David M Phillips / Science Photo Library

Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) is the most common non-viral sexually transmitted infection (STI) with an estimated 156.3 million cases worldwide in 2020. There is significant regional variation; the highest rates are in Africa with a prevalence of 12% in females and 1.2% in males, contrasting with South East Asia with a prevalence of 2.8% and 0.2%, respectively. In England in 2019, there were 9,474 cases recorded in females and 761 in males. In the UK, TV tends to be clustered in specific urban areas, especially London and Birmingham, among black ethnic minorities and in prison inmates[3]. Unlike other STIs, TV is more commonly found in women over the age of 25.

Transmission

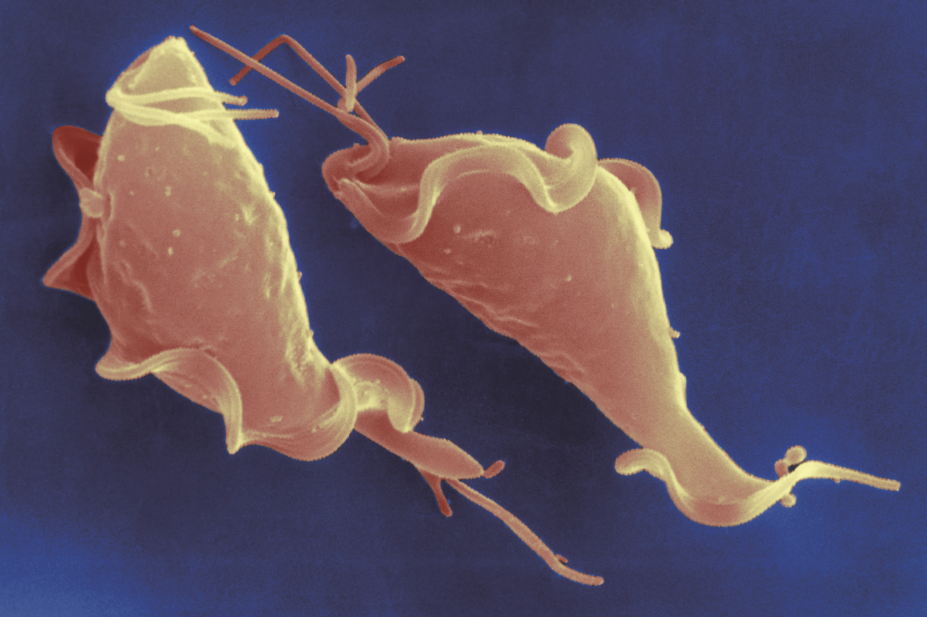

TV is a flagellated protozoon and, in adults, transmission is almost exclusively through sexual intercourse and requires intravaginal or intraurethral inoculation of the organism, but it can also be passed on by sharing sex toys with an infected person. In women the organism is found in the vagina, urethra and paraurethral glands. Urethral infection is present in 90% of infected women, although the urethra is the sole site of infection in less than 5% of cases. TV may also be passed from an infected mother to her baby during childbirth. In men infection is usually of the urethra, although trichomonads have been isolated from the subpreputial sac and lesions of the penis.

Symptoms

The majority of infected individuals are asymptomatic. In women, the infection may persist for long periods, possibly months or even years; however, in men it generally persists for less than 10 days, possibly due to the lack of oestrogen[4]

.

Around 10–60% of females are asymptomatic. Symptoms that do occur, usually 5 to 28 days following infection, are not specific for TV and include variable vaginal discharge (Figure 1), vulval itching, dysuria or offensive odour. Occasionally the presenting complaint is of low abdominal discomfort or vulval ulceration: TV infection is associated with pelvic inflammatory disease[5],[6]

. TV infection can have a detrimental outcome on pregnancy and is associated with preterm delivery and low birth weight[7],[8]

.

Figure 1: Trichomonas vaginalis

Source: Dr Isabelle Cartier / ISM / Science Photo Library

Endoscopic image of the interior of a patient’s vagina showing vaginitis (vaginal inflammation) and leucorrhoea (whitish discharge) caused by trichomoniasis

The majority of men are asymptomatic and usually present as sexual partners of infected women. The most common symptoms in men are urethral discharge and/or dysuria. Other symptoms include urethral irritation and urinary frequency. The patient may complain of a copious purulent urethral discharge or symptoms of complications (e.g. prostatitis), although these symptoms are rare[4],[9]

.

There is evidence that trichomonas infection enhances HIV transmission[10],[11],[12]

and there may be an increased risk of TV infection in those who are HIV positive[13]

.

