Science Photo Library

Rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are rising — a backwards slide since the height of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, when education in STI prevention was made a public health priority[1]

.

Cases of most STIs have increased globally since 2012, with the World Health Organization (WHO) recording 376 million new cases in 2016

[2]

. “People tend to have more risky behaviours [now] and don’t necessarily protect themselves when engaging in sex,” explains Emilie Alirol, STI project leader at the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP).

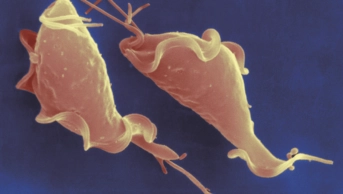

One of GARDP’s main targets is gonorrhoea — an STI currently showing alarming levels of drug resistance.

A 2016 WHO survey revealed that 51 of the 77 countries (66%) monitoring susceptibility to extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs) had described resistant gonococcal isolates; additionally, 47 of the 58 countries (81%) monitoring azithromycin susceptibility and 70 of the 72 countries (97%) monitoring ciprofloxacin susceptibility had also described cases of gonorrhoea resistant to these antibiotics[3]

.

Lori Snyder, a microbiologist at Kingston University in London, explains that the causative agent, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, is able to take up DNA from its environment throughout its growth cycle, speeding up its ability to become resistant.

Researchers across the world are pursuing three main strategies to tackle the rising threat of resistant STIs. First, better diagnostics, which can quickly detect drug-resistant strains, are being developed so people can be tested and treated appropriately within the same appointment. Second, new treatments are being sought to overcome resistance to these ever-changing bacteria. And, finally, vaccines that offer long-term immunity are being investigated to try to prevent the spread of resistant strains.

1. Developing better diagnostics

Test results for STIs can take up to a week and one study showed that 20% of patients who test positive fail to return for treatment within 30 days of screening[4]

.

It’s important that you diagnose people not only accurately, but quickly

“It’s important that you diagnose people not only accurately, but quickly,” says Anna Dixon, chief technology officer of diagnostics company Binx Health, based in Bath, Somerset, which is developing a desktop testing platform based on the polymerase chain reaction.

“Often people are asymptomatic, so the urgency may not come across,” Dixon adds. “Having a test where you can test and treat in the same visit has huge benefits.”

The technology in Binx Health’s testing platform was developed by Chris Frost, professor of medical statistics at the University of Bath[5]

.

“The novel part … is our electrochemical detection,” explains Dixon. “This works by having a length of DNA we call a ‘probe’, to which we attach an electronic label. That probe is specific to targets within the [STI] that we’re looking for.”

The test can be completed in about 30 minutes and it could eventually test for up to 20 infections at once.

To follow its current tests for chlamydia and gonorrhoea, Binx Health is working on diagnostics for Trichomonas vaginalis and Mycoplasma genitalium.

Another important advance is the ability to detect antibiotic-resistant STI strains. Binx Health is currently involved in ongoing research with St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust in London to develop an assay to detect fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin)-resistant gonorrhoea.

Ciprofloxacin is currently not recommended for the treatment of gonorrhoea, but Dixon says there are still strains of gonorrhoea that are susceptible to fluoroquinolone treatment: “So, if you can find those people, that opens up the treatment options,” she adds.

2. Hunting for novel antibiotics

Better diagnosis is just the first piece of the puzzle — new treatments are also needed, particularly for gonorrhoea.

In early 2019, the UK guidelines were updated to recommend intravenous ceftriaxone monotherapy for gonorrhoea, dropping oral azithromycin which had been part of dual treatment since 2011. But, with ceftriaxone resistance on the rise, the hunt for a new antibiotic has become a priority.

GARDP has found a potential candidate in zoliflodacin, which it began co-developing with Boston-based company Entasis therapeutics (an AstraZeneca spin-off) in 2017.

Zoliflodacin is the first in a novel class of antibiotics and has potent in vitro activity against N. gonorrhoeae, including strains resistant to fluoroquinolones and ESCs, such as ceftriaxone.

Results of a phase II trial showed that the drug cured all rectal gonorrheal infections, although it did not work as well in patients with pharyngeal gonorrhea infections, curing 67–78% of patients overall[6]

. Phase III trials are planned in the Netherlands, South Africa, Thailand and the United States.

People get exposed repeatedly during their lifetime and that contributes to resistance emerging

Another experimental oral antibiotic in the pipeline is gepotidacin, a topoisomerase inhibitor being developed by GSK, which works by selectively interacting with two bacterial enzymes that are vital for bacterial replication[7]

.

Gepotidacin has also gone through phase II trials, showing it to be more than 95% effective against uncomplicated gonorrhoea[8]

.

Both of these drugs are being developed exclusively for gonorrhoea. “We are trying very hard to embed sustainability into the [GARDP] programme,” explains Alirol. “With the current drugs, they’re being used for all kinds of infection, so people get exposed repeatedly during their lifetime and that contributes to resistance emerging.”

At Kingston University, Snyder is taking a different approach to treating gonorrhoea, particularly for neonatal conjunctivitis.

“For women particularly, gonorrhoea infections can show no symptoms. Then a woman gives birth to an infant and that infection spreads to the [infant’s] eyes — within 24 hours that can lead to an eye infection that can cause lifelong blindness,” she says.

To combat this, Snyder is developing an eye drop based on the antimicrobial effects of some fatty acids that are able to disrupt the microbial membrane[9]

. Unlike antibiotics, these antimicrobials work on several targets, which gets around the problem of resistance.

