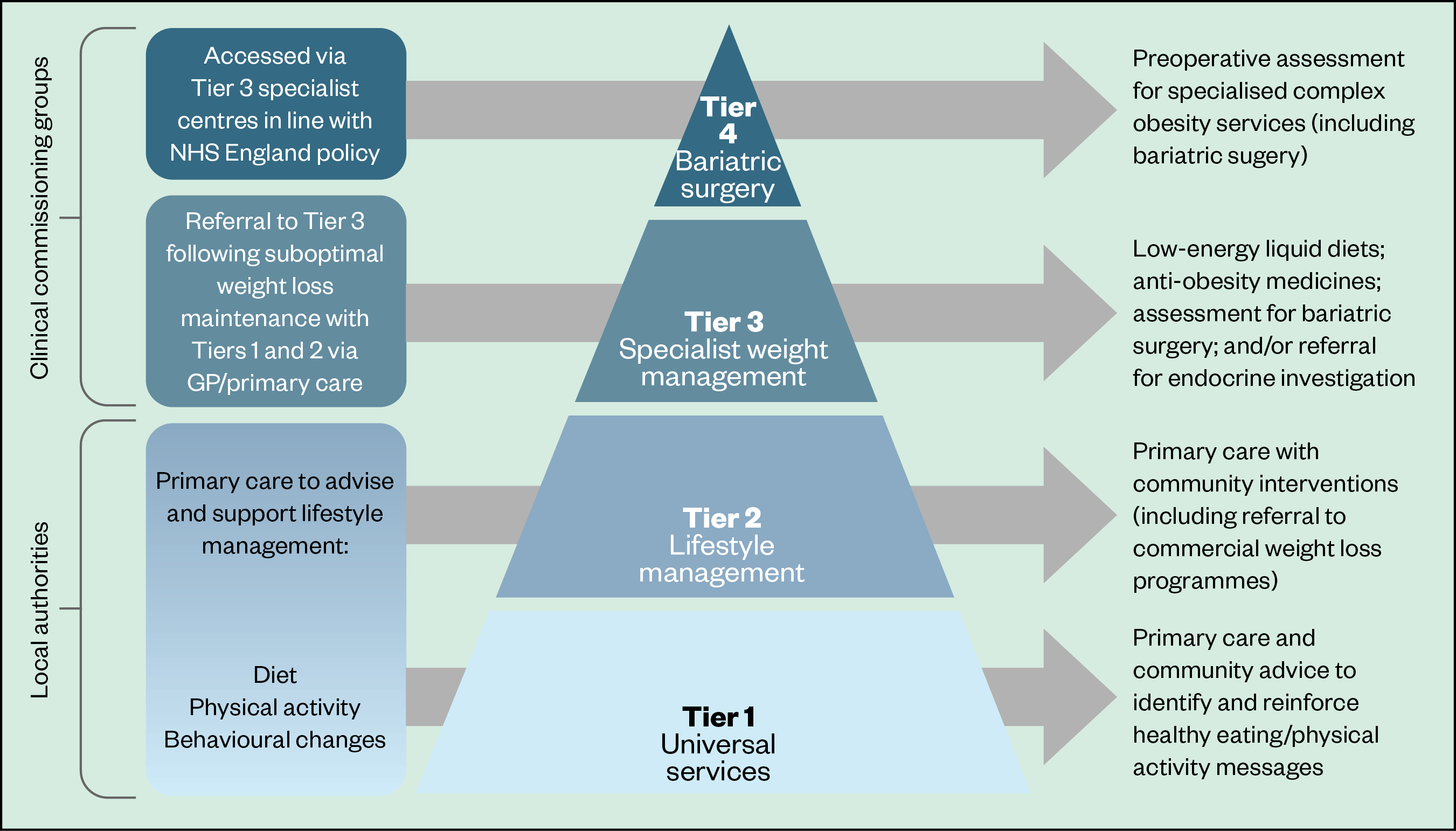

In the UK, there is currently a tiered system of caring for people who are overweight or obese, with gradually increasing levels of intervention and expertise (see Figure 2).

Tiers 1 and 2 involve community-based lifestyle interventions, such as encouraging healthy eating and physical activity. Community pharmacists can play a part in these early interventions — since January 2022, pharmacy teams have been able to refer adults living with obesity to a 12-week online NHS weight management programme.