Diagnosis

As the majority of men have no symptoms, and the symptoms in women are non-specific, it is unknown how soon after infection TV can be identified by available tests. Until recently, the mainstay of diagnosis in the UK has been immediate microscopy of vaginal secretions to look for the motile organism. This remains a useful point-of-care test in symptomatic women but, with the advent of nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), it is recognised that NAATs have a much greater sensitivity and specificity, especially in men and asymptomatic women.

Diagnostic testing for TV should be undertaken in women complaining of vaginal discharge or vulvitis, or those found to have evidence of vulvitis and/or vaginitis on examination. Testing in men is recommended for TV contacts, and should be considered in those with persistent urethritis[14]

. Box 1 provides more information on the different sites to sample for men and women.

Decisions about screening should be informed by local epidemiology of TV but should be considered for people in high-prevalence settings (e.g. STI clinics and prisons) and for asymptomatic persons at high risk for infection (e.g. persons with multiple sex partners, exchanging sex for payment, illicit drug use, or a history of STIs).

Symptomatic women are recommended to attend a sexual health clinic where point-of-care microscopy can test for TV. However, this is not available in other settings. With the increased availability of NAATs for TV, more microbiology laboratories are providing testing but this is not universal, especially to settings other than sexual health clinics. Therefore, if TV is suspected, the patient should be advised to attend their local sexual health clinic or the local laboratory should be contacted to establish whether it undertakes TV testing.

Box 1: Sites sampled to establish a diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis

In women:

- Swab taken from the posterior vaginal fornix at the time of speculum examination;

- Self-taken vaginal swabs produce similar results to clinician-taken samples when using nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) for diagnosis.

In men:

- First-void urine, using NAATs.

Microscopy

Microscopy for TV diagnosis (Figure 2) has the advantage that it can be performed near to the patient in a clinic setting[15]

. A sample of vaginal discharge is mixed with a small drop of saline on a glass slide. The wet preparation should be read within 10 minutes of collection because the trichomonads will quickly lose motility and be more difficult to identify. The sensitivity is highest in women presenting with vaginal discharge and visualisation of motile trichomonads in these women indicates the presence of infection. However, the sensitivity is reported to be as low as 45–60% in women and even lower in men; therefore, a negative result should be interpreted with caution. The specificity with trained personnel is high.

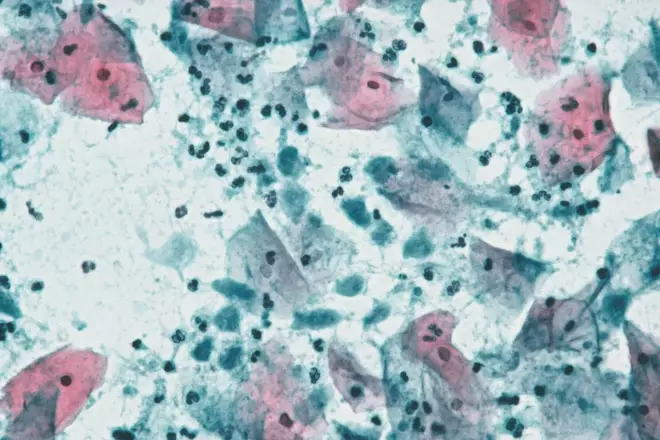

Figure 2: Trichomonas infection under light microscope

Source: Dr E Walker / Science Photo Library

Light micrograph of a cervical smear containing normal squamous cells from the cervix (pink/blue) and Trichomonas vaginalis parasites (smaller blue patches)

Point-of-care tests

There are point-of-care tests for the detection of TV, of which the OSOM Trichomonas Rapid Test (Sekisui Diagnostics) has demonstrated a high sensitivity (80–94%) and specificity (>95%). This test requires no instrumentation, provides a result within 30 minutes and is a suitable alternative to culture or molecular testing in women. It should not be used in men.

Culture

Culture of TV has a higher sensitivity compared with microscopy and can detect TV in men; however, it takes up to five days to produce a result[15]

. Culture was considered the ‘gold standard’ but molecular testing has proven to have a higher sensitivity.

Molecular detection

NAATs, which are the ‘gold standard’, offer the highest sensitivity for the detection of TV and should be the test of choice where resources allow. NAATs can detect TV DNA in vaginal or endocervical swabs and in urine samples from women and men with sensitivities of 88–97% and specificities of 98–99%[16],[17],[18],[19]

. Specific swabs are required depending on the platform used.

