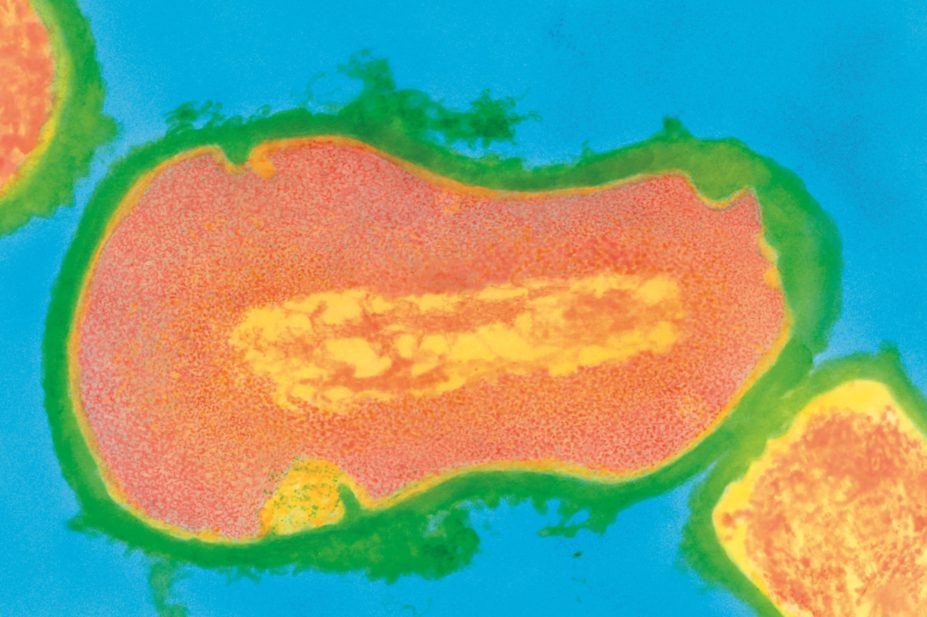

Dr Kari Lounatmaa / Science Photo Library

Most people suffer from acne at some point in their lives. It is commonly perceived as a self-limiting disease of adolescence but for many people it persists into adulthood and is often described as a chronic inflammatory skin disease. In the UK, it accounts for more than 3.5 million GP visits each year[1]

.

Prevalence and characteristics

Nearly 80% of teenagers have acne and up to 20% will have moderate or severe disease[2]

. It is most common among those aged 14–19 years, although it can start earlier and persist into some patients’ 30s and 40s.

Acne typically starts around the time of puberty, with the appearance of closed comedones (known as whiteheads) and open comedones (blackheads) on the face. A closed comedone is a flesh-coloured bump with no visible opening; open comedones are characterised by an opening filled with oxidised melanin, which appears black.

Comedones can be accompanied by inflammatory papules, pustules, nodules or, in severe cases, cysts. The skin is often reddened and appears greasy.

Causes of acne

Acne is an androgen-dependent disorder of pilosebaceous follicles (the hair follicle and the attached sebaceous gland). The areas of the body with the highest density of pilosebaceous follicles are the face, neck, upper chest, shoulders and back.

The starting point for acne is the development of the microcomedone, which cannot be seen or felt on clinical examination. This can develop into a closed comedone, open comedone, papule, pustule, nodule or cyst.

It is believed that a number of events occur more or less simultaneously resulting in microcomedone formation. Increased androgen production (in both young men and women at puberty) causes rapid proliferation and shedding of skin cells lining the sebaceous follicles. This leads to plugging of the outlet. At the same time there is increased sebum secretion. The net result is a small swelling.

It is believed that a number of events occur more or less simultaneously resulting in microcomedone formation.

The resulting lipid-rich, anaerobic environment is colonised by Propionibacterium acnes, an anaerobe that is part of the normal cutaneous flora in adults. This colonisation of the plugged outlet can lead to inflammation with swelling, redness, pain and release of inflammatory mediators into surrounding skin. Inflamed follicles can rupture and extend the process into the surrounding tissue, resulting in the formation of characteristic inflammatory acne lesions.

There is a genetic predisposition to acne although, as yet, little is known about the specific genes and mechanisms involved. The genes for cytochrome P450 isoenzyme 1A1 and steroid 21-hydroxylase, which influences androgen production in the adrenal gland, have both been implicated.