“We grew the bacteria in sub-lethal concentrations of our active ingredient to see if the bacteria could mutate and become resistant and, over [around 2 months and 20 changes of medium], we didn’t see any mutants appear,” says Snyder. “So, we’re quite hopeful for our new treatment.”

Her team is working with laboratories in the UK and Africa on pre-clinical testing of two lead candidates specifically for eye drops, but she is exploring another five candidates to treat wider gonococcal infections.

3. Vaccinating for long-term immunity

Prevention is, of course, better than cure. The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, Gardasil (Merck Sharp & Dohme), which protects against four types of HPV — several of which cause most cervical cancers — is just one example which has no doubt saved many lives.

“In the long term, vaccines must be part of the solution,” says Alirol.

In May 2019, the US National Institutes of Health acknowledged the importance of STI vaccines by announcing US$41.6m in funding over five years for research into syphilis, gonorrhoea and chlamydia vaccines.

“People in the field knew it was important, but — in the general medical community — I don’t think it was a priority,” says Justin Radolf, a microbiologist from the University of Connecticut, in the United States, and recipient of an interdisciplinary grant to develop a syphilis vaccine. The sudden rise of syphilis infections over the past decade has started to change that: “There’s been a recognition of how serious the problem is,” Radolf says.

One of the challenges has been finding vaccines that create long-term immunity.

Snyder explains that, with gonorrhoea, even those who become infected are not immune after the infection is cleared because the bacteria are able to quickly change their surface protein structures. “A person can be cleared of N. gonorrhoea and then become reinfected by the exact same strain if their partner doesn’t [also] get treated.”

Vaccines administered to genital tissues are not taken up very well

It is also difficult to create the local mucosal immunity needed — a specific immune response that can be triggered in mucosal tissues, such as those found in the gastrointestinal, respiratory and the female genital tracts.

“We know that the vaccines administered to genital tissues are not taken up very well by the local antigen-presenting cells — the first cells that take up the vaccine,” explains Linda Klavinskis, an immunologist and vice dean of postgraduate research in the Faculty of Life Sciences and Medicine at King’s College London (KCL).

Attempts to vaccinate the genital tract directly are unlikely to encourage patient uptake, but Klavinskis’s viral immunology group at KCL has been working on a method that might enable vaccines to generate better protection against STIs, even when administered remotely.

Klavinskis has discovered how to generate a type of CD8 T-cell response whereby the cells become resident in the genital tissues. “This is a new field that’s only opened up in the past ten years,” she explains.

The T-cells can be generated using an adenovirus — a common type of virus that infects the lining of the eyes, airways, lungs, intestines, urinary tract and nervous system, and causes cold-like symptoms — as a vector that can display components of the vaccine to the immune system.

“The vaccine generates an immune response in the skin-draining lymph nodes and then a proportion of those T-cells traffic to other body sites,” says Klavinskis. In the genital tract, a small amount of inflammation will then activate signaling proteins called chemokines, which marshal further cell types, such as innate lymphoid cells and monocytes, to trigger the CD8 T-cell immune response[10]

.

So far, Klaviniskis’s team has cloned in genes from HIV, but their system could be used to create effective protection against many other STIs by cloning in the appropriate gene for the protein of interest. However, this is the next problem, she explains.

“Trying to get the best kind of immunogen — the best protein or construct that targets the virus to induce a protective response — is very difficult.”

The possibility of a gonorrhoea vaccine was also recently given a boost from reports that a meningitis B vaccine, previously given in New Zealand between 2004–2006, gave some protection against gonorrhoea[11]

.

“The protection is very minor, only 30%, but it’s still very encouraging because, until then, it was believed that immunity couldn’t be generated against gonorrhoea,” says Alirol.

There’s got to be resources for people whose job it is to go out and identify these patients

Treatments for other STIs have also had success in this field. In August 2019, the first chlamydia vaccine (CTH522) reached phase I trials in Denmark, based on an outer membrane protein of the Chlamydia trachomatis bacterium[12]

.

Of course, even with current progress in new diagnostics, treatments and vaccinations, the reported increases in STI incidence shows that education is still crucial.

“It’s not easy to get people to come out of the shade and admit that they may have to be tested,” says Radolf. “There’s got to be resources for people whose job it is to go out and identify these patients.”

References

[1] Mohammed H, Blomquist P, Ogaz D, et al. Sex Transm Infect 2018 Dec;94(8):553-558. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053273

[2] Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Korenromp E et al. Bull World Health Organ 2019;97(8):548–562. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.228486

[3] Wi T, Lahra M, Ndowa F et al. PLoS Med 2017;14(7):e1002344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002344

[4] Schwebke J, Sadler R, Sutton J, et al. Sex Transm Dis 1997;24:181–4. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199704000-00001

[5] Pearce D, Shenton D, Holden J & Gaydos CA. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2011;58(3):755–758. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2010.2095851

[6] Taylor S, Marrazzo J, Batteiger B et al. N Engl J Med 2018; 379(19):1835-1845. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706988

[7] Jacobsson S, Golparian D, Scangarella-Oman N & Unemo M. J Antimicrob Chem 2018;73(8):2072–2077. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky162

[8] Taylor S, Morris D, Avery A et al. Clin Infect Dis 2018;67(4):504–512. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy145

[9] Butt U, ElShaer A, Snyder L et al. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2018;8(1). doi: 10.3390/nano8010051

[10] Zaric M, Becker P, Hervouet C et al. Nature Commun 2019;10(1):2214. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09969-2

[11] Paynter J, Goodyear-Smith F, Morgan J et al. Vaccines (Basel) 2019;7(1). doi: 10.3390/vaccines7010005

[12] Abraham S, Juel H, Bang P et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2019;19(10):1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30279-8