Treatment

Nitroimidazoles are the only class of antimicrobial medications known to be effective against TV infections. Systemic antibiotic therapy is required owing to the high frequency of infection of the urethra and paraurethral glands in females. A Cochrane review has found that almost any nitroimidazole drug given as a single dose or over a longer period results in parasitological cure in >90% of cases[20]

. Oral single dose treatment with any nitroimidazole seems to be effective in achieving short term parasitological cure[21],[22]

, but is associated with more frequent side effects than longer oral treatment. There is a spontaneous cure rate in the order of 20–25%. See Box 2 for recommended and alternative treatment regimens.

Box 2: Regimes for Trichomonas vaginalis

Recommended regimen

- Metronidazole 2g orally in a single dose;

or

- Metronidazole 400–500mg twice daily for 5–7 days.

Alternative regimen

- Metronidazole 2g orally in a single dose.

A meta-analysis of single-dose oral metronidazole compared with multidose oral metronidazole for the treatment of TV in women found an increased risk of treatment failure with single dose treatment (RR 1.87 (95% Confidence Intervals 1.23–2.82; p= <0.01).[Howe] A subsequent RCT of metronidazole 500mg twice daily for 7 days versus metronidazole 2g single dose for the treatment of TV in women reported a positive test-of-cure in 11% of the 7-day dose group versus 19% in the single-dose group (relative risk 0·55, 95% CI 0·34–0·70; P=<0·0001)

Metronidazole gel does not reach therapeutic levels in the urethra and perivaginal glands. Since it is less efficacious than oral metronidazole, it is not recommended.

To reduce the possibility of a disulfiram-like reaction, abstinence from alcohol use is recommended during treatment and for 24 hours after completion of metronidazole or 72 hours after completion of tinidazole.

Tinidazole, which has previously been recommended as second line treatment is no longer available.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Metronidazole is likely to cure trichomoniasis, but it is not known whether this treatment will have any effect on pregnancy outcomes[23]

. Meta-analyses have concluded that there is no evidence of teratogenicity from the use of metronidazole in women during the first trimester of pregnancy[24],[25],[26]

. Metronidazole can be used in all stages of pregnancy and during breastfeeding. Symptomatic women should be treated at diagnosis[23]

, although some clinicians have preferred to defer treatment until the second trimester. The British National Formulary advises against high dose regimens in pregnancy[27]

. Metronidazole enters breast milk and may affect its taste. The manufacturers recommend avoiding high doses if breastfeeding, or if using a single dose of metronidazole, breastfeeding should be discontinued for 12–24 hours to reduce infant exposure.

HIV-positive individuals

There are few data available to guide management of TV infection management in HIV-positive individuals. However, a recent randomised clinical trial demonstrated that a 2g single oral dose of metronidazole was not as effective as 500mg of metronidazole twice daily for 7 days for trichomoniasis among HIV-infected women[28]

.

Allergy

There is no effective alternative to 5-nitroimidazole compounds. Hypersensitivity reactions have been reported in patients using metronidazole and tinidazole, and it is unknown whether there is cross reactivity between the two agents. It is important to take an accurate history to establish that a true allergy exists. Adverse reactions that may occur include anaphylaxis, skin rashes, pustular eruptions, pruritis, flushing, urticaria and fever[29]

. In cases of true allergy, desensitisation to metronidazole has been described in case reports and could be considered[30],[31]

. Helms et al. reported data collected from clinicians who consulted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on 59 women with suspected hypersensitivity to metronidazole. All 15 patients who underwent metronidazole desensitisation and were treated with metronidazole had their infections eradicated. Alternative treatment regimens were used for 17 study subjects with a cure rate of only 29.4%[32]

.

Treatment failure

Persistent or recurrent TV is due to inadequate therapy, re-infection or resistance. Therefore, pharmacists and healthcare professionals must check the following:

- Compliance, and exclude vomiting of metronidazole;

- Sexual history for possibility of re-infection and ask if partner(s) have been treated.

A study investigating repeat TV infections at 1 month following metronidazole 2g stat dose found that 7% of HIV-negative women and 10% of HIV-positive women were still infected due to treatment failure, suggesting a significant number of women do not respond to single-dose therapy[33]

. Treatment failure due to antibiotic resistance is increasingly recognised. These women should be seen in a sexual health clinic because management of the infection is challenging. A number will respond to re-treatment with the initial therapy, but other complex regimens with prolonged systemic treatment in combination with local therapy may be required to affect symptom relief and a parasitological cure[34],[35],[36],[37],[38],[39],[40],[41]

.

Follow-up

Tests of cure are only recommended if the patient remains symptomatic following treatment or if symptoms recur[14]

.