In addition, genetic polymorphisms against interleukin 1 alpha, insulin-like growth factor 1, tumour necrosis factor 1 and its Type-2 receptor, Toll-like receptor 2 and the androgen receptor have been detected. These might explain familial predisposition to acne.

Acne can be triggered or exacerbated by a number of factors. These include:

- Mechanical obstruction, e.g., collars, helmets

- Greasy cosmetics, e.g., hair pomade, massage oil

- Systemic or topical corticosteroids

- Increased androgen production, e.g., androgen-secreting tumours, anabolic steroids, polycystic ovary syndrome

- Drugs, e.g., antiepileptics

- Smoking

It is not known why smoking affects acne. However, smoking causes a number of metabolic changes to the skin, including altering sebum composition.

Classification

The classification of acne is important because it guides treatment strategies. There is no standardised, universal grading scheme for acne but the following categories are commonly used.

Comedonal acne only involves comedones and is usually limited to the face.

Mild to moderate

papulopustular acne involves comedones and a few inflammatory lesions. It is usually limited to the face.

Severe papulopustular acne and moderate nodular acne both involve comedones and inflammatory papules and pustules. Patients may also have mild acne on their back and upper chest.

Severe nodular acne and conglobate acne both involve facial acne and widespread acne on the back and upper chest, including nodules and cysts. Conglobate acne is a very severe form of nodulocystic acne in which inflammatory lesions predominate and run together and often form exudates or bleed. It is a rare variant of acne

Types of acne

Source: Science Photo Library

(1) Mild acne: The patient has some inflammatory lesions and pustules.

(2) Moderate acne: The patient has several pustules and inflammatory lesions but the acne limited to the face.

(3) Severe acne: Lesions are present on the back and the patient has a large number of inflammatory papules and pustules.

Comedones are only present in acne and can be used to confirm the diagnosis. However, other conditions can have some of the features of acne and need to be considered. These include papulo-pustular rosacea; folliculitis and boils; sycosis barbae; milia; perioral dermatitis; and acneiform eruption, which is commonly seen during treatment with endothelial growth factor inhibitors such as cetuximab and gefitinib.

Most cases of acne can be diagnosed clinically. Laboratory investigations are only necessary if signs and symptoms suggest hyperandrogenism (e.g., in suspected polycystic ovary syndrome).

Complications

Acne can cause extensive and permanent scarring; about 20% of patients are estimated to have visible scarring. Acne scars are typically atrophic, and are often described as “ice-pick” scars because it appears tissue has been removed. Hypertrophic or keloid scars occur less frequently.

Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation – darkening of the skin at the site of healed inflammatory lesions – can occur, especially in people with darker skin. Although all scars will fade with time, some patients find the appearance of hyperpigmentation distressing.

The cosmetic appearance of acne or scars caused by acne can cause psychological problems, such as anxiety and depression and low self-esteem. Studies have shown that people with acne have levels of social and psychological disability that are equivalent to those seen in asthma, epilepsy and diabetes[3]

.

Frequently asked questions

Is acne caused by poor hygiene?

Acne is not caused by poor hygiene and not improved by vigorous cleansing. Excessive washing and use of abrasive cleansers can make acne worse by stimulating further sebum secretion.

Does diet affect acne?

There is limited evidence that diets high in dairy products and those with a high glycaemic load might make acne worse[4]

. No direct link has been found between acne and consumption of chocolate, shellfish or fatty foods.

Will cosmetics make acne worse?

It is best to avoid heavy, greasy make-up. Products that are oil-free and non-comedogenic can be used, and products such as cover creams and green-tinted foundation can be useful to conceal lesions.

Does stress aggravate acne?

Yes. Patients often find that stress aggravates acne and this has been confirmed in studies[5]

.

Does acne flare before a period?

A premenstrual acne flare occurs in about 60% of women with acne.

Does sunshine help?

There is no robust evidence for the benefit of sunlight in acne3 .

Is acne infectious?

Acne is not infectious and cannot be passed to other people.

Treatment

The treatments available for acne all combat one or more of the underlying causes of the disease. They mainly work by preventing the development of new lesions and so the response to treatment often appears to be slow.