[There’s] a big difference in the access to these medicines nationwide

Philip Newland-Jones, consultant pharmacist and clinical director of the endocrine diabetes service at Southampton General Hospital

Tier 3 is where medicines are introduced with the guidance of a specialist team, and in Tier 4 comes referral for bariatric surgery.

Despite this organised structure, the reality is that access to obesity medicines is uneven. This is because around a third of obesity services are outsourced to private healthcare teams that cannot easily access NHS pricing for drugs such as liraglutide. As a result, as Newland-Jones explains, they do not prescribe it.

“So that’s a gap in this system that’s led to a big difference in the access to these medicines nationwide,” he adds.

“It’s very easy to get them in some areas, and in others we’ve not had a single prescription.”

Choices

These new medicines could assist people who do not want the permanence of bariatric surgery and may even play a role for those who have had it, like Clare.

Clare’s surgery had dramatic results: he lost half of his body weight in a year and was able to start doing more, including engaging more meaningfully with his family and walking about freely.

I’ve seen with my own eyes that most peoples’ problems occur after they’ve been discharged

Ken Clare, patient

“I walked to the city centre in Liverpool, where I hadn’t been for years, and I couldn’t believe how small it was because, before [the surgery], it had been so difficult to walk so far,” he says.

After surgery, patients are followed by the weight management service for two years, but problems with excess skin, weight regain or psychological issues commonly arise up to five years post surgery.

“I’ve seen with my own eyes that most peoples’ problems occur after they’ve been discharged,” says Clare, who manages a website and support group for people who have had or are considering bariatric surgery.

“So patients will want a choice of a range of treatments.”

- 1Prevalence of obesity among adults, BMI >= 30 (crude estimate) (%). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/prevalence-of-obesity-among-adults-bmi-=-30-(crude-estimate)-(-) (accessed 29 Mar 2022).

- 2Recalde M, Roel E, Pistillo A, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 627 044 COVID-19 patients living with and without obesity in the United States, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Int J Obes (Lond) 2021;45:2347–57. doi:10.1038/s41366-021-00893-4

- 3Yang J, Hu J, Zhu C. Obesity aggravates COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol 2021;93:257–61. doi:10.1002/jmv.26237

- 4Semaglutide for managing overweight and obesity [ID3850]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-ta10765 (accessed 29 Mar 2022).

- 5Tackling obesity: empowering adults and children to live healthier lives. GOV.UK. 2020.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/tackling-obesity-government-strategy/tackling-obesity-empowering-adults-and-children-to-live-healthier-lives#a-call-to-action (accessed 29 Mar 2022).

- 6Cummings DE, Weigle DS, Frayo RS, et al. Plasma Ghrelin Levels after Diet-Induced Weight Loss or Gastric Bypass Surgery. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1623–30. doi:10.1056/nejmoa012908

- 7Shi Q, Wang Y, Hao Q, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2022;399:259–69. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01640-8

- 8Wilding J, Batterham R, Calanna S, et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med 2021;384:989. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2032183

- 9Rubino D, Greenway F, Khalid U, et al. Effect of Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Daily Liraglutide on Body Weight in Adults With Overweight or Obesity Without Diabetes: The STEP 8 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2022;327:138–50. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.23619

- 10Rubino D, Abrahamsson N, Davies M, et al. Effect of Continued Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Placebo on Weight Loss Maintenance in Adults With Overweight or Obesity: The STEP 4 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021;325:1414–25. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.3224

- 11WegovyTM demonstrated significant and sustained weight loss in two-year study in adults with obesity. Novo Nordisk. 2021.https://www.novonordisk-us.com/content/nncorp/us/en_us/media/news-archive/news-details.html?id=85378 (accessed 29 Mar 2022).

- 12Obesity: identification, assessment and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2014.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg189 (accessed 29 Mar 2022).

- 13A Study of Tirzepatide (LY3298176) in Participants With Obesity or Overweight (SURMOUNT-1). ClinicalTrials.gov. 2019.https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04184622 (accessed 29 Mar 2022).

- 14Enebo L, Berthelsen K, Kankam M, et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of concomitant administration of multiple doses of cagrilintide with semaglutide 2·4 mg for weight management: a randomised, controlled, phase 1b trial. Lancet 2021;397:1736–48. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00845-X