General advice

Current sexual partners and any partner(s) in the four weeks prior to presentation should be screened for the full range of STIs and treated for TV irrespective of the results of investigations. Patients should be advised to avoid sexual intercourse for at least one week and until they and their partner(s) have completed treatment and follow-up[14]

.

Patients should be given a detailed explanation of their condition with particular emphasis on the long-term implications for the health of themselves and their partner(s). This should be reinforced by giving them clear and accurate written information. See Box 3 for general information to provide patients with.

Box 3: General information to be given to patients to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted infections

- Have a check-up before having sex with a new partner;

- Always use condoms for vaginal or anal sex, especially with new or casual partners;

- For oral sex, cover the penis with a condom, or the female genitals and male / female anus with a latex or polyurethane square;

- Avoid sharing sex toys. If patients do share them, they should be washed or covered with a new condom before anyone else uses them.

Patients can also be provided with information leaflets from the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH; https://www.bashh.org/pils)

This article has been reviewed and updated by the expert author to ensure it remains relevant, following its original publication in October 2017.

References

[1] World Health Organization (WHO). Global incidence and prevalence of selected sexually transmitted infections — 2008. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75181/1/9789241503839_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed October 2017)

[2] Public Health England (PHE). All STI diagnoses & services by gender & sexual risk, 2012–2016. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/626365/2016_Table_4_All_STI_diagnoses___services_by_gender___sexual_risk.pdf (accessed October 2017)

[3] Mitchell HD, Lewis DA, Marsh K et al. Distribution and risk factors of Trichomonas vaginalis infection in England: an epidemiological study using electronic health records from sexually transmitted infection clinics, 2009–2011. Epidemiol Infect 2014;142:1678–1687. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813002902

[4] Krieger JN. Trichomoniasis in men: old issues and new data. Sex Transm Dis 1995;22(2):83–96. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199503000-00003

[5] Wolner-Hanssen P, Kreiger JN, Stevens CE et al. Clinical manifestations of vaginal trichomoniasis. JAMA 1989;264:571–576. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03420040109029

[6] Hollman D, Coupey SM, Fox AS et al. Screening for Trichomonas vaginalis in high-risk adolescent females with a new transcription-mediated nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT): associations with ethnicity, symptoms, and prior and current STIs. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2010;23:312–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2010.03.004

[7] Saurina GR & McCormack WM. Trichomoniasis in pregnancy. Sex Trans Dis 1997;24:361–362. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199707000-00009

[8] Cotch MF, Pastorek JG, Nugent RP et al. Trichomonas vaginalis associated with low birth weight and preterm delivery. Sex Trans Dis 1997;24:353–360. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199707000-00008

[9] Seña AC, Miller WC, Hobbs MM et al. Trichomonas vaginalis infection in male sexual partners: implications for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:114–115. doi: 10.1086/511144

[10] Sorvillo F & Kernott P. Trichomonas vaginalis and amplification of HIV-1 transmission. Lancet 1998;351:213–214.doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78181-2

[11] McClelland RS, Sangare L, Hassan WM et al. Infection with Trichomonas vaginalis increases the risk of HIV-1 acquisition. J Infect Dis 2007;195:698–702. doi: 10.1086/511278

[12] Tanton C, Weiss HA, Le Goff J et al. Correlates of HIV-1 genital shedding in Tanzanian women. PLoS One 2011;6:e17480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017480

[13] Mavedzenge SN, Po BV, Cheng H et al. Epidemiological synergy of Trichomonas vaginalis and HIV in Zimbabwean and South African women. Sex Transm Dis 2010;37:460–466. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181cfcc4b

[14] Sherrard J, Ison C, Moody J et al. United Kingdom national guideline on the management of Trichomonas vaginalis 2014. Int J STD AIDS 2014;25:541–549. doi: 10.1177/0956462414525947

[15] Bickley LS, Krisher KK, Punsalang A et al. Comparison of direct fluorescent antibody, acridine orange, wet mount and culture for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis in women attending a public sexually transmitted disease clinic. Sex Trans Dis 1989;127–131. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198907000-00002

[16] Munson E, Napierala M, Olson Ret al. Impact of Trichomonas vaginalis transcription-mediated amplification-based analyte-specific reagent testing in a metropolitan setting of high sexually transmitted disease prevalence. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:3368–3374. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00564-08

[17] Cosentino LA, Campbell T, Jett A et al. Use of nucleic acid amplification testing or diagnosis of anorectal sexually transmitted infections. J Clin Microbiol 2012;50:2005–2008. doi: 10.1128/jcm.00185-12

[18] Schwebke JR, Hobbs MM, Taylor SNet al. Molecular testing for Trichomonas vaginalis in women: results from a prospective US clinical trial. J Clin Microbiol 2011;49(12):4106–4111. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01291-11

[19] Ginocchio CC, Chapin K, Smith JS et al. Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis and coinfection with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the United States as determined by the Aptima Trichomonas vaginalis nucleic acid amplification assay. J Clin Microbiol 2012;50(8):2601–2608. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00748-12

[20] Forna F & Gülmezoglu AM. Interventions for treating trichomoniasis in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;2:CD000218. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000218

[21] Hager D, Brown ST, Kraus SJ et al. Metronidazole for vaginal trichomoniasis. Seven-day vs single-dose regimens. JAMA 1980;244:1219–1220. doi: 10.1001/jama.1980.03310110029023

[22] Thin RN, Symonds MAE, Booker R et al. Double-blind comparison of a single dose and a five-day course of metronidazole in the treatment of trichomoniasis. Brit J Vener Dis 1979;55:354–356. doi: 10.1136/sti.55.5.354

[23] Gülmezoglu AM & Azhar M. Interventions for trichomoniasis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(5):CD000220. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd000220.pub2

[24] Burtin P, Taddio A, Adburnu O et al. Safety of metronidazole in pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;172:525–529. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90567-7

[25] Czeizel AE & Rockenbauer M. A population based case-control teratologic study of oral metronidazole treatment during pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;105:322–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10094.x

[26] Caro-Paton T, Carvajal A, de diego IM et al. Is metronidazole teratogenic: a meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1997;44:179–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00660.x

[27] British National Formulary (BNF). Metronidazole. Available at: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/mc/bnf/current/PHP3647-metronidazole.htm?q=Metronidazole&t=search&ss=text&tot=101&p=1#_hit (accessed October 2017)

[28] Kissinger P, Mena L, Levison J et al. A randomized treatment trial: single versus 7-day dose of metronidazole for the treatment of Trichomonas vaginalis among HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;55:565–571. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181eda955

[29] Zentiva. Summary of product characteristics for Flagyl 400mg tablets. Available at: http://www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/21216/SPC/Flagyl+400mg+Tablets/ (accessed October 2017)

[30] Pearlman MD, Yashar C, Ernst S et al. An incremental dosing protocol for women with severe vaginal trichomoniasis and adverse reactions to metronidazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;174:934–936. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70329-0

[31] Kurohara ML, Kwong FK, Lebherz TB et al. Metronidazole hypersensitivity and oral desensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1991;88:279–280. PMID: 1880329

[32] Helms DJ, Mosure DJ, Secor WE et al. Management of trichomonas vaginalis in women with suspected metronidazole hypersensitivity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198(4):370.e1–370.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.10.795

[33] Kissinger P, Secor WE, Leichliter JS et al. Early repeated infections with Trichomonas vaginalis among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:994–999. doi: 10.1086/529149

[34] Kirkcaldy RD, Augostini P, Asbel LE et al. Trichomonas vaginalis antimicrobial drug resistance in 6 US cities, STD Surveillance Network, 2009–2010. Emerg Infect Dis 2012;18:939–943. doi: 10.3201/eid1806.111590

[35] Bosserman EA, Helms DJ, Mosure DJ et al. Utility of antimicrobial susceptibility testing in Trichomonas vaginalis-infected women with clinical treatment failure. Sex Transm Dis 2011;38:983–987. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318224db39

[36] Das S, Huengsberg M & Shahmanesh M. Treatment failure of vaginal trichomoniasis in clinical practice. Int J STD AIDS 2005;16:284–286. doi: 10.1258/0956462053654258

[37] Schwebke JR & Barrientes FJ. Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis isolates with resistance to metronidazole and tinidazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006;50:4209–4210. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00814-06

[38] Crowell AL, Sanders-Lewis KA & Secor WE. In vitro metronidazole and tinidazole activities against metronidazole-resistant strains of Trichomonas vaginalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003;47:1407–1409. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.4.1407-1409.2003

[39] Sobel JD, Nyirjesy P & Brown W. Tinidazole therapy for metronidazole-resistant vaginal Trichomoniasis. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33:1341–1346. doi: 10.1086/323034

[40] Mammen-Tobin A & Wilson JD. Management of metronidazole-resistant Trichomonas vaginalis— a new approach. Intl J STD & AIDS 2005;16:488–490. doi: 10.1258/0956462054308422

[41] Goldman LM, Upcroft JA, Workowski K et al. Treatment of metronidazole-resistant Trichomonas vaginalis. Sexual Health 2009;6:345–347. doi: 10.1071/SH09064