Benzoyl peroxide is an oxidising agent that has a bactericidal action against P. acnes and weak anticomedonal activity. It is effective for treating both inflammatory and non-inflammatory acne. In practice, benzoyl peroxide is often the first-line option for acne because people tend to seek treatment once signs of inflammation appear.

A range of preparations is available, including gels, lotions, creams, soaps and washes. Dose-related redness, dryness, stinging and scaling are the most common side effects, and treatment should start with the lowest strength and be increased if necessary.

Products containing benzoyl peroxide should be applied to the whole of the affected area, not just the spots; for spots on the face, the entire face should be treated.

For patients with sensitive skin, it is best to start by applying benzoyl peroxide once a day or every other day, building up gradually to twice a day. Application of a light (oil-free) moisturiser 30–60 minutes after treatment can help to minimise irritation.

Patients should be advised that benzoyl peroxide will bleach clothes, towels, bed linen and hair, and they should wash their hands thoroughly after applying it.

Treatment can take at least six to eight weeks before a clear improvement is noticeable. If there is no obvious improvement after this time, pharmacists should check the patient’s adherence to the treatment and refer the patient to the GP if appropriate.

Topical retinoids (e.g., tretinoin cream 0.025%, tretinoin gel 0.01% and adapalene 0.1%) normalise keratinocyte shedding and prevent the formation of new microcomedones. Therefore topical retinoids tackle acne effectively at an early stage. Topical retinoid treatment can show improvements to acne in weeks, with a maximum benefit seen after three or four months[6]

.

Topical retinoids are the treatment of choice for comedonal (non-inflammatory) acne. Adapalene is applied once a day in the evening. Tretinoin is applied once or twice a day. Topical retinoids should be applied to the whole of the acne-prone area, not just to visible acne lesions.

Dose-related side effects include erythema, burning, skin peeling and dryness, which can limit the use of topical retinoids. Retinoids also increase the risk of sunburn. Patients should be warned to avoid sunbeds and excessive exposure to sunlight, and advised to use sun creams with a sun protection factor of at least 15.

Transdermal absorption of adapalene and tretinoin is low. However, because of the known teratogenicity of systemic retinoids, neither product should be used during pregnancy. Adapalene should only be used by women taking contraceptive precautions.

If a topical retinoid is combined with another topical treatment (e.g., benzoyl peroxide or a topical antibiotic), it should be applied in the evening and the other treatment in the morning. This is to minimise the risk of photosensitivity, and because benzoyl peroxide inactivates tretinoin (but not adapalene). The fixed combination product Epiduo (adapalene 0.1% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5%) should be applied in the evening.

Azelaic acid is a dicarboxylic acid that has antimicrobial and anticomedonal properties. It is less likely to cause irritation than the other agents and can therefore be a useful alternative if benzoyl peroxide and topical retinoids are not tolerated. It can cause hypopigmentation of darker skin.

Antibiotic treatment options include topical erythromycin, tetracycline and clindamycin, and oral tetracyclines and trimethoprim. Increasing concerns about bacterial resistance have prompted some experts to question the use of antibiotics in acne treatment2 .

A systematic review[7]

has shown there is no difference between tetracyclines in treating acne, and there is little justification for continuing to prescribe minocycline. Oxytetracycline (500mg twice a day) or lymecycline (150–300mg daily) should be used instead.

Oral erythromycin is not commonly used for acne because of the emergence of resistant strains of P. acnes and the high incidence of gastrointestinal side effects.

Ideally, antibiotic treatment should be discontinued after 12 weeks. Any subsequent course of antibiotics should be preceded by treatment with benzoyl peroxide for five to seven days to reduce the number of resistant organisms on the skin[8]

.

Antibiotics should be combined with topical retinoids to enhance their effectiveness against comedones and inflammatory lesions.

Oral isotretinoin is indicated for the treatment of severe nodular acne and for moderate or severe acne that is unresponsive to other treatments. Many patients require only a single course of treatment (0.5–1mg/kg/day) for four to six months6 . The effects of treatment appear to persist for one or two months after discontinuation.

The most commonly reported side effects of isotretinoin are dryness of the skin and dryness of the mucosae, including the lips, nasal mucosa and eyes. Decreased night vision sometimes occurs during treatment and can affect patients’ driving ability at night[9]

.

Isotretinoin is teratogenic and can only be supplied to women who are prepared to sign up to a pregnancy prevention programme[10]

. The basic components of the scheme are:

- Educational material for patients

- Supervised pregnancy testing before, during and five weeks after the end of treatment

- Use of at least one method of contraception, and preferably two complementary forms of contraception including a barrier method, for at least one month before starting therapy. This should be continued throughout treatment and for at least one month after stopping therapy.

Isotretinoin prescriptions for women of childbearing age should be limited to 30 days, and dispensing should occur within a maximum of seven days of the prescription being issued. Ideally, pregnancy testing, prescribing and dispensing should occur on the same day.

Isotretinoin is present in semen, and it is a sensible precaution for men taking the medicine to use a condom. However, to date there have been no cases of adverse effects in pregnancy if a man taking isotretinoin fathers a child[11]

.

All patients taking isotretinoin should not give blood during and for one month after stopping therapy, due to the potential risk to the fetus of a pregnant transfusion recipient.

There are reports of mood changes and depression occurring in patients taking isotretinoin. However, a causal link remains unproven2 .

Acne itself can be a contributory factor in anxiety, depression and suicide. The British Association of Dermatologists recommends that a direct enquiry about previous mental health should be made when isotretinoin is being considered, and the details of this conversation recorded in the notes[12]

.

In addition, all patients — and their parents in the case of children and adolescents — should be made aware of the potential for mood change in a realistic, non-judgmental way, and advised to ask their family and friends to comment if they notice such changes. A direct enquiry about psychological symptoms should be made at each clinic visit.

If symptoms of depression or mood change do occur, then ideally isotretinoin should be discontinued. However, some patients, after discussion, may wish to continue with the drug because of the benefit to their skin. In such cases, specialist psychiatric support should be obtained.

Patients taking isotretinoin should not use other retinoids or supplements containing vitamin A because of the risk of toxicity.

Patients should return any unused isotretinoin capsules to the pharmacist for safe disposal.

Hormonal therapies may be useful for women with moderate or severe acne who have failed to respond to other treatments. They can also be useful for women with acne who require oral contraception or period regulation.

Progestogen-only oral contraceptives often worsen acne and should not be used.

Light treatment , including infrared lasers, pulsed dye lasers and intense pulsed light, have all been used in the treatment of acne. Reviews show that light treatments can improve inflammatory acne in the short term but the long-term effects are as yet unknown2 . Pain, redness, swelling and increased pigmentation are common side effects.

Referral

Pharmacists should refer a patient to their GP if they have numerous inflamed spots, obviously deep lesions or evidence of scarring, or are overly anxious about their spots. Patients who have used benzoyl peroxide correctly for six weeks and seen no effect should also be referred.

Supporting patients with acne

- Be supportive, not dismissive — ongoing patient education, follow-up, encouragement and maintaining a positive approach are vital

- Reassure patients that acne is not caused by poor hygiene, diet or infection

- When assessing acne, ask about the back and chest — patients, particularly teenage boys, can be reluctant to discuss the full extent of their acne

- Advise that gentle washing with mild products is needed. Soap and abrasives can be too drying and cause further damage

- Advise on suitable OTC benzoyl peroxide products — gels are good for greasy skin, creams for normal skin

- Explain that applying topical treatments will not “spread” acne to other areas of skin

- Moisturisers are often required because of the drying effects of some treatments — non-comedogenic products should be recommended

- Reassure patients that they can still use make-up; non-comedogenic products are ideal

- Manage expectations — patients who expect an instant response could be disappointed and may stop using treatment. A 50% improvement in two months is a realistic expectation

- Acne treatment can be long-term and require bouts of intensive treatment separated by maintenance treatment for many months or years

- Encourage effective use of medicines and encourage patients to feed back on progress

- Remember that patient perception of improvement is the best measure of successful treatment

References

[1]Purdy S & deBerker D. Acne. The BMJ 2006;333:949–53.

[2]Williams HC, Dellavelle RP & Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet 2012;379:361–72.

[6]Dawson AL & Dellavelle RP. Acne vulgaris. BMJ 2013;346:f2634.

[8] Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al . Management of acne: a report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;49:S1–S37.

[9]European Medicines Compendium. Isotretinoin [online]. Available from: www.medicines.org.